States Respond to COVID-19 Challenges but Also Take Advantage of New Opportunities to Address Long-Standing Issues

Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2021 and 2022

Executive Summary

The coronavirus pandemic has generated both a public health crisis and an economic crisis, with major implications for Medicaid—a countercyclical program—and its beneficiaries. The pandemic has profoundly affected Medicaid program spending, enrollment, and policy, challenging state Medicaid agencies, providers, and enrollees in a variety of ways.1 As states continue to respond to pandemic challenges, they are also pushing forward non-emergency initiatives as well as preparing for the unwinding of the public health emergency (PHE) and the return to a new normal of operations. The current PHE declaration expires on January 16, 2022,2 though the Biden Administration could renew the declaration again and has notified states that it will provide 60 days of notice prior to the declaration’s termination or expiration.3 The duration of the PHE will affect a range of emergency policy options4 in place as well as a 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal match rate (“FMAP”)5 (retroactive to January 1, 2020) available if states meet certain “maintenance of eligibility”6 requirements included in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA).7

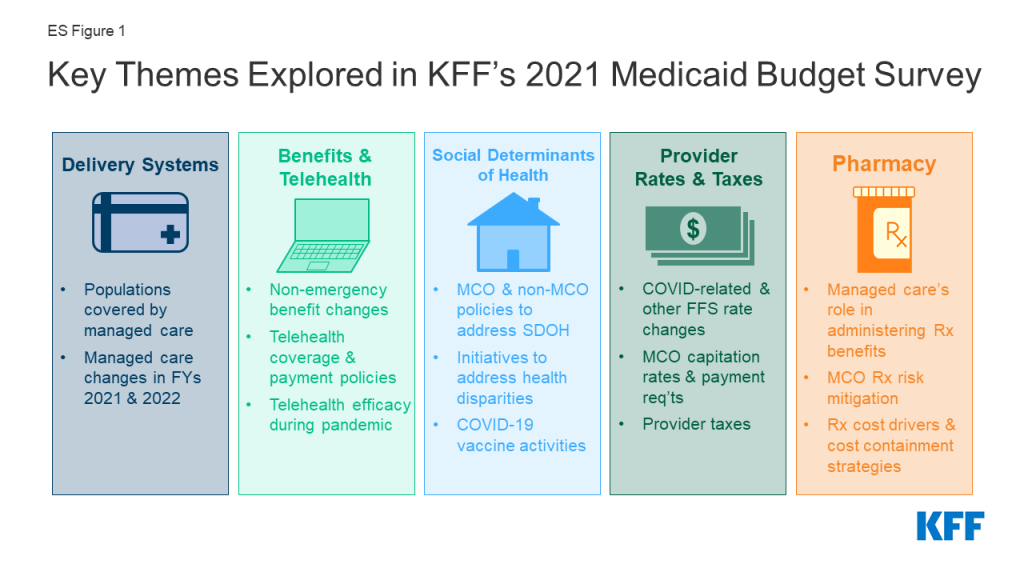

This report highlights certain policies in place in state Medicaid programs in state fiscal year (FY) 2021 and policy changes implemented or planned for FY 2022, which began on July 1, 2021 for most states;8 we also highlight state experiences with policies adopted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings are drawn from the 21st annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and Health Management Associates (HMA), in collaboration with the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD). States completed this survey in mid-summer of 2021, following increased vaccination rates and declining COVID-19 cases but just prior to a new wave of COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths driven by the highly contagious Delta variant. Overall, 47 states responded to this year’s survey, although response rates for specific questions varied.9 This report summarizes key findings across five sections: delivery systems, benefits and telehealth, social determinants of health (which also includes information on health equity and COVID-19 vaccine uptake), provider rates and taxes, and pharmacy (ES Figure 1).

Delivery Systems

The vast majority of states that contract with managed care organizations (MCOs) reported that 75% or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs as of July 1, 2021.10 Children and adults (particularly expansion adults) are much more likely to be enrolled in an MCO than elderly or individuals with disabilities. MCOs provide comprehensive acute care (i.e., most physician and hospital services) and in some cases long-term services and supports (LTSS) to Medicaid beneficiaries. MCOs are at financial risk for the services covered under their contracts and receive a per member per month “capitation” payment for these services.11 Enrollment in Medicaid MCOs has grown12 since the start of the pandemic, tracking with overall growth in Medicaid enrollment.13 Throughout other sections of this survey, we report state policy changes that often apply to both the managed care and/or fee-for-service (FFS) delivery systems.

Benefits and Telehealth

The number of states reporting new benefits and benefit enhancements in FY 2021 and FY 2022 greatly outpaced the number of states reporting benefit cuts and limitations. While state benefit actions are often influenced by prevailing economic conditions,14 when the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic downturn hit, instead of restricting benefits, most states used Medicaid emergency authorities to temporarily adopt new benefits, adjust existing benefits, and/or waive prior authorization requirements.15 States may choose to permanently extend these emergency benefit changes past the PHE period. Many states are now focused on expanding behavioral health services, care for pregnant and postpartum women, dental benefits, and housing-related supports.

An overwhelming majority of states noted the benefits of telehealth in maintaining or expanding access to care during the pandemic, particularly for behavioral health services. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many states expanded Medicaid telehealth coverage, including through the use of Medicaid emergency authorities.16 Preliminary CMS data shows that utilization of telehealth in Medicaid and CHIP has dramatically increased during the pandemic; however, telehealth access is not equally available to all Medicaid enrollees.17 Nearly all responding states report covering a range of services via audio-visual telehealth as of July 2021, with slightly fewer states reporting audio-only coverage. All or nearly all responding states at least sometimes cover audio-visual delivery of behavioral health, reproductive health, and well/sick child services, with fewer states reporting audio-visual coverage of HCBS and dental services. Trends in telehealth utilization during the pandemic vary across states. Post-pandemic telehealth coverage and reimbursement policies are being evaluated in most states, with states weighing expanded access against quality concerns, especially for audio-only telehealth.

Social Determinants of Health

Most states reported that the COVID-19 pandemic prompted them to expand Medicaid programs to address social determinants of health, especially related to housing. States also report existing initiatives in this area in MCO contracts (e.g., requirements for MCOs to screen and refer enrollees for social needs). Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age that shape health.18 In response to the pandemic, federal legislation has been enacted to provide significant new funding to address the health and economic effects of the pandemic including direct support to address food and housing insecurity as well as stimulus payments to individuals, federal unemployment insurance payments, and expanded child tax credit payments. While measures like these have a direct impact in helping to address SDOH, health programs like Medicaid can also play a supporting role. Although federal Medicaid rules prohibit expenditures for most non-medical services, state Medicaid programs have been developing strategies to identify and address enrollee social needs both within and outside of managed care.

Three-quarters of responding states reported initiatives to address disparities in health care by race/ethnicity in Medicaid, with many focusing on specific health outcomes including maternal and infant health, behavioral health, and COVID-19 outcomes and vaccination rates. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated already existing health disparities for a broad range of populations, but specifically for people of color.19 Multiple analyses of available federal, state, and local data show that people of color are experiencing a disproportionate burden of COVID-19 cases and deaths. In addition to worse health outcomes, data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey show that during the pandemic, Black and Hispanic adults have fared worse than White adults across nearly all measures of economic and food security.20

States report a variety of MCO activities aimed at promoting the take-up of COVID-19 vaccinations. These include member and provider incentives, member outreach and education, provider engagement, assistance with vaccination scheduling and transportation coordination, and partnerships with state and local organizations. Given the large number of people covered by Medicaid, including groups disproportionately at risk of contracting COVID-19 as well as many individuals facing access challenges, state Medicaid programs and Medicaid MCOs (which enroll over two-thirds of all Medicaid beneficiaries)21 can be important partners in COVID-19 vaccination efforts.22

Provider Rates and Taxes

Reported FFS rate increases outnumber rate restrictions in both FY 2021 and FY 2022, with more than two-thirds of states indicating payment changes related to COVID-19. The most common COVID-19-related payment changes were rate increases for nursing facilities and home and community-based services (HCBS) providers. Although states historically are more likely to restrict rates during economic downturns, states likely found rate reductions to be less feasible as many providers faced financial strain from the increased costs of COVID-19 testing and treatment or from declining utilization of non-urgent care, especially in the early months of the pandemic.23 Starting early in the pandemic, Congress, states,24 and the Administration adopted a number of policies to ease financial pressure on hospitals and other health care providers.25

Among states that implemented COVID-19-related risk corridors in 2020 or 2021 MCO contracts, about half reported that they have or will recoup funds, while recoupment in the remaining states remains undetermined. Although state capitation payments to MCOs (and prepaid health plans, known as PHPs) must be actuarially sound,26 states use a variety of mechanisms (including risk corridors) to adjust managed care plan risk, incentivize performance, and ensure plan payments are not too high or too low.27 While most states rely on capitated arrangements with comprehensive MCOs to deliver Medicaid services to most of their Medicaid populations, state-determined FFS rates remain important benchmarks for MCO payments in many states, often serving as the state-mandated payment floor. About two-thirds of responding states with managed care plans (MCOs or PHPs) reported minimum fee schedule requirements that set a reimbursement floor for one or more specified provider types.

Pharmacy

A majority of responding states reported prohibiting spread pricing in MCO subcontracts with their pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), which reflects a significant increase in state Medicaid agency oversight of MCO subcontracts with PBMs compared to previous surveys. The administration of the Medicaid pharmacy benefit has evolved over time to include delivery of these benefits through MCOs and increased reliance on PBMs.28 PBMs may perform a variety of administrative and clinical services for Medicaid programs (e.g., negotiating rebates with drug manufacturers, adjudicating claims, monitoring utilization, overseeing preferred drug lists (PDLs) etc.) and are used in FFS and managed care settings. MCO subcontracts with PBMs are under increasing scrutiny as more states recognize a need for transparency and stringent oversight of these subcontract arrangements.

More than half of states reported newly implementing or expanding at least one initiative to contain prescription drug costs in FY 2021 and/or FY 2022. While Medicaid net spending on prescription drugs remained almost unchanged from 2015 to 2019, spending before rebates increased, likely reflecting the launch of expensive new brand drugs and increasing list prices.29 As a result, state policymakers remain concerned about Medicaid prescription drug spending growth and the entry of new high-cost drugs to the market. States continuously innovate to address these pressures with cost containment strategies and utilization controls that include but are not limited to PDLs, managed care pharmacy carve-outs, and multi-state purchasing pools. A number of states also report laying the groundwork to employ value-based arrangements (VBA) with pharmaceutical manufacturers as a way to control pharmacy costs.

Looking Ahead

States completed this survey in mid-summer of 2021, following increased vaccination rates and declining COVID-19 cases but just prior to a new wave of COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths driven by the highly contagious Delta variant. At that time, states continued to focus on ongoing pandemic-related challenges for agencies, providers, and enrollees, but were also looking ahead to prepare for challenges associated with the unwinding of the PHE. Despite the upheaval caused by the pandemic, states also continued to advance non-emergency priority initiatives and to maintain efficient and effective program operations.

State officials also pointed to lessons learned during the pandemic that may provide opportunities to strengthen relationships with providers, develop new relationships with other community stakeholders, and improve enrollee access and outcomes during and beyond the PHE transition period. States identified ongoing efforts to advance delivery system reforms and to address health disparities and social determinants of health as areas of promise to build on in the future. Looking ahead, uncertainty remains regarding the future course of the pandemic and what kind of “new normal” states can expect in terms of service provision and demand as well as challenges associated with the unwinding of the PHE. In addition, as part of budget reconciliation, Congress is currently considering additional Medicaid policies building on earlier legislation to expand coverage and increase HCBS funding, which could have further implications for the direction of Medicaid policy in the years ahead. Finally, states may pursue and CMS under the Biden administration may promote Section 1115 demonstration waivers to help improve social determinants of health and advance health equity.30

Acknowledgements

Pulling together this report is a substantial effort, and the final product represents contributions from many people. The combined analytic team from KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) would like to thank the state Medicaid directors and staff who participated in this effort. In a time of limited resources and challenging workloads, we truly appreciate the time and effort provided by these dedicated public servants to complete the survey and respond to our follow-up questions. Their work made this report possible. We also thank the leadership and staff at the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD) for their collaboration on this survey. We offer special thanks to Jim McEvoy and Kraig Gazley at HMA who developed and managed the survey database and whose work is invaluable to us; and to Meghana Ammula at KFF who assisted with review of data and text.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and public health emergency (PHE) declaration dramatically impacted state Medicaid programs, requiring states to rapidly adapt to meet the changing needs of Medicaid enrollees and providers. Nationwide, Medicaid provided health insurance coverage to nearly one in five Americans in 202031 and accounted for nearly one-sixth of all U.S. health care expenditures in 2019.32 Total Medicaid/CHIP enrollment grew to 82.3 million in April 2021, an increase of 11.1 million (15.5%) from February 2020, right before the pandemic and when enrollment began to steadily increase.33

Beginning early in the pandemic, states and the federal government implemented numerous Medicaid emergency authorities to enhance state capacity to respond to the emerging public health and economic crises.34 In addition, Congress authorized changes to Medicaid through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA)35 and Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act,36 including a 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal Medicaid match rate (“FMAP”) (retroactive to January 1, 2020). This “enhanced FMAP” is available to states that meet “maintenance of eligibility” (MOE) conditions which ensure continued coverage for current enrollees as well as coverage of coronavirus testing and treatment.37 All of these changes (the emergency policy actions, the fiscal relief and the MOE) are tied to the duration of the PHE. The current PHE declaration expires on January 16, 2022,38 though the Biden Administration could renew the declaration again and has notified states that it will provide 60 days of notice prior to the declaration’s termination or expiration.39 The Biden Administration also recently updated previous state guidance regarding the end of the PHE and transition to normal operations,40 allowing states additional time to complete renewals and redeterminations once the PHE ends.41

This report draws upon findings from the 21st annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA), in collaboration with the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD). (Previous reports are archived here.42 ) This year’s KFF/HMA Medicaid budget survey was conducted via a survey sent to each state Medicaid director in June 2021 and then a follow-up telephone interview. Overall, 47 states responded in summer of 2021,43 although response rates for specific questions varied. The District of Columbia is counted as a state for the purposes of this report. Given differences in the financing structure of their programs, the U.S. territories were not included in this analysis. The survey instrument is included as an appendix to this report.

This report examines Medicaid policies in place or implemented in state fiscal year (FY) 2021, policy changes implemented at the beginning of FY 2022, and policy changes for which a definite decision has been made to implement in FY 2022 (which began for most states on July 1).44 We also examine state experiences with policies adopted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Policies adopted for the upcoming year are occasionally delayed or not implemented for reasons related to legal, fiscal, administrative, systems, or political considerations, or due to CMS approval delays. States completed this survey in mid-summer of 2021, following increased vaccination rates and declining COVID-19 cases but just prior to a new wave of COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths driven by the highly contagious Delta variant. Key findings, along with state-by-state tables, are included in the following sections:

- Delivery Systems

- Benefits and Telehealth

- Social Determinants of Health (also includes information on health equity and COVID-19 vaccine uptake)

- Provider Rates and Taxes

- Pharmacy

- Challenges and Priorities in FY 2022 and Beyond Reported by Medicaid Directors

Delivery Systems

Context

For more than two decades, states have increased their reliance on managed care delivery systems often with broad goals to improve access and outcomes, enhance care management and care coordination, and better control costs.45 State managed care contracts vary widely, for example, in the populations required to enroll, the services covered (or “carved in”), and the quality and performance incentives and penalties provided. In general, most states contract with risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs) that cover a comprehensive set of benefits (acute care services and sometimes long-term services and supports), but many also contract with limited benefit prepaid health plans (PHPs) that offer a narrow set of services such as dental care, nonemergency medical transportation, or behavioral health services. A minority of states operate primary care case management (PCCM) programs which retain fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursements to providers, but enroll beneficiaries with a primary care provider who is paid a small monthly fee to provide case management services in addition to primary care.

MCOs are at financial risk for the services covered under their contracts and receive a per member per month “capitation” payment for these services.46 (The Provider Rates and Taxes section of this report includes information on state options to address MCO payment issues in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.) Enrollment in Medicaid MCOs has grown since the start of the pandemic, tracking with overall growth in Medicaid enrollment.47

This section provides information about:

- Managed care models;

- Populations covered by risk-based managed care; and

- Managed care changes

Findings

Managed Care models

Capitated managed care remains the predominant delivery system for Medicaid in most states. As of July 2021, all states except four – Alaska, Connecticut,48 Vermont,49 and Wyoming – had some form of managed care (MCOs and/or PCCMs) in place. As of July 2021, 41 states50 were contracting with MCOs, up from 40 states in 2019 (with the addition of North Carolina), and only two of these states (Colorado and Nevada) did not offer MCOs statewide. Twelve states reported operating a PCCM program, unchanged from 2019.51

Of the 47 states that operate some form of managed care, 35 states operate MCOs only,52 six states operate PCCM programs only,53 and six states operate both MCOs and a PCCM program (Figure 1 and Table 1). In total, 27 states54 were contracting with one or more PHPs to provide Medicaid benefits including behavioral health care, dental care, vision care, non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT), long-term services and supports (LTSS).

Populations Covered by Risk-Based Managed Care

The vast majority of states that contract with MCOs (36 of 41) reported that 75% or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs as of July 1, 2021. This is an increase of three states compared to the 2019 survey and includes the ten states with the largest total Medicaid enrollment (Figure 2 and Table 1). These ten states account for over half of all Medicaid beneficiaries across the country.55

Children and adults, particularly those enrolled through the ACA Medicaid expansion, are much more likely to be enrolled in an MCO than elderly Medicaid beneficiaries or persons with disabilities. Thirty-seven of the 41 MCO states reported covering 75% or more of all children through MCOs. Of the 38 states56 that had implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion as of July 1, 2021, 31 were using MCOs to cover newly eligible adults. The large majority of these states (28 states) covered more than 75% of beneficiaries in this group through capitated managed care. Thirty-four of the 41 MCO states reported covering 75% or more of low-income adults in pre-ACA expansion groups (e.g., parents, pregnant women) through MCOs. In contrast, the elderly and people with disabilities were the group least likely to be covered through managed care contracts, with only 19 of the 41 MCO states reporting coverage of 75% or more such enrollees through MCOs (Figure 2).

Managed Care Changes

A number of states reported a variety of managed care changes made in state fiscal year (FY) 2021 or planned for FY 2022. Notable changes included the following:

- North Carolina reported implementing its first MCO program. On July 1, 2021, North Carolina launched new MCO “Standard Plans,” offering integrated physical and behavioral health services statewide, with mandatory enrollment for most population groups (nearly 1.6 million enrollees).

- Four states (Arizona, Illinois, Kentucky, and New York) reported managed care changes for children in foster care. Arizona established a fully integrated managed care plan for children in state custody in April 2021; Illinois transitioned youth in care of the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services into the YouthCare Health Plan in September 2020; Kentucky awarded one MCO a contract to manage and oversee Medicaid services for children enrolled in foster care in FY 2021; and New York began mandatory MCO enrollment of children and youth in direct placement foster care in New York City and children and youth placed in foster care in the care of Voluntary Foster Care Agencies statewide in July 2021.

- Two states (District of Columbia and Tennessee) reported expanding mandatory MCO enrollment for other targeted populations. The District of Columbia expanded mandatory managed care enrollment in FY 2021 to include beneficiaries receiving Medicaid Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or SSI-related Medicaid because of a disability, and Tennessee intends to integrate intermediate care facility services for individuals with intellectual disabilities and home and community-based services (HCBS) for persons with intellectual disabilities into its statewide managed care program in FY 2022.

- Three states (Maine, North Carolina, and Oregon) reported changes to their PCCM programs. North Carolina launched a new PCCM option in July 2021 available only to Indian Health Service (IHS) eligible beneficiaries associated with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in select counties in the western part of the state; Oregon reported plans to implement an Indian PCCM program in FY 2022; and Maine reported plans to end its PCCM program in FY 2022 and replace it with a value-based payment model designed to simplify, integrate, and improve the state’s current primary care programs.57 ,58

- Texas ended its non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) PHP program and carved NEMT services into its MCO contracts effective June 1, 2021.

- Illinois expanded its Medicare-Medicaid Alignment Initiative statewide on July 1, 2021. This initiative allows eligible beneficiaries to receive their Medicare Parts A and B benefits, Medicare Part D benefits, and Medicaid benefits from a single Medicare-Medicaid MCO.

Benefits and Telehealth

Context

State Medicaid programs are statutorily required to cover a core set of “mandatory” benefits, but may choose whether to cover a broad range of optional benefits.59 States may apply reasonable service limits based on medical necessity or to control utilization, but once covered, services must be “sufficient in amount, duration and scope to reasonably achieve their purpose.”60 State benefit actions are often influenced by prevailing economic conditions: states are more likely to adopt restrictions during downturns and expand or restore benefits as conditions improve.61 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic,62 trends in state changes to Medicaid benefits included enhancements of behavioral health services as well as efforts to advance maternal and infant health.63 When the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic downturn hit, instead of restricting benefits, most states used Medicaid emergency authorities64 to temporarily adopt new benefits, adjust existing benefits, and/or waive prior authorization requirements, and in 2020,65 some states indicated plans to permanently extend these emergency benefit changes past the public health emergency (PHE) period.66 The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 also included several provisions designed to expand Medicaid benefits, including expanded federal funding for home and community-based services (HCBS) and for COVID-19 treatment and vaccination.67

Prior to the pandemic, the use of telehealth in Medicaid was becoming more common.68 While all states had some form of Medicaid coverage for services delivered via telehealth, state policies regarding allowable services, providers, and originating sites varied widely.69 To increase health care access and limit risk of viral exposure during the pandemic, states used Medicaid emergency authorities to expand telehealth coverage and also took advantage of broad authority to further expand telehealth without the need for CMS approval.70 For example, states expanded the range of services that can be delivered via telehealth; established payment parity with face-to-face visits; expanded permitted telehealth modalities (e.g., audio-only telephone communication); and broadened the provider types that may be reimbursed for telehealth services. Preliminary CMS data shows that utilization of telehealth in Medicaid and CHIP has dramatically increased during the pandemic,71 but telehealth access is not equally available to all Medicaid enrollees. For example, while telehealth has the potential to facilitate greater access to care for Medicaid enrollees in rural areas with fewer provider and hospital resources,72 inadequate and/or unaffordable broadband access can be a barrier.73 Prior to the pandemic, one in four Medicaid enrollees lived in a home with limited internet access, with higher rates of limited access among non-White enrollees, older enrollees, and enrollees living in non-metro areas.74 The American Rescue Plan Act75 of 2021 included funding for rural health facilities to increase telehealth capabilities, and the Biden Administration has announced investments to strengthen telehealth in rural and underserved communities.76

This section provides information about:

- Non-emergency benefits and

- Telehealth

Findings

Non-Emergency benefits

We asked states about non-emergency benefit changes implemented during state fiscal year (FY) 2021 or planned for FY 2022, excluding temporary changes adopted via emergency authorities in response to the COVID-19 pandemic but including any emergency changes that have or will become permanent (i.e., transitioned to traditional, non-emergency authorities).77 Benefit changes may be planned at the direction of state legislatures and may require CMS approval.

The number of states reporting new benefits and benefit enhancements greatly outpaced the number of states reporting benefit cuts and limitations (Figure 3 and Table 2).78 Twenty-two states reported new or enhanced benefits in FY 2021, and 29 states are adding or enhancing benefits in FY 2022. Three states reported benefit cuts or limitations in FY 2021 and two states reported benefit cuts or limitations in FY 2022. We provide additional details about several benefit categories below (Exhibit 1). In addition to benefit categories discussed below, several states reported updated and expanded benefits in HCBS waivers. HCBS changes are a key area to watch in FY 2022 as states may expand covered services using the American Rescue Plan Act’s HCBS federal match rate (“FMAP”) increase; however, these spending plans may not have been finalized ahead of survey completion.79

Behavioral Health Services

States continue to focus on behavioral health through the introduction of new and expanded mental health and/or substance use disorder (SUD) benefits in FY 2021 and FY 2022. For example, states report implementing or plans to implement coverage of intensive outpatient services, clinic services, school-based services, and supportive employment services. State approaches to targeting SUD include new or expanded residential/inpatient SUD benefits and coverage of opioid treatment programs.80 Examples of targeted behavioral health services enhancements/additions include:

- If approved by CMS, Illinois will implement a team-based model of care providing trauma recovery services for adults and children due to chronic exposure to firearm violence in FY 2022. This model will include outreach services, case management, community support services, and group and individual therapy.81

- California plans to become the first Medicaid program to cover dyadic care, beginning in FY 2022.82 Dyadic care is a family- and caregiver-focused model of care that provides for early identification of developmental and behavioral health conditions and supports prevention, coordinated care, child social-emotional health and safety, developmentally appropriate parenting, and maternal mental health. During a medical visit, the caregiver and child will be screened for behavioral health conditions, interpersonal safety, tobacco and substance misuse, and social determinants of health.

- Wisconsin is testing a new approach to care for individuals with SUD and other health conditions. This model, called the Hub and Spoke Health Home Pilot, will provide Integrated Recovery Support Services through “hubs” or lead agencies that deliver SUD treatment and supports and “spokes” that are community partners providing additional supports and care management.83

Pregnancy and Postpartum Services

States are expanding and transforming care for pregnant and postpartum women to improve maternal health and birth outcomes. Six states will newly cover services provided by doulas.84 Doulas are trained professionals who provide holistic support to women before, during, and shortly after childbirth. A few states are investing in the implementation or expansion of home-visiting programs to teach prevention, parenting, and other skills aimed at keeping children healthy and promoting self-sufficiency. Several states have or will expand behavioral health services for pregnant and postpartum women. For example, in 2021, Louisiana initiated coverage for tobacco cessation services during pregnancy and perinatal depression screening; in 2022, two states (Maine and Maryland) will implement or expand their Maternal Opioid Misuse (MOM) Model, a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) initiative for pregnant and postpartum women with opioid use disorder. Two states (Maryland and Tennessee) have or will implement coverage of dental services for pregnant or postpartum women. In addition to benefit changes aimed at improving maternal health, many states are pursuing eligibility changes in this area, especially through the American Rescue Plan Act’s new option to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage to 12 months via a state plan amendment.85

Dental Services

States aim to improve oral health by expanding covered dental benefits and extending coverage to new populations. Seven states added, expanded, or restored dental coverage for the adult population86 and several states expanded dental services for pregnant or postpartum women (counted separately and discussed above). Arizona is requesting Section 1115 waiver authority to expand covered adult dental services, which are currently limited to an emergency dental benefit only, for the AI/AN population. In FY 2021, Georgia and New York started covering Silver Diamine Fluoride (SDF). SDF is a topical agent that can be used to halt the development of cavities in children and adults.87

Housing and Housing-related Supports

Five states reported new and expanded housing-related supports, as well as other services and programs tailored for individuals experiencing homelessness or at risk of being homeless. All five states plan to implement these services in FY 2022. Arizona is requesting Section 1115 waiver authority to enhance housing services and interventions for certain beneficiaries who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless, including by: strengthening outreach strategies, securing funding for housing, and expanding available wraparound housing services and supports.88 The state is requesting federal funding for room and board for short-term, transitional housing (up to 18 months) for individuals leaving homelessness or institutional settings. In early FY 2022, Connecticut established four new service categories targeted to adults experiencing homelessness and high inpatient admissions: care plan development and monitoring, pre-tenancy and transition assistance, housing and tenancy sustaining services, and transportation. When North Carolina implements a new pilot program in FY 2022, called “Healthy Opportunities Pilots,” it will provide coverage of non-medical services to address housing instability and other needs related to social determinants of health (SDOH).89 The District of Columbia and Maine also reported plans to cover certain housing-related supports for certain high-need groups.

Benefit restrictions in FY 2021 and FY 2022 were infrequent and narrowly targeted. Benefit restrictions reflect the elimination of a covered benefit, benefit caps, or the application of utilization controls such as prior authorization for existing benefits. In FY 2021, Wyoming eliminated its chiropractic services benefit and imposed prior authorization for children’s mental health services in excess of thirty visits per calendar year; Utah imposed more restrictive quantity limits for medically necessary urine drug testing; and Missouri eliminated coverage of counseling and person-centered strategies consultation from its four Developmental Disabilities waivers. In FY 2022, South Carolina updated its Vaccines for Children coverage policy following direction from CMS, which resulted in the elimination of Medicaid coverage for component-based vaccine counseling.90

Telehealth

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of telehealth in Medicaid was becoming more common. While all states had some form of Medicaid coverage for services delivered via telehealth, the scope of this coverage varied widely across states.91 To understand the impact of the pandemic on telehealth service delivery, we asked states about telehealth coverage and reimbursement policies as of July 2021, including for live audio-visual and audio-only delivery; telehealth efficacy and utilization trends during the pandemic; changes to telehealth policy planned for FY 2022; and challenges regarding telehealth from the member, provider, and state Medicaid agency perspectives.

Coverage and Reimbursement of Telehealth

Nearly all responding states reported covering a range of fee-for-service (FFS) services delivered via audio-visual telehealth, with slightly fewer states reporting audio-only coverage for each service (Figure 4).92 States were asked to indicate what telehealth modalities (audio-visual and/or audio-only) were covered for each specified service as of July 1, 2021, and whether the service is “always” or “sometimes” covered via each modality. All or nearly all responding states reported that they sometimes or always covered audio-visual delivery of the specified behavioral health, reproductive health, therapy, and well/sick child services, with fewer states reporting audio-visual coverage of HCBS and dental services. Across all service categories, states reported covering audio-only services less frequently than audio-visual services. However, majorities of responding states do report sometimes or always covering audio-only delivery of each specified service and, notably, access to audio-only mental health and SUD telehealth services is available in nearly all responding states. In states that reported covering a service via telehealth “sometimes,” coverage typically depends upon clinical appropriateness or the nature of the service or visit. Thirty-three states with managed care organizations (MCOs) (out of 36 responding)93 report requiring MCOs to cover the same services via telehealth as covered in FFS; one MCO state indicated requiring MCOs to cover the same services “in part.”

All responding states ensure payment parity between telehealth and in-person delivery of FFS services, and most states require MCOs to maintain these same payment parity policies. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Medicaid telehealth payment policies were unclear in many states;94 however, during the PHE, many states issued temporary or permanent guidance in this area.95 As of July 1, 2021, 45 states (out of 47 responding) reported that they maintain payment parity between telehealth and in-person visits for all services and telehealth modalities,96 while two states reported generally having parity with some variation for audio-only reimbursement.97 Twenty-seven MCO states (out of 36 responding)98 require MCOs to maintain the same telehealth payment parity policies that are applied in FFS.

Telehealth Efficacy and Utilization During COVID-19 Pandemic

An overwhelming majority of states noted the benefits of telehealth in maintaining or expanding access to care during the pandemic, particularly for behavioral health services. We asked states for examples of services delivered via telehealth and/or modalities that were particularly effective in improving access and/or health outcomes since the beginning of the pandemic. States commonly identified expanded audio-only coverage and allowing the enrollee’s home as an originating site as particularly effective policy flexibilities. Thirty-one states (out of 45 responding) reported that telehealth had particular value in maintaining or improving access to behavioral health services. We also asked states to list the top two or three categories of physical health and behavioral health services that had the highest telehealth utilization during FY 2021:

- For physical health services, states most frequently identified physician office visits and therapy services, particularly speech and hearing services.

- For behavioral health services, states most frequently identified psychotherapy, counseling (for mental health conditions and/or substance use disorder), and patient evaluations.

States reported telehealth utilization across all population groups during the pandemic, with considerable state-by-state variation in the eligibility groups with highest utilization. We asked states to identify trends in telehealth utilization by eligibility group and by other demographic categories:

- Telehealth utilization by eligibility group. A similar number of states identified that telehealth utilization was highest for adult eligibility categories (especially the Medicaid expansion group, but also parents and pregnant women) as states that identified that utilization was highest for children. Many states reported particularly high telehealth utilization among people with disabilities. Utilization trends may vary by service: for example, Utah noted that adult populations (including expansion adults, pregnant women, and parents) have had higher telehealth utilization for behavioral health services, whereas other populations (including children, elderly, and people with disabilities) have had higher utilization for physical health services.

- Telehealth utilization by race/ethnicity. A few states reported utilization trends by race/ethnicity, nearly all of which identified higher telehealth use for White, non-Hispanic adults. For example, California noted that the rate of telehealth visits among Hispanic beneficiaries was 10% lower than the statewide rate.

- Telehealth utilization by geography (urban vs. rural). We asked states whether rural or urban populations had experienced greater growth in telehealth utilization since the onset of the pandemic. Of the states that answered this question, 16 saw similar growth in rural and urban areas, ten observed higher growth in urban populations, and only two states observed higher growth in rural populations.99 Some states reported that audio-only coverage helped to expand access in rural areas that may not offer broadband coverage.

Post-Pandemic Policies and Telehealth Challenges

Post-pandemic telehealth coverage and reimbursement policies are under consideration in most states, with states weighing expanded access against quality concerns especially for audio-only telehealth. Across service categories, the majority of states reported that FY 2022 changes to telehealth coverage policies were “undetermined” at the time of the survey. Similarly, while eleven states indicated plans to change FFS telehealth reimbursement policies in FY 2022, 25 states have not yet determined whether changes will occur.100 In particular, plans for post-pandemic audio-only telehealth coverage and reimbursement parity vary by state. Many states identified that expanded audio-only coverage during the pandemic was particularly important for maintaining and expanding access to care, especially in rural areas and for older populations. However, states also expressed uncertainty regarding the legal authority to continue reimbursing audio-only telehealth services post-PHE due to state and federal privacy laws, as well as concerns about the clinical effectiveness and quality of audio-only visits for some services. States that did report plans to maintain audio-only coverage post-PHE particularly highlighted the continued use of this modality for mental health and SUD services.

Key factors under consideration for post-pandemic telehealth policy, including audio-only, include:

- Evaluation of telehealth access, utilization, and outcomes. Many states cited anecdotal feedback and preliminary data analysis suggesting that expanded telehealth has been viewed positively by members and providers and has decreased barriers to care. However, states also note that ongoing and planned review of data is necessary to further evaluate the impacts of telehealth expansions on access and health outcomes.

- Quality assurances and clinical appropriateness. States reported working to determine what services are clinically appropriate to be delivered via various telehealth modalities. While states may allow providers to make decisions of clinical appropriateness in some cases, states are working on developing guidelines and guardrails to ensure quality.

- Coordination with policies in other states, from other payers, and at the federal level. States are awaiting federal guidance relevant to allowable telehealth modalities. In many cases, states also note an interest in telehealth policies in other state Medicaid programs, Medicare, and private insurers.

- Costs of expanded telehealth. States reported budgetary questions and concerns about expanded telehealth, especially pertaining to whether increased telehealth use substitutes for in-person visits or contributes to overall increased utilization.

Commonly reported challenges associated with telehealth include access to internet and technology, as well as needs for education/outreach and quality assurances. Exhibit 2 highlights telehealth-related barriers reported by states from member, provider, and state Medicaid agency perspectives. Nearly all responding states reported that inadequate access to internet or technology was a barrier to telehealth utilization for members and/or providers. Other barriers for members include the need for outreach about the availability of telehealth and education on how to use telehealth technologies. Other barriers for providers include needs related to staffing, training, and help navigating a complex set of regulations and billing rules. At the agency level, states expressed concerns about assuring clinical effectiveness and quality, program integrity, and equity. Several states also identified challenges or concerns related to development of telehealth policy post-PHE and the need for federal guidance.

Social Determinants of Health

Context

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age that shape health. Prior to the pandemic, non-health and health sectors have engaged in initiatives to address SDOH. In response to the pandemic, federal legislation was enacted to provide significant new funding to address the pandemic’s health and economic effects including direct support to address food and housing insecurity, stimulus payments to individuals, federal unemployment insurance payments, and expanded child tax credit payments. While measures like these have a direct impact in helping to address SDOH, health programs like Medicaid can also play a supporting role. Although federal Medicaid rules prohibit expenditures for most non-medical services, state Medicaid programs have developed strategies to identify and address enrollee social needs both in managed care and fee-for-service (FFS) delivery systems.101 CMS released guidance for states about opportunities to use Medicaid and CHIP to address SDOH in January 2021.102

Communities of color have higher rates of underlying health conditions compared to White people and are more likely to be uninsured or report other health care access barriers.103 The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated already existing health disparities for a broad range of populations, but specifically for people of color.104 Multiple analyses of available federal, state, and local data show that people of color are experiencing a disproportionate burden of COVID-19 cases and deaths.105 In addition to worse health outcomes, data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey show that over the past year, Black and Hispanic adults have fared worse than White adults across nearly all measures of economic and food security.106

As the U.S. continues to grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic, the latest KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor finds that more than seven in ten U.S. adults (72%) now report being at least partially vaccinated, with the surge in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths due to the Delta variant being the main motivator for the recently vaccinated.107 The largest increases in vaccine uptake between July and September were among Hispanic adults and individuals ages 18-29, and similar shares of adults now report being vaccinated across racial and ethnic groups (71% of White adults, 70% of Black adults, and 73% of Hispanic adults). Large differences in self-reported vaccination rates remain between older and younger adults, individuals with and without college degrees, and those with higher and lower incomes. Adults living in rural areas continue to have lower vaccination rates than those living in urban and suburban areas. Because Medicaid covers over 82 million enrollees, including groups disproportionately at risk of contracting COVID-19, state Medicaid programs and Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) (which enroll over two-thirds of all Medicaid beneficiaries)108 can be important partners in COVID-19 vaccination efforts.109

This section provides information about:

- Initiatives to address social determinants of health;

- Efforts to expand community health worker workforce;

- Initiatives to address disparities in health care by race/ethnicity in Medicaid; and

- COVID-19 vaccine-related MCO initiatives

Findings

Initiatives to address Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health include but are not limited to housing, food, education, employment, healthy behaviors, transportation, and personal safety. Addressing social determinants of health is important for improving health and reducing longstanding disparities in health and health care. Although federal Medicaid rules prohibit expenditures for most non-medical services, state Medicaid programs have been developing strategies to identify and address enrollee social needs both within and outside of managed care.110

The vast majority of responding states that contract with MCOs (33 of 37) reported leveraging MCO contracts to promote strategies to address the social determinants of health in FY 2021 (Figure 5). In this year’s survey, MCO states were asked about MCO contract requirements related to social determinants of health in place in state fiscal year (FY) 2021 or planned for implementation in FY 2022. More than half of responding MCO states reported the following requirements were in place in FY 2021: screening enrollees for behavioral health needs, providing referrals to social services, partnering with community-based organizations (CBOs), and screening enrollees for social needs. About half of responding MCO states reported requiring or planning to require uniform SDOH questions within MCO screening tools. Fewer states reported requiring MCOs to track the outcomes of referrals to social services or requiring MCO community reinvestment (e.g., tied to plan profits or MLR) compared to other strategies; however, a number of states indicated plans to require these activities in FY 2022.

The following are examples of state MCO initiatives related to social determinants of health:

- Arizona’s Whole Person Care Initiative, which was launched in November 2019, seeks to address social risk factors in collaboration with MCOs, community-based organizations, tribal partners, providers, and other external stakeholders. The Whole Person Care Initiative: provides support for transitional housing for certain high-need enrollees (e.g., those experiencing chronic homelessness or transitioning from correctional facilities); leverages existing non-medical transportation services to support member access to community-based services; works to reduce social isolation among Medicaid enrollees using long-term care services; and is partnering with Arizona’s Health Information Exchange to establish a statewide closed-loop referral system.111

- In FY 2021, North Carolina launched a new pilot program, called “Healthy Opportunities Pilots,” to cover non-medical services to address housing instability, transportation insecurity, food insecurity, interpersonal violence, and toxic stress for a limited number of high-need enrollees in managed care plans.112 Healthy Opportunities “Network Leads” will develop, contract with, and manage the network of human service organizations that will deliver pilot services. MCOs in participating regions will be required to participate and will manage the pilot budget, enrollee eligibility, and authorize pilot services as well as work in collaboration with Network Leads to track pilot services.

- Tennessee plans to procure a closed loop referral system to support MCOs and providers in screening for social needs, making referrals to social services, and tracking follow-up. The system is scheduled to be implemented in 2022.

In addition to initiatives through MCOs, many states have strategies outside of their MCO programs (in FFS programs) to address social determinants of health.113 This year’s survey asked all states about non-MCO initiatives in place in FY 2021 or planned for implementation in FY 2022 related to social determinants of health. About half of responding states reported non-MCO initiatives in place in FY 2021 related to screening enrollees for social needs, screening enrollees for behavioral health needs, providing enrollees with referrals to social services, and partnering with CBOs or social service providers. About a quarter of states or fewer reported non-MCO initiatives in place in FY 2021 to employ community health workers, encourage/or require providers to capture SDOH data using ICD-10 Z codes, track the outcomes of referrals, or incorporate uniform SDOH questions within screening tools.

Medicaid Initiatives to Address SDOH in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Over half of responding states reported that the COVID-19 pandemic caused their state to implement, expand, or reform a Medicaid program that addresses enrollees’ social determinants of health. States reported a variety of initiatives; however, the most commonly reported initiatives were related to food/nutrition assistance and/or housing. Notable examples include:

- Arizona’s Medicaid agency established a partnership with a community provider that has access to the Homeless Management Information System (HMIS).114 HMIS is used to collect data on the provision of housing and services to homeless individuals and families and persons at risk of homelessness.115 The state Medicaid agency obtains weekly reports with Medicaid members found in HMIS who test positive for COVID-19 and have recently accessed homeless services. The state Medicaid agency shares this information with MCOs so that they can conduct outreach to these Medicaid enrollees and provide care management and follow-up services.

- California expanded its "Whole Person Care" (WPC) pilot program in response to the pandemic.116 The WPC program aims to coordinate care (physical, behavioral, and social services) for high-risk, high-utilizing Medicaid (Medi-Cal) enrollees and increase integration and data sharing among county agencies, health plans, and CBOs. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the pilot was expanded to allow participating counties to offer care coordination and other services to Medi-Cal enrollees who contracted COVID-19 or were at-risk of contracting COVID-19. For example, some WPC counties expanded housing services available (frequently for individuals experiencing homelessness) as well as other care management and wrap-around services. The state was able to leverage the WPC pilots and existing community partnerships to quickly mobilize in response to the pandemic to reach the most vulnerable Medi-Cal enrollees.117

- North Carolina leveraged the design of its “Healthy Opportunities Pilots" to create a similar program in select counties that funded CHWs to screen and refer individuals who needed to isolate or quarantine due to COVID-19 to medical and non-medical services, and then funded services including non-congregate shelter, home-delivered meals and groceries, COVID-19 relief payments, medication and COVID-19-related supplies, and transportation.118 To support this effort, the NC Department of Health and Human Services braided funds including COVID-19 relief funds, FEMA funds, and state Medicaid funds. Early results from this program showed participating in the program was associated in a 12-15% decrease in COVID-19 positivity rates in counties with the program relative to control counties. Health equity was a major focus of this initiative and over 70% of support services were provided to historically marginalized populations.

Efforts to expand community health worker Workforce

More than half of states reported Medicaid workforce initiatives in place in FY 2021 or planned for FY 2022 to expand the number of community health workers in the state. Community Health Workers (CHWs) can play an important role in addressing social determinants of health. CHWs are frontline workers who have close relationships with the communities they serve, allowing them to better liaise and connect community members to healthcare systems.119 CHW examples include care coordinators, community health educators, outreach and enrollment agents, patient navigators, and peer educators. CHWs can provide support to Medicaid enrollees by facilitating care coordination, providing culturally competent care, and linking enrollees to relevant resources and services.120 ,121 CHWs also have played an important role in trying to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.122 Historically, most CHW programs have been run and funded through community health centers and other community-based organizations. This year’s survey asked states to describe any Medicaid workforce initiatives underway in FY 2021 or planned for FY 2022 to expand the number of CHWs. States reported initiatives including:123

- Adding CHWs as a Medicaid covered service. Five states plan to add CHWs as a Medicaid covered service in FY 2022 (California, Illinois, Louisiana, Nevada, and Wisconsin).

- Adding CHWs as a Medicaid provider type. Four states reported they are establishing or planning to establish CHWs as a Medicaid provider type (Arizona, California, District of Columbia, and Illinois). For example, California is exploring adding CHWs as a provider type through a State Plan Amendment for preventative services in both the fee-for-service and managed care setting.

- Integrating CHWs into case or care management efforts. Two states are incorporating CHWs into case management redesign/care coordination improvement efforts (Colorado and Oregon). Additionally, Oregon passed state legislation that will officially recognize Tribal Traditional Health Workers as a type of CHW.124 CHWs are required to be included as an available service in managed care contracts in Oregon, meaning that Tribal CHWs will become more available for those who need them.125

State Medicaid CHW Workforce Initiative Examples

- California, starting on January 1, 2022, will allow their MCOs to begin offering certain “in lieu of” services which they expect will increase the number of CHWs MCOs contract with. California is also exploring the ability to allow community-based organizations to participate in its Medicaid program as an enrolled provider of CHWs.

- As part of Illinois’ first round of grant funding for its “Healthcare Transformation Collaboratives” program,126 the state will support the work of CHWs and will apply lessons learned within the Medicaid program. The Healthcare Transformation Collaborative, created in January 2021, seeks to fund collaboratives between healthcare providers and community-based organizations to increase access to preventative care, chronic disease management, and obstetrics care, and ultimately improve health outcomes.127

- Missouri’s Medicaid agency has a contract with the Missouri Primary Care Association to expand the Community Health Worker Program designed to address social determinants of health, improve patient engagement in preventative care, provide chronic disease management and self-management services, connect patients with community-based services, and reduce potentially avoidable emergency room visits and hospital admissions and readmissions.

initiatives to address disparities in health care by race/ethnicity in Medicaid

Communities of color have higher rates of underlying health conditions compared to White people and are more likely to be uninsured or report other health care access barriers.128 The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated already existing health disparities for a broad range of populations, but specifically for people of color.129

Three-quarters of responding states reported initiatives in place in FY 2021 or planned for FY 2022 to address disparities in health care by race/ethnicity in Medicaid. We asked states to identify innovative or notable initiatives in this area, and many of the state responses overlapped with initiatives also reported elsewhere on the survey. About half of responding states reported managed care requirements and/or initiatives to address health disparities, including Performance Improvement Projects (PIPs), requirements that MCOs achieve the NCQA Distinction in Multicultural Health Care,130 and pay-for-performance (P4P) initiatives. Nearly half of responding states reported focusing on using data to address health disparities, including by stratifying quality and other measures by race/ethnicity. Many of these states planned to expand or improve data collection to better identify disparities. A few states reported that eligibility or benefit expansions would address health disparities, particularly for pregnant and postpartum women, non-citizens, and justice-involved populations. Many states cited efforts to diversify, support, and/or train workforces to increase cultural competency, including by partnering with community-based organizations.

Twenty states reported initiatives to address disparities in specific health outcomes, including maternal and infant health, behavioral health, and COVID-19 outcomes and vaccination rates (Exhibit 3). For example:

- To address disparate maternal health outcomes for Black women, Connecticut is developing a comprehensive maternity bundled payment that includes obstetrician/nurse midwife services, doulas, community health workers, and breastfeeding support. Pennsylvania reported a P4P maternity care bundled payment arrangement that will reward providers that reduce racial disparities.131

- Since FY 2020, Michigan has used capitation withholds to incentivize reductions in racial disparities in behavioral health metrics. California’s value-based payment program directs MCOs to address health disparities by making enhanced payments that target serious mental illness, substance use disorder, and homelessness.

- Several states reported efforts to reduce disparities in COVID-19 vaccination rates. For example, one of Iowa’s MCOs has developed a vaccine outreach program that monitors for low uptake among traditionally underserved member groups (including by race and language).

- Two states cited programs to reduce disparities in diabetes outcomes. Maine is supporting the training of community health workers to provide culturally engaging outreach around diabetes management. In FY 2021, Ohio focused on reducing diabetes disparities through an MCO PIP.

COVID-19 Vaccine-Related MCO Initiatives

Currently, there are three COVID-19 vaccines approved for use in the U.S. States and public health agencies are playing a central role in vaccine distribution and the public health promotion of these vaccines. Because Medicaid covers over 82 million enrollees, including groups disproportionately at risk of contracting COVID-19, state Medicaid programs and Medicaid MCOs can be important partners in COVID-19 vaccination efforts.132

States report a variety of MCO activities aimed at promoting the take-up of COVID-19 vaccinations. Given that MCOs provide services to over two-thirds of Medicaid enrollees, states were asked to describe any known programs, initiatives, or value-added services newly offered by MCOs to promote take-up of COVID-19 vaccinations.133 States reported a wide variety of initiatives including: member and provider incentives, member outreach and education (including targeted outreach to high-risk members or areas demonstrating disparities in access or take-up), provider engagement, assistance with vaccination scheduling and transportation coordination, and partnerships with state and local organizations, especially related to community-specific events, like vaccination clinics/events. Examples include:

- In Indiana, the state is tracking COVID-19 vaccinations by plan, geographic location, and demographics including race and ethnicity to help guide targeted MCO outreach.

- In Iowa, Amerigroup has been strategically redirecting traditional community relations giveaway items as part of community vaccination clinic efforts. For example, Amerigroup distributed 300 coffee shop gift cards (in the amount of $5) to college students in Iowa City to promote participation in a vaccination clinic.

- In Michigan, MCOs are employing a variety of strategies to increase COVID-19 vaccinations including member and provider incentives, using CHW workforce to provide education and outreach to address vaccine hesitancy, and partnering with community-based organizations to provide vaccines where people can easily access them.

- In Pennsylvania, MCOs have performed analysis to identify members who were at high risk for complications from COVID-19 and conducted outreach to those members to encourage vaccination. The managed care long-term services and supports (MLTSS) MCOs also coordinated to establish vaccination clinics specifically dedicated to serving their membership through partnerships with large pharmacies.

- In Utah, the state shares information with Medicaid MCOs regarding the immunization status of enrollees on a monthly basis. MCOs conduct member outreach, coordinate with PCPs, and offer incentives to enrollees (e.g., gift cards).

- In Washington, MCOs are tracking COVD-19 vaccine data within their enrollment and performing targeted outreach to members.

Although not specifically asked, several states also discussed incentives in place for MCOs to increase COVID-19 vaccination rates. For example:

- In Florida, the state Medicaid agency incentivized managed care plans to work to increase vaccination uptake. For plans that achieved a greater than 50% first dose vaccination rate for members 50 years or older by August 31, 2021, the plan accrued a dollar amount per enrollee that can be used to offset any liquidated damages assessed for calendar year (CY) 2020.134

- Hawaii added an MCO P4P process measure for CY 2021 to focus MCOs on increasing COVID-19 vaccine uptake within the Medicaid population.

- Louisiana Medicaid implemented COVID-19 vaccination administration MCO incentive payments to encourage MCOs to increase vaccination rates. The state is leveraging a pre-existing managed care incentive payment program which allows for incentive payments above the capitation rate if performance targets are met. The state indicates MCOs that achieve targets and receive incentive payments could then use these funds to create member and/or provider vaccination incentives. The state is leveraging MCO performance improvement project (PIP) reporting structures that are already in place to monitor MCO performance on vaccine administration.

Provider Rates and Taxes

Context

Fee-for-service (FFS) provider rate changes generally reflect broader economic conditions. During economic downturns where states may face revenue shortfalls, states have typically turned to provider rate restrictions to contain costs. Conversely, states are more likely to increase provider rates during periods of recovery and revenue growth. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, has changed this historic dynamic. With many providers facing financial strain from the increased costs of COVID-19 testing and treatment or from declining utilization for non-urgent care, especially in the early months of the pandemic, states facing budget challenges likely found rate reductions to be less feasible.135 At the same time, starting early in the pandemic, Congress, states,136 and the Administration adopted a number of policies to ease financial pressure on hospitals and other health care providers.137 Also, while most states increasingly rely on capitated arrangements with managed care organizations (MCOs) to deliver Medicaid services to most of their Medicaid populations, state-determined FFS rates remain important benchmarks for MCO payments in many states, often serving as the state-mandated payment floor.

In state fiscal year (FY) 2019, state payments to MCOs comprised about 46% of total Medicaid spending.138 State capitation payments to MCOs and limited benefit prepaid health plans (PHPs) must be actuarially sound,139 but within this broader constraint, states use a variety of mechanisms to adjust managed care plan risk, incentivize performance, and ensure plan payments are not too high or too low.140 To further state goals and priorities, including COVID-19 response, states can also implement CMS-approved “directed payments” that require MCOs and/or PHPs to apply certain methodologies (e.g., minimum fee schedules or uniform increases) when making payments to specified provider types. For example, CMS has permitted states to implement directed payments to ensure funds continue to flow to providers during the pandemic, even if utilization had decreased, but also permitted states to make pandemic-related adjustments to managed care contracts and capitation rates to provide financial protection and limits on financial risk for states and plans.

States have considerable flexibility in determining how to finance the non-federal share of state Medicaid payments, within certain limits. In addition to state general funds appropriated directly to the state Medicaid program, most states also rely on funding from health care providers and local governments generated through provider taxes, intergovernmental transfers (IGTs), and certified public expenditures (CPEs).141 Over time, states have increased their reliance on provider taxes, with expansions often driven by economic downturns.142

This section provides information about:

- FFS reimbursement rates;

- MCO capitation rate setting;

- Managed care plan (MCO & PHP) payment requirements; and

- Provider taxes

Findings

FFS reimbursement Rates

At the time of the survey, responding states had implemented or were planning more FFS rate increases than rate restrictions in both FY 2021 and FY 2022 (Figure 6 and Tables 3 and 4). In FY 2021, 42 states (out of 47 responding) reported implementing rate increases for at least one category of provider and 27 states reported implementing rate restrictions. In FY 2022, slightly more states reported at least one planned rate increase (45 states) and the number of states planning to restrict rates decreased slightly (26 states).

States reported rate increases for nursing facilities and home and community-based services (HCBS) providers more often than other provider categories (Figure 7). As discussed further below, approximately two-thirds of the states reporting a nursing facility or HCBS rate increase indicated that the increase was related, at least in part, to the COVID-19 pandemic. While states reported imposing more restrictions on inpatient hospital and nursing facility rates than on other provider types, most of these restrictions were rate freezes rather than actual reductions. (Because inpatient hospital and nursing facility services are more likely to receive routine cost-of-living adjustments than other provider types, this report counts rate freezes for these providers as restrictions.) Two states (Colorado and Wyoming) reported rate reductions across most provider categories in FY 2021; three states (California, Idaho, and North Carolina) reported rate reductions across most provider categories in FY 2022; and Mississippi reported that its legislature had enacted a rate freeze for all providers for FY 2022 through FY 2024. Broader rate cuts across provider types are often linked to budget shortfalls.

More than two-thirds of responding states (33 of 47) indicated that one or more payment changes made in FY 2021 or FY 2022 are related in whole or in part to COVID-19. Across provider types, the vast majority of COVID-19-related payment changes were rate increases. COVID-19-related payment changes were most commonly associated with nursing facilities (27 states) and HCBS providers (26 states). Additionally, states reported a variety of other FFS payment changes in FY 2021 or planned for FY 2022 in response to COVID-19 including: increasing COVID-19 vaccine reimbursement rates to 100% of the Medicare rate (approximately $40 per dose) and allowing a broader range of providers to be reimbursed for vaccine administration such as pharmacists, home health agencies, ambulance providers, renal dialysis clinics, and outpatient behavioral health clinics; making retainer payments to HCBS providers and bed hold payments to institutional providers; and making supplemental or add-on payments to certain providers, especially nursing facilities, for COVID-19 patients.143

MCO capitation rate setting

This year’s survey asked states about remittances related to minimum medical loss ratios as well as the use of risk corridors in MCO contracts.

Minimum Medical Loss Ratios

The Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) reflects the proportion of total capitation payments received by an MCO spent on clinical services and quality improvement (where the remainder goes to administrative costs and profits). CMS published a final rule in 2016 that requires states to develop capitation rates for Medicaid managed care plans to achieve an MLR of at least 85% in the rate year, for rating periods and contracts starting on or after July 1, 2019.144 Analysis of National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) data for the Medicaid managed care market show that annual loss ratios in 2020 (in aggregate across plans) decreased by four percentage points from 2019 (and three percentage points from 2018), but still met the 85% minimum even without accounting for potential adjustments.145

Contracts taking effect on or after July 1, 2017 must include a requirement for plans to calculate and report an MLR.146 The 85% minimum MLR is the same standard that applies to Medicare Advantage and private large group plans. There is no federal requirement for Medicaid plans to pay remittances to the state if they fail to meet the MLR standard, but states have discretion to require remittances. (A state and the federal government share in any remittances in proportion to the state’s federal matching rate—if the state requires remittances). For a limited time (from federal fiscal years 2021 through 2023), The Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities (SUPPORT) Act permits states to keep their regular state share of any remittances paid by Medicaid plans for expansion adults rather than only 10%.147

More than half of states that contract with MCOs always require MCOs to pay remittances when minimum MLR requirements are not met. States were asked whether they require MCOs that do not meet minimum MLR requirements to pay remittances. Of the 37 MCO states that responded to this year’s survey, 21 reported that they always require MCOs to pay remittances, while nine indicated they sometimes require MCOs to pay remittances (Exhibit 4). States reporting that they sometimes require remittances often limit this requirement to certain MCO contracts. For example, in Pennsylvania, physical health MCOs not meeting minimum MLR requirements are always required to pay remittances, while remittances for managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS) MCOs are at the Medicaid agency’s discretion. Likewise, Utah’s remittance requirements are limited to MCO contracts for the adult expansion population. In the District of Columbia, an MCO with an MLR less than 85% may be required to remit payments or be subject to other corrective actions. One state (South Carolina) reported allowing an exception to the remittance requirement if an MCO achieved a high National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) health insurance plan rating. Seven states reported that they do not require remittances when their plans do not meet the minimum MLR requirement.

COVID-19 Risk Corridors

The COVID-19 pandemic caused major shifts in utilization across the healthcare industry that could not have been anticipated and incorporated into MCO capitation rate development for 2020 and 2021. CMS therefore allowed states to modify managed care contracts and rates in response to the pandemic, including through the imposition of risk corridor arrangements, where states and health plans agree to share profit or losses (at percentages specified in plan contracts) if aggregate spending falls above or below specified thresholds (two-sided risk corridor).148

More than half of MCO states implemented COVID-19-related risk corridors in their 2020 or 2021 contracts; about half of these states reported that they have or will recoup funds, while recoupment in the remaining states remains undetermined (i.e., yet to be reconciled) (Exhibit 5). Twenty-one of 37 responding MCO states reported imposing risk corridors in their MCO contracts for all or part of FY 2020 or FY 2021 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. State MCO contract periods may be on a calendar year, fiscal year, or another period.149 One state (Hawaii) had risk corridors already in place but narrowed them in response to the pandemic. Of these 21 states, nine reported that recoupments had already occurred or were expected while 12 reported that potential recoupments remained undetermined. Tennessee noted that potential recoupments were undetermined but that any potential recoupments would be mitigated by utilization-based capitation rate reductions imposed in 2020. A number of states noted having risk corridors in place for at least one MCO program unrelated to the pandemic.150

Managed care PLAN (mco & php) payment requirements