Potential Effects of Public Charge Changes on Health Coverage for Citizen Children

| Key Findings |

| The Trump Administration is pursuing changes that, for the first time, would allow the federal government to take into account use of Medicaid, CHIP, subsidies for Marketplace coverage and other health, nutrition, and non-cash programs when making public charge determinations. These changes would likely lead to decreased participation in Medicaid, CHIP, Marketplace coverage, and other programs among legal immigrants and their citizen children, even though they would remain eligible. This brief provides an overview of citizen children with a noncitizen parent potentially affected by the changes and analyzes three Medicaid/CHIP disenrollment scenarios to illustrate how the changes could potentially affect their health coverage and uninsured rate.

In 2016, there were 10.4 million citizen children with at least one noncitizen parent. Nearly nine in ten of these children live in a family with a full-time worker, but these workers often are in low-wage jobs, leading to lower family incomes and more limited access to health coverage. As such, over half (56%), or 5.8 million, citizen children with a noncitizen parent had Medicaid or CHIP coverage in 2016. (See Appendix tables for state data.) We illustrate the potential impact of different Medicaid/CHIP disenrollment rates and show that, if the policy leads to disenrollment rates from 15% to 35%, an estimated 875,000 to 2 million citizen children with a noncitizen parent could drop Medicaid/CHIP coverage despite remaining eligible. The majority disenrolling would become uninsured, increasing their uninsured rate from 8% to between 14% and 22% and the uninsured rate for all children from 5% to between 6% and 7%. Although it is difficult to predict the effect of the policy change, these disenrollment rates illustrate the potential impact and draw on previous research on the chilling effect welfare reform had on enrollment of immigrant families. However, unlike the current draft policy, welfare reform did not affect immigration status. Thus, this illustrative analysis may underestimate the policy’s impact on Medicaid/CHIP participation. In addition, this analysis does not account for coverage losses that would result from decreased participation in Marketplace coverage. Coverage losses would negatively affect the health of children and their families’ financial stability. Coverage losses would reduce access to care, contributing to worse health outcomes. Moreover, reduced participation in nutrition and other support programs that are also proposed to be considered as part of public charge determinations would likely compound these effects. |

Introduction

The Trump Administration is pursuing changes that, for the first time, would allow the federal government to take into account use of health, nutrition, and other non-cash programs when making public charge determinations. Under these changes, use of these programs, including Medicaid, CHIP, and subsidies for Marketplace coverage, by an individual or family member, including a citizen child, could result in the federal government denying an individual a “green card” or adjustment to lawful permanent status or entry into the U.S. These changes would likely result in reduced participation in Medicaid, CHIP, Marketplace coverage, and other programs by immigrant families, including citizen children, even though they would remain eligible. Decreases in Medicaid and CHIP enrollment would increase the number of uninsured and reduce access to care, increase financial strains on families, and widen disparities in coverage. This brief provides an overview of citizen children with a noncitizen parent who could potentially be affected by the proposed changes and presents three Medicaid/CHIP disenrollment scenarios to illustrate how the changes could potentially affect their health coverage and uninsured rate. It is based on Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of Current Population Survey Data. (See Methods for more details.) Appendix Tables 2 and 3 provide state-specific data.

Overview of Citizen Children with a Noncitizen Parent

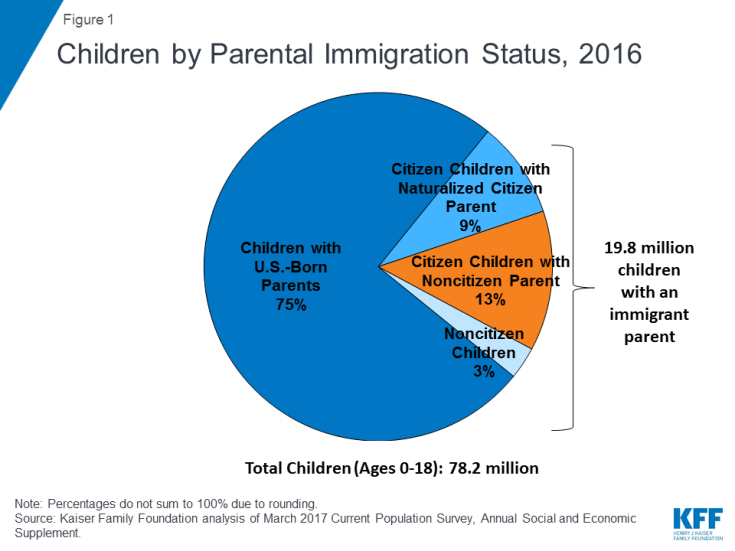

In 2016, nearly 20 million, or one in four, children had at least one immigrant parent, and nearly nine in ten (88%) of these children were citizens (Figure 1). Over half, or 10.4 million, of these children lived in mixed status families, where the child is a citizen and at least one parent is a noncitizen. Citizen children with a noncitizen parent are heavily concentrated in a few states. Over half of children with a noncitizen parent live in California (25%), Texas (16%), New York (7%), and Florida (6%) (Appendix Table 2).

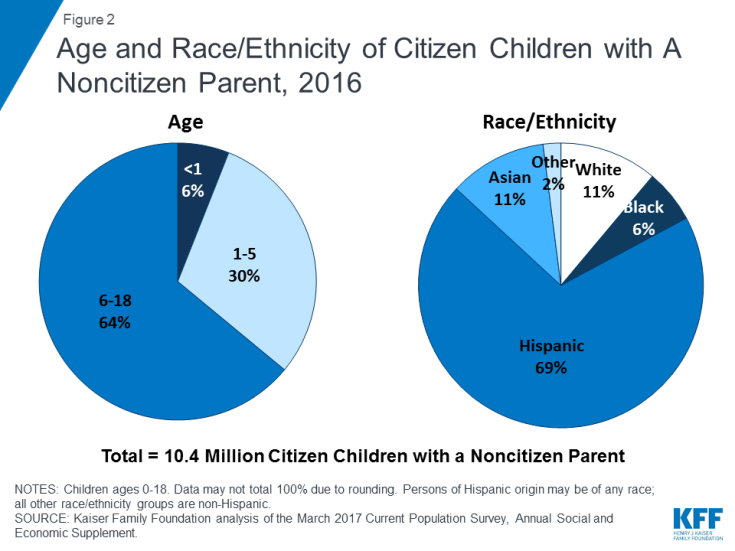

Citizen children with a noncitizen parent range in age and race/ethnicity, although the majority are between ages 6-18 and Hispanic (Figure 2). About one in three (36%) citizen children with a noncitizen parent are below age six; the remaining 64% are between ages 6-18. Over two-thirds (69%) of citizen children with a noncitizen parent are Hispanic and 11% are Asian. The remaining 19% includes 11% who are White non-Hispanic, 6% who are Black non-Hispanic, and 2% who are another or mixed race.

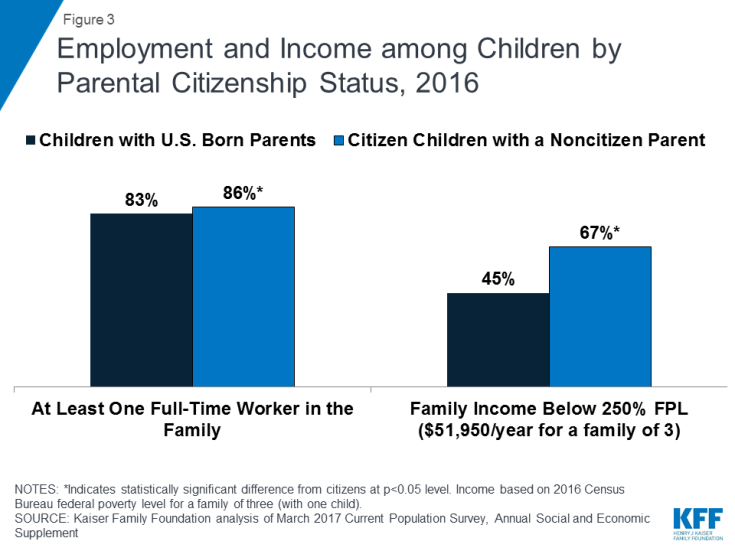

Although citizen children with a noncitizen parent are more likely to live in a family with a full-time worker compared to those with U.S. born parents, they have lower family incomes. Nearly nine in ten (86%) citizen children with a noncitizen parent live in a family with at least one full-time worker (Figure 3). However, over two-thirds (67%) of citizen children with a noncitizen parent have family incomes below 250% of the federal poverty level (FPL), compared to 45% of children with U.S. born parents. This finding reflects that noncitizens are often employed in low-wage jobs and industries.

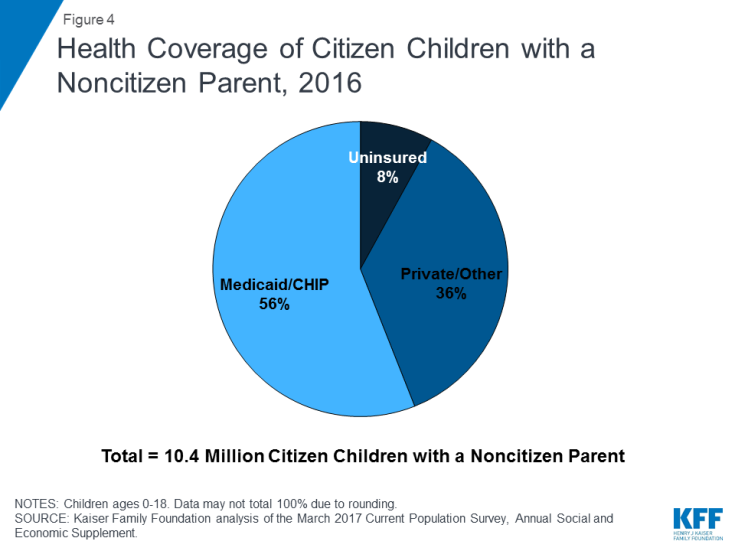

Reflecting their lower family incomes, Medicaid and CHIP play a key role in covering citizen children with a noncitizen parent, but they remain more likely than those with U.S. born parents to be uninsured. Given that over two-thirds of citizen children with a noncitizen parent have family incomes below 250% FPL, many are within the income eligibility limits for Medicaid or CHIP.1 As such, Medicaid and CHIP cover over half (56%), or 5.8 million, citizen children with a noncitizen parent. This coverage helps to fill gaps in private coverage since many noncitizen parents work in low-wage jobs that often do not offer health coverage. However, citizen children with a noncitizen parent remain more likely than children with U.S. born parents to be uninsured (8% vs. 5%). Moreover, their parents are more than three times as likely to be uninsured themselves compared to U.S. born parents (24% vs. 7%).

Potential Coverage Losses Due to Public Charge Policies

Under draft changes proposed by the Trump Administration, use of health, nutrition, and other non-cash programs by an individual or a family member, including a citizen child, could result in the federal government denying an individual adjustment to lawful permanent resident status (i.e., a “green card”) or entry into the United States.2 Under longstanding policy, individuals who are determined to be a “public charge” can be denied lawful permanent residence or entry into the U.S. Today, individuals may be determined a public charge if they rely on or are likely to rely on public cash assistance or government funded long-term institutional care. Current policy does not allow the federal government to consider the use of non-cash benefits, such as health and nutrition programs, in public charge determinations. Under the draft proposed changes, the federal government could consider previously excluded health, nutrition, and other non-cash programs in public charge determinations. These programs would include Medicaid, CHIP, and subsidies for Marketplace coverage. In addition, the changes would newly allow the federal government to take into account use of programs by citizen children and other family members in making a public charge determination.

The changes in public charge policy would likely lead to decreased participation in Medicaid, CHIP, Marketplace coverage, and other programs among legal immigrant families, including their citizen children, even though they would remain eligible. Fears of negative consequences on immigration status are a barrier to Medicaid and CHIP enrollment for eligible immigrant families today even though the federal government cannot consider use of Medicaid and CHIP in public charge determinations under current policy.3 The proposed changes would amplify these fears because use of Medicaid, CHIP, as well as subsidies for Marketplace coverage and other programs could negatively affect immigration status. The preamble to the draft proposed rule notes, “the action provides a strong disincentive for the receipt or use of public benefits by aliens, as well as their household members, including U.S. children.” It is expected that the public charge policy change would primarily affect individuals seeking a green card through a family-based petition. However, increased fears would likely extend beyond individuals directly affected by the policy to the broader immigrant community.4 Due to increased fears, it is likely that fewer eligible individuals would enroll themselves and their children in health coverage and individuals currently enrolled in programs would disenroll themselves and their children despite remaining eligible for coverage.

To illustrate potential effects of these changes on health coverage of children, we present three scenarios of disenrollment from Medicaid and CHIP among citizen children with a noncitizen parent. As of 2016, 5.8 million citizen children with a noncitizen parent were enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP (see Appendix 2 for state data), and 790,000 or 8% were uninsured. We applied disenrollment rates from Medicaid and CHIP of 15%, 25%, and 35%. Although it is difficult to predict the effect of the policy change, these disenrollment rates illustrate the potential impact and draw on previous research on the chilling effect welfare reform had on enrollment of immigrant families.5 However, unlike the current draft policy, welfare reform did not affect immigration status. Thus, this illustrative analysis may underestimate the impact that the policy may have on participation in Medicaid/CHIP. We assume that 75% of children disenrolling from Medicaid and CHIP would become uninsured based on data showing some access to private coverage among this population.6 However, some families may not be able to afford private coverage even if it is available. As such, this analysis may underestimate the share of children disenrolling from Medicaid/CHIP who would become uninsured. In addition, this analysis does not account for decreased coverage due to fewer individuals enrolling their eligible children in Medicaid or CHIP or coverage losses that would result from decreased participation in Marketplace coverage.

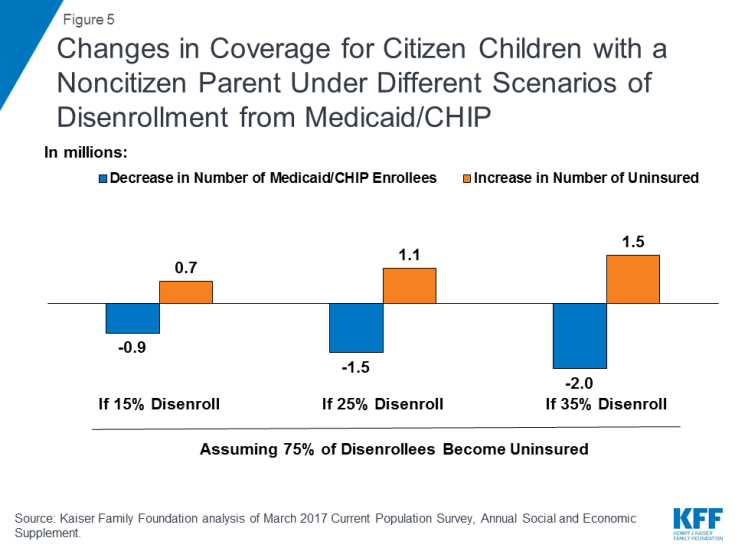

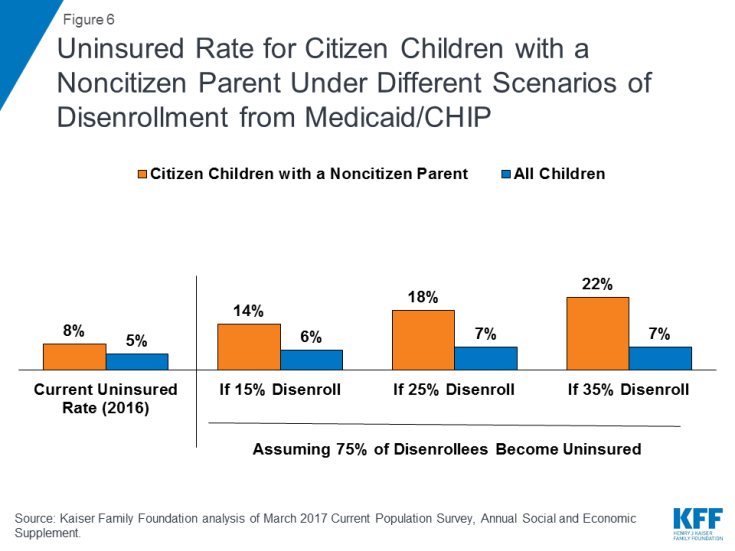

If the public charge policy change leads to Medicaid/CHIP disenrollment rates ranging from 15% to 35%, an estimated 875,000 to 2 million citizen children with a noncitizen parent could drop Medicaid/CHIP coverage despite remaining eligible, and their uninsured rate would rise from 8% to between 14% and 22%. Specifically, as shown in Figures 5 and 6 and Appendix Table 1:

- A 15% decline in Medicaid/CHIP enrollment among citizen children with a noncitizen parent would result in 875,000 children losing Medicaid/CHIP coverage and 657,000 becoming uninsured. These losses would increase the uninsured rate for citizen children with a noncitizen parent from 8% to 14%, and the uninsured rate for all children would increase from 5% to 6%.

- A 25% decline in Medicaid/CHIP enrollment among citizen children with a noncitizen parent would result in 1.5 million children losing Medicaid/CHIP coverage and 1.1 million becoming uninsured. These losses would increase the uninsured rate for citizen children with a noncitizen parent from 8% to 18%, and the uninsured rate for all children would increase from 5% to 7%.

- A 35% decline in Medicaid/CHIP enrollment among citizen children with a noncitizen parent would result in 2.0 million children losing Medicaid/CHIP coverage and 1.5 million becoming uninsured. These losses would increase the uninsured rate for citizen children with a noncitizen parent from 8% to 22%, and the uninsured rate for all children would increase from 5% to 7%.

Figure 5: Changes in Coverage for Citizen Children with a Noncitizen Parent Under Different Scenarios of Disenrollment from Medicaid/CHIP

Figure 6: Uninsured Rate for Citizen Children with a Noncitizen Parent Under Different Scenarios of Disenrollment from Medicaid/CHIP

Coverage losses would negatively affect the health of children and their families’ financial stability. Coverage losses would reduce access to care, contributing to worse health outcomes.7 Reduced participation in nutrition and other programs that are also proposed to be considered in public charge determinations would likely compound these effects. In particular, the Earned Income Tax Credit, free or reduced price lunch program, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and Women Infant and Children’s Program (WIC) provide important sources of support for these households (Appendix 3). Decreased participation in these programs would negatively affect the financial stability of families and the growth and healthy development of their children.8

| Methods |

| Findings in this brief are based on Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the March 2017 Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement. Children include individuals ages 0-18. For the analysis, children are grouped into mutually exclusive categories, including: children with U.S. born parents, citizen children in a household where at least one parent is a naturalized citizen, citizen children in a household where at least one parent is a noncitizen, and noncitizen children.

For estimates of potential changes in coverage due to public charge policies, we present several scenarios using different disenrollment rates for Medicaid and CHIP. These disenrollment scenarios are illustrative of the potential impact of the public charge policy change and draw on previous research on the chilling effect welfare reform had on enrollment of immigrant families. Specifically, Kaushal and Kaestner found 25% disenrollment among children of foreign-born parents.1 This study was most relevant to our analysis given its focus on children and its inclusion of children who remained eligible after the welfare reform changes. Using this 25% disenrollment rate as a midpoint, we also examined the impact if the disenrollment rate was lower at 15% or higher at 35% to illustrate the impact of alternate disenrollment rates given uncertainty about the actual impact if the policy is implemented. Because, unlike the current draft proposed policy, welfare reform did not affect immigration status, this illustrative analysis may underestimate the impact the policy may have on participation in Medicaid/CHIP. The estimates also assume that 75% of those disenrolling from Medicaid and CHIP would become uninsured. This assumption is based on Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of Current Population Survey data showing some access to private coverage among this population. However, this analysis may underestimate the share of children disenrolling from Medicaid/CHIP who would become uninsured since some families may not be able to afford private coverage even if it is available. Further, this analysis does not account for decreased coverage due to fewer individuals enrolling their eligible children in Medicaid or CHIP or coverage losses that would result from decreased participation in Marketplace coverage. 1 Neeraj Kaushal and Robert Kaestner, “Welfare Reform and Health Insurance of Immigrants,” Health Services Research,40(3), (June 2005), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1361164/ |

This brief was prepared by Samantha Artiga and Rachel Garfield, with the Kaiser Family Foundation, and Anthony Damico, an independent consultant to the Kaiser Family Foundation.