Coronavirus Puts a Spotlight on Paid Leave Policies

Introduction

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other public health officials recommend that people who are sick with COVID-19 should stay home and that employers should consider implementing a telecommuting program when possible. Benefits such as sick leave and family leave can help employees follow these guidelines. However, the U.S. does not have national standards on paid family or sick leave. Our current system is a patchwork of policies that are determined by employers, state and local laws, or negotiated through labor contracts. Offer rates vary between employers, the reasons for needing leave, and the employment status of their workers. The lack of a national policy means some employees are forced to take unpaid leave, or come to work when they are ill. The lack of paid leave disproportionately impacts certain populations, including low-income persons, who are less likely to have access to these benefits, and could have public health consequences if people cannot afford to take time off. Lack of paid leave also has a large impact on women, who take on the bulk of health care responsibilities for their family members and may have to miss work as a result.

While there have been previous congressional efforts to create a uniform national floor for paid leave, this issue has gained new urgency with efforts to stem the spread of COVID-19. Since the outbreak began in the U.S., the President has signed into law the Families First Coronavirus Response Act as well as the C.A.R.E.S. Act. These laws include the following emergency short-term paid sick leave benefits and longer-term paid family leave policies.

- Employers with fewer than 500 employees and all public employers are required to provide up to two weeks of fully-paid sick leave (up to $5,110) for immediate use to workers unable to work due to their own quarantine or symptoms of coronavirus, and up to two-thirds of regular pay for two weeks (up to $2,000) for employees who are unable to work in order to care for someone in quarantine or whose child’s school or daycare is closed because of coronavirus.

- Separately, employers with fewer than 500 employees and all public employers are required to provide paid family leave to workers who are unable to work because their child’s school or daycare has closed due to coronavirus in the amount of two-thirds of their regular pay (up to $10,000) for up to 12 weeks, after a 10-day unpaid waiting period.

- The emergency paid family leave benefit only applies to employees covered by Title II of the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA); therefore, most federal employees are not eligible.

- Neither emergency paid leave provision applies to employees of private businesses with 500 or more employees.

- Health care workers, emergency responders, and certain federal employees in the Executive Branch may also be excluded from receiving these benefits.

- Workers employed by a business with fewer than 50 employees may also be excluded from receiving these benefits if their reason for missing work is due to their child’s school or daycare closure.

- Participating employers will receive advanceable quarterly tax credits to cover the costs of providing the new leave benefits.

- All provisions take effect 15 days after enactment (April 1, 2020), do not provide for retroactive benefits, and expire December 31, 2020.

Access to paid sick leave benefits varies greatly between employees, employers, and regions.

Sick leave benefits typically allow employees to miss work without losing pay when they or a family member has a short-term illness. There is no federal requirement that employers offer employees paid sick leave, but some employees, including federal government employees, have generally had access to paid sick leave through employee benefits packages.

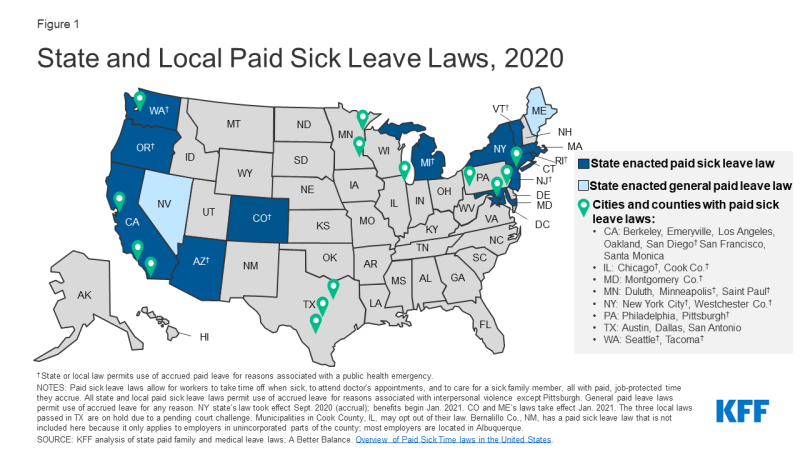

Thirteen states plus D.C. and 22 cities and counties1 have passed laws requiring that eligible employees get paid time off to care for themselves or sick family members. Another two states (ME and NV) require employers to provide general paid time off for workers to use as needed, including for sick leave (Figure 1). These state and local laws, however, do not apply to all workers in these locations; small employers are sometimes exempt, and part-time workers and those who have worked for their employers for a short duration may not be eligible for these benefits. Additionally, the duration, accrual rates, and circumstances under which paid sick leave may be taken vary by policy and state. Eight states’ and 11 localities’ requirements explicitly apply to public health emergencies, such as closure of a business or child’s school to protect public health.

In response to coronavirus, on March 17, 2020, New York state implemented a temporary emergency paid sick leave law for workers who are subject to coronavirus-related quarantine (or to care for their children subject to quarantine). Since then, another four states, plus D.C., and 14 localities2 have passed their own emergency paid sick leave laws, many aimed at closing the gaps in the federal FFCRA legislation.

Research suggests that paid sick leave can help stem the spread of illness by reducing presenteeism (going to work ill) in the workplace and the chance of sending sick children to school or daycare. Sick workers are more likely to stay home when they do not lose pay. Parents with paid sick leave benefits may be less likely to send sick children to school than parents without these benefits.

How many workers have paid sick leave?

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, three in four (75%) of workers in private industry have access to at least some paid sick leave, as do approximately nine in ten (91%) state and local government workers.

However, there are wide disparities in access to paid sick leave (Table 1). Among private industry workers, rates of paid sick leave rise with wages, with about half (49%) of workers in the lowest wage quartile ($13.25/hour on average) having this benefit, compared to 92% in the highest quartile. Less than half of part-time workers (45%) in private industry have paid sick leave, compared to 86% of full-time employees. The lower likelihood of paid sick leave for part-time workers has a disproportionate impact on women, who are more likely than men to hold part-time jobs. Workers in certain industries are more likely to have paid sick leave than in others. Union workers (88%) and workers are larger employers (88%) are more likely than non-union workers (74%) and workers at smaller employers (66%) to offer paid sick leave to their workers. Access to paid sick leave also varies by worker occupation. For example, 95% of workers in management, business, and financial occupations have paid sick leave, compared to 57% of workers in construction, extraction, farming, fishing, and forestry occupations.

Among workers in private industry who have paid leave benefits, the average duration is seven days; however, one-quarter (25%) of workers have fewer than five days. For state and local government workers, the average is 11 days, and 9% have fewer than five days.

| Table 1. Share of Private Industry and Government Workers with Access to Paid Sick Leave, 2020 | ||

| Private Industry | State/Local Govt. | |

| All Workers | 75% | 91% |

| Full-Time | 86% | 99% |

| Part-Time | 45% | 46% |

| Union | 88% | 98% |

| Non-Union | 74% | 86% |

| Average Wage: | ||

| Lowest 25% | 49% | 79% |

| Second 25% | 80% | 96% |

| Third 25% | 87% | 97% |

| Highest 25% | 92% | 96% |

| Employer Size: | ||

| <50 workers | 66% | 86% |

| 50-99 workers | 74% | 93% |

| 100-499 workers | 82% | 90% |

| 500+ workers | 88% | 93% |

| Worker Occupations: | ||

| Management, business, and financial | 95% | – |

| Teachers | – | 93% |

| Service | 59% | 85% |

| Sales and related | 65% | – |

| Office and administrative support | 84% | 93% |

| Construction, extraction, farming, fishing, and forestry | 57% | – |

| Installation, maintenance, and repair | 79% | – |

| Production, transportation, and material moving | 72% | 90% |

|

NOTE: Dash indicates no workers in this category or data did not meet publication criteria. Ninety-four percent of registered nurses in the civilian workforce (private industry and state and local government) have access to paid sick leave. SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation Survey, March 2020. Table 6. Selected paid leave benefits: Access.

|

||

Most workers do not have paid family and medical leave benefits.

Should the coronavirus require employees to stay home from work for longer periods, some may turn to family and medical leave benefits, which typically can be used for longer-term illnesses. This is particularly important for COVID-19, given that some infected persons could be quarantined for as long as 14 days.

There is no federal requirement for employers to provide paid family and medical leave. The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) requires eligible employers to provide 12 weeks of unpaid family leave to care for seriously ill family members, and job protection when employees return to work. Employees can use family leave to care for children or other relatives, including aging parents, who are at heightened risk for coronavirus. Women are the primary caregivers for the nation’s older population, comprising roughly two-thirds of informal caregivers, and many work outside the home.

The FMLA protections apply to 60% of the workforce, as the law only applies to employers with at least 50 employees, and not all employees within covered worksites are eligible. This means that in addition to losing pay when they take medical leave, many workers’ jobs may not be protected by the FMLA.

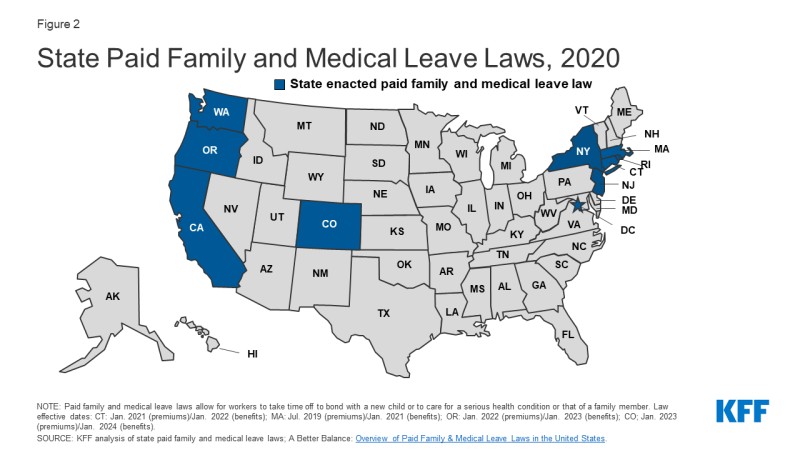

Currently, nine states and D.C. have enacted paid family leave laws, with partial wage replacement up to a designated cap (Figure 2). Duration of leave varies by state, but most provide for 6 to 12 weeks, and all allow leave for the care of seriously ill children, spouses, partners, parents, and in some cases to all blood relatives. Some of these state policies use disability benefits systems to provide the wage replacement.

How many workers have paid family and medical leave?

Despite strong public support and the growing interest in paid family and medical leave at the local level, only 20% of private industry workers and 26% of state and local government workers have access to it, with wide variation around worker and employer characteristics (Table 2). As with access to paid sick leave, full-time workers, higher-wage earners, workers at larger employers, and management/professional occupations are more likely to have access to paid family leave than their counterparts.

| Table 2. Share of Private Industry and Government Workers with Access to Paid Family Leave, 2020 | ||

| Private Industry | State/Local Govt. | |

| All Workers | 20% | 26% |

| Full-Time | 24% | 28% |

| Part-Time | 8% | 12% |

| Union | 18% | 28% |

| Non-Union | 20% | 23% |

| Average Wage: | ||

| Lowest 25% | 8% | 21% |

| Second 25% | 19% | 26% |

| Third 25% | 23% | 25% |

| Highest 25% | 33% | 29% |

| Employer Size: | ||

| 1-49 workers | 13% | 26% |

| 50-99 workers | 19% | 19% |

| 100-499 workers | 22% | 29% |

| 500+ workers | 31% | 24% |

| Worker Occupations: | ||

| Management, professional, and related | 33% | 27% |

| Teachers | – | 28% |

| Service | 12% | 23% |

| Sales and office | 21% | 24% |

| Natural resources, construction, and maintenance | 13% | 27% |

| Production, transportation, and material moving | 11% | 22% |

|

NOTE: Dash indicates no workers in this category or data did not meet publication criteria. Thirty-six percent of registered nurses in the civilian workforce (private industry and state and local government) have access to paid sick leave. SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation Survey, March 2020. Excel dataset.

|

||

Few low-wage workers have worked at home.

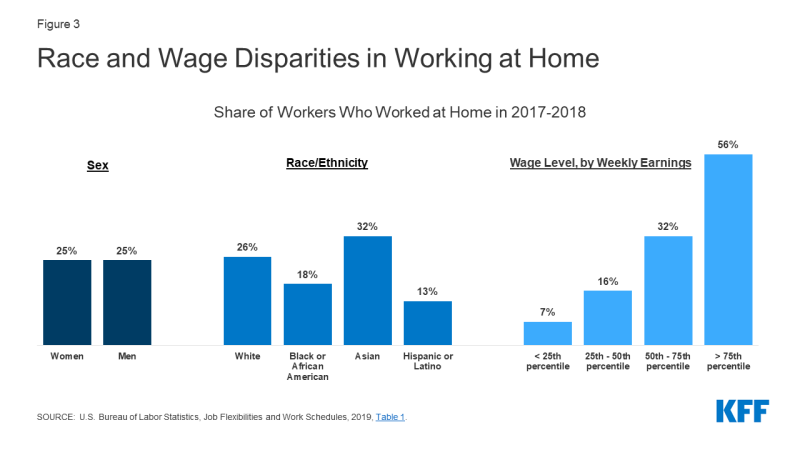

The CDC has also encouraged employers to consider greater use of telecommuting as part of the push for social distancing during the pandemic. However, not all employers or job positions are amenable to telecommuting. Just a quarter (25%) of workers worked at home in 2017-2018. The rate of telecommuting varies greatly between industries, with almost half of workers in financial activities and professional services (47%) having worked at home, compared to less than a tenth of workers in leisure and hospitality industries (7%). Within industries, there can be variation by position. Half (51%) of those in management positions have worked at home, compared to 7% in maintenance and repair positions. The share is also lower among workers with lower wages as well as Hispanic workers (Figure 3).

Among workers with children, mothers are usually the ones to stay home when children are sick. Most do not get paid during this time.

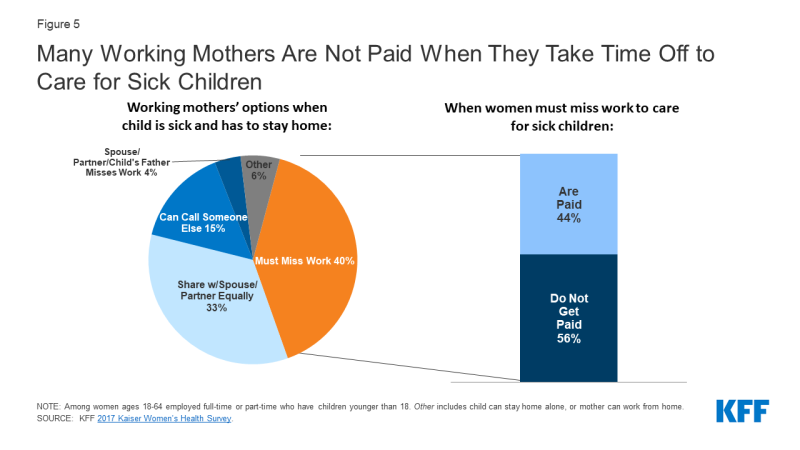

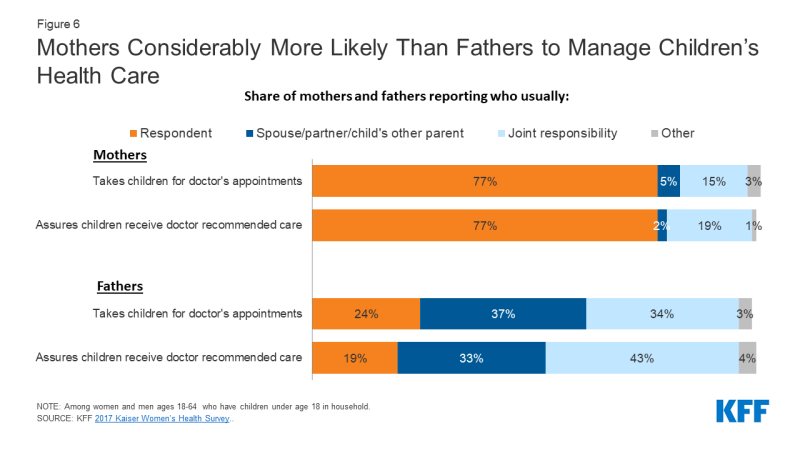

The limits on paid leave benefits are also of importance to parents who work outside the home, as some schools across the country have closed and many others are considering it in response to COVID-19. Women comprise nearly half of the nation’s workforce and are usually the ones to care for children when they are sick and cannot attend school or daycare. Four in ten (40%) mothers working outside the home say they must take time off work and stay home when their children are sick, compared to 10% of fathers working outside the home (Figure 4). However, more than half (56%) of the working mothers who must miss work when their children are sick forgo their wages when they take time off (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Among Parents in the Workplace, Mothers More Likely than Fathers to Stay Home with Sick Children

Having to miss work to care for a sick child has a disproportionate impact on workers who are low-income or in part-time jobs, as they are less likely than their counterparts to have paid sick leave or family leave benefits (Table 3). Furthermore, mothers in part-time jobs are more likely to report they have to miss work when their child is sick (51%) compared to about a third (36%) of their full-time counterparts. Low-income mothers who must miss work when their child is sick are also far more likely to lose pay (73%) compared to higher-income mothers (47%).

| Table 3. Paid Leave Among Working Mothers, 2017 | ||||

| Does your employer offer you: | When your child is sick do you: | |||

| Paid sick leave | Paid family leave | Have to miss work | Lose pay when you miss work | |

| Mothers <200% FPL | 56%* | 40%* | 43% | 73%* |

| Mothers ≥200% FPL | 70% | 54% | 38% | 47% |

| Mothers Full-Time Employment | 76% | 58% | 36% | 49% |

| Mothers Part-Time Employment | 34%* | 22%* | 51%* | n/a |

| NOTES: Among women ages 18-64 who have children under 18. The Federal Poverty Level (FPL) was $20,420 for a family of three in 2017. Some estimates are “n/a” because point estimates do not meet the minimum standards for statistical reliability. *Statistically significant difference from >200% FPL or Full Time (p<.05). SOURCE: KFF, 2017 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey. |

||||

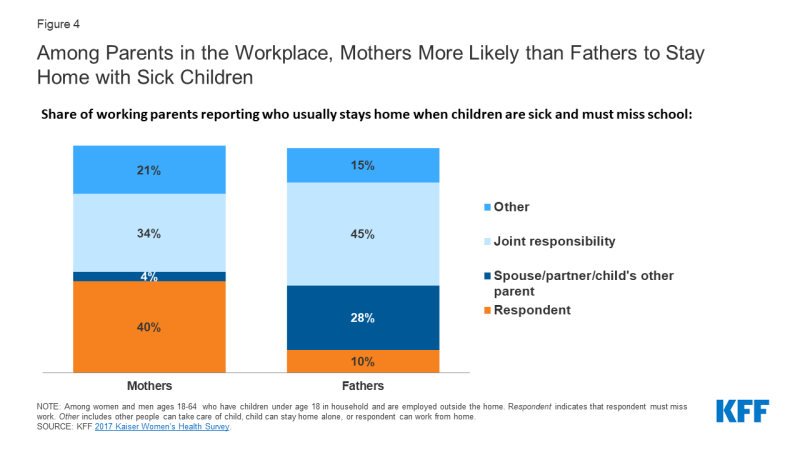

Should children become sick with COVID-19, lack of paid leave will also have a disproportionate impact on the nation’s mothers, who, more often than fathers, report being the primary person to take children for doctor’s appointments (77% mothers, 24% fathers) or obtain any recommended follow up care (77% mothers, 19% fathers) (Figure 6). Women also comprise the majority of caregivers for aging and sick parents.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic is shining a spotlight on gaps in employer leave benefits and the risk of employees losing pay if they stay home because they are sick or to care for others. Some employers have changed policies in light of this situation and are now offering more workers paid leave, which may encourage employees to stay home if they are sick and reduce risks to public health. Some employers say that they do not have the means to offer paid leave to their employees. While this pandemic adds new urgency to this issue, it is important to recognize that nearly all workers will need to take time off at some point during the course of their careers either for their own health or to care for a family member. However, those who earn the lowest wages are the least likely to have this important benefit. These individuals had a gap in benefits before the COVID-19 pandemic, and unless long term action is taken, will likely continue to lack paid leave after the urgency of the pandemic is behind us.

Endnotes

- Bernalillo Co., NM, has a paid sick leave law that is not included here because it only applies to employers in unincorporated parts of the county; most employers are located in Albuquerque.

- San Mateo and Sonoma Counties (CA) have temporary emergency paid sick leave laws that are not included here because they only apply to certain employers in unincorporated parts of the county.