Understanding Medicaid Hospital Payments and the Impact of Recent Policy Changes

Peter Cunningham, Robin Rudowitz, Katherine Young, Rachel Garfield, and Julia Foutz

Published:

Executive Summary

Executive Summary

Medicaid payments to hospitals and other providers play an important role in these providers’ finances, which can affect beneficiaries’ access to care. Medicaid hospital payments include base payments set by states or health plans and supplemental payments. Estimates of overall Medicaid payment to hospitals as a share of costs vary but range from 90% to 107%. While base Medicaid payments are typically below cost, the use of supplemental payments can increase payments above costs. Changes related to expanded coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) as well as other changes related to Medicaid supplemental payments could have important implications for Medicaid payments to hospitals. This brief provides an overview of Medicaid payments for hospitals and explores the implications of the ACA Medicaid expansion as well as payment policy changes on hospital finances. Key findings include the following:

- Overall, hospitals have benefitted financially from the ACA coverage expansions and the increase in Medicaid payments, especially in states that expanded Medicaid coverage. Analysis of the Medicare Cost Report data for 2013 and 2014 shows overall declines in uncompensated care from $34.9 billion to $28.9 billion in 2014 nationwide. Nearly all of this decline occurred in expansion states, where uncompensated care costs were $10.8 billion in 2014, $5.7 billion or 35% less than in 2013.

- While hospitals expect to benefit financially from the Medicaid expansion, they expect some gains from the reduction in uncompensated care to be offset by volume-generated increases in Medicaid payments that may be lower than cost. The data is not reliable enough to support nationwide analysis of the extent to which this has occurred, and the effect would vary across hospitals.

- Despite the decrease in uncompensated care, other changes to Medicaid payment policy (such as required reductions to disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments and policy changes to limit the use of other supplemental payments) are likely to have a more substantial effect on Medicaid hospital payment and overall hospital financial performance in the future. Ultimately the impact of reductions in supplemental payments will depend on decisions by state governments to offset reductions with increases to Medicaid base rates paid to hospitals.

Issue Brief

Introduction

Medicaid payments to hospitals and other providers play an important role in these providers’ finances, which can affect beneficiaries’ access to care. States have a great deal of discretion to set payment Medicaid rates for hospitals and other providers. Like other public payers, Medicaid payments have historically been (on average) below costs, resulting in payment shortfalls.1 However, hospital payment rates are often bolstered by additional supplemental payments in the form of Disproportionate Share Hospital Payments (DSH) and other supplemental payments. After accounting for these payments, many hospitals receive Medicaid payments that may be in excess of cost. Understanding how much Medicaid pays hospitals is difficult because there is no publicly available data source that provides reliable information to measure this nationally across all hospitals. Different data sources use different definitions of what counts as payments and costs, so estimates are sensitive to these data limitations.

Understanding the components of Medicaid payment to hospitals and how much Medicaid pays hospitals is important given the many policy changes taking place. First, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is leading to changes in hospital payer mix, especially in states adopting the Medicaid expansion where studies have shown a decline in self-pay discharges and a corresponding increase in Medicaid discharges.2,3,4 Second, the ACA calls for reductions in DSH payments, and other federal policy changes are focused on limiting the use of supplemental payments. These changes could have important implications for Medicaid payments to hospitals at the same time that Medicaid is a growing share of hospital payer mix, especially among safety net hospitals that serve a disproportionately high number of Medicaid and uninsured patients.

This brief provides an overview of how Medicaid pays hospitals and discusses changes related to the ACA and supplemental payments that will have implications for hospital financing. It draws on existing literature and published reports as well as information collected from semi-structured interviews with hospital associations and federal agencies.5 Interviews focused on respondents’ perspectives of how hospitals were likely fare under the ACA and changes in Medicaid payment policy. In addition, we used data from the 2013 and 2014 Medicare cost reports to try to measure Medicaid payment and uncompensated care in 2013 and 2014.

Background

How Does Medicaid Pay Hospitals?

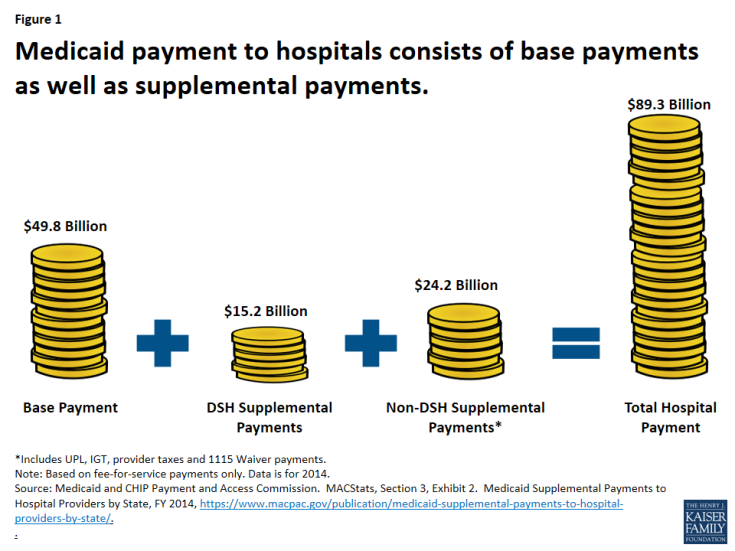

Hospital payment for a particular patient or service is usually different than the charge for that service (i.e., prices set by the hospital) or the cost to the hospital of providing the service (i.e., actual incurred expenses). In Medicaid, payment rates, sometimes called the “base rate,” are set by state Medicaid agencies for specific services used by patients. In addition, Medicaid also may make supplemental payments to hospitals (Figure 1).6

Base Payment. The base payment rates are reimbursed through fee-for-service or managed care arrangements for services provided to Medicaid beneficiaries. States have wide discretion in setting these rates. As discussed below, base rates are often not reflective of charges or costs for services.

Supplemental Payments. Supplemental payments are payments beyond the base rate that may or may not be tied to specific services. States often use Upper Payment Limits (UPL), Intergovernmental Transfers (IGT), provider taxes, or waivers to finance and direct supplemental payments. UPL rules allow states to make up the difference between a reasonable estimate of what Medicare would pay and Medicaid payments (in aggregate within a type and class of provider). IGTs or provider taxes are often used to generate the non-federal share for Medicaid payments that are then redistributed to providers as additional Medicaid payments. In addition, Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments are made to hospitals serving high proportions of Medicaid or low-income patients.

Nationally, all supplemental Medicaid payments combined amounted to 44 percent of Medicaid fee-for-service payments to hospitals in 2014.7 Non-DSH supplemental payments (which includes UPL, IGT, and revenue generated from provider taxes) alone accounted for 15 percent of Medicaid fee-for-service payments. Almost all states make Medicaid DSH payments to hospitals, and most states also use some other form of supplemental payments, although both the amount of supplemental payments and how they are distributed to hospitals varies considerably across states.8 Supplemental payments as a proportion of total Medicaid fee-for-service payments to hospitals varies from a low of about 2 percent in North Dakota, South Dakota, and Maine to more than two-thirds in Vermont and Pennsylvania.9

How Much Does Medicaid Pay Hospitals?

Since payment rates are either negotiated (with health plans) or set by the federal government for Medicare or state governments for Medicaid fee-for-service, payments that hospitals receive for patient care do not necessarily reflect what hospitals charge for those services or the cost of providing those services;10 rather, hospitals may receive payments above costs or below costs. Payments below costs would result in a “shortfall.”

Due to data challenges and differences in what is counted as a Medicaid cost and payment (see Appendix A), estimates of Medicaid payments to hospitals vary. The American Hospital Association (AHA) estimated that Medicaid payments to hospitals amounted to 90 percent of the costs of patient care in 2013, while Medicare paid 88 percent of costs; by contrast, hospitals received considerable overpayment from private insurers, amounting to 144 percent of costs.11,12 The most recent Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) report to Congress, based on the 2011 DSH audit reports, shows that DSH hospitals were paid an average of 93 percent of total Medicaid costs, accounting for base Medicaid payments and non-DSH supplemental payments. After DSH payments, hospitals received 107% of costs on average nationally but ranged from 81 percent in the lowest paying state to 130 percent in the highest paying state.13 Our own analysis of the Medicare Cost Reports finds that Medicaid payments covered 93% of costs in 2014.14 However, we find great variation at the state or individual hospital level, indicating that hospitals may have very different experiences of the extent to which Medicaid payment covers Medicaid costs.

How has the Medicaid expansion affected hospital finances?

Expanded health insurance coverage through the ACA (both Medicaid and private insurance) is having a major impact on hospital payer mix for many hospitals. A number of reports show increases in Medicaid discharges and declines in uninsured or self-pay discharges for hospitals located in states that implemented the Medicaid expansion. In contrast, hospitals located in states that did not expand Medicaid are not seeing these large shifts in payer mix. 15,16,17

One report that examined the nation’s largest not-for-profit hospital system (Ascension Health) was able to examine not only changes in discharges but also changes in hospital revenues and costs. Like other studies, data from Ascension Health hospitals showed that hospitals in states that expanded Medicaid experienced larger increases in Medicaid discharge volumes and patient revenue from 2013 to 2014 compared to hospitals in states that did not expand Medicaid. Ascension hospitals in expansion states also observed a much larger decrease in uninsured/self-pay volumes as well as charity care.18 Overall, Ascension Health hospitals in Medicaid expansion states observed a $35 million decrease in charity care between 2013 and 2014, but they also saw Medicaid shortfall amounts rise by $23 million, resulting in a net decrease of $12 million in the costs of care to the poor.19 Shortfalls grew as a result of both increases in Medicaid volume and payment rate changes in some states. Replicating the Ascension analysis for hospitals nationally is difficult due to limited reliable data.

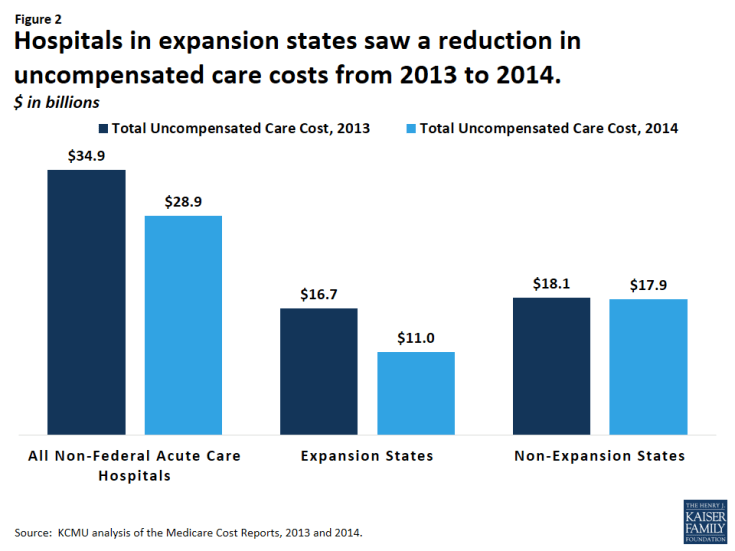

The cost of uncompensated care has declined among hospitals in Medicaid expansion states, while such costs have remained flat among hospitals in states that did not expand Medicaid. Analysis of the Medicare Cost Report data for 2013 and 2014 shows overall declines in uncompensated care. In 2013, total uncompensated care costs for hospitals (including charity care costs and bad debt) were $34.9 billion, with hospitals in expansion states incurring about $16.7 billion and hospitals in non-expansion states incurring about $18.1 billion.20 In 2014, uncompensated care fell to $28.9 billion nationwide, a $6 billion or 17% drop, with nearly all of the decrease occurring in expansion states (where uncompensated care costs were $11 billion in 2014, $5.8 billion or 35% less than the year before). In non-expansion states, the change in uncompensated care was nearly flat between 2013 and 2014, dropping just 1% (or $0.2 billion) to $17.9 billion in 2014 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Hospitals in expansion states saw a reduction in uncompensated care costs from 2013 to 2014. $ in billions

Unfortunately, we are not able to quantify how much of the decrease in hospital uncompensated care costs was offset by increases in Medicaid shortfall amounts, because such data are not reliable in the Medicare Cost Reports (i.e. supplemental Medicaid payments are likely to be under-reported). While the experience of the Ascension Health system suggests that rising Medicaid shortfalls are offsetting the potential financial benefit of lower uncompensated care costs, this outcome is likely to vary substantially across hospitals.

Whether hospitals come out ahead financially under the ACA will depend on numerous factors – many of which are unrelated to Medicaid. The ACA included a number of restrictions on Medicare payments for hospitals and expanded coverage has also resulted in markets shifts and new competition. Hospitals also may see shifts in patient acuity, Medicaid payment rate changes or other changes in Medicaid payment policy. In addition, hospitals are constantly implementing strategies to increase revenue (e.g. diversify payer mix) and reduce the costs of providing services. Many safety net hospitals are trying to diversify their payer mix by changing their “safety net image” in the community, competing more aggressively for privately insured patients, retaining the privately insured patients they already have, and expanding services beyond inner city service areas where they are typically located.21 Thus, Medicaid expansion is just one of many factors that will influence hospitals’ financial viability in the future.

Given this variation and difficulties with underlying data, better data are needed to capture how hospital finances are faring under the ACA, and specifically how Medicaid revenues and shortfalls are changing. Stakeholders interviewed for this project thought that the Medicaid expansion would be a financial benefit to hospitals, but payment levels were a concern; however, these concerns were secondary to broader concerns about upcoming and potential changes to Medicaid supplemental payments.

What payment policy changes could affect Medicaid hospital payments?

Hospitals are facing several policy changes that may affect Medicaid payments. Over time, state budget pressures have resulted in an increasing reliance on supplemental payments (versus base payments) to finance Medicaid hospital services. However, a number of upcoming policy changes, including reductions in DSH payments and limits on other supplemental payments, will restrict the use of supplemental payments. Federal officials believe that reform of Medicaid supplemental payments is needed to make payment more transparent, targeted, and consistent with delivery system reforms that reduce health care costs, and increase quality and access to care. However, these policy changes are causing concern among hospitals that have long been dependent on Medicaid revenue for their financial viability.22,23,24 In addition, payment changes are occurring against the backdrop of coverage expansions under the ACA, which are affecting payer mix for some hospitals.

Changes in Base Payment Rates

Changes in state reimbursement rates for hospitals have a big effect on Medicaid hospital financing, especially for safety net hospitals that serve a large number of Medicaid patients. Each year, states must balance their budgets, and consideration of Medicaid payment rates for providers and managed care organizations factor in to these discussions. In general, increases in base rates have lagged behind increases in costs during economic downturns as states often restrict (freeze or reduce) provider rates. Even as the economy has recovered, in fiscal years 2015 and 2016, there were more states restricting (freezing or cutting) rates for Medicaid hospital inpatient care than there were states increasing rates.25 While the economy is improving and resources are not as scarce as during a recession, states balance the need to increase Medicaid payment rates to ensure provider participation and access with overall budget decisions.

Changes in Medicaid DSH Funding

In 2014, federal DSH allotments totaled $11.7 billion.26 Under current law, DSH spending is limited by annual federal allotments and individual hospital limits (hospitals cannot receive DSH payments in excess of uncompensated care costs). The ACA calls for reductions in Medicaid DSH payments, originally scheduled to begin in 2014 but delayed until 2018.27 These reductions will amount to $43 billion between 2018 and 2025; reductions start at $2 billion in FY 2018 and increase to $8 billion by FY 2025. The ACA requires the Secretary of HHS to develop a methodology to allocate the reductions that must take into account certain factors that would allocate larger percentage reductions on states with the lowest percentages of uninsured individuals and states that do not target DSH payments to hospitals with high levels of uncompensated care. It is unclear if or how HHS will adjust the DSH reductions to account for the fact that some states may have higher uninsured rates because they have opted to not implement the Medicaid expansion. MACPAC analysis shows that current state DSH allocations are not tied to a hospital’s share of Medicaid and other low-income patients, its uncompensated care burden, and its delivery of essential community services.28

In general, many hospitals and hospital associations are skeptical that the increase in patient revenue under the ACA will make up for the loss of Medicaid DSH funds, although the impact will vary depending on hospitals’ prior dependence on Medicaid DSH funding as well as federal and state government decisions on how the remaining DSH funds will be distributed across states and hospitals. Safety net hospitals are particularly vulnerable because of their high dependence on Medicaid DSH funds, high numbers of uninsured, few privately insured or Medicare patients, and generally weaker financial condition.29 An analysis of California concluded that reductions in DSH payments to the state’s public hospitals would not be fully offset by increased revenue from paying patients due to the high number of people who would remain uninsured, low Medicaid reimbursement rates, and the rising costs of care.30 Analyses by the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation also estimated that DSH cuts will put a strain on hospitals, possibly leading to reductions in hospital medical staff and services.31

Changes in Other Supplemental Payments

While states’ reliance on supplemental payments as a source of revenue for hospitals has increased, lack of data and transparency on state’s use of supplemental payments makes federal oversight of these programs difficult.32 Federal officials are working to reform how states use supplemental payments in managed care and waivers, as well as the use of provider taxes.

Managed Care Rules. While UPL payments to hospitals have always been restricted to fee-for-service payment only, some states have used pass-through mechanisms to direct supplemental payments to selected hospitals through managed care plans. The Medicaid managed care rules originally proposed by the federal government would have restricted states’ ability to direct supplemental payments to providers through managed care plans.33 Under the Final Rule published in May 2016, these supplemental payments to hospitals would be phased out over 10 years (2017-2027), by 10 percentage points each year. So, while still an area of concerns, states and hospitals have more time to make rate adjustments over time.

DSRIP. The Delivery System Reform and Incentive Programs (DSRIP) allow states to use supplemental payments for delivery system reforms in their Medicaid programs. These programs have been implemented through Section 1115 waivers in eight states, including California, Texas, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico, Kansas, and New York.34,35 Supplemental payments through DSRIP are being used to achieve particular goals, such as improved quality, outcomes, access to care and population health. In most states with DSRIP programs, public hospitals are contributing all or most of the non-federal share of funding for these programs.36 The DSRIP programs are temporary, with the expectation that states and providers can transform their delivery systems so that they are more efficient, less costly, have lower use of hospital inpatient care, and more use of primary and preventive care. While these payments are included under broad waivers that are budget neutral to the federal government, the amount of funding allocated for DSRIP programs is significant ($3.3 billion in California, $6.6 billion in Texas, $6.4 billion in New York)37, and the phase-out of this funding will have implications for states and providers. In renewing California’s DSRIP program in December 2015, funding is scheduled to phase down by 10% in year four and by 15% in year five.38

Safety Net Care Pools. Federal policy makers also have been focused on reforming the use of Medicaid Section 1115 demonstration waivers to fund state uncompensated care pools in nine states. Officials laid out the principles for which such funds were to be used, including: (1) funds should not pay for the costs that would be covered in a Medicaid expansion; (2) they should support services provided to Medicaid beneficiaries and low-income uninsured individuals, and; (3) provider payment should promote provider participation and access, and should support plans in managing and coordinating care.39 To the extent that this funding has been used to supplement Medicaid base rates for certain hospitals, changes to these funding streams will affect hospital finances. The agreement to renew Florida’s Low Income Pool – which reduced funds for the pool – included a $400 million increase in base rates to providers. In May 2016, Texas received a 15 month extension of their waiver; the letter states that if CMS and the state cannot reach agreement during this extension period, CMS expects that the Uncompensated Care pool will not be renewed at the end of 2017 and that DSRIP will decrease by 25% each year starting in 2018.40

Provider Taxes. Provider taxes are an integral source of Medicaid financing governed by long-standing regulations. Currently, all but one state (Alaska) reported a provider tax in FY 2015.41 Often provider taxes are used to bolster Medicaid payment rates for hospitals; however, these taxes can also be used to support state general revenues. In Connecticut, the state has been retaining more of the provider tax to address state budget deficits instead of supporting hospitals.42 The state hospital association estimates that this has effectively decreased overall Medicaid payments from 50 percent of costs to 41 percent.43 In addition to state decisions about how to use funding from provider taxes, Congress is currently considering proposals to limit the use of provider taxes. This action would restrict states’ flexibility to finance their share of Medicaid and could therefore shift additional costs to states or result in program cuts. Since states use provider taxes differently, limits would have different effects across states.

Conclusion

At this point, it is unclear how recent and upcoming policy changes in Medicaid will affect the financial viability of hospitals. Early analysis of the Medicare Care Report data show national declines in uncompensated care, especially in expansion states, although the data do not permit reliable estimates of trends in Medicaid payment amounts. However, hospital margins are influenced by numerous factors, the health care and policy environment is in flux, and some hospitals will be better able to adapt to these changes than others. There is much concern from hospitals – especially safety net hospitals – about the decrease in Medicaid DSH funds and other changes in supplemental payments that they have depended on for years. Most stakeholders from the hospital industry that we talked to thought that even after accounting for increases in Medicaid shortfall, the Medicaid expansion was a financial benefit, but changes to supplemental payments could have a much larger negative effect on hospital finances. The overall impact of changes to supplemental payments also will depend on how much states adjust base payment rates to compensate for changes to supplemental payments. Better data and monitoring of the effects of coverage changes as well as policy changes related to the supplemental payments will help to better evaluate hospitals financial well-being and the ability of safety net hospitals to serve Medicaid and uninsured persons.

Appendix

Appendix A: Measuring Medicaid Payments to Hospitals

No data source consistently collects information on Medicaid costs and payment, and different estimates of Medicaid payment as a share of costs use different definitions of Medicaid costs and payments. Thus, estimates of Medicaid payment as a percent of costs are sensitive to the specific data source and definitions used to make the estimates. For example, when measuring Medicaid hospital payments, some data sources include supplemental payments, while others do not. In some data sources, these payment streams are not identified, making it difficult to understand what is and is not included. Further, in some cases, Medicaid costs may be defined to include only costs for Medicaid-covered services, while in others, the definition may include unpaid costs for services provided to Medicaid patients when Medicaid was not the primary payer—for example, costs for Medicare-funded services provided to people dually eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare.

Three main sources of estimating Medicaid payment relative to costs are the Medicare cost reports, the DSH Audit Reports and the American Hospital Association survey. These sources vary in the data they collect and the definitions of costs and payments that they enable. Each of these data sources may underreport other Medicaid supplemental payments, which may understate total Medicaid payments, and the data likely does not net out provider contributions towards the non-federal share, which are necessary to calculate net Medicaid payments and may contribute to overstating total Medicaid payments.

Medicare Cost Reports. The Medicare Cost Reports (MCR) are annual reports that all Medicare-certified institutional providers are required to submit to Medicare. It is the only publicly available source of detailed financial data for most of the acute care hospitals in the U.S. These reports contain provider information such as facility characteristics, utilization data, cost and charges by cost center (in total and for Medicare), Medicare settlement data, and financial statement data that are used as part of the annual settlement between the federal government and the provider.1 These cost reports are designed to collect data necessary for Medicare reimbursement and thus do not verify or require Medicaid data, leading to questions about how reliable these data are for Medicaid payment analyses. Hospitals are not required to report DSH payments separately, but DSH payments are included as Medicaid revenues in these reports, and the reports only include costs for Medicaid-covered services.

Medicaid DSH Audit Reports. The Medicaid DSH audit reports are required annual reports that states must submit to the federal government describing DSH payments made to each DSH hospital.2 In these reports, hospitals explicitly report DSH payments. DSH audits also include unpaid costs for services provided to Medicaid patients when Medicaid was not the primary payer. The primary limitation of this data source is that they exclude hospitals that do not receive DSH payments, which are likely to differ substantially from DSH hospitals in the amount of overpayment or underpayment from Medicaid.

American Hospital Association Reports (AHA). The AHA uses data from their annual hospital survey to provide an estimate of Medicaid (and Medicare) payments relative to costs. In their survey, AHA obtains information on each hospitals’ net and gross Medicaid payments, DSH, and supplemental payments. They calculate a cost-to-charge ratio and use this to determine the rate of underpayment for all hospitals. In their underpayment calculation, they include all payment adjustments.3 While AHA publishes annual reports on overall hospital uncompensated care costs, as well as Medicare and Medicaid underpayments, the detailed financial data are not available on their public use files.

As a result of these differences, as well as limitations in the underlying data, estimates of Medicaid payment as a share of cost vary (see Table A1). However, most estimates indicate that Medicaid payments cover most (more than 90%) costs, with one estimate indicating that some hospitals (those that receive DSH payments) receive Medicaid reimbursement in excess of costs.

| Table A1: Estimates of Medicaid Payments as a Share of Costs | ||||

| Source | Data | Year | Estimate of Medicaid Payment as a Share of Medicaid Cost | Notes |

| American Hospital Association (AHA)4 | AHA annual survey | 2013 | 90% |

|

| Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC)5 | DSH Audit Reports | 2011 | 93% excluding DSH and 107% including DSH |

|

| Authors’ analysis | Medicare Cost Reports | 2014 | 93% |

|

Endnotes

Issue Brief

American Hospital Association, “Table 4.4: Aggregate Hospital Payment-to-cost Ratios for Private Payers, Medicare,” in Trendwatch Chartbook 2015 (Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association, 2015), http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/chartbook/2015/table4-4.pdf.

Deborah Bachrach, Patricia Boozang, and Mindy Lipson, The Impact of Medicaid Expansion on Uncompensated Care Costs: Early Results and Policy Implications for States (Princeton, NJ: The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, State Health Reform Assistance Network, June 2015), http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2015/06/the-impact-of-medicaid-expansion-on-uncompensated-care-costs.html.

Robin Rudowitz and Rachel Garfield, New Analysis Shows States with Medicaid Expansion Experienced Declines in Uninsured Hospital Discharges (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, September 2015), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/new-analysis-shows-states-with-medicaid-expansion-experienced-declines-in-uninsured-hospital-discharges.

Sayeh Nikpay, Thomas Buchmueller, and Helen G. Levy, “Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion Reduced Uninsured Hospital Stays In 2014,” Health Affairs. 35, no. 1 (2016): 106-10, http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/35/1/106.abstract.

Organizations interviewed for this report included the American Hospital Association, America’s Essential Hospitals, the Connecticut Hospital Association, the California Public Hospital Association, the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Examining the Policy Implications of Medicaid Non-Disproportionate Share Hospital Supplemental Payments,” chap. 6 in March 2014 Report to the Congress on Medicaid and CHIP (Washington, DC: March 2014), 183-209, https://www.macpac.gov/publication/report-to-the-congress-on-medicaid-and-chip-314/.

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Medicaid Supplemental Payments to Hospital Providers by State, FY 2014” Exhibit 23 in December 2015 MACStats: Medicaid and CHIP Data Book. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/EXHIBIT-23.-Medicaid-Supplemental-Payments-to-Hospital-Providers-by-State-FY-2014-millions.pdf

Ibid.

Ibid.

Uwe Reinhardt, “The pricing of U.S. hospital services: Chaos behind a veil of secrecy,” Health Affairs, 25, no. 1 (2006): 57-69, http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/25/1/57.full.pdf+html.

American Hospital Association, “Table 4.4: Aggregate Hospital Payment-to-cost Ratios for Private Payers, Medicare,” in Trendwatch Chartbook 2015 (Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association, 2015), http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/chartbook/2015/table4-4.pdf.

AHA estimates that in 2014, Medicare paid 89 percent of costs for Medicare patients and Medicaid paid 90 percent of costs ofr Medicaid patients. See: American Hospital Association, “Underpayment by Medicare and Medicaid Fact Sheet: Underpayment by Medicare and Medicaid Fact Sheet,” (Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association, 2016) http://www.aha.org/content/16/medicaremedicaidunderpmt.pdf

MACPAC’s analysis showed similar findings using the Medicare Cost Reports (from among a subset of hospitals with complete data from both sources). Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Improving Data as the First Step to a More Targeted Disproportionate Share Hospital Policy,” chap. 3, March 2016 Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP, (Washington, DC: March 2016), 56-73, https://www.macpac.gov/publication/improving-data-as-the-first-step-to-a-more-targeted-disproportionate-share-hospital-policy/.

Using data from Worksheet S-10 in the 2013 and 2014 Medicare Costs Reports, we calculated revenue over costs as net Medicaid revenue divided by the product of Medicaid charges and the cost to charge ratio. We restricted the data to just non-federal acute care hospitals that had both 2013 and 2014 data. We adjusted spending amounts to reflect the entire year. We treated blanks in the data as missing data, and did not include them in the rate. Worksheet S-10 (“Hospital Uncompensated and Indigent Care Data”), 2013 and 2014 Medicare Cost Reports, https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Downloadable-Public-Use-Files/Cost-Reports/Cost-Reports-by-Fiscal-Year.html.

Bachrach et al., op. cit.

Rudowitz and Garfield, op. cit.

Nikpay, Buchmueller, and Levy, op. cit.

Peter Cunningham, Rachel Garfield, and Robin Rudowitz, How are Hospitals Faring under the Affordable Care Act? Early Experiences from Ascension Health. (Washington DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, October 2014), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/how-are-hospitals-faring-under-the-affordable-care-act-early-experiences-from-ascension-health/

Ibid., Table 5.

Using the Worksheet S-10 data from the 2013 and 2014 Medicare Cost Reports, we calculated uncompensated care by summing bad debt costs and charity care costs. As we did when calculating the revenue over costs, we restricted the data to non-federal acute care hospitals that had both 2013 and 2014 data. We also adjusted spending to reflect the entire year. By linking the Medicare Cost Report data to the American Hospital Association Hospital Data, available through the AHA Data Viewer, we identified the location of each hospital. We categorized all states that had expanded by December 31, 2014 as “expansion states” and all others as “non-expansion states.”

Teresa Coughlin, Sharon Long, Rebecca Peters, Robin Rudowitz, and Rachel Garfield, Evolving Picture of Nine Safety-Net Hospitals: Implications of the ACA and Other Strategies (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, April 2015), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/evolving-picture-of-nine-safety-net-hospitals-implications-of-the-aca-and-other-strategies/.

America’s Essential Hospitals, “Our View: Essential Hospitals Rely on Medicaid Supplemental Payments,” (Washington DC: America’s Essential Hospitals, March 2016) http://essentialhospitals.org/policy/essential-hospitals-rely-on-supplemental-payments/.

Christopher Weaver, “Hospitals Expected More of a Boost From Health Law,” Wall Street Journal, June 3, 2015, http://www.wsj.com/articles/hospitals-expected-more-of-a-boost-from-health-law-1433304242.

Kentucky Hospital Association, “Code Blue: Many Kentucky Hospitals Struggling Financially Due to Health System changes,” (Louisville, KY: Kentucky Hospital Association, April 2015) http://www.new-kyha.com/Portals/5/NewsDocs/Code%20Blue%20Report%20Web.pdf.

Vernon Smith, Kathleen Gifford, Eileen Ellis, Robin Rudowitz, Laura Snyder, and Elizabeth Hinton, Medicaid Reforms to Expand Coverage, Control Costs and Improve Care. Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2015 and 2016. (Kaiser Family Foundation and National Association of Medicaid Directors, October 2015) https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-reforms-to-expand-coverage-control-costs-and-improve-care-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2015-and-2016/.

79 Fed. Reg. 11436 – 11445 (February 28, 2014), available at https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2014/02/28/2014-04032/medicaid-program-preliminary-disproportionate-share-hospital-allotments-dsh-for-fiscal-year-fy-2014.

42 U.S.C. § 1396r-4(f)(7). See https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/1396r-4 .

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Analysis of Current and Future Disproportionate Share Hospital Allotments,” chap. 2, March 2016 Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP, (Washington, DC: March 2016), 21-54, https://www.macpac.gov/publication/analysis-of-current-and-future-disproportionate-share-hospital-allotments/.

Evan Cole, Daniel Walker, Arthur Mora, Mark Diana, “Identifying Hospitals That May Be at Most Financial Risk from Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital Payment Cuts,” Health Affairs, 33, no. 11 (2014): 2025-2033, http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/33/11/2025.abstract.

Katherine Neuhausen, Anna Davis, Jack Needleman, Robert Broook, David Zingmond, and Dylan Roby. “Disproportionate-Share Hospital Payment Reductions May Threaten the Financial Stability of Safety-Net Hospitals.” Health Affairs, 33, no. 6 (2014): 988-996, http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/33/6/988.abstract.

Office of the New York City Comptroller, Holes in the Safety Net: Obamacare and the Future of New York City’s Health and Hospitals Corporation, (New York, NY: Office of the New York City Comptroller, May 2015), http://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/Holes_in_the_Safety_Net.pdf.

Government Accountability Office, “Medicaid: Improving Transparency and Accountability of Supplemental Payments and State Financing Methods,” (Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office, November 2015), http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-195T.

Moira Forbes and Chris Park, “Issues in Medicaid Managed Care Rate Setting,” (Washington DC: Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, May 2015) https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Issues-in-Medicaid-Managed-Care-Rate-Setting.pdf.

Alexandra Gates, Robin Rudowitz and Jocelyn Guyer, An Overview of Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Waivers (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, September 2014), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/an-overview-of-delivery-system-reform-incentive-payment-waivers/.

Jocelyn Guyer, Naomi Shine, Robin Rudowitz, and Alexandra Gates, Key Themes From Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Waivers in 4 States (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, April 2015), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/key-themes-from-delivery-system-reform-incentive-payment-dsrip-waivers-in-4-states/.

Gates, Rudowitz and Guyer, op. cit.

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, June 2015 Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP, (Washington, DC: June 2015), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/June-2015-Report-to-Congress-on-Medicaid-and-CHIP.pdf

Letter from CMS to Mari Cantwell, Chief Deputy Director Department of Health Care Services, California. (Washington, DC: CMS, December 30, 2015). https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ca/medi-cal-2020/ca-medi-cal-2020-ca.pdf

Letter from CMS to Justin Senior, Deputy Secretary for Medicaid, State of Florida, (Washington, DC: CMS, May 21, 2015), https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/fl/Managed-Medical-Assistance-MMA/fl-medicaid-reform-lip-ltr-05212015.pdf.

Letter from CMS to Gary Jessee, Associate Commissioner for Medicaid/CHIP, State of Texas. (Washington, DC: CMS, May 2016). https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/tx/tx-healthcare-transformation-ca.pdf

Smith, Gifford, Ellis, Rudowitz, Snyder, and Hinton, op. cit.

Arielle Levin Becker, “CT Hospitals Say Obamacare Hasn’t Cut Uncompensated Care,” CT Mirror, September 29, 2014, http://ctmirror.org/2014/09/29/ct-hospitals-say-obamacare-hasnt-cut-uncompensated-care/.

Interview with Connecticut Hospital Association.

Appendix

“Cost Reports,” CMS, https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Downloadable-Public-Use-Files/Cost-Reports/ and “Healthcare Cost Report Information System,” ResDAC, https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/hcris.

“Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Payments,” CMS, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/financing-and-reimbursement/medicaid-disproportionate-share-hospital-dsh-payments.html.

American Hospital Association, “Underpayment by Medicare and Medicaid Fact Sheet,” op. cit.

Ibid. Telephone conversation with Caroline Steinberg from the AHA Policy Division provided additional information used in notes.

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, March 2016 Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP, (Washington, DC: March 2016), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/March-2016-Report-to-Congress-on-Medicaid-and-CHIP.pdf.