Early Insights from One Care: Massachusetts’ Demonstration to Integrate Care and Align Financing for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries

Introduction

In April 2011, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) awarded design contracts to Massachusetts and fourteen other states to develop a service delivery and payment model to integrate care for beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.1 States that were interested in pursuing more integrated dual eligible programs submitted proposals to CMS to launch demonstrations. To date, 11 states have signed agreements with CMS to initiate demonstrations to better align the financing of health care for seniors and/or younger people with disabilities who are dual eligibles and fall under CMS’s Section 1115A waiver authority to test models seeking to improve care coordination and quality and to reduce costs. Box 1 provides brief background about the demonstrations.2

| Box 1: State Integrated Care and Financial Alignment Demonstrations for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries |

| State Integrated Care and Financial Alignment Demonstrations for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries are the product of the joint efforts of states and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop more integrated ways to pay for and deliver health care to the more than 10 million seniors and younger people with disabilities who are eligible for both the Medicare and Medicaid programs. These individuals are among the poorest and sickest beneficiaries covered by either program. The demonstrations are an outgrowth of the Affordable Care Act and seek to test two new models (capitated and managed FFS) to align Medicare and Medicaid benefits and financing for dual eligible beneficiaries with the goal of delivering better coordinated care and reducing costs. |

Massachusetts was the first state to finalize a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU)3 with CMS to test a capitated financial alignment model in August 2012, and the first state to launch a 3-year capitated demonstration program – One Care – in October 2013. January and then April 2013 had been the original target dates for launching the Massachusetts demonstration, and these dates were pushed back to July and then October 2013. The launch date delays were indicative of the planning challenges associated with implementing significant financial and delivery system changes for beneficiaries with complex health needs. Delays also allowed additional time for parties to discuss and consider ideas and concerns arising from the extensive stakeholder engagement process throughout the demonstration design period. The demonstration is slated to be in operation through December 2016.

While the original plan was for One Care to be available statewide, it was implemented in October 2013 in nine of fourteen Massachusetts counties covering approximately 96,449 of the state’s estimated 110,000 dual eligible beneficiaries ages 21-64. Unique characteristics of the Massachusetts demonstration – relative to demonstrations in other states – are its focus on the non-elderly dual eligible population and its requirement that participating health plans contract with Independent Living Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) coordinators from community organizations to work with participating beneficiaries. This report describes the early implementation of the One Care demonstration for dual eligible beneficiaries in Massachusetts.4 These findings can inform the implementation of other states’ demonstrations in the coming months, as the first reports from CMS’s formal evaluation are not expected to be released until 2016.

Approach

To develop this report, we conducted semi-structured interviews with a diverse group of leaders involved in the design and early implementation of One Care. Interviews were conducted over a 9-month period from February through November 2014. We began conducting interviews in the fifth month following the program launch to give interviewees a few months to gain experience with One Care. We developed a semi-structured interview guide that included both general questions for all participants and targeted questions based on the unique perspectives of selected categories of interviewees. A total of 37 stakeholders were interviewed to capture the diverse perspectives of leaders in Massachusetts involved in the demonstration including individuals in multiple state government agencies involved in providing health and social services for the dual eligible population; medical, behavioral health, and social service provider organizations; consumer advocacy organizations; and health plans. All interviews were conducted by a team of two to four of the report’s authors, which allowed us an opportunity to compare observations and enhanced reliability in chronicling the early implementation of the One Care program. In a number of cases, we interviewed participants on multiple occasions over the 9-month study period to assess whether and how impressions of early implementation of One Care were evolving. We analyzed data collected during interviews using an iterative process to identify reoccurring themes. We also reviewed all public documents related to the planning and implementation of One Care.

Planning and Initiation of the One Care Demonstration

Massachusetts’ early interest in moving forward with the duals demonstration is consistent with its history of innovation in health reform. Nevertheless, certain factors were instrumental in spurring the development of an integrated model for under-65 dual eligible beneficiaries in the state. The state had moved most of its MassHealth (the state Medicaid program) under-65 beneficiaries into managed care unless they met certain exclusions such as having other health insurance, including Medicare. In contrast, dual eligible beneficiaries in the state were still receiving services predominately under an uncoordinated, fee-for-service (FFS) system. Massachusetts had substantial experience with care coordination under a small managed care program for seniors in the state (i.e., Senior Care Options (SCO)),5 and there was substantial interest in extending the care model to the state’s younger beneficiaries with disabilities. In addition, former Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick – a strong proponent of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) – identified the duals demonstration as a priority.

Box 2 provides a brief timeline of major milestones in the implementation of the One Care demonstration from April 2011 through 2014. After receiving a design contract from CMS in April 2011, Massachusetts began a multi-agency process in collaboration with a diverse set of stakeholders to develop a service delivery model that was submitted to CMS in February 2012. In June 2012, MassHealth initiated a Request for Responses (RFR) to gauge the level of interest among health plans in the state since a cornerstone of the demonstration was the formation of capitated managed care entities originally called Integrated Care Organizations, and now referred to as One Care plans. Ten health plans responded to the RFR. A committee comprised of state agency leaders and staff reviewed the plan responses and selected six plans to participate in ongoing discussions with the state. Plans also submitted an application to CMS. Massachusetts was also involved in extensive negotiations with CMS to finalize the financial and benefit elements of One Care. This process resulted in the MOU signed in August 2012. Under the terms of the MOU, CMS and the state are charged with jointly selecting and monitoring health plans that are participating in One Care. CMS’s aim for all demonstrations under the Financial Alignment Initiative, including One Care, was that the demonstrations should yield savings through better coordinated and more efficient care provision. Another consideration for CMS was developing rules and approaches that would be applicable across multiple state demonstrations. A key purpose of the demonstration is to test the effect of an integrated care delivery system and a blended capitated payment model for serving both community and institutional dual eligible populations in the state.

| Box 2: Implementation Timeline of Duals Financial Alignment Demonstration in Massachusetts |

|

In July 2013, three-way contracts were signed by CMS, Massachusetts, and each of the three participating health plans. By that stage, three of the initial six health plans identified through the Massachusetts RFR process had decided not to participate in One Care. A primary reason was concern about the upfront costs associated with building the infrastructure and developing the care delivery model, including a robust provider network sufficient to meeting the care needs of the dual eligible population, under the financial model agreed upon by the state and CMS in the August 2012 MOU. Many stakeholders noted that the decision not to join was a difficult one for these plans given the time they had invested in the effort and their commitment to the goals of the demonstration. After the three-way contracts were signed, the three participating plans – Commonwealth Care Alliance, Fallon Total Care, and Tufts Health Unify (formerly Network Health) – undertook a joint CMS/MassHealth readiness review process to prepare for the October 1, 2013 start date.

Certain dual eligible beneficiaries are excluded from One Care, including those with other comprehensive public or private insurance, those in an Intermediate Care Facility for people with Intellectual Disabilities, and Section 1915(c) home and community-based services (HCBS) waiver participants. Massachusetts beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage or the Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) may choose to participate in One Care if they disenroll from their existing programs. Multiple stakeholders expressed a hope that One Care would eventually be made available to HCBS waiver participants. There was some initial consideration of including this population. The MassHealth proposal to CMS included HCBS waiver participants and waiver services were intended to be wrapped into the demonstration. This population was later carved out in the MOU due to concerns by CMS about duplication of services and payment, and how to fully integrate care for this group of individuals with high service needs. Consumer advocates also expressed the view that it was better for HCBS waiver participants to be incorporated after the program had an established track record and any transitional issues were resolved. Advocates emphasized that HCBS waiver participants have very high levels of need for services and often rely on the waiver program to live independently in the community; therefore, any potential risks associated with the transition were of heightened concern among dual eligible beneficiaries in this group. One advocate also cautioned that rates would need to be reconsidered before extending the demonstration to HCBS waiver participants.

One salient feature of the One Care planning phase mentioned repeatedly across diverse stakeholders was the inclusiveness and the transparency of the process created by the leadership at MassHealth. Many stakeholders were particularly impressed with MassHealth’s approach to communication, information sharing, and participatory decision-making. One stakeholder noted that the public process in the planning of One Care was the most collaborative and transparent he had observed in his extensive policy experience, and viewed it as an impressive model case for effectively managing policy change. Box 3 summarizes key features of Massachusetts’ demonstration.

| Box 3: Highlights of Massachusetts One Care Duals Financial Alignment Demonstration |

|

One Care Financial Model

One Care plans receive a per member, per month global capitation payment intended to cover all costs of caring for One Care beneficiaries. This global payment, which blends Medicare and Medicaid funding streams, consists of three monthly capitation payments: one paid by CMS for Medicare Parts A and B services, which is risk adjusted using the CMS Hierarchical Condition Category (CMS-HCC) risk adjustment model used for Medicare Advantage plans6; a second paid by CMS for Medicare Part D prescription drug services, which is risk adjusted using the RxHCC model used for Part D plans; and a third paid by MassHealth, which is based on the beneficiary’s assigned rating category. One concern raised by numerous stakeholders was that the CMS portion of the rate based on the CMS-HCC and RxHCC models might not reflect the actual experience of the under-65 population served by One Care because CMS based its rate calculation on the entire dual eligible population, despite the fact that CMS-HCC and RxHCC models include age as a variable, which should result in the payments reflecting the variation in Medicare spending due to age.

When One Care was implemented in 2013, there were four MassHealth rating categories. The left panel of Box 4 summarizes these categories. Discussions with the One Care plans based on their initial experience, with input from key stakeholders, resulted in an expansion in the number of rating categories to address the fact that a subset of beneficiaries in the two higher community rating categories (C2 and C3) had particularly high costs. Beginning in 2014, those rating categories were further subdivided to account for those higher cost beneficiaries (see right panel of Box 4).7

| Box 4: One Care Rating Category Definitions | |

| 2013 One Care Rating Category Definitions | 2014 One Care Rating Definitions (Subdivided C3 and C2 Categories) |

|

F1 (facility-based care): used for individuals residing in a long-term care facility for more than 90 days

.

C3: used for individuals who have either a daily skilled need, two or more Activities of Daily Living (ADL) limitations AND a need for three days of skilled nursing care per week, or four or more ADL limitations .

C2: used for individuals with a chronic behavioral health diagnosis with a high level of service need

.

C1: used for individuals who do not meet criteria for F1, C3, or C2.

|

F1 (facility-based care): used for individuals residing in a long-term care facility for more than 90 days

.

C3 subdivided into 2 categories:

C2 subdivided into 2 categories:

C1: used for individuals who do not meet criteria for F1, C3A, C3B, C2A, and C2B. |

| SOURCE: One Care: MassHealth plus Medicare – January Enrollment Report, MassHealth. January 2014. Available at http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/masshealth/onecare/enrollment-reports/enrollment-report-january2014.pdf | |

Based on historical Medicaid claims data, a beneficiary is assigned to an initial MassHealth rating category. A beneficiary’s assignment can be changed using information from the beneficiary’s in-person Minimum Data Set – Home Care (MDS-HC) assessment, which must be completed by a registered nurse and may be performed in conjunction with the Comprehensive Assessment (see section on service delivery model). MassHealth rates reflect a prospective reduction based on an assumed savings level relative to historical claims. For October 1, 2013 through March 31, 2014, no savings were assumed. For April 1, 2014 through December 31, 2014, 1 percent savings were assumed. For the second demonstration year (January through December 2015), 0.5% percent savings were assumed, and for the third year (January through December 2016), 2% percent savings were assumed.8, 9 Demonstration savings amounts were amended from the original MOU reflecting an expectation of somewhat less savings than originally anticipated.

The terms of the three-way contract established that, for the first year of the demonstration, CMS and the state would share risk with the One Care plans as they transition to this global capitation arrangement.10 For subsequent years, there would be no risk sharing. When the terms of the contract were revised in September 2014, risk corridor protections were added for demonstration years 2 and 3. Additionally, to mitigate the financial risk assumed by the One Care plans throughout the demonstration period, the state uses two high risk pools for particularly high cost beneficiaries in the F1 and C3 rating categories in Years 2 and 3 of the demonstration.11

Finally, CMS and the state withhold a portion – 1 percent in the first demonstration year, 2 percent in the second, and 3 percent in the third – of the Medicare A/B and Medicaid capitation payments. One Care plans may earn back these funds if they meet certain quality standards specified in the contract (see section on performance standards). In year 1, plans are able to earn back withholds if they meet performance measurement standards, which are process-focused and oriented toward ensuring that One Care plans put basic care processes in place. In year 1 (which spans the period from the launch of One Care in October 2013 through December 2014), withholds are based on One Care plans establishing consumer governance boards, the share of new One Care beneficiaries with a completed initial in-person care assessment within 90 days of enrollment, and plan compliance with centralized beneficiary record requirements. In years 2 and 3, plan payment will be based on performance on the following nine quality withhold measures: (1) plan all-cause readmissions; (2) annual flu vaccines; (3) follow-up after hospitalization for mental illness; (4) screening for clinical depression and follow-up care; (5) controlling blood pressure; (6) Part D medication adherence for oral diabetes medications; (7) initiation and engagement of alcohol and other drug dependence treatment; (8) timely transmission of transition record; and (9) beneficiary-reported quality of life.12

Service Delivery Model

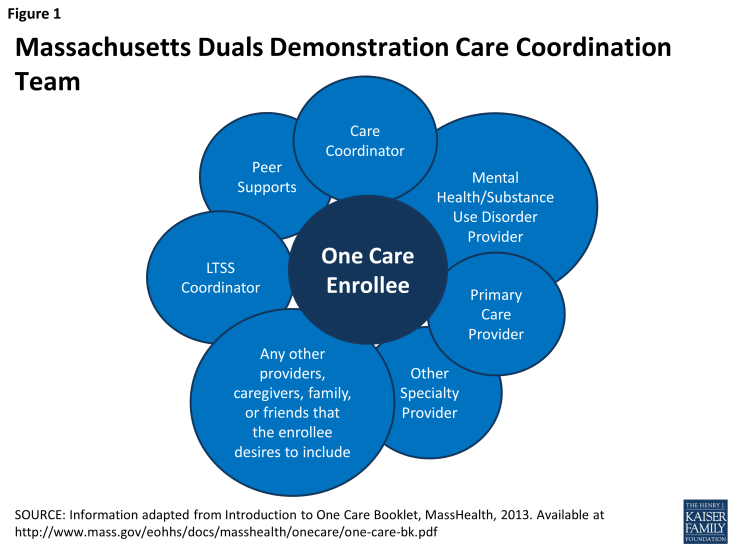

The One Care service delivery model was outlined in the February 2012 proposal submitted to CMS. Massachusetts engaged in an extensive process involving diverse stakeholders to develop a comprehensive benefit package that would be well-matched to the local environment and the needs of the One Care under-65 population with disabilities. The components of the service delivery model included an initial assessment followed by integrated services through a care coordination team including a care coordinator; primary care, behavioral health, and LTSS providers; an LTSS coordinator; peer support/counseling; other specialized service providers; and anyone else the beneficiary opts to include on the team (see Figure 1).

Initial Assessment

Once a beneficiary is enrolled in a One Care plan, the plan is contractually obligated to complete an initial face-to-face assessment of the beneficiary within 90 days of enrollment. Assessments must be conducted in the location of the beneficiary’s choosing, including their home if requested. The purposes of the initial assessment are to gather information about the beneficiary’s health care and support needs and to understand the beneficiary’s goals. More specifically, the assessment includes the following domains: (1) immediate needs and current services, including preventive health, preferred providers, what is working well for the enrollee and what can be improved; (2) health conditions; (3) current medications; (4) ability to communicate concerns or symptoms; (5) functional status, including ADL and IADL limitations; (6) mental health and substance use; (7) personal goals, including health goals and activities enjoyed and barriers to participating in those activities; (8) accessibility requirements and needs (e.g., specific communication needs such as language interpreters/translators, needs for personal assistance, appointment scheduling needs); (9) equipment needs including adaptive technology; (10) transportation access; (11) housing/home environment (e.g., risk of homelessness, home accessibility, home safety); (12) employment status and interest, including school and volunteer work; (13) involvement or affiliation with other care coordinators, care teams, or other state agencies; (14) informal supports/caregiver supports (e.g., children, spouse, parents); (15) risk factors for abuse and neglect; (16) leisure time and community involvement preferences, goals, and barriers; (17) social supports (e.g., peer support groups); (18) food security and nutrition; (19) wellness and exercise; and (20) advance directive/guardianship (e.g., health care proxy, power of attorney).

The One Care plan is responsible for this assessment, but can choose to subcontract it out to a provider to conduct. If completed by the One Care plan, these initial assessments are conducted by a One Care plan care coordinator, who is usually a nurse. Following this initial comprehensive assessment, additional assessments are required at least annually thereafter or whenever a beneficiary experiences a major change.

Once assessments began for individual members, it was noted by stakeholders that some beneficiaries needed to be placed in a higher rating category than the original assignment. In most of these cases, a beneficiary was originally categorized as a C1 rating category and needed to be switched to a C2. MassHealth confirmed this issue and paid plans for the difference between members’ assessed rating categories and proxy rating categories for up to 3 months prior to the date of assessment. One plan estimated that 20-30 percent of initial C1 assignments were later changed to C2s or C3s. A second One Care plan offered a somewhat higher estimate – about 40 percent of beneficiaries initially identified as C1s were determined to be C2s or C3s based on their assessments. In addition, several stakeholders reported that One Care plans had difficulty locating and scheduling individuals for the initial assessment, preventing timely rating category changes in some cases. As a way to address this issue, one plan reported utilizing pharmacy information, which tends to have the correct phone number and address for a beneficiary, to contact the beneficiary and complete the assessment.

Care Coordination

In the development of One Care, Massachusetts benefited from extensive experience with successful care coordination initiatives, albeit never before involving the under-65 dual eligible population. Consistent with One Care’s goal of the person-centered, coordinated approach, every beneficiary has a care coordinator who functions as a key member of the beneficiary’s larger interdisciplinary care team, illustrated in Figure 1. The care coordinator works with the other care team members and the beneficiary to create a Personal Care Plan.

Community Support Services

A major consideration was the need for One Care plans to develop a robust LTSS infrastructure to meet the needs of One Care beneficiaries since health plans did not have extensive experience delivering these services prior to the demonstration. Some stakeholders were critical of the fact that there were no explicit financial resources upfront or built into the capitation rate for these start-up activities. There was also concern that turning over LTSS to a managed care organization would decrease access to LTSS, and that health plans would not understand how to integrate these services into their benefit package.

In response, Massachusetts proposed to CMS inclusion of an LTSS coordinator in the service delivery model, structuring this position such that the coordinator would not be employed by the plan. One Care plans have entered into contracts with community-based organizations to staff the LTSS coordinator position under a variety of different financial arrangements. During the initial assessment and the development of the care plan, the beneficiary is offered the option of including an LTSS coordinator on the care team.

A lot of attention was paid to defining and outlining the role of the LTSS coordinator so that it could be clearly understood and well utilized by both plans and beneficiaries. As defined in the MOU, the LTSS coordinator is “contracted by the One Care plan with a community-based organization to ensure that an independent resource is assigned to and available to the Enrollee to assist with the coordination of his/her LTSS needs and to provide expertise and community supports to the Enrollee and his/her care team…and acts as an independent facilitator and liaison between the Enrollee, the plan and service providers.”13 The LTSS coordinator must be made available during assessments to all beneficiaries in the C3 (including C3A and C3B) and F1 rating categories and to beneficiaries in other categories who request it. The LTSS coordinator must also be made available: at any other time that a beneficiary requests; when the need for community-based LTSS is identified by the beneficiary or care team; if the beneficiary is receiving targeted case management, is receiving rehabilitation services provided by the Department of Mental Health, or has an affiliation with any state agency; or in the event of a contemplated admission to a nursing facility, psychiatric hospital, or other institution.14

The LTSS coordinator concept was frequently noted by stakeholders as a particularly challenging aspect of One Care planning and early implementation since this function is fairly new and uncharted territory for most stakeholders. Several stakeholders noted, for example, a concern about the beneficiary having too many coordinators, which could create service duplication and a need for a “coordinator for the coordinators.” In addition to concerns regarding duplication and inefficiencies, some initial capacity concerns due to insufficient numbers of coordinators and the potential for conflicts of interest to arise with coordinators employed by service agencies were noted. The contract specifically excludes most service agencies from providing this role, unless the One Care plan requests a waiver (for example, to address a network adequacy concern), and none of the One Care plans have requested waivers to date. On the other hand, the fact that One Care provides beneficiaries with coordinators who can counsel them and walk them through the process of receiving care has been described by consumer advocates as a major draw for beneficiaries to join. The potential of this role in providing an independent voice for beneficiaries on the care team was noted by consumer advocates. One stakeholder noted that the access to these care coordinators can help to lift the burden on informal caregivers as the beneficiary gains access to point people to assist with managing care.

Behavioral Health Services

MassHealth estimated that approximately 70 percent of beneficiaries eligible for One Care had a behavioral health diagnosis. Therefore, it was critical that One Care be designed to meet the behavioral health needs of beneficiaries. The structure of the care coordination team, as discussed above, automatically allows for an approach to care where physical and behavioral health services can be integrated in a capitated payment context. In addition, during the planning stages, Massachusetts worked to ensure that diversionary behavioral health services, including crisis stabilization; PACT (Program of Assertive Community Treatment); community support programs; partial hospitalization; acute treatment services and clinical support services for substance abuse; psychiatric day treatment; intensive outpatient services; structured outpatient addiction; and emergency services, were included in the One Care model (see Box 5 for Supplemental Diversionary Behavioral Health Services). These services had been previously available to other Medicaid beneficiaries in Massachusetts, so including them in One Care made the benefits available to the under-65 dual eligible population in line with the rest of the Medicaid program in the state. It was also critically important to consumer advocates that One Care embrace a recovery-oriented approach to behavioral health services. Beneficiaries can work with their care coordinator to gain access to community support programs and other services that enable beneficiaries to receive behavioral health care in the community.

Other One Care Supplemental Benefits

In addition to the services described above, One Care also offers expanded Medicaid state plan services: improved access to durable medical equipment, restorative dental services, and personal care including cueing and supervision. Additional services include respite care, care transitions assistance, home modifications (including installation), community health workers, medication management, non-medical transportation, and no copays for prescriptions (see Box 5). Several stakeholders noted that the fact that prescriptions do not have a copay under One Care has been a factor influencing the decision to voluntarily enroll in One Care, as are the more robust dental services and other benefits such as glasses and hearing aids.

| Box 5: Supplemental Benefits in the One Care Demonstration | ||

| Diversionary Behavioral Health Services: | Community Support Services: | Expanded State Plan Services: |

|

|

|

| SOURCE: Massachusetts’ Demonstration to Integrate Care and Align Financing for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries Executive Summary, Kaiser Family Foundation Policy Brief, October 2012, Available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/massachusetts-demonstration-to-integrate-care-and-align/ | ||

Enrollment in One Care

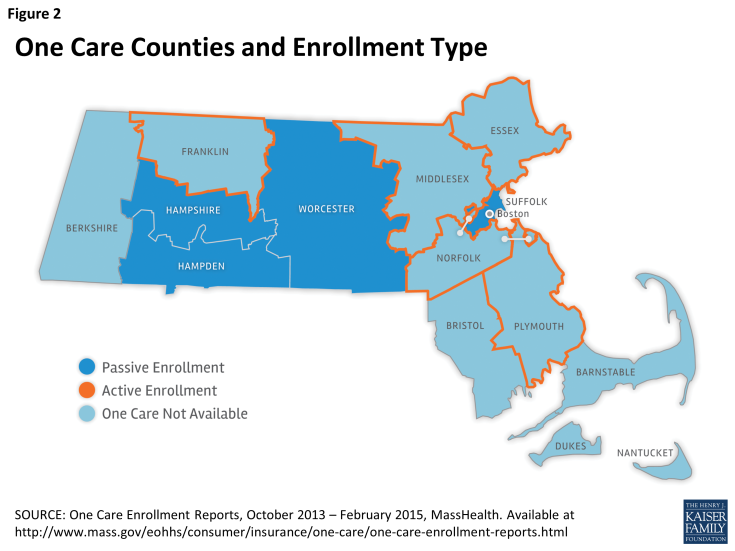

As noted above, in October 1, 2013, nine of fourteen Massachusetts counties began enrolling One Care beneficiaries (see map in Figure 2). In five of those counties (Essex, Franklin, Middlesex, Norfolk, and parts of Plymouth County) only one plan is operating and dual eligible beneficiaries can participate in the demonstration only through an active “opt-in” enrollment process.

In contrast, in the remaining four counties (Hampden, Hampshire, Suffolk, and Worcester) where there are 2 or more plans operating, dual eligible beneficiaries who have not opted out or selected a plan may be auto-assigned to a One Care plan; self-selection is also an option at any time. Enrollment changes – including plan switches – are effective on the first day of the following month.15 Individuals who opt-out have the opportunity to opt-in at any point in the future.

By February 2015, One Care had enrolled a total of 17,763 beneficiaries (or 18.4% of the estimated 96,449 state residents eligible for the demonstration), including both beneficiaries who opted in and those who were passively enrolled. To date, 26,792 individuals have opted out by either: (1) refusing passive enrollment (if they lived in a passive enrollment county); (2) proactively contacting One Care to say that they did not wish to participate (if they lived in an “opt-in only” county); or (3) enrolling and then subsequently disenrolling (all counties).

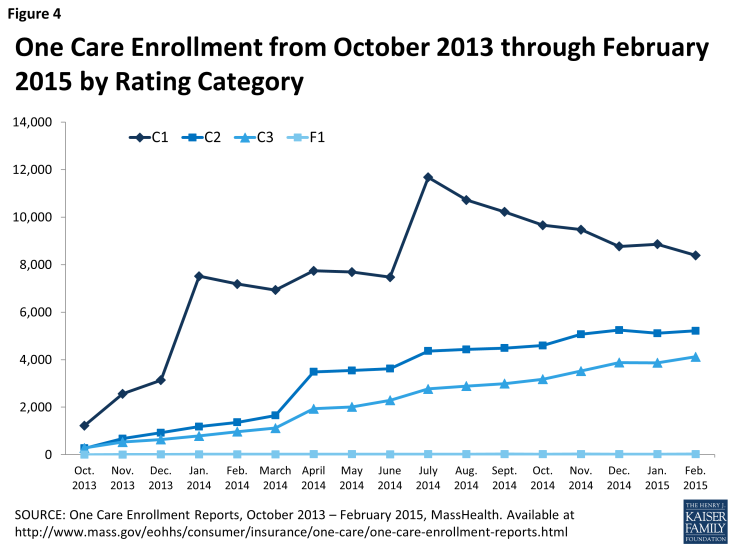

Figure 3 shows enrollment patterns by month overall and by plan. As Figure 3 indicates, two participating One Care plans have over 89 percent of One Care enrollment as of February 2015, in part as a function of the counties in which plans are participating, with 57 percent enrolled in Commonwealth Care Alliance, 32 percent enrolled in Fallon Total Care, and 11 percent enrolled in Tufts Health Unify.

Figure 3: One Care Enrollment Trends from October 2013 through February 2015 Overall and by One Care Plan

Of the 17,763 current One Care beneficiaries in nine counties across the entire demonstration, about 63 percent were enrolled through the passive enrollment process and the remaining 37 percent actively enrolled. In the four counties where beneficiaries are eligible for passive enrollment (due to having 2 or more plans operating in the county), 30 percent have enrolled (either passively or actively), 38 percent have opted out, and the remaining 32 percent have not yet been passively enrolled nor have they opted in/out and they remain eligible for future passive enrollment waves. Suffolk County, which includes Boston, the only passive enrollment county located in the eastern portion of the state, has the lowest opt-out rate (24%) among the four passive enrollment counties. In the five active enrollment counties (due to only a single One Care plan operating in the county), nearly 7 percent of dual eligible beneficiaries have actively chosen to enroll in One Care, another 18 percent have actively opted out (or actively opted in initially and then subsequently made the decision to opt out back to the FFS system), and the remaining 75 percent have stayed in the state’s FFS system. All One Care beneficiaries can opt out on a monthly basis. Beneficiaries who have opted out also have the option to subsequently opt-in on a monthly basis, if they choose. Beneficiaries enrolled in a One Care plan when they turn 65 who are still eligible for MassHealth under the State plan will be offered the choice of remaining in the demonstration, selecting a PACE or SCO plan if available, or returning to the FFS system.

Passive Enrollment

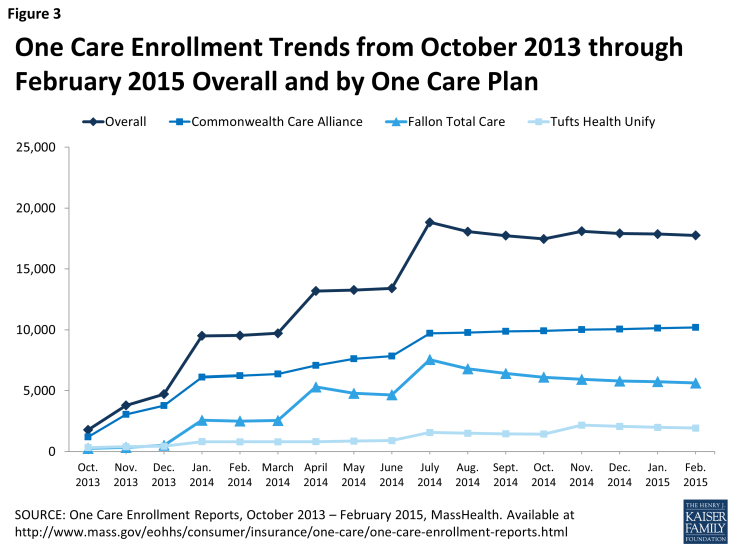

To date, there have been 4 passive enrollments: January, April, and July 2014, and one additional smaller round of passive enrollment in November 2014 focused on enrollment in a single plan – Tufts Health Unify. Unlike the other One Care plans, Tufts Health Unify did not take any passive enrollment beneficiaries in April 2014. This 4th round of passive enrollment is geared toward increasing the enrollment in this One Care plan to more closely match its initial enrollment projections. Figure 4 depicts monthly enrollment by rating category during over 17 months of the demonstration.

To conduct passive enrollment, MassHealth assigns beneficiaries to One Care plans using an “intelligent assignment” approach. First, MassHealth uses claims data to identify potential beneficiaries’ pre-existing provider relationships to enable, if possible, auto-assignment to a One Care plan that already contracts with a beneficiary’s care providers. This process was conducted by a passive enrollment assignment expert rather than a computer algorithm. For potential beneficiaries in the C1 category, passive enrollment plan assignment focused on matching a person to a One Care plan based on whether their primary care provider (i.e., a primary care provider with which the beneficiary had had at least 3 visits in the Medicaid claims data) was in a plan’s network. For potential beneficiaries in the C2 category, passive enrollment plan assignment focused on matching a person to a One Care plan based on whether both their primary care provider and behavioral health provider (i.e., a behavioral health provider with which the individual had had at least 5 visits in the Medicaid claims data) were in the plan’s network. Likewise, for potential beneficiaries in the C3 category, passive enrollment plan assignment focused on matching a person to a One Care plan based on whether their primary care provider and an LTSS provider (e.g., at least 5 visits to the same provider identified in Medicaid claims data) were in the plan’s network.

While stakeholders generally expressed the view that the intelligent assignment process had worked as intended, some provider and consumer stakeholders were critical of the passive enrollment process. The concern was that passive enrollment overwhelmed some plans as they struggled to locate large numbers of passively enrolled beneficiaries and complete the required initial assessments. One consumer advocate expressed the view that enrollment should have been conducted entirely on an opt-in basis. However, passive enrollment was viewed as necessary among others interviewed to give the One Care plans an influx of revenue and to build the infrastructure for robust care coordination and other service delivery functions. One health plan commented that a passive enrollment approach where the beneficiaries were assigned monthly, rather than quarterly, might have helped “smooth out” the bolus of beneficiaries coming to the plans on a quarterly basis and helped with engagement and planning for their needs. Another stakeholder noted that the pressure passive enrollment placed on the system stood in the way of a more thoughtful implementation of the new LTSS coordinator function. Some stakeholders cited the challenges associated with maintaining beneficiaries’ existing provider relationships as the reason for not joining One Care, and others noted both fear of change and wait-and-see attitudes among dual eligible beneficiaries opting not to join.

Public Awareness and Marketing of One Care

Public outreach to potential beneficiaries began in July 2013, and marketing for the program by health plans began in September 2013. One Care plans were required to receive prior approval for certain categories of marketing and beneficiary communication materials from CMS and Massachusetts. The state held multiple public informational meetings in different regions over the period of July 2013 to October 2013. For beneficiaries eligible for passive enrollment, the state mails 60- and 30-day notices informing beneficiaries about their upcoming assignment to a One Care plan and notifying them of their rights to actively select a different plan or to opt out of the demonstration. A series of workgroups with both state agency staff and extensive stakeholder participation were held to develop member notices. For example, the Department of Mental Health was consulted on materials to ensure that the language used was inclusive and recovery-oriented. With these notices, eligible beneficiaries also receive an enrollment guide and an enrollment decision form. The state did not include an online enrollment option; beneficiaries could enroll either by mailing in their application or by phoning MassHealth.

The state acknowledged early challenges in terms of ensuring that eligible beneficiaries were aware of One Care. Specific concerns noted included incorrect addresses on file, difficulties associated with contacting dual eligible beneficiaries who were homeless or at risk for homelessness, and challenges explaining the benefit differences between One Care and their current plan to PACE or Medicare Advantage plan beneficiaries. The SHINE Program (Serving Health Insurance Needs of Everyone), a state health insurance assistance program that provides free insurance counseling and is administered by the Massachusetts Executive Office of Elder Affairs and partially funded by CMS, played a key role in assisting eligible beneficiaries in understanding their One Care enrollment options. SHINE, a volunteer organization, already had extensive experience operating in the state training volunteers to advise elders about their Medicare plan options. While SHINE volunteers were able to connect with potential beneficiaries in whatever setting was most preferred (e.g., at home, at a community center, by phone), in practice, most of the navigation-related meetings for One Care were conducted by phone. SHINE noted a concern among advocates that its organization lacked experience initially with issues important to non-elderly persons with disabilities, and trainings were used to help prepare volunteers to address the concerns of One Care eligible individuals. Outreach focused on highlighting new services available to beneficiaries, including care coordination and dental and vision benefits, to showcase advantages of joining One Care. MassHealth also focused on reaching out directly to beneficiaries as much as possible through meetings and forums at locations around the state convenient to potential beneficiaries, and emphasized the importance of word-of-mouth. Another challenge from a marketing perspective was that One Care was being implemented at the same time that multiple other ACA initiatives were being rolled out, causing some confusion on the part of potential beneficiaries. Interviewees were not aware of any campaigns or other efforts designed to discourage beneficiary enrollment in One Care as has occurred in other states.

A number of early communications challenges have been addressed with the development of additional materials and approaches. For example, one issue that arose related to timing of disenrollment notices for the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit. When One Care initially started, beneficiaries included in auto-assignment often received a disenrollment notice from their current Part D plan before receiving enrollment information about the demonstration. While the Part D disenrollment did not take effect until after the One Care enrollment effective date, the timing of the notices created confusion and concern among beneficiaries. SHINE counselors worked to educate beneficiaries and provided feedback to the state about this issue. In subsequent rounds of auto-assignment, the state and CMS worked to time the demonstration enrollment notices such that they would reach beneficiaries around the same time as the PDP disenrollment notices. SHINE feedback, along with feedback from beneficiaries, advocates, and stakeholders, led to the development of a new “One Care Covers Prescription Drugs” insert included in the March 2014 enrollment packet mailing with information about Medicare Part D benefits in One Care.

Efforts to continue to boost enrollment in One Care are ongoing. Recently, for example, video vignettes were developed by consumer groups to share beneficiaries’ personal experiences with One Care and to continue to raise awareness among dual eligible beneficiaries about One Care as an option.

Provider Involvement

Each One Care plan must demonstrate on an annual basis that an adequate provider network is in place to meet the medical, behavioral health, pharmacy, community-based services, and LTSS needs of its One Care beneficiaries, and to ensure physical, communication, and geographic access. One Care plans reported working hard to develop One Care provider networks with a broad range of medical, behavioral health, and LTSS providers. The Massachusetts demonstration contract, like all of the demonstration contracts, has requirements related to compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). MassHealth requires One Care plans to contract with providers that demonstrate their commitment and ability to accommodate the physical access and flexible scheduling needs of beneficiaries.16 In practice, this means One Care plans must have a designated ADA compliance officer related to the demonstration and a work plan to ensure physical access to buildings, services, and equipment under the MOU. One Care plans are also required to develop and provide continuing education programs for their provider network related to ADA compliance, accessibility, and accommodations.

The One Care plan contracts also include detailed network adequacy requirements to facilitate beneficiary continuity of care.17 In particular, One Care plans were required to gain approval of their provider network as a part of the readiness review process, and they were required to meet or exceed the network adequacy requirements of Medicare and MassHealth. One important area where continuity of care has been an issue has been primary care. While One Care plans were often able to identify a beneficiary’s primary care provider through Medicaid claims, some stakeholders noted that it was problematic that this information was not collected through the One Care enrollment form. In some cases, One Care plans have reached out to provider organizations that have not wanted to join the One Care networks or have opted for an exclusive network with a single plan. In other cases, providers have reached out directly to One Care plans to request to join the network upon finding they had a patient who had been enrolled.

Many of these negotiations involve new contracting partnerships under One Care. Examples include new contracts with a large vendor for transportation and contracting with other community-based organizations for day programs and adult foster care. One Care plans described extensive time and efforts invested in helping external organizations to understand the care coordination model through various training and education activities. One Care plans have also added new personnel, including outreach workers and psychiatric nurse practitioners, to their care coordination teams. One Care plans are required to offer single-case out-of-network agreements to providers with pre-existing care relationships with dual eligible beneficiaries if they are not willing to enroll in the One Care plan’s provider network but willing to continue serving beneficiaries based on the plan’s in-network rate of payment. However, in practice, one stakeholder noted that single-case arrangements tended to be difficult in Massachusetts since providers were often organized into larger groups.

Beneficiary Engagement

Massachusetts has a long tradition of high level beneficiary engagement in health care initiatives. Beneficiary engagement in the design and implementation of One Care has been a hallmark of the demonstration, and has occurred at numerous levels. The state has well-developed disability and behavioral health consumer advocacy communities, and state leaders were open to actively engaging in discussions and some decision making with these community-based consumer advocacy partners. MassHealth brought beneficiary stakeholder organizations to the table early in the planning process to be involved in key decisions about the demonstration including the design of the service delivery model, the structure of oversight and monitoring, and the grievance and appeals process. During the program design stage, the state sought input on the integrated care model from both cross-disability and disability-specific consumer perspectives. In 2011, for example, MassHealth conducted four focus groups with a total of 40 dual eligible beneficiaries to achieve diversity in perspective by geographic location and primary language of beneficiaries. Massachusetts also conducted a series of state agency and external consumer group outreach sessions with dual eligible beneficiaries with specific disabilities (e.g., mental health disabilities, developmental disabilities, physical disabilities) in 2011.18 Multiple stakeholders noted that this process was essential to shaping the design of the state’s care delivery model and demonstration proposal to CMS. For example, based on feedback related to frustrations that mailings and other official information were confusing, too long, and often duplicative, MassHealth emphasized working with stakeholders to improve plan communication with beneficiaries. Similarly, in response to dual eligible beneficiary concerns about limited access to dental services in the state, MassHealth expanded those services under the demonstration.

An Implementation Council was established by MassHealth and charged with monitoring program access and quality, promoting transparency in program implementation, and assessing ADA compliance. The council has up to 21 members and receives support from MassHealth’s contractor, University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS). The Implementation Council members were identified through an open nomination process. The Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services (EOHHS) convened a team of agency staff to evaluate the nominations and recommend to the Director of MassHealth and the Secretary of EOHHS a slate of nominees to appoint to the Implementation Council. At least half of the slots are required to be filled by MassHealth beneficiaries with disabilities or their family members,19 and the remainder of slots were filled by representatives of hospital, provider, collective bargaining and advocacy organizations. The Implementation Council is led by a Chair and two Co-Chairs (selected by the Council), and holds monthly meetings that are open to the public. Formal feedback is provided to the state on how implementation is progressing and whether any specific issues need to be addressed. The Implementation Council was established during the early planning stages, and both the state and the Council saw the value of continuing the involvement of this group. One Care plans have also convened their own beneficiary advisory bodies with the goal of obtaining first-hand information on how the program is working and areas for improvement. One plan described sending out notices in the counties in which it operates inviting beneficiaries to be involved with its beneficiary council and providing transportation to attend council meetings. These meetings were described by the One Care plan as very well attended, with caregivers and consumer advocates often in attendance.

In October 2013, the Implementation Council along with MassHealth and UMMS formed the Early Indicators Project (EIP) workgroup, which aims to monitor, analyze, and report on beneficiaries’ early experiences with One Care.20 The Early Indicators Project – a separate research effort from the CMS-initiated evaluation – gathers data using a variety of methods and sources, such as focus groups, surveys, enrollment data, and feedback from SHINE and the One Care plans, in order to get a sense of overall member experience and why beneficiaries opt in or out. More indicators will be added in the future. This information is available on the MassHealth website, where EIP information, including monthly enrollment data, monthly MassHealth Customer Service Team activity reports, focus groups and survey reports, and general quarterly reports, is posted.21

In addition, an Ombudsman program was established in March 2014 to help One Care beneficiaries address concerns or conflicts and acts as a bridge between beneficiaries and the Executive Office of Elder Affairs. The Ombudsman was selected through a RFP process, and the office officially opened in March 2014. The Ombudsman program is made up of two partnering organizations: the Disability Policy Consortium and Health Care for All. The program manages a network of oversight functions with regional, language-based, and disability-based capabilities. The Ombudsman program interacts with the Implementation Council and gives presentations for various work groups and committees. To date, a primary issue brought to the Ombudsman program has been One Care plans providing initial assessments in a timely manner. While many One Care beneficiaries were frustrated by timeliness concerns, it appears that only a very small number dropped out of One Care due to this issue. At this stage of the demonstration, it is too early to determine whether beneficiaries were experiencing challenges in navigating the demonstration’s appeals process for One Care plan decisions about service authorizations, as very few beneficiaries had initiated appeals. As One Care moves into demonstration year 2, a broader issue relates to what kinds of tools the Ombudsman program can use to address beneficiary concerns beyond reaching out to specific plans to discuss concerns and complaints brought to the Ombudsman by beneficiaries.

Performance Measurement and Achieving Outcomes

Quality Metrics and Reporting

Under the terms of the August 2012 MOU, One Care plans are required to report 104 core quality metrics under the demonstration related to access and availability, care coordination/transitions, health and well-being, behavioral health, patient and caregiver experiences, screening and prevention, and quality of life. Some of these are CMS core measures (i.e., standard Medicare Advantage and Medicare Part D plan measures), some are Massachusetts-specific measures, and some are both. These include reporting of National Committee for Quality Assurance/Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (NCQA/HEDIS), Health Outcomes Survey (HOS), and Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) measures, and plan performance related to LTSS. A subset of these core measures is used for calculating withhold payments in each of the three demonstration years (see description in One Care Financial model subsection above). One common theme across multiple stakeholder interviews was the large number of required measures; with over one hundred different measures One Care plans were charged to report on, there was some skepticism about how much attention plans would feasibly be able to pay to improvements within a single measurement domain. A second concern related to the appropriateness of included measures as good indicators of whether the care needs of beneficiaries were being met by One Care. A few stakeholders, for example, noted the dearth of good performance metrics in the behavioral health area, and that the most commonly used measures were not particularly well-suited to assessing the quality of behavioral health care being provided to dual eligible beneficiaries in One Care.

Outcomes and Evaluation

Savings from the demonstration are expected to result primarily from reductions in emergency department and inpatient use on both the behavioral health and medical side. State agency and health plan leaders viewed care coordination and greater reliance on intermediate levels of care as key to achieving such reductions. A number of evaluation approaches are being used to assess whether the demonstration is successful in achieving these and other important outcomes. First, MassHealth has been actively engaged in ongoing internal tracking and reporting since initiation of the demonstration to evaluate the impact of the demonstration. The primary data on One Care available to date has come from four focus groups and a consumer survey conducted through the Massachusetts EIP. While these data provide some early insights, they are not designed to provide a comprehensive assessment of how well the demonstration is meeting its goals. Second, CMS has contracted with an independent evaluator to assess the effects of all of the state dual eligible demonstrations, including One Care, on cost, quality, utilization, and beneficiary experiences with care. This evaluation will use a mixed-methods approach to capture both qualitative and quantitative information on the impact of demonstration activities. Qualitative methods will include analysis of site visit, focus group, and key informant interview data. Quantitative analyses will evaluate the impact of the broader demonstration, including calculation of the savings attributable to the demonstration using a comparison group approach.22

One tension that has emerged as One Care moves forward has been the intense interest among beneficiaries and consumer advocates in obtaining an early picture of the performance of the demonstration and the reality that even preliminary quantitative assessment of how the program is impacting key dimensions including quality of care, costs, and beneficiary well-being is still years away. None of the stakeholders interviewed expected that it would be possible to understand the impact on inpatient and emergency department use and spending until the demonstration has been in place for another year or more.

Specific concerns related to achieving measureable reductions in inpatient and emergency department costs included whether the rates would be sufficient to cover the comprehensive One Care service benefit package and lack of up-front funding to cover the development of new infrastructure needs, particularly in the area of crisis stabilization services, to keep beneficiaries out of the inpatient setting. With regard to the rates, several stakeholders noted that it was too early to determine whether the risk adjustment approaches used for both the Medicaid and Medicare portions of the capitation rates will be sufficient to adequately account for variation in costs across beneficiaries. A concern was noted, for example, about whether the C2 negotiated rates were high enough to cover the costs of caring for individuals with chronic behavioral health conditions. With regard to new infrastructure, One Care plans noted the difficulty of funding the upfront costs of building the infrastructure needed to support the model under the current rates, even if the rates might ultimately be sufficient to cover the costs of care after the infrastructure is in place. There was recognition on the part of both the state and the One Care plans that the model should only be implemented (at least initially) in counties with a sufficient number of dual eligible beneficiaries to most effectively target infrastructure development. Two different stakeholders noted that crisis stabilization service capacity for beneficiaries with acute medical or behavioral needs was limited in most One Care communities, and, without expanding this capacity, beneficiaries who needed crisis stabilization would end up being placed in more costly inpatient beds, threatening the viability of the financial model.

Looking Ahead

Observations about the early implementation phase of One Care – the first dual eligible capitated financial alignment demonstration to be implemented in the country – can provide important insights for other states as they move their demonstrations forward. Massachusetts stakeholders interviewed noted various challenges including gaining robust health plan participation under terms of the financing arrangement negotiated by CMS and the state, passive enrollment-related issues including tracking down reliable contact information on new beneficiaries and completing timely face-to-face assessments during these waves of large influxes of new beneficiaries, identifying new beneficiaries’ key provider relationships to either match them to a One Care plan or actively recruit them into a provider network, and developing and refining the capitation rates and risk adjustment approach. Additional challenges included implementing the role of the LTSS coordinator and forming plan provider networks with adequate primary care, behavioral health, and LTSS access to meet the needs of the One Care population in a manner consistent with the state’s care delivery model. While transitional issues inevitably arise with any new program, consumer advocates stressed the risks these transition issues posed to the vulnerable population of dual eligible beneficiaries in Massachusetts who are dependent on a well-functioning care team to attain their independent living goals.

Interviews with stakeholders also identified numerous strengths of the One Care planning and implementation. Stakeholders noted the state’s encouragement of a robust stakeholder process, and the role of passive enrollment in ensuring sufficient enrollment to ease financial uncertainty for participating plans. Many stakeholders across diverse perspectives noted the leadership from the key state agencies, in particular MassHealth, in guiding design and implementation of One Care in an open-minded, participatory, and transparent manner. One provider stakeholder remarked on never having seen the state engage in such a thoughtful, open planning process for a new initiative, and that this philosophy had been carried into the implementation phase with well-attended monthly public One Care meetings and Implementation Council meetings during which detailed enrollment status information is shared and stakeholder input is solicited.

The Massachusetts experience with the dual eligible financial alignment demonstration raises some general questions about how to most effectively move vulnerable populations into a capitated payment system and integrate Medicaid and Medicare financing. In Massachusetts, the benefits of enhanced care coordination and more flexible use of dollars have been immediately apparent for some as beneficiaries gained access to new services and a range of new care coordination functions. It will take longer to evaluate the impact of other key aspects of the One Care implementation. For example, it will be important to assess how the multi-phased passive enrollment process undertaken in Massachusetts compares to a slower active enrollment process. Likewise, it will be critical to reflect on the initial goal of state-wide participation in the One Care program given the major care delivery infrastructure investments needed to get the demonstration off the ground. There are no plans in place for extending One Care to the five counties not currently participating in the demonstration. One stakeholder noted that, in spite of the original state-wide aspirations for the program, One Care had been implemented in a manner more in line with the spirit of a demonstration and stressed the upsides of slower regional expansion. Finally, assessment over time of the viability of the financial model to support the comprehensive package of services under One Care will be needed, and it will be critical to determine whether better coordination and a flexible service delivery model can lead to lower inpatient and emergency department costs and improved care quality.

In summary, stakeholder interviews conveyed a general sense of cautious optimism about the potential for the demonstration to transform care for the dual eligible population in Massachusetts. While stakeholders expressed concerns about certain aspects of the One Care implementation, there was broad agreement that the existing system had not been serving beneficiaries well, and the moment was right for investment in improving the care delivery and financing model serving the Medicare and Medicaid dual eligible population in Massachusetts.

This issue brief was prepared by Colleen Barry of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Lauren Riedel, Alisa Busch, and Haiden Huskamp of Harvard Medical School.