Characteristics of Remaining Uninsured Men and Potential Strategies to Reach and Enroll them in Health Coverage

Summary

This brief provides information on remaining nonelderly uninsured men ages 19-64, provides national estimates of their eligibility for ACA coverage options, and discusses strategies for reaching and enrolling them into health coverage. Data and figures presented in this brief are based on Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2015 Current Population Survey data for nonelderly adults.1 Key findings include:

- In 2014, nearly 15 million nonelderly adult men were uninsured, accounting for slightly more than half of remaining uninsured adults. Men are more likely to be uninsured than women and less likely to have Medicaid or other public coverage. This pattern reflects the fact that many men were not eligible for Medicaid prior to the ACA, since the program excluded non-disabled adults without dependent children. Nonelderly uninsured men include many young childless adults, but also include fathers and older men. Most (76%) nonelderly uninsured men live in a household with at least one full-time worker, but more than half are low-income. Nearly one-third (32%) of nonelderly uninsured men reported having trouble paying medical bills in 2014.

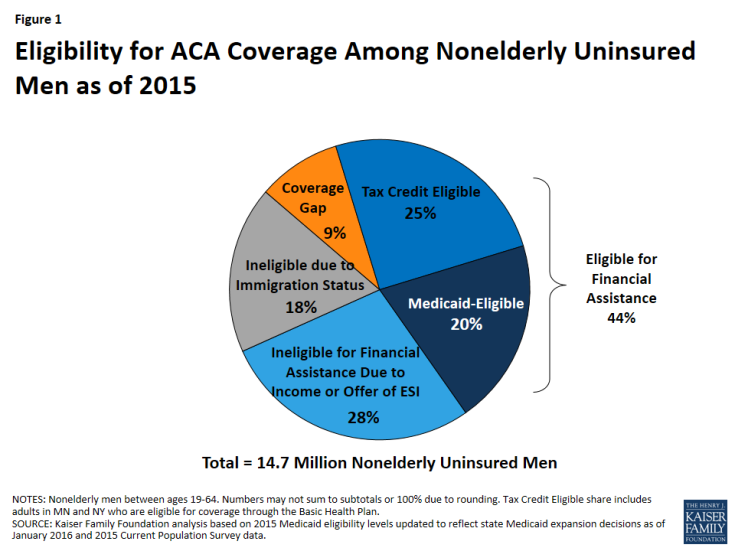

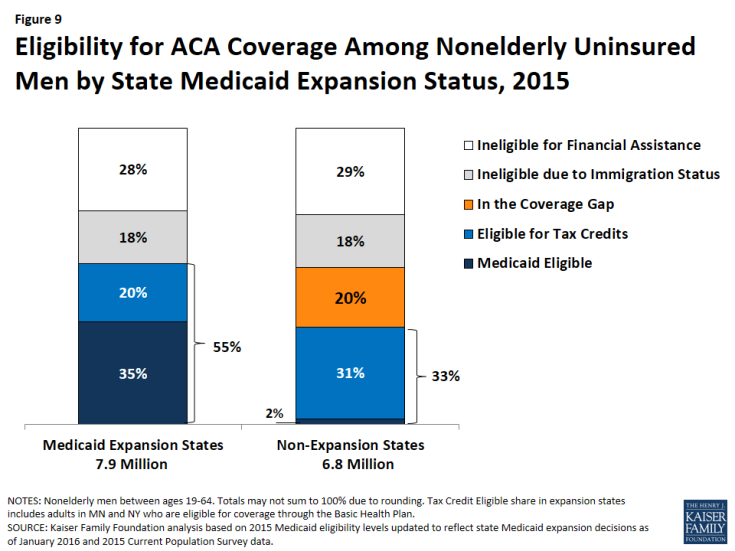

- Nationally, an estimated 44% of nonelderly uninsured men are eligible for financial assistance under the ACA (Figure 1). In Medicaid expansion states, over half (55%) of men are eligible for assistance, including over one-third (35%) who are eligible for Medicaid. In contrast, in non-expansion states, one-third (33%) are eligible for assistance, including just 2% who are eligible for Medicaid, while one in five (20%) falls into the coverage gap.

- Enrolling eligible uninsured men will be key for continued coverage gains. To reach and enroll uninsured men, longstanding outreach and enrollment strategies used to connect with families will be important, as well as targeted strategies for men, including specific strategies focused on reaching low-income fathers.

Introduction

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) extends health insurance coverage to people who lack access to an affordable coverage option. Under the ACA, as of 2014, Medicaid coverage is extended to low-income adults in states that have opted to expand eligibility, and tax credits are available for middle-income people who purchase coverage through a health insurance Marketplace. Although the number of uninsured adults ages 19-64 declined significantly in 2014, there were still over 27 million uninsured nonelderly adults in the U.S. at the start of 2015 based on analysis of 2015 Current Population Survey data.2 Over half of these adults, or nearly 15 million, were nonelderly uninsured men. This brief provides information on remaining nonelderly uninsured men, describing the characteristics of this population, explaining the importance of health coverage for them, providing national estimates of eligibility for ACA coverage options among this group, and discussing strategies for reaching and enrolling nonelderly uninsured men in health coverage.

How many nonelderly men are uninsured?

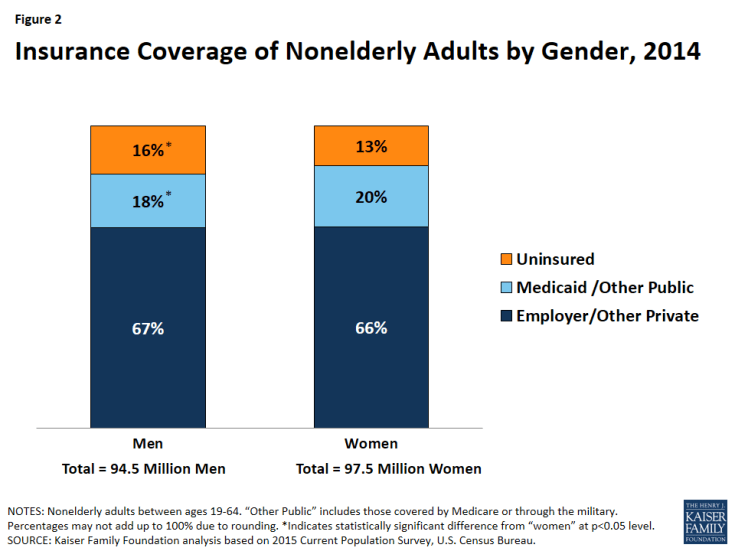

In 2014, nearly 15 million men ages 19-64 were uninsured in the U.S. There were a total of nearly 95 million nonelderly men in the U.S. in 2014. Of these men, 67% were covered by employer-based or other private coverage, 18% were covered by Medicaid or other public coverage, while 16% remained uninsured (Figure 2). Compared to women, men are less likely to have Medicaid or other public coverage and more likely to be uninsured. This coverage pattern reflects the fact that, prior to the ACA Medicaid expansion, the program played a very limited role for men since non-disabled adults without dependent children were not eligible.

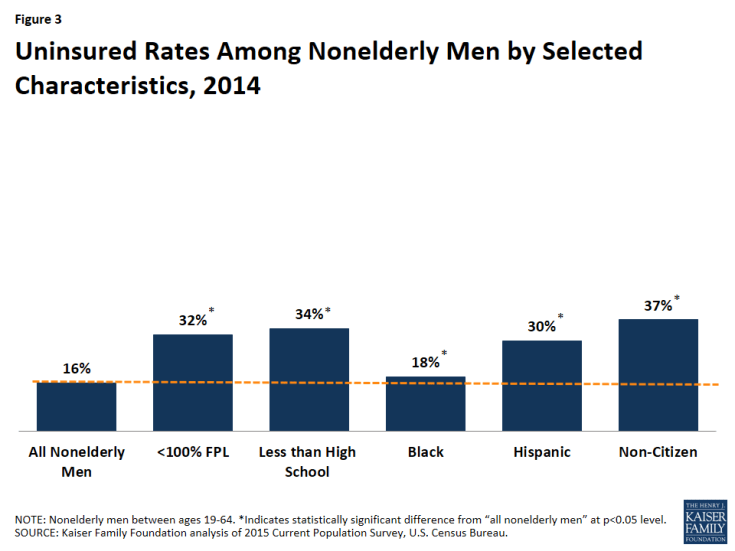

Uninsured rates for men vary widely across states and by certain characteristics. A man’s likelihood of being uninsured varies based on where he lives. Across states, the uninsured rate for men ranged from a high of 25% in Texas to a low of 6% in Massachusetts.3 Uninsured rates also vary by certain characteristics. For example, men with family income below 100% of the federal poverty level, men with less than a high school education, Black men, Hispanic men, and non-citizen immigrant men are at greater risk of being uninsured compared to the national average (Figure 3). In contrast, the uninsured rate for White men was 11%.

Who are nonelderly uninsured men?

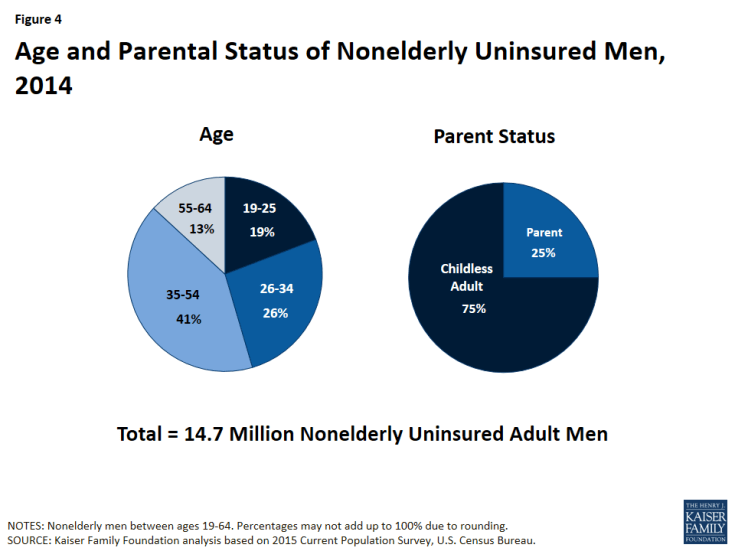

Nearly half (45%) of nonelderly uninsured men are young adults between ages 19-35 and three quarters are childless adults. However, this group includes men across the age spectrum and one quarter are fathers (Figure 4).

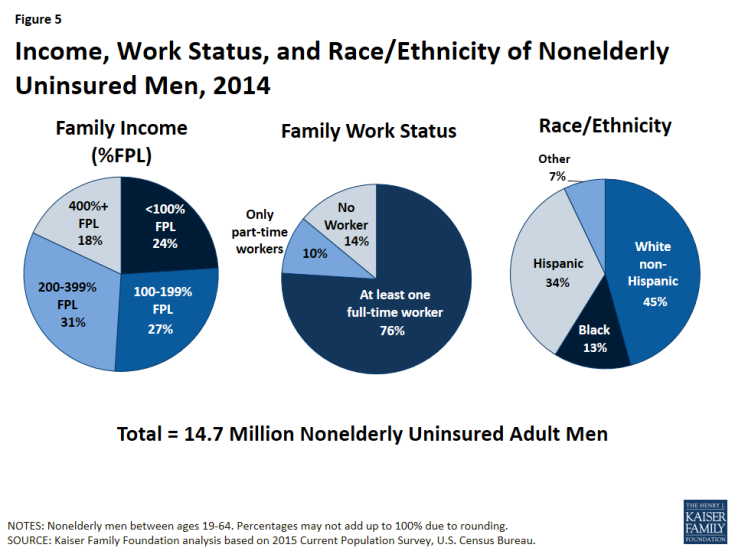

Most nonelderly uninsured men are in working families but have low incomes. Though provisions in the ACA aim to make coverage more affordable for low and moderate-income families, these income groups still make up the majority of the uninsured. More than three-quarters (76%) of nonelderly uninsured men live in a household with at least one full-time worker, but more than half have family income at or below 200% FPL ($40,320 per year for a family of 3 in 2016) (Figure 5).

Men of color represent a disproportionate share of uninsured men. While 37% of all nonelderly men are men of color, men of color account for over half (55%) of nonelderly uninsured men. In 2014, over one-third (34%) of nonelderly uninsured men were Hispanic, 13% were Black, and 7% identified as another non-White group, including Asian, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, or mixed race.

Why is health coverage for nonelderly men important?

Health insurance makes a difference in whether and when men get necessary medical care, where they get their care, and ultimately, how healthy they are. Health insurance also plays an important role in providing financial protection and stability to families.

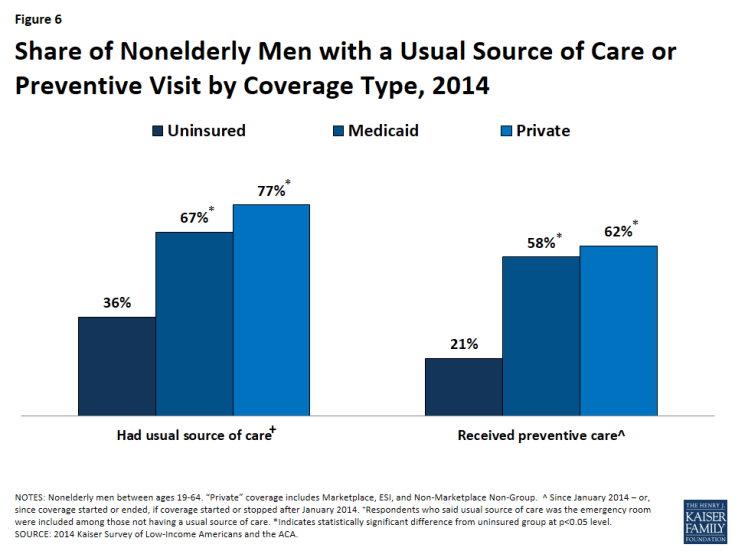

Nonelderly uninsured men are less likely to report having a usual source of care and receiving preventive care compared to those with health coverage (Figure 6). Only 36% of nonelderly uninsured men reported having a usual source of care compared to 67% of nonelderly men with Medicaid coverage and 77% of nonelderly men with private coverage. Additionally, nonelderly men with health coverage are more than two times as likely to receive preventive care compared to those who are uninsured.

Figure 6: Share of Nonelderly Men with a Usual Source of Care or Preventive Visit by Coverage Type, 2014

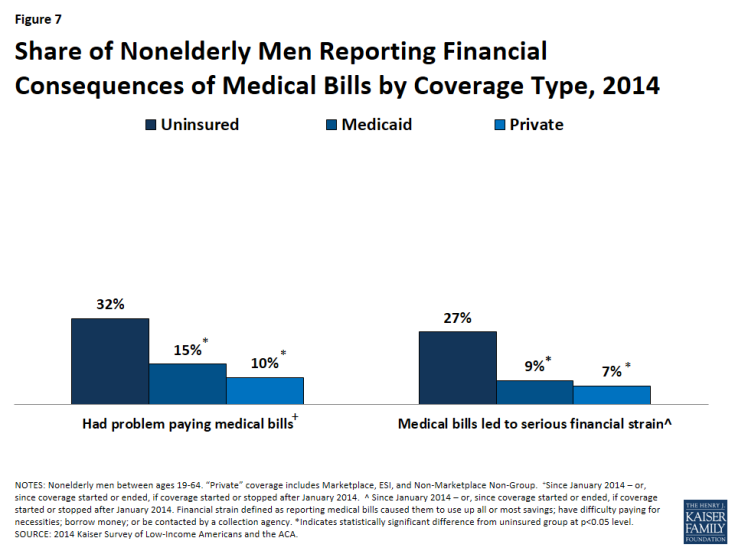

Uninsured men are at increased risk of financial strain due to medical bills compared to those with coverage. Nonelderly uninsured men are more likely (32%) than nonelderly men with Medicaid (15%) or nonelderly men with private coverage (10%) to report having trouble paying medical bills in 2014 (Figure 7). Men without coverage are also more likely than those who are insured to report serious financial strain due to medical bills. In 2014, more than one-quarter (27%) of nonelderly uninsured men reported that medical bills caused them to use up all or most of their savings, have difficulties paying for basic necessities, borrow money, or be contacted by a collection agency. In contrast, only 9% of nonelderly men with Medicaid and 7% of nonelderly men with private coverage experienced this type of financial strain due to medical bills.

Figure 7: Share of Nonelderly Men Reporting Financial Consequences of Medical Bills by Coverage Type, 2014

How many nonelderly uninsured men are eligible for coverage under the ACA?

The ACA fills historical gaps in Medicaid eligibility by extending Medicaid to nearly all nonelderly adults with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($27,821 for a family of three in 2016). With the June 2012 Supreme Court ruling, the Medicaid expansion effectively became optional for states. As of February 2016, 31 states and DC had adopted the Medicaid expansion under the ACA.4 The ACA also established Health Insurance Marketplaces where individuals can purchase insurance and allows for federal tax credits for such coverage for people with incomes from 100% to 400% FPL ($20,160 to $80,640 for a family of three in 2016). Tax credits are generally only available to people who are not eligible for other coverage.

Because the ACA envisioned low-income people receiving coverage through Medicaid, people with incomes below poverty are not eligible for Marketplace subsidies. Thus, in the 19 states not implementing the Medicaid expansion, some adults fall into a “coverage gap” – earning too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to qualify for premium tax credits. In addition, undocumented immigrants are ineligible for Medicaid coverage and barred from purchasing coverage through a Marketplace.

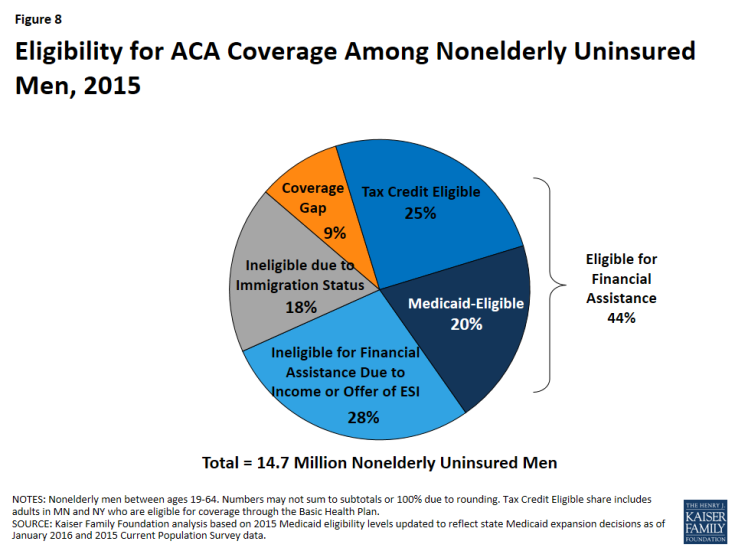

An estimated 44% of nonelderly uninsured men are eligible for financial assistance under the ACA (Figure 8). Of the nearly 15 million nonelderly uninsured men in the U.S. as of the beginning of 2015, a quarter (25%) is eligible for Marketplace premium tax credit subsidies and 20% are eligible for Medicaid. Nearly one in ten (9%) nonelderly uninsured men fall into the coverage gap in the states that have not adopted the Medicaid expansion. The remainder is not eligible for financial assistance because they have an offer of ESI or have income above the limit for premium tax credits (28%) or due to immigration status (18%). Patterns of eligibility vary by state, depending on state decisions about expanding Medicaid, premiums in the exchange, and underlying demographic factors such as poverty rates and access to employer coverage.

Nonelderly uninsured men in Medicaid expansion states are more likely to be eligible for coverage than those in non-expansion states (Figure 9 and Appendix). In Medicaid expansion states, over half (55%) of men are eligible for Medicaid or subsidized Marketplace coverage, including over one-third (35%) who are eligible for Medicaid. In contrast, in non-expansion states, one-third of (33%) nonelderly uninsured men are eligible for Medicaid or subsidized Marketplace coverage, with just 2% eligible for Medicaid. One in five (20%) nonelderly uninsured men falls into the coverage gap in non-expansion states.

Figure 9: Eligibility for ACA Coverage Among Nonelderly Uninsured Men by State Medicaid Expansion Status, 2015

What strategies can be used to reach and enroll eligible nonelderly uninsured men in health coverage?

With more than four in ten or over six million nonelderly uninsured men estimated to be eligible for coverage, reaching and enrolling these men into coverage would support continued coverage gains among the overall remaining uninsured. Moreover, increasing coverage among men would lead to improved access to care and increased financial protection from medical bills for them, recognizing that one-third of uninsured men reported trouble paying medical bills. While some longstanding outreach and enrollment strategies used to connect families to coverage may help reach and enroll uninsured men, targeted strategies for men will also be important, including strategies focused on reaching low-income fathers.

Eligible but uninsured men face a range of barriers to enrolling in coverage. Men face increased barriers to enrolling in coverage given the historic exclusion of many men from Medicaid prior to the ACA and them placing a relatively low priority on their own health and having health coverage. As such, messaging targeted to men will be important for overcoming these barriers, which include lack of information about the availability of health coverage and financial assistance, less motivation to seek out health coverage, wariness about engaging with government programs, and perceived difficulty with the application and enrollment process.5, 6

Providing outreach and one-on-one enrollment assistance through trusted individuals within the community is important for successful enrollment. Enrollment experiences to date point to the importance of conducting an array of outreach and enrollment initiatives through numerous local avenues, including churches, college campuses, beauty and barber shops, local grocery or community stores, libraries and extension centers.7 Recognizing that many uninsured men are in working families, small businesses and job placement sites may also be effective outreach sites. Identifying avenues that facilitate connections with men via trusted individuals will be key for increasing their enrollment. For example, low-income fathers may already be connected to “father-serving” organizations in their communities, making these organizations well positioned to help connect fathers to health coverage. These programs have men with similar life experiences that can serve as trusted messengers and may have an existing physical presence in the neighborhood. Other community-based organizations and agencies that serve men may also serve as effective points of connection, including workforce development programs, child support agencies, and justice system agencies.8

A combination of broad and targeted messages will be key for reaching and enrolling uninsured men. Individuals learn about health coverage options through multiple avenues, including word of mouth, mass media, and healthcare providers, and have varied preferences about where and how to receive information. Broad-based messages are effective in educating individuals about coverage, but targeted messages and efforts are important for reaching and enrolling hard-to-reach groups, including low-income men and fathers.9 Some messages that have been identified as effective for talking with low-income men and fathers about coverage include, discussing the importance of coverage for maintaining good health and the value of obtaining screenings and preventive care; emphasizing the affordability of coverage options, the availability of financial help, and the financial protections gained from having coverage; and highlighting how gaining coverage supports an individual’s ability to be an effective provider for the family.10,11 Messaging about the availability of free in-person enrollment assistance has also been identified as particularly useful.12 Findings also suggest that talking with fathers about their children’s health and health care coverage can offer an effective entry point for talking about their own health and health coverage.13

Conclusion

Health insurance makes a difference in whether and when people get necessary medical care, where they get their care, and ultimately, how healthy they are. Health coverage may also provide increased financial security. As of the beginning of 2015, there were still over 27 million uninsured nonelderly adults in the U.S. More than half of these uninsured adults were men – or nearly 15 million. An estimated 44% of these men, or nearly 6.5 million, are currently eligible for financial assistance under the ACA. Targeted outreach and enrollment efforts will be key for reaching and enrolling these uninsured men into coverage and achieving continued coverage gains.