The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Studies from January 2014 to January 2020

Impacts on Coverage

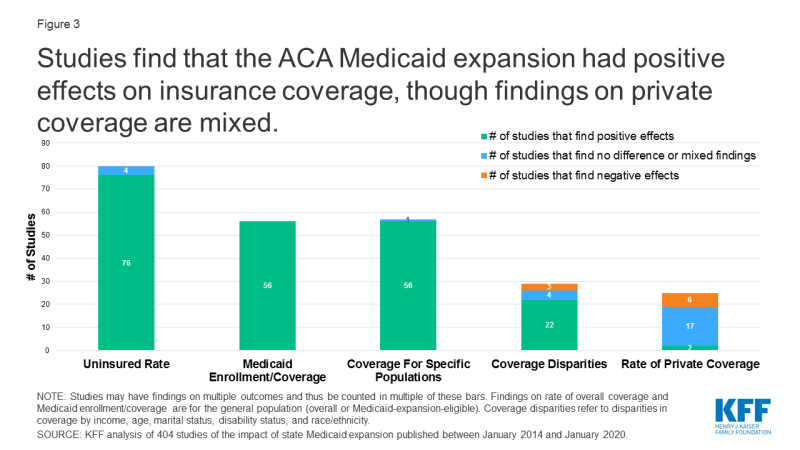

Studies find positive effects of Medicaid expansion on a range of outcomes related to insurance coverage (Figure 3). In addition to changes in uninsured rates and Medicaid coverage, both overall and for specific populations, studies also consider private coverage and waiver implications.

Figure 3: Studies find that the ACA Medicaid expansion had positive effects on insurance coverage, though findings on private coverage are mixed.

Uninsured Rate and Medicaid Coverage Changes

States expanding their Medicaid programs under the ACA have seen large increases in Medicaid enrollment. These broad coverage increases have been driven by enrollment of adults made newly eligible for Medicaid under expansion. Enrollment growth also occurred among both adults and children who were previously eligible for but not enrolled in Medicaid (known as the “woodwork” or “welcome mat” effect). Some, but not all, research finds evidence of reduced coverage churn in expansion compared to non-expansion states.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60

Numerous analyses demonstrate that Medicaid expansion states experienced large reductions in uninsured rates that significantly exceed those in non-expansion states. The sharp declines in uninsured rates among the low-income population in expansion states are widely attributed to gains in Medicaid coverage. Declines began in 2014, and some studies showed that expansion-related enrollment growth in Medicaid and declines in uninsured rates in expansion states continued in 2015, 2016, and 2017 and that the gap between coverage rates in expansion and non-expansion states continued to widen in the years after 2014. Two studies found that despite a nationwide increase in uninsured rates from 2016 to 2017, uninsured rates remained stable in states that had expanded Medicaid and coverage losses were concentrated in non-expansion states.61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137

Several studies identified larger coverage gains in expansion versus non-expansion states for specific vulnerable populations. While the list of specific populations studied is long, studies include: individuals across the lifespan (children, young adults, women of reproductive age with and without children, and the near-elderly), lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults, the unemployed, low-income workers, justice-involved individuals, homeless individuals, noncitizens, people living in households with mixed immigration status, migrant and seasonal agricultural workers, and early retirees. Other populations that experienced coverage gains include those with specific medical conditions or needs such as prescription drug users, people with substance use disorders including opioid use disorders, people with HIV, people with disabilities, low-income adults who screened positive for depression, adults with diabetes, cancer patients/survivors, adults with a history of cardiovascular disease or two or more cardiovascular risk factors, and veterans.138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194

Most analyses that looked at rural/urban coverage changes find that Medicaid expansion has had a particularly large impact on Medicaid coverage or uninsured rates in rural areas. Studies have found that Medicaid expansion reduced or eliminated disparities in coverage between adults living in rural vs. urban areas. However, as noted below, research on coverage effects in rural versus urban areas was mixed.195 196 197 198

Studies show larger Medicaid coverage gains and reductions in uninsured rates in expansion states compared to non-expansion states occurred across most or all of the major racial/ethnic categories. Additional research also suggests that Medicaid expansion has helped to reduce disparities in coverage by income, age, marital status, disability status, and, in some studies, race/ethnicity.199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220 221 222 223

A minority of coverage studies show no effect or mixed results of expansion in certain areas. Many of these findings were included in studies that had additional findings related to coverage or disparity improvements and are also cited above. Some findings within three studies did not show greater coverage changes for rural areas. A limited number of studies found that expansion was not significantly associated with changes in the uninsured rate among certain specific groups, as Medicaid coverage gains in expansion states were offset larger private insurance gains in non-expansion states for these groups. Findings within four studies suggested that expansion was associated with an increase in coverage disparities (by gender in one study, by race/ethnicity in another, and by marital status among women in two others). In addition, one study showed no significant differences in churn rates among low-income adults between 2013 and 2015 based on the state’s expansion policy.224 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 236 237 238 239 240 241 242 243 244 245 246 247

Private Coverage and Waiver Implications

Some studies exploring the effects of Medicaid expansion on private insurance coverage found no evidence of Medicaid expansion coverage substituting for private coverage including employer-sponsored insurance, while other studies showed declines in private coverage associated with expansion overall or among certain specific population groups. These declines in private coverage may occur if individuals previously covered through employer-sponsored or self-pay insurance opt in to Medicaid given Medicaid’s typically lower out-of-pocket costs and more comprehensive benefit packages, or if employers alter their offering of coverage in response to the expansion of Medicaid. Private coverage changes in studies that include states that expanded later than January 2014 may also reflect people above 100% FPL transitioning from subsidized Marketplace coverage to Medicaid after their state adopts the expansion.248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 256 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 271 272

States implementing the expansion with a waiver have seen similar or larger gains in coverage as states not using waivers, but research finds that some provisions in these waivers present barriers to coverage.

- Studies show that some states initially expanding Medicaid with Section 1115 waivers experienced coverage gains that were similar to gains in states implementing traditional Medicaid expansions. Research comparing Arkansas (which expanded through a premium assistance model) and Kentucky (which expanded through a traditional, non-waiver model) showed no significant differences in uninsured rate declines between 2013 and 2015 in the two states. An analysis of expansion waiver programs in Michigan and Indiana showed that both states experienced uninsured rate reductions between 2013 and 2015 that were higher than the average decrease among expansion states as well as large gains in Medicaid enrollment.273 274 275 276 277 278

- A growing body of research suggests that certain Section 1115 waiver provisions that target the expansion population have caused coverage losses or presented barriers to enrollment, particularly in Arkansas related to the implementation of a Medicaid work requirement and in Indiana related to the Healthy Indiana Plan (HIP) 2.0 monthly contribution requirements.279,280,281 282 283 284 285 286 287 288 289

Impacts on Access and Related Measures

Studies find positive effects of Medicaid expansion on a range of outcomes related to access (Figure 4). In addition to impacts on access to and utilization of care, studies consider the effect of expansion on quality of care, self-reported health, and health outcomes; provider capacity; and affordability and financial security.

Figure 4: Studies find that the ACA Medicaid expansion increased access across a range of measures, though findings on provider capacity are mixed.

Access to Care and Utilization

Most research demonstrates that Medicaid expansion improves access to care and increases utilization of health care services among the low-income population. Many expansion studies point to improvements across a wide range of measures of access to care as well as utilization of a variety of medications and services. Some of this research also shows that improved access to care and utilization is leading to increases in diagnoses of a range of diseases and conditions and in the number of adults receiving consistent care for a chronic condition.290 291 292 293 294 295 296 297 298 299 300 301 302 303 304 305 306 307 308 309 310 311 312 313 314 315 316 317 318 319 320 321 322 323 324 325 326 327 328 329 330 331 332 333 334 335 336 337 338 339 340 341 342 343 344 345 346 347 348 349 350 351 352 353 354 355 356 357 358 359 360 361 362 363 364 365 366 367 368 369 370 371 372 373 374 375 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 384 385 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414 415 416 417 418 419 420 421 422 423

For example:

- Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. Multiple studies found that expansion was associated with significantly greater increases in overall or Medicaid-covered cancer diagnosis rates and/or early-stage diagnosis rates. Multiple studies found an association between expansion and increased access to and utilization of certain types of cancer surgery, with one study finding a decreased disparity in expansion states between Medicaid and privately-insured patients in the odds of undergoing surgery for certain types of cancer.424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432 433 434 435

- Transplants. Additional studies found a correlation between expansion and increased heart transplant listing rates for African American adults (both overall and among Medicaid enrollees) and increased lung transplant listings for nonelderly adults.436 437

- Smoking Cessation. Additional research found decreased cigarette and other nicotine product purchases and increased access, utilization, and Medicaid coverage of evidence-based smoking cessation medications post-expansion in expansion states relative to non-expansion states. For example, one recent study found that Medicaid expansion lead to a 24% increase in new use of smoking cessation medication.438 439 440 441 442 443

- Behavioral Health. Recent evidence demonstrates that Medicaid expansion states have seen improvements in access to medications and services for the treatment of behavioral health (mental health and substance use disorder (SUD)) conditions following expansion, with many national and multi-state studies showing greater improvements in expansion compared to non-expansion states. This evidence includes studies that have shown that Medicaid expansion is associated with increases in overall prescriptions for, Medicaid-covered prescriptions for, and Medicaid spending on medications to treat opioid use disorder and opioid overdose.444 445 446 447 448 449 450 451 452 453 454 455 456 457 458 459 460 461 462 463 464 465 466 467 468 469

- Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. Multiple studies have found increases in medication assisted treatment (MAT) drug prescriptions (either overall or Medicaid-covered prescriptions) associated with expansion. Some of these studies also found that in contrast, there was no increase in opioid prescribing rates (overall or Medicaid-covered) associated with expansion over the same period. One study found that expansion was associated with an 18% increase in aggregate opioid admissions to specialty treatment facilities, nearly all of which was driven by a 113% increase in admissions from Medicaid beneficiaries.470 471 472 473 474 475 476 477 478 479

Multiple recent studies have also found expansion to be associated with improvements in disparities by race/ethnicity, income, education level, insurance type, and employment status in measures of access to and utilization of care.480 481 482 483 484 485 486 487

Studies point to changes in patterns of emergency department (ED) utilization. Some studies point to declines in uninsured ED visits or visit rates and increases in Medicaid-covered ED visits or visit rates in expansion states compared to non-expansion states, compared to pre-expansion, or compared to other populations within expansion states. Studies show inconsistent findings about how Medicaid expansion has affected ED volume or frequency of visits overall or among specific populations (e.g., Medicaid enrollees or frequent ED users), with some studies showing increases, no change, or declines. Studies also showed decreased reliance on the ED as a usual source of care and a shift in ED use toward visits for higher acuity conditions among individual patients who gained expansion coverage, compared to those who remained uninsured in non-expansion states.488 489 490 491 492 493 494 495 496 497 498 499 500 501 502 503 504 505

In contrast with other studies’ findings on decreased reliance on the ED as a usual source of care, some recent studies suggest that Medicaid expansion may increase non-necessary use of certain health services. These services include hospitalization or specialty treatment for certain specific health conditions, including lupus, oral health conditions, and upper-extremity trauma. Authors explain that the non-necessary use of these services could be prevented by primary care and indicates the need for increased access to outpatient care for new enrollees.506 507 508 509

Evidence suggests that beneficiaries and other stakeholders lack understanding of some waiver provisions designed to change utilization or improve health outcomes. Multiple studies have demonstrated confusion among beneficiaries, providers, and advocates in expansion waiver states around the basic elements of the programs or requirements for participation, as well as beneficiary reports of barriers to completion of program activities (including internet access and transportation barriers). These challenges have resulted in increased costs to beneficiaries, beneficiaries being transitioned to more limited benefit packages, low program participation, or programs not operating as intended in other ways.510 511 512 513 514 515 516

Some study findings did not show that expansion significantly improved some measures of access, utilization, or disparities between population groups. Many of these findings were included in studies that also found related improvements in access, utilization, or disparities measures and are also cited above. Authors of some early studies using 2014 data note that changes in utilization may take more than one year to materialize. Consistent with this premise, a longer-term study found improvements in measures of access to care and financial strain in year two of the expansion that were not observed in the first year.517 518 519 520 521 522 523 524 525 526 527 528 529 530 531 532 533 534 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 542 543 544 545 546 547 548 549 550 551 552 553 554 555 556 557 558 559 560 561 562 563 564 565 566 567 568 569 570 571 572 573

Quality of Care, Self-Reported Health, and Health Outcomes

Several studies show an association between Medicaid expansion and improvements in quality of care. These include studies focused on the low-income population broadly, academic medical center or affiliated hospital patients, or community health center patients and look at outcomes including receipt of recommended screenings or recommended care for a particular condition.574 575 576 577 578 579 580 581

Additional studies show effects of expansion on measures of quality hospital care and outcomes. A few studies found that Medicaid expansion was associated with declines in hospital length of stay and in-hospital mortality as well as increases in hospital discharges to rehabilitation facilities, and one study found an association between expansion and declines in mechanical ventilation rates among patients hospitalized for various conditions. One recent study found that expansion was associated with decreased preventable hospitalizations, measured by reductions in annual ambulatory care-sensitive discharge rates and inpatient days. Additional analyses found that, contrary to past studies associating Medicaid insurance with longer hospital stays and higher in-hospital mortality, the shift in payer mix in expansion states (increase in Medicaid discharges and decrease in uninsured discharges) did not influence length of stay or in-hospital mortality for various types of patients.582 583 584,585,586 587 588 589 590 591 592 593 594

Multiple studies have found improvements in measures of self-reported health or positive health behaviors following Medicaid expansions. Studies found improvements in both measures of self-reported physical and mental health, as well as increases in healthy behaviors such as self-reported diabetes management. Additional research has documented provider reports of newly eligible adults showing improved health or receiving life-saving or life-changing treatments that they could not obtain prior to expansion.595 596 597 598 599 600 601 602 603 604 605 606 607 608 609 610 611

Studies have found an association between Medicaid expansion and improvements in certain measures of health outcomes. Studies in this area find an association between expansion and improvements in cardiac surgery patient outcomes and perforated appendix admission rates among hospitalized patients with acute appendicitis. One study did not find a significant association between expansion and differences in rates of low birth weight or preterm birth outcomes overall, but did find significant improvements in relative disparities for black infants compared with white infants in states that expanded vs. those that did not. Two studies found expansion was associated with increased odds of tobacco cessation (among adult CHC patients in one study and childless adults in the other).612 613 614 615 616 617

Additionally, a growing body of research has found an association between Medicaid expansion and mortality, either population-level rates overall, for particular populations, or associated with certain health conditions. A 2019 national study found that expansion was associated with a 0.132 percentage point decline in annual mortality among near-elderly adults driven largely by reductions in disease-related deaths, an effect that translates to about 19,200 deaths that were averted during the first four years of expansion (or 15,600 deaths in expansion states could have been averted in non-expansion states). A 2020 study found that expansion was associated with a 6% lower rate of opioid overdose deaths. Another study suggests that expansion may have contributed to infant mortality rate reductions, finding that the mean infant mortality rate rose slightly in non-expansion states between 2014 and 2016, compared to a decline in expansion states over that period (this effect was particularly pronounced among the African-American population). Studies also found reductions in cardiovascular mortality among middle-aged adults and in one-year mortality among end-stage renal disease patients initiating dialysis.618 619 620 621 622

Some studies did not find significant changes associated with expansion on certain measures of quality of care, self-reported health, or health outcomes.

- Some studies did not find an association between Medicaid expansion and quality outcomes; many of these studies focused on very narrow population groups and/or found a link between expansion and improvements in quality of care for some of the patient/population groups studied. One study found no significant association between Medicaid expansion and changes in quality of care delivered through Medicaid managed care plans. The authors suggest that this finding shows that the health system has generally been able to absorb new expansion enrollees without sacrificing care for existing enrollees.623 624 625 626 627 628 629 630 631 632 633

- Some studies on specific hospital patient groups found no significant changes associated with expansion in measures of hospital care and outcomes, including rates of emergent admission, admissions from clinic, diagnosis category at admission, admission severity, rapid discharges, lengthy hospitalizations, unplanned readmissions, discharges to rehabilitation facilities, or failure to rescue. One study found that expansion was associated with an increase in length of stay for adult trauma patients.634 635 636 637 638 639 640 641 642 643 644 645 646 647 648

- A small number of studies did not find significant changes in certain measures of self-reported health status, health outcomes including mortality, wellbeing, or healthy behaviors, or in disparities between certain population groups in these measures. One study found that although Medicaid expansion was associated with increased access to opioid pain-relievers, it was not significantly associated with any change in opioid deaths. Similarly, an earlier study found no evidence of expansion affecting drug-related overdoses or fatal alcohol poisonings. A third study found that although opioid overdose mortality rates increased more in expansion states, this difference was not caused by increased prescriptions. Given that it may take additional time for measurable changes in health to occur, researchers suggest that further work is needed to provide longer-term insight into expansion’s effects on self-reported health and health outcomes.649 650 651 652 653 654 655 656 657 658 659 660 661 662 663 664 665 666 667 668 669 670 671 672 673

Provider Capacity

Many studies conclude that providers have expanded capacity or participation in Medicaid following expansion and are meeting increased demands for care. Studies in this area include findings showing an association of expansion with increases in primary care appointment availability, the likelihood of accepting new patients with Medicaid among non-psychiatry specialist physicians, and Medicaid acceptance and market entry among select medication assisted treatment (MAT) providers. One study found improvements in receipt of checkups, care for chronic conditions, and quality of care even in areas with primary care shortages, suggesting that insurance expansions can have a positive impact even in areas with relative shortages. A survey of Medicaid managed care organizations found that over seven in ten plans operating in expansion states reported expanding their provider networks between January 2014 and December 2016 to serve the newly-eligible population.674 675 676 677 678 679 680 681 682 683 684 685 686 687 688 689 690 691 692 693 694 695 696 697 698 699 700

Some studies on measures of provider availability showed no changes associated with expansion. Authors note that findings of no changes may, in some cases, be viewed as favorable outcomes indicating that provider availability is not worsening in expansion states despite the increased demand for care associated with expansion. For example, despite concerns that expansion might worsen access for the already-insured, two studies found that expansion was not associated with decreased physician availability for Medicare patients.701 702 703 704 705 706 707 708 709 710 711 712 713 714

Other studies found expansion was linked to problems with provider availability. Some of these studies also had positive or insignificant findings related to provider capacity for certain populations or types of appointment with negative findings related to others. These include findings that Medicaid expansion was associated with longer wait times for appointments or increased difficulty obtaining appointments with specialists. Most of these studies use early data from 2014 and 2015.715 716 717 718 719 720 721 722 723 724 725 726

Affordability and Financial Security

Research suggests that Medicaid expansion improves the affordability of health care. Several studies show that people in expansion states have experienced reductions in unmet medical need because of cost, with national and multi-state studies showing those reductions were greater than reductions in non-expansion states. Research also suggests that Medicaid expansion results in significant reductions in out-of-pocket medical spending, and multiple studies found larger declines in trouble paying as well as worry about paying future medical bills among people in expansion states relative to non-expansion states. A recent study in Washington state found that among trauma patients, expansion was associated with a 12.4 percentage point decrease in estimated catastrophic healthcare expenditure risk. One study found that previously uninsured prescription drug users who gained Medicaid coverage in 2014 saw, on average, a $205 reduction in annual out-of-pocket spending in 2014. A January 2018 study that focused on the 100-138% FPL population in expansion and non-expansion states also found that Medicaid expansion coverage produced greater reductions than subsidized Marketplace coverage in average total out-of-pocket spending, average out-of-pocket premium spending, and average cost-sharing spending.727 728 729 730 731 732 733 734 735 736 737 738 739 740 741 742 743 744 745 746 747 748 749 750 751 752 753 754 755 756 757 758 759 760 761 762 763 764 765 766 767 768 769 770 771 772

- Studies have found that Medicaid expansion significantly reduced the percentage of people with medical debt, reduced the average size of medical debt, and reduced the probability of having one or more medical bills go to collections in the past 6 months.773 774 775 776 777 778 779 780 781 782 783

- A study in Ohio showed lower medical debt holding levels among continuously-enrolled expansion enrollees compared to those who unenrolled from expansion and those who had a coverage gap, suggesting that medical debt levels rose even after a relatively short time without Medicaid expansion coverage.784 785

Research also suggests an association between Medicaid expansion and improvements in broader measures of financial stability.786 787 788 789 790 791 792 793 794

For example:

- A study found that Medicaid expansion was associated with a 2.2 percentage point decrease in very low food security (which is characterized by actual reduction of food intake due to unaffordability) among low-income childless adults.795

- Two 2019 national studies looked at the association between Medicaid expansion and poverty rates. One found that expansion was associated with a reduction in the rate of poverty by just under 1 percentage point (or an estimated 690,000 fewer Americans living in poverty). The other found that Medicaid expansion was associated with a 1.7 percentage point reduction in the health-inclusive poverty measure (HIPM) poverty rate and a 0.9 percentage point reduction in the HIPM deep poverty rate that were significant across all demographic groups considered except single-parent households and were particularly substantial for vulnerable groups including children, the near-elderly (age 55-64), black people, Hispanics, and those who have not completed high school. The same study showed no significant change in the Census Bureau’s supplemental poverty measure (SPM).796 797

- Studies have found that Medicaid expansion significantly reduced the average number of collections, improved credit scores, reduced over limit credit card spending, reduced public records (such as evictions, bankruptcies, or wage garnishments), and reduced the probability of a new bankruptcy filing, among other improvements in measures of financial security. One 2019 study found that Medicaid expansion was associated with a 1.15 reduction in the rate of evictions per 1000 renter-occupied households and a 1.59 reduction in the rate of eviction filings.798 799 800 801 802 803

- A Michigan study found an association between expansion and improvements across a broad swath of financial measures.804

Multiple studies have found expansion to be associated with improvements in disparities by income or race/ethnicity in measures of affordability of care or financial security.805 806 807 808 809 810

Some study findings did not show significant effects of expansion on measures of affordability or financial security. Several of these studies did not identify statistically significant differences in changes in unmet medical need due to cost between expansion and non-expansion states, though authors note that some of these findings may have been affected by study design or data limitations. Other studies did not find changes associated with expansion in trouble or worry about paying medical bills. Two studies did not find improvements in disparities by race/ethnicity associated with expansion in measures of unmet care needs due to cost.811 812 813 814 815 816 817 818 819 820 821 822 823 824 825 826 827 828 829 830 831

Economic Effects

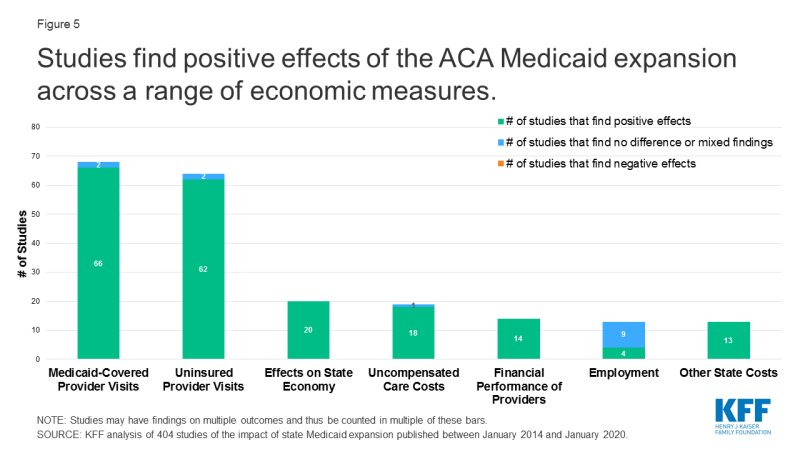

Studies find positive effects of Medicaid expansion on a range of economic measures (Figure 5). Economic effects of expansion include changes to payer mix and other impacts on hospitals and other providers; effects on state budgets and economies; Medicaid spending per enrollee; marketplace effects; and employment and labor market effects.

Figure 5: Studies find positive effects of the ACA Medicaid expansion across a range of economic measures.

State Budgets and Economies

Analyses find effects of expansion on multiple state economic outcomes, including budget savings, revenue gains, and overall economic growth. These positive effects occurred despite Medicaid enrollment growth initially exceeding projections in many states and increases in total Medicaid spending, largely driven by increases in federal spending given the enhanced federal match rate for expansion population costs provided under the ACA (the federal share was 100% for 2014-2016). As of Summer 2019, most expansion states reported relying on general fund support to finance the state share of expansion costs, although some also use new or increased provider taxes/fees or savings accrued as a result of the expansion. While studies showed higher growth rates in total Medicaid spending (federal, state, and local) following initial expansion implementation in 2014 and 2015 compared to the previous few years, this growth rate slowed significantly beginning in 2016. There is limited research examining the fiscal effects at the federal level from the additional expenditures for the Medicaid expansion or the revenues to support that spending.832 833 834 835 836 837 838 839 840 841 842 843 844 845 846 847 848 849 850 851 852 853 854

- National research found that there were no significant increases in spending from state funds as a result of Medicaid expansion and no significant reductions in state spending on education, transportation, or other state programs as a result of expansion during FYs 2010-2015. During this period, the federal government paid for 100% of the cost expansion. State spending could rise as the federal matching for the expansion phases down to 90%.855

- Single-state studies in Louisiana and Montana showed that expansion resulted in large infusions of federal funds into the states’ economies and significant state savings. Louisiana studies showed increases in overall state and local tax receipts in 2017 and 2018. A study in Montana found positive financial effects for businesses due to infusion of federal dollars to fund health coverage for workers.856 857 858 859 860

Multiple studies suggest that Medicaid expansion resulted in state savings by offsetting state costs in other areas, including state costs related to behavioral health services and crime and the criminal justice system. For example, a study in Montana showed offsets for state SUD spending, a study in California showed reduced county safety-net spending, and a study in Michigan pointed to state savings for non-Medicaid health programs (including the state’s community mental health system, its Adult Benefit Waiver program, and spending on health care for prisoners), which, combined with increased tax revenue associated with expansion, resulted in net fiscal benefits expected through 2021. Limited research also indicates possible federal and state savings due to decreased SSI participation associated with expansion.861 862 863 864 865 866 867 868 869 870 871 872 873 874 875

Medicaid Spending Per Enrollee

Studies have found lower Medicaid spending per enrollee for the new ACA adult eligibility group compared to traditional Medicaid enrollees (including seniors and people with disabilities in some studies and excluding those populations in others) and that per enrollee costs for newly eligible adults have declined over time since initial implementation of the expansion.876 877 878 879 880 881 882 883

- One analysis found that in 2014, among those states reporting both spending and enrollment data, spending per enrollee for the new adult group was much lower than spending per enrollee for traditional Medicaid enrollees. Similarly, an analysis of 2012-2014 data from expansion states found that average monthly expenditures for newly eligible Medicaid enrollees were $180, 21% less than the $228 average for previously eligible enrollees.884 885

- A June 2017 study showed that per enrollee Medicaid spending declined in expansion states

(-5.1%) but increased in non-expansion states (5.1%) between 2013 and 2014. Researchers attributed these trends to the ACA Medicaid expansion, which increased the share of relatively less expensive enrollees in the Medicaid beneficiary population mix in expansion states.886

Marketplace Effects

Studies suggest that Medicaid expansion supports the ACA Marketplaces and may help to lower Marketplace premiums. Two national studies showed that Marketplace premiums were significantly lower in expansion compared to non-expansion states, with estimates ranging from 7% lower in 2015 to 11-12% lower in a later study that looked at 2015-2018 data. Another study found that the state average plan liability risk score was higher in non-expansion than expansion states in 2015 (higher risk scores are associated with sicker state risk pools and likely translate to higher premiums). A study in Arkansas showed that the “private option” expansion has helped to boost the number of carriers offering Marketplace plans statewide, generated a younger and relatively healthy risk pool in the Marketplace, and contributed to a 2% drop in the average rate of Marketplace premiums between 2014 and 2015. A study of New Hampshire’s Premium Assistance Program (PAP) population (Medicaid expansion population enrolled in the Marketplace), however, showed higher medical costs for the PAP population compared to other Marketplace enrollees.887 888 889 890 891

Impacts on Hospitals and Other Providers

Research shows that Medicaid expansions result in reductions in uninsured hospital, clinic, or other provider visits and uncompensated care costs, whereas providers in non-expansion states have experienced little or no decline in uninsured visits and uncompensated care. One study suggested that Medicaid expansion cut every dollar that a hospital in an expansion state spent on uncompensated care by 41 cents between 2013 and 2015, corresponding to a reduction in uncompensated care costs across all expansion states of $6.2 billion over that period.892 893 894 895 896 897 898 899 900 901 902 903 904 905 906 907 908 909 910 911 912 913 914 915 916 917 918 919 920 921 922 923 924 925 926 927 928 929 930 931 932 933 934 935 936 937 938 939 940 941 942 943 944 945 946 947 948 949 950 951 952 953 954 955 956 957 958 959 960 961 962 963 964 965 966 967 968 969 970 971 972 973 974 975

- Some studies point to changes in payer mix within emergency departments (EDs), specifically. Multiple studies found significant declines in uninsured ED visits and increases in Medicaid-covered ED visits following expansion implementation. In addition, one study found that expansion was associated with a 6.3% increase in ED physician reimbursement per visit in states that newly expanded coverage for adults from 0% to 138% FPL compared to non-expansion states.976 977 978 979 980 981 982 983 984 985 986 987 988 989

- Multiple studies found an association between expansion and significant increases in Medicaid coverage of patients/treatment at specialty substance use disorder (SUD) treatment facilities or treatment programs, with two studies also showing associated decreases in the probability that patients at these facilities were uninsured. An additional study found large shifts in sources of payment for SUD treatment among justice-involved individuals following Medicaid expansion in 2014, with significant increases in those reporting Medicaid as the source of payment.990 991 992 993 994

- Numerous recent studies found an association between expansion and payer mix (decreases in uninsured patients and increases in Medicaid patients) among patients hospitalized for certain specific conditions, including a range of cardiovascular conditions and operations; diabetes-related conditions; traumatic injury; and cancer surgery. Another analysis found expansion was associated with increases in Medicaid patient admissions for five of the eight types of cancer included in the study. Additional studies found that expansion was associated with increases in the proportion of transplant listings (for lung, liver, and pre-emptive kidney transplants, especially among racial and ethnic minorities) with Medicaid coverage, as well as increases in the proportion of received pre-emptive kidney transplantations that were covered by Medicaid. Two additional studies also found an increase in the chances of enrolling in Medicaid during post-liver transplant care. A study using birth certificate data found that expansion was associated with an increased proportion of deliveries covered by Medicaid, which was offset by a decrease in the proportion covered by private insurers or other payers but no change in the proportion of women who were uninsured.995 996 997 998 999 1000 1001 1002 1003 1004 1005 1006 1007 1008 1009 1010 1011 1012 1013 1014 1015 1016 1017

- Studies found that expansion’s impact on payer mix and uncompensated care varied by the type and location of hospital. Two studies found larger decreases in uncompensated care and increases in Medicaid revenue among hospitals that treat a disproportionate share of low-income patients (DSH hospitals) compared to those that do not. A third study found no significant association of Medicaid expansion with changes in charge-to-cost ratio for certain surgical procedures in safety net hospitals vs. non-safety net hospitals, suggesting that safety net hospitals did not increase charges to private payers in response to expansion-related payer mix changes. A fourth study found that Medicaid expansion was significantly associated with increased Medicaid-covered discharges for rural hospitals but not for urban hospitals, but that urban hospitals saw significant reductions in uncompensated care costs while rural hospitals did not.1018 1019 1020 1021

Additional studies demonstrate that Medicaid expansion has significantly improved operating margins and financial performances for hospitals, other providers, and managed care organizations. A study published in January 2018 found that Medicaid expansion was associated with improved hospital financial performance and significant reductions in the probability of hospital closure, especially in rural areas and areas with higher pre-ACA uninsured rates. Another analysis found that expansion’s effects on margins were strongest for small hospitals, for-profit and non-federal-government-operated hospitals, and hospitals located in non-metropolitan areas. A third study found larger expansion-related improvements in operating margins for public (compared to nonprofit or for-profit) hospitals and rural (compared to non-rural) hospitals.1022 1023 1024 1025 1026 1027 1028 1029 1030 1031 1032 1033 1034

- A study of Ascension Health hospitals nationwide found that the decrease in uncompensated care costs for hospitals in expansion states was greater than the increase in Medicaid shortfalls between 2013 and 2014, whereas for hospitals in non-expansion states, the increase in Medicaid shortfalls exceeded the decrease in uncompensated care.1035

- A survey of Medicaid managed care organizations found that nearly two-thirds of plans in expansion states reported that the expansion has had a positive effect on their financial performance.1036

- Recent studies on the association between expansion and hospital costs or charges for specific conditions have found mixed results. One study found expansion was associated with increased diagnosis-related group charges for lupus hospitalizations, but another study found an association between expansion and reduced hospital costs for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions and a third found lower total index hospital charges within the homeless population in expansion states. An additional study found that hospital costs for minimally-invasive surgical care decreased for Medicaid-insured patients in expansion states, but increased for uninsured/self-pay patients.1037 1038 1039 1040

Some research suggests that savings to providers following expansion may be partially offset by increases in Medicaid shortfalls (the difference between what Medicaid pays and the cost of care for Medicaid patients). One recent study found that while expansion led to substantial reductions in hospitals’ uncompensated care costs, savings were offset somewhat by increased Medicaid payment shortfalls (increases were greater in expansion relative to non-expansion states).1041

Employment and Labor Market Effects

State-specific studies have documented significant job growth resulting from expansion. Studies in Louisiana found that in FY 2017, the injection of federal expansion funds created and supported 19,195 jobs (while creating and supporting personal earnings of $1.12 billion) in sectors throughout the economy and across the state; in FY 2018, continued federal healthcare spending supported 14,263 jobs and $889.0 million in personal earnings. A study in Colorado found that the state supported 31,074 additional jobs due to Medicaid expansion as of FY 2015-2016.1042 1043 1044 1045 1046

Some studies found expansion was linked to increased employment. National research found increases in the share of individuals with disabilities reporting employment and decreases in the share reporting not working due to a disability in Medicaid expansion states following expansion implementation, with no corresponding trends observed in non-expansion states; other research found a decline in participation in Supplemental Security Income, which requires people to demonstrate having a work-limiting disability and limits their allowable earned income. Another national study found evidence that for many of the demographic groups included in the analysis, expansion was associated with an increase in labor force participation and employment. The study also found a significant decrease in involuntary part-time work for both the full population sample and the sample of those with incomes at or below 138% FPL. A multi-state study found that by the fourth year of expansion, growth in total employment was 1.3 percentage points higher and employment growth in the health care sector was 3.2 percentage points higher in the expansion states studied than in non-expansion states.1047 1048 1049 1050 1051 1052

Multiple studies showed that expansion supported enrollees’ ability to work, seek work, or volunteer. Single-state studies in Ohio and Michigan showed that large percentages of expansion beneficiaries reported that Medicaid enrollment made it easier to seek employment (among those who were unemployed but looking for work) or continue working (among those who were employed). The Michigan study found that 69% of enrollees who were working said they performed better at work once they got expansion coverage. Another study found that 46% of primary care physicians surveyed in Michigan reported that Michigan’s Medicaid expansion had a positive impact on patients’ ability to work. An additional study in Michigan found that enrollees who reported improved health due to expansion were more likely to say that expansion coverage improved their ability to work and to seek a new job. In addition, a national study found an association between Medicaid expansion and volunteer work (both formal volunteering for organizations and informally helping a neighbor), with significant increases in volunteer work occurring among low-income individuals in expansion states in the post-expansion period (through 2015) but no corresponding increase in non-expansion states. The researchers connect this finding to previous literature showing an association between improvements in individual health and household financial stabilization and an increased likelihood of volunteering.1053 1054 1055 1056 1057

Some studies found no effects of expansion on some measures of employment or employee behavior; just one study found a negative effect of expansion on these measures. Measures in this area that showed no changes related to expansion in some studies include measures of employment rates, transitions from employment to non-employment, the rate of job switches, transitions from full- to part-time employment, labor force participation, usual hours worked per week, self-employment, and Supplemental Security Income applications. Authors of two studies note that expansion had no effect on employment and job-seeking despite concerns that the availability of free non-employer health insurance could be a disincentive to finding employment. A 2019 study comparing pairs of bordering counties in expansion and non-expansion states found that expansion was associated with a temporary 1.2% decrease in employment one year after implementation (although this effect did not persist two years after expansion) and no effect on wages at any point.1058 1059 1060 1061 1062 1063 1064 1065 1066 1067

Emerging Studies

Medicaid expansion was associated with a statistically significant decrease in reported cases of neglect for children younger than six years, but no significant change in rates of physical abuse for children under six. Another 2019 study found that Medicaid expansion was associated with increased undercounting of Medicaid enrollment in the American Community Survey. A 2017 study found that expansion was negatively associated with the prevalence of divorce among those ages 50-64 and infers that this likely indicates a reduction in medical divorce. A study found that expansion was not associated with increased migration from non-expansion states to expansion states in 2014, indicating that individuals did not migrate in order to gain access to Medicaid benefits. An additional group of studies suggests that Medicaid expansion may have significant effects on measures related to individuals’ political activity and views. Specifically, studies show associations between Medicaid expansion and increases in voter registration, ACA favorability, and gubernatorial approval. One study found that the increase in Medicaid enrollment following Medicaid expansion was associated with increases in voter turnout for U.S. House races in 2014 compared to 2012 (i.e., a reduction in the size of the usual midterm drop-off in turnout), but another study showed only weak evidence of a potential turnout effect of expansion in the 2014 election, and a consistent lack of any impact on turnout in 2016.1068 1069 1070 10711072 1073 1074 1075 1076

The authors thank Larisa Antonisse for her work on previous versions of this brief and assistance with reviewing recently published studies included in this update, as well as Eva Allen from The Urban Institute for her assistance with reviewing studies first included in an earlier version of this brief.