Coverage and Use of Fertility Services in the U.S.

|

Key Takeaways

|

|

Introduction

Many people require fertility assistance to have children. This could either be due to a diagnosis of infertility, or because they are in a same-sex relationship or single and desire children. While there are several forms of fertility assistance, many services are out of reach for most people because of cost. Fertility treatments are expensive and often are not covered by insurance. While some private insurance plans cover diagnostic services, there is very little coverage for treatment services such as IUI and IVF, which are more expensive. Most people who use fertility services must pay out of pocket, with costs often reaching thousands of dollars. Very few states require private insurance plans to cover infertility services and only one state requires coverage under Medicaid, the health coverage program for low-income people. This widens the gap for low-income people, even when they have health coverage. This brief examines how access to fertility services, both diagnostic and treatment, varies across the U.S., based on state regulations, insurance type, income level and patient demographics.

Diagnosis and Treatment Services

Infertility is most commonly defined1 as the inability to achieve pregnancy after 1 year of regular, unprotected heterosexual intercourse, and affects an estimated 10-15% of heterosexual couples. Both female and male factors contribute to infertility, including problems with ovulation (when the ovary releases an egg), structural problems with the uterus or fallopian tubes, problems with sperm quality or motility, and hormonal factors (Figure 1). About 25% of the time, infertility is caused by more than one factor, and in about 10% of cases infertility is unexplained. Infertility estimates, however do not account for LGBTQ or single individuals who may also need fertility assistance for family building. Therefore, there are varied reasons that may prompt individuals to seek fertility care.

A broad array of diagnostic and treatment services may be necessary to assist in fertility (Table 1). Diagnostics typically include lab tests, a semen analysis and imaging studies or procedures of the reproductive organs. If a probable cause of infertility is identified, treatment is often directed at addressing the source of the problem. For example, if someone has abnormal thyroid hormone levels, thyroid medications may help the patient achieve pregnancy. If a patient has large fibroids distorting the uterine cavity, surgical removal of these benign tumors may allow for future pregnancy. Other times, other interventions are needed to help the patient achieve pregnancy. For example, if a semen analysis reveals poor sperm motility or the fallopian tubes are blocked, the sperm will not be able to fertilize the egg, and intrauterine insemination (IUI) or in-vitro fertilization (IVF) may be necessary. These procedures also facilitate family building for LGBTQ and single individuals, with use of donor egg or sperm, with or without a gestational carrier (surrogacy).

| Table 1: Overview of Common Fertility Services | |

| Diagnostic Services: |

|

| Treatment Services: |

|

| Fertility Preservation: |

|

| NOTES: This is not an exhaustive list of infertility services. SOURCE: ACOG. Evaluating Infertility. 2017; ACOG. Treating Infertility. 2019; American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Infertility: An Overview. Patient Information Series. 2017 |

|

Utilization of Fertility Services

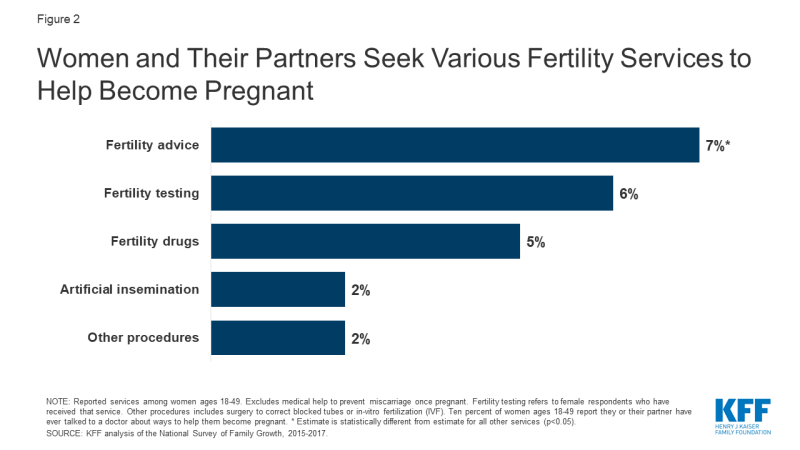

Our analysis of the 2015-2017 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) finds that 10% of women2 ages 18-49 say they or their partner have ever talked to a doctor about ways to help them become pregnant (data not shown).3 Among women ages 18-49, the most commonly reported service is fertility advice (Figure 2).

The CDC finds that use of IVF has steadily increased since its first successful birth in 1981. According to the most recent data, an estimated 1.8% of U.S. infants are conceived annually using assisted reproductive technology (ART) (e.g., IVF and related procedures).4 The proportions are highest in the Northeast (MA 4.7%, CN 3.9%, NJ 3.9%), and lower in the South and Southwest (NM 0.4%, AR 0.6%, MS 0.6%).

Utilization of fertility services has dropped drastically during the COVID-19 public health emergency. On March 17, 2020 the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) issued guidelines to stop all new fertility treatment cycles and non-urgent diagnostic procedures. Since then, ASRM has provided updated guidance on what conditions should be met and measures should be taken before safely resuming fertility care. During this time, a study by Strata Decision Technology of 228 hospitals across 40 states found patient encounters for infertility services were down 83% from March 22 to April 4, 2020 compared to this time the year prior.

Cost of Services

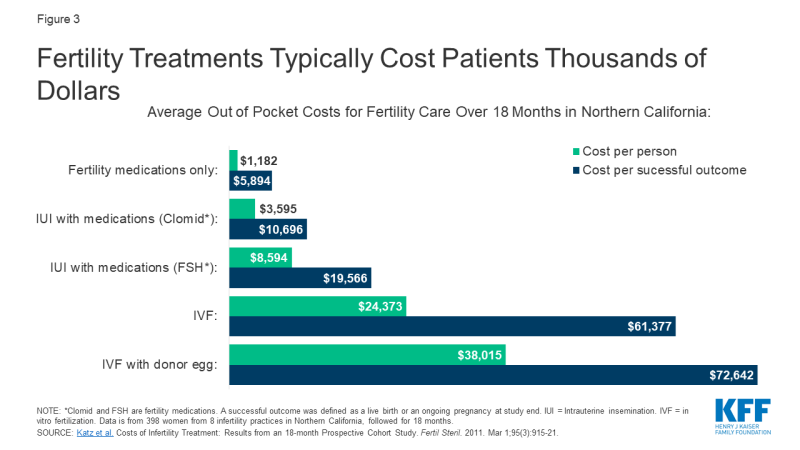

Many patients lack access to fertility services, largely due to its high cost and limited coverage by private insurance and Medicaid. As a result, many people who use fertility services must pay out of pocket, even if they are otherwise insured. Out of pocket costs vary widely depending on the patient, state of residence, provider and insurance plan. Generally, diagnostic lab tests, semen analysis and ultrasounds are less expensive than diagnostic procedures (e.g., HSG) or surgery (e.g., hysteroscopy, laparoscopy). Meanwhile treatment using fertility medications is less expensive than IUI and IVF, but even the less costly treatments can still result in thousands of dollars of out of pocket costs. Many people must try multiple treatments before they or their partner can achieve a pregnancy (typically medication first, followed by surgery or fertility procedures if medications are unsuccessful). A study of nearly 400 women undergoing fertility care in Northern California demonstrates this overall trend, with the lowest out of pocket spending on treatment with medication only and the highest costs for IVF services (Figure 3). Prior research showed the cost of just one standard cycle of IVF was approximately $12,500 in 2009, but is likely higher today due to rising health care costs overall. Furthermore, many patients require several rounds of treatment before achieving a pregnancy, with costs accruing each cycle making these interventions financially inaccessible for many. In addition to costs for the actual treatment, patients can be saddled with out of pocket expenses for office visits, diagnostic tests/procedures, genetic testing, donor sperm/egg use and storage fees and wages lost from time off work.

Insurance Coverage

Insurance coverage of fertility services varies by the state in which the person lives and, for people with employer-sponsored insurance, the size of their employer. Many fertility treatments are not considered “medically necessary” by insurance companies, so they are not typically covered by private insurance plans or Medicaid programs. When coverage is available, certain types of fertility services (e.g., testing) are more likely to be covered than others (e.g., IVF). A handful of states require coverage of fertility services for some fully-insured private plans, which are regulated by the state. These requirements, however, do not apply to health plans that are administered and funded directly by employers (self-funded plans) which cover six in ten (61%) workers with employer-sponsored health insurance. States also have purview over the benefits covered by their Medicaid programs. The federal government has authority over benefit requirements in federal health coverage programs, including Medicare, the Indian Health Service (IHS) and military health coverage.

Private Insurance

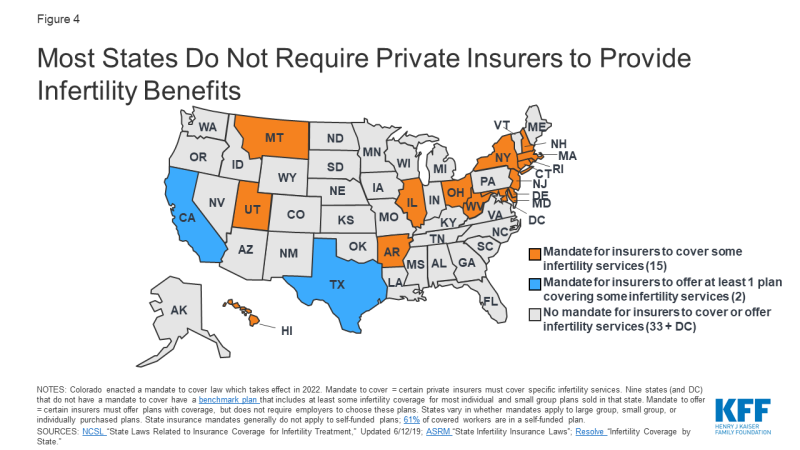

Fifteen states have laws in effect requiring certain health plans to cover at least some infertility treatments (a “mandate to cover”) (Figure 4). Additionally, Colorado recently enacted a requirement for individual and group health benefit plans to cover infertility diagnosis, treatment and fertility preservation for iatrogenic infertility, effective January 2022. Among states that do not have a mandate to cover, nine states5 and DC have a benchmark plan that includes coverage for at least some infertility services (diagnosis and/or treatment) for most individual and small group plans sold in that state.6 Two states (CA and TX7) require group health plans to offer at least one policy with infertility coverage (a “mandate to offer”), but employers are not required to choose these plans.

However, in states with “mandate to cover” laws, these only apply to certain insurers, for certain treatment services and for certain patients, and in some states have monetary caps on costs they must cover (Appendix 1). For example, in OH and WV, the requirement to cover infertility services only applies to health maintenance organizations (HMOs). In other states, almost all insurers and HMOs are included in the mandate. Many states provide exemptions for small employers (<50 employees) or religious employers. In addition, state laws do not apply to self-funded (or self-insured) employer plans, which are regulated by federal law. Sixty-one percent of covered workers are enrolled in a self-funded plan.

Even in states with coverage laws, not all patients are eligible for infertility treatment. In HI, someone with unexplained infertility only qualifies for IVF after five years of infertility. In others, patients are eligible after 1 year. Some states place age limits on female patients who can access these services (e.g., ineligible if 46 or older in NJ or if under age 25 or older than 42 in RI). Others place restrictions based on marital status; for example, until May 2020, IVF benefits were only available to married women in MD. Recently enacted legislation now expands coverage to unmarried women. Additionally, it is not always made clear if LGBTQ individuals meet eligibility criteria for these benefits, without a diagnosis of infertility. Furthermore, many costs associated with surrogacy are often not covered by insurance.

States also vary in which treatment services they require plans to cover. Some states mandate insurers to cover cryopreservation for persons with iatrogenic infertility, while others do not. Four states with insurer mandates do not cover IVF. Eleven states do, but with a dollar limit on coverage (e.g., $15,000 lifetime max in AR and $100,000 in MD and RI) or a limit on the number of cycles they will cover (e.g., one cycle of IVF in HI and three cycles in NY).

Do state mandates for IVF coverage affect use of services?

IVF utilization appears to be higher in states with mandated IVF coverage. CDC data from 2016 showed that in three of the four states deemed by the CDC to have “comprehensive coverage”8 for IVF (IL, MA, NH), use of assisted reproductive technology was 1.5 times higher than the national rate. Similarly, a national study found that IVF availability and utilization9 were significantly higher in states with mandated IVF coverage. A study in MA found IVF utilization increased after implementation of their IVF mandate, but overutilization by patients with a low chance of pregnancy success was not found. State level mandates can also help reduce inequities in access. For example, a recent bill proposed in the CA legislature would reverse existing limitations on fertility coverage and make the benefit available to single women and women in same sex relationships.

What does it cost to cover fertility benefits?

While the costs of fertility treatments can be very expensive for those who lack coverage, the cost of covering fertility benefits varies depending on the services covered and utilization with implications for state budgets, employers, and policy holders. For example, in 2019, New York passed a bill to require IVF and fertility preservation services for comprehensive private health insurance policies. The New York State Department of Financial Services estimated that premiums would increase 0.5% to 1.1% due to mandating IVF coverage, and 0.02% for mandating fertility preservation for iatrogenic infertility (caused by medical treatments).

An analysis of a bill proposed in CA to require private plans and Medi-Cal managed care plans to cover IVF services estimated that per member per month premiums would increase by approximately $5 in the private market and less than a $1.00 for Medi-Cal plans. Overall though, out of pocket spending for individuals seeking services would decrease substantially.

Data from MA, CT and RI suggest that mandating coverage does not appear to raise premiums significantly. All three states have been mandating infertility benefits for over 30 years, and estimate the cost of infertility coverage to be less than 1% of total premium costs. In 2017, California was considering a more limited bill that would require fertility preservation for iatrogenic infertility in certain individual and group health plans. As the bill was introduced, it was estimated to result in a net annual increase of $2,197,000 in premium costs or 0.0015% for enrollees in plans subject to the mandate.

While these costs could be modest in comparison to the costs of paying out-of-pocket for these services, there are other costs to coverage mandates. The ACA requires states to offset some of the costs for any state mandated benefits beyond essential health benefits (EHBs) in the individual and small group market. This requirement was estimated to cost NY $59 to $69 million per year if covering one cycle or $98 to $116 million per year if covering unlimited cycles of IVF.

What share of employers offer fertility benefits?

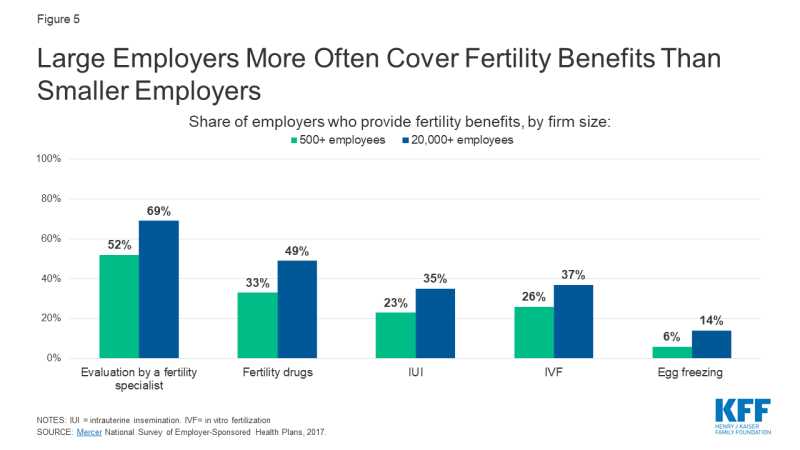

Large employers are more likely than smaller employers to include fertility benefits in their employer-sponsored health plans. According to Mercer’s 2017 National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Plans, 56% of employers with 500 or more employees cover some type of fertility service, but most do not cover treatment services such as IVF, IUI, or egg freezing. Coverage is higher for diagnostic evaluations and fertility drugs. Coverage is more common among the largest employers and those that offer higher wages (Figure 5).

Public Coverage

Medicaid

NSFG data show that significantly fewer women with Medicaid have ever used medical services to help become pregnant compared to women with private insurance. As of January 2020, our analysis of Medicaid policies and benefits reveal only one state, New York, specifically requires their Medicaid program to cover fertility treatment (limited to 3 cycles of fertility drugs) (Figure 6). However, some states may require Medicaid to cover treatments for conditions that impact fertility, while not directly stated in their policies. For example, states may cover thyroid medications, or cover surgery for fibroids, endometriosis or other gynecologic abnormalities if causing pelvic pain, abnormal bleeding or another medical problem, other than infertility. No state Medicaid program currently covers artificial insemination (IUI), IVF, or cryopreservation (Appendix 2).

Some states specifically cover infertility diagnostic services; GA, HI, MA, MI, MN, NH, NM and NY all offer at least one Medicaid plan with this benefit, but the range of diagnostics covered varies. For example, New York Medicaid specifically covers office visits, HSGs, pelvic ultrasounds and blood tests for infertility. Meanwhile, the infertility assessment covered by Georgia Medicaid includes lab testing, but not imaging or procedural diagnostics. Other states specifically do not cover infertility diagnostics, or more generally do not cover “infertility services,” which likely includes diagnostics. Others do not mention infertility diagnostics in their Medicaid policies, meaning the beneficiary would need to check with their Medicaid program to see if these services are covered (Appendix 2).

The Medicaid program’s lack of coverage of fertility assistance has a disproportionate impact on women of color. Among reproductive age women, the program covers three in ten (30%) who are Black and one quarter who are Hispanic (26%), compared to 15% who are White. Because eligibility for Medicaid is based on being low-income, people enrolled in the program likely could not afford to pay for services out of pocket.

The relative lack of Medicaid coverage for fertility services stands in stark contrast to Medicaid coverage for maternity care and family planning services. Nearly half of births in the U.S. are financed by Medicaid, and the program finances the majority of publicly-funded family planning services. Therefore, while there is broad coverage of many services for low-income people during pregnancy and to help prevent pregnancy, there is almost no access to help low-income people achieve pregnancy.

Medicare

While most beneficiaries of Medicare are over the age of 65+, Medicare also provides health insurance to approximately 2.5 million reproductive age adults with permanent disabilities. According to the Medicare Benefit policy manual, “reasonable and necessary services associated with treatment for infertility are covered under Medicare.” However, specific covered services are not listed, and the definition of “reasonable and necessary” are not defined.

Military

TRICARE: TRICARE, the insurance program for military families, will cover some infertility services, if deemed “medically necessary” and if pregnancy is achieved through “natural conception,” meaning fertilization occurs through heterosexual intercourse. Diagnostic services are covered, including lab testing, genetic testing, and semen analysis. Treatment to correct physical causes of infertility are also covered. However, IUI, IVF, donor eggs/sperm and cryopreservation are not typically covered, unless the service member had a serious injury while on active duty resulting in infertility.

Veterans Affairs (VA): Infertility services are covered by the VA medical benefits package, if infertility resulted from a service-connected condition. This includes infertility counseling, blood tests, genetic counseling, semen analysis, ultrasound imaging, surgery, medications and IVF (as of 2017). However, the couple seeking services must be legally married, and the egg and sperm must come from said couple (effectively excluding same sex couples). Donor eggs/sperm, surrogacy or obstetrical care for non-Veteran spouses are not covered.

Infertility Services In Publicly Funded Clinics

The CDC’s and Office of Population Affairs’ (OPA) Quality Family Planning recommendations address provision of basic infertility services. Family planning providers are recommended to provide at minimum patient education about fertility and lifestyle modifications, a thorough medical history and physical exam, semen analysis, and if indicated, referrals for lab testing of hormone levels, additional diagnostic tests (endometrial biopsy, ultrasound, HSG, laparoscopy) and prescription of medications to promote fertility. However, studies of publicly funded family planning clinics suggest that availability of infertility services is uneven. In a 2013-2014 study of 1615 publicly funded clinics, a high share reported offering preconception care (94% for women and 69% for men), but fewer offered any basic infertility services (66% for women and 45% for men). Provision of any infertility treatment was uncommon (16% of clinics), likely requiring referrals to specialists who may not accept Medicaid or uninsured patients.10 The majority of patients who rely on publicly funded clinics are low-income and would not likely be able to afford infertility services and treatments once diagnosed.

Per the Indian Health Services (IHS) provider manual, basic infertility diagnostics should be made available to women and men at IHS facilities, including a history, physical exam, basal temperature charting (to predict ovulation), semen analysis and progesterone testing. In facilities with OBGYNs, HSG, endometrial biopsy and diagnostic laparoscopy should also be available. However, it is unclear how accessible these services are in practice, and provision of infertility treatment is not mentioned.

Key Populations

Racial and ethnic minorities

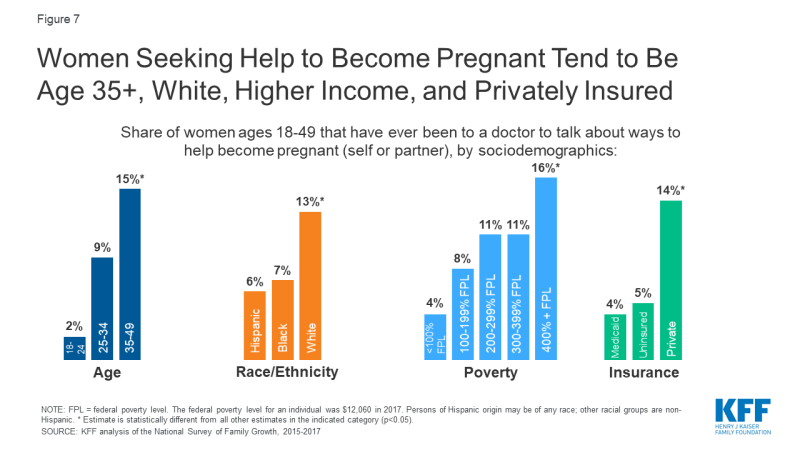

The ability to have and care for the family that you wish for is a fundamental tenet of reproductive justice. For those who need it, this includes access to fertility services. The share of racial and ethnic minorities who utilize medical services to help become pregnant is less than that of non-Hispanic White women, despite research that has found higher rates of infertility among women who are Black and American Indian / Alaska Native (AI/AN). Our analysis of 2015-2017 NSFG data shows that while 13% of non-Hispanic White women reported ever going to a medical provider for help getting pregnant, just 6% of Hispanic women and 7% of non-Hispanic Black women did so (Figure 7). A higher share of Black and Hispanic women are either covered by Medicaid or uninsured than White women and more women with private insurance sought fertility help than those with Medicaid or the uninsured. A variety of factors, including differences in coverage rates, availability of services, income, and service‐seeking behaviors, affect access to infertility care. Furthermore, other societal factors also play a role. Misconceptions and stereotypes about fertility have often portrayed Black women as not requiring fertility assistance. Combined with the history of discriminatory reproductive care and harm inflicted upon many women of color over decades, some may delay seeking infertility care or may not seek it at all.

Figure 7: Women Seeking Help to Become Pregnant Tend to Be Age 35+, White, Higher Income, and Privately Insured

Other research has found that use of fertility testing and treatment also varies by race. An analysis of NSFG data found that among women who reported using medical services to help become pregnant, similar shares of Black (69%), Hispanic (70%) and White (75%) women received fertility advice. However, less than half (47%) of Black and Hispanic women who used medical services to become pregnant reported receiving infertility testing, compared to 62% of White women, and even fewer women of color received treatment services. According to an analysis of surveillance data of IVF services, use is highest among Asian and White women and lowest among American Indian / Alaska Native (AI/AN) women. Racial inequities may exist for fertility preservation as well; a study of female patients in NY with cancer found disproportionately fewer Black and Hispanic patents utilized egg cryopreservation compared to White patients. On average, more Black, Hispanic, and AI/AN people live below the federal poverty level than people who are White or of Asian/Pacific Islander descent. The high cost and limited coverage of infertility services make this care inaccessible to many people of color who may desire fertility preservation, but are unable to afford it.

Iatrogenic Infertility

Iatrogenic, or medically induced, infertility refers to when a person becomes infertile due to a medical procedure done to treat another problem, most often chemotherapy or radiation for cancer. In these situations, persons of reproductive age may desire future fertility, and may opt to freeze their eggs or sperm (cryopreservation) for later use. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) encourages clinicians to inform patients about fertility preservation options prior to undergoing treatment likely to cause iatrogenic infertility.

However, the cost of egg or sperm retrieval and subsequent cryopreservation can be prohibitive, particularly if in the absence of insurance coverage. Only a handful of states (CT, DE, IL, MD, NH, NJ, NY, and RI) specifically require private insurers to cover fertility preservation in cases of iatrogenic infertility. No states currently require fertility preservation in their Medicaid plans.

LGBTQ populations

LGBTQ people may face heightened barriers to fertility care, and discrimination based on their gender identity or sexual orientation. Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) prohibits discrimination in the health care sector based on sex, but the Trump Administration has eliminated these protections through regulatory changes. Without the explicit protections that have been dropped in the current rules, LGBTQ patients may be denied health care, including fertility care, under religious freedom laws and proposed changes to the ACA. However, these changes are being challenged in the courts because they conflict with a recent Supreme Court decision stating that federal civil rights law prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

In a committee opinion, ASRM concluded it is the ethical duty of fertility programs to treat gay and lesbian couples and transgender persons, equally to heterosexual married couples. They write that assisted reproductive therapy should not be restricted based on sexual orientation or gender identity, and that fertility preservation should be offered to transgender people before gender transitions. This allows transgender individuals the ability to have biological children in the future if desired. Despite this recommendation, in aforementioned states with mandated fertility preservation coverage for iatrogenic infertility, it remains unclear if this benefit extends to transgender individuals, whose gender affirming care can result in infertility. Additionally, many state laws regarding mandates for infertility treatment contain stipulations that may exclude LGBTQ patients. For example, in Arkansas, Hawaii and Texas and at the VA, IVF services must use the couple’s own eggs and sperm (rather than a donor), effectively excluding same sex couples. In other states, same-sex couples do not meet the definition of infertility, and thus may not qualify for these services. Data are lacking to fully capture the share of LGBTQ individuals who may utilize fertility assistance services. Research studies on family building are often not designed to include LGBTQ respondents’ fertility needs.

Single Parents

Single persons are often excluded from access to infertility treatment. For example, the same IVF laws cited above that require the couple’s own sperm and egg, effectively exclude single individuals too, as they cannot use donors. Some grants and other financing options also stipulate funds must go towards a married couple, excluding single and unmarried individuals. This is in opposition to the ASRM committee opinion, which states that fertility programs should offer their services to single parents and unmarried couples, without discrimination based on marital status.

Looking Forward

On a federal level, efforts to pass legislation to require insurers to cover fertility services are largely stalled. The proposed Access to Infertility Treatment and Care Act (HR 2803 and S 1461), which would require all health plans offered on group and individual markets (including Medicaid, EHBP, TRICARE, VA) to provide infertility treatment, is still in committee (and never made it out of committee when proposed during the 115th congress). There has been some more movement on the state level. Some states require private insurers to cover infertility services, the most recent of which was NH in 2020. Currently, NY continues to be the first and only state Medicaid program to cover any fertility treatment.

For those who desire to have children, obtaining fertility care can be a stressful process. Stigma around infertility, intensive and sometimes long or painful treatment regimens, and uncertainty about success can take a toll. On top of that, in the absence of insurance coverage, infertility care is cost prohibitive for most, particularly for low-income people and for more expensive services, like IVF or fertility preservation. Significant disparities exist within access to infertility services across, dictated by state of residence, insurance plan, income level, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation and gender identity. Achieving greater equity in access to fertility care will likely depend on addressing the needs faced by low-income persons, people of color and LGBTQ persons in fertility policy and coverage.