Early Insights From Ohio’s Demonstration to Integrate Care and Align Financing for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries

Introduction

In May 2014, Ohio launched a financial alignment demonstration for dual eligible beneficiaries, known as MyCare Ohio. Ohio is one of twelve states to receive approval by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to develop a service delivery and payment model to integrate care for beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. The objectives of the demonstration are to deliver person-centered, higher quality care, to better coordinate care across all settings (physical, behavioral and long-term services and supports (LTSS)), to promote independence in the community, and to eliminate cost shifting between Medicare and Medicaid. The results of these efforts have the potential to translate into better health outcomes for beneficiaries and savings across both programs. At the same time, changing delivery systems can risk disrupting care for these high need vulnerable beneficiaries. For more information about the demonstrations, see Box 1.

| Box 1: Financial Alignment Demonstrations for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries |

| Under new authority in the Affordable Care Act, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is testing capitated and managed fee-for-service models as a way to align Medicare and Medicaid benefits and financing for dual eligible beneficiaries with the goal of delivering better coordinated care and reducing costs. The three-year demonstrations, implemented beginning in July 2013, are introducing changes in the delivery systems through which beneficiaries receive medical and long-term care services. They are also changing the financing arrangements among CMS, the states, and providers. As of July 2014, seven states had begun enrolling beneficiaries in their demonstrations. For more information see: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/financial-alignment-demonstrations-for-dual-eligible-beneficiaries-compared. |

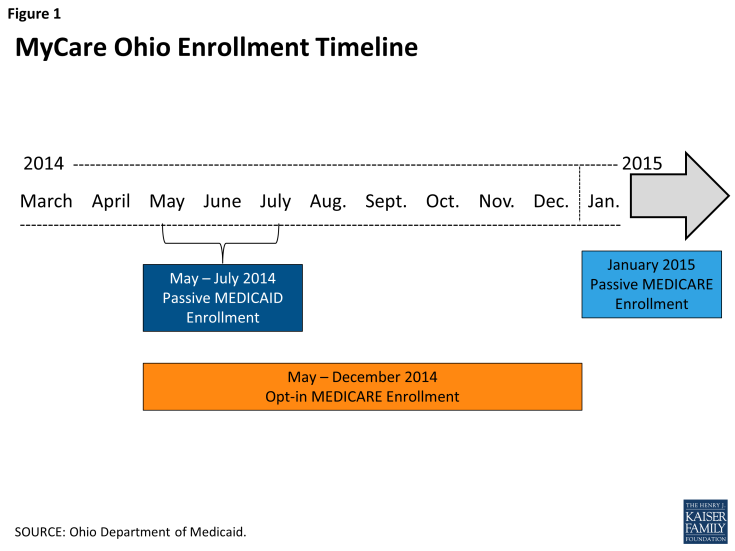

Unlike demonstrations in other states, Ohio concurrently implemented mandatory Medicaid managed care and the financial alignment demonstration. First, beneficiaries were automatically assigned to plans and enrolled in mandatory Medicaid managed care. During this time, enrollment in the financial alignment demonstration (including Medicare services) was voluntary for dual eligible beneficiaries. Next, Ohio automatically assigned remaining dual eligible beneficiaries to health plans for purposes of their Medicare benefits, effectuating their enrollment in the financial alignment demonstration. This issue brief focuses on the first phase of MyCare Ohio implementation, mandatory Medicaid managed care enrollment with optional enrollment in the financial alignment demonstration for Medicare benefits. It does not report on the integration of both Medicare and Medicaid benefits for the vast majority of participants following Medicare passive enrollment in January 2015. The results of this case study can inform the implementation of financial alignment demonstrations in other states over the coming months, as results from CMS’s evaluation of the demonstrations are not expected to be available for some time.

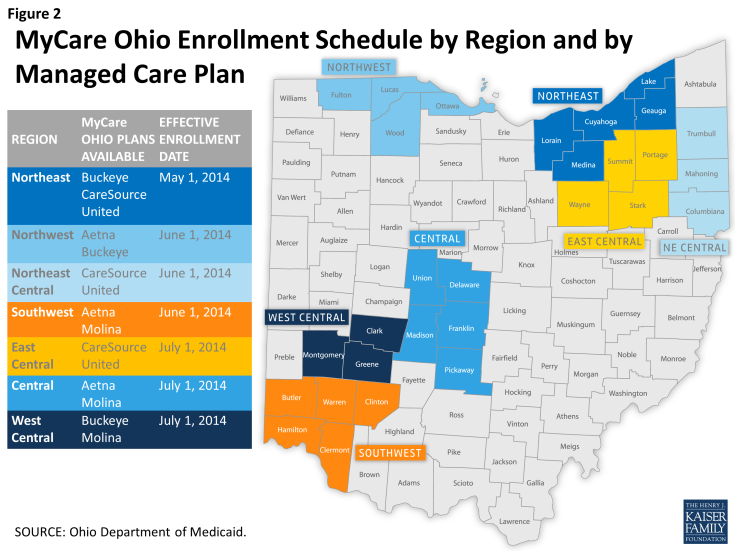

Ohio was the third state, behind Massachusetts and Washington,1 to receive approval to test a financial alignment model. In December 2012, CMS and the state signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU). Originally set to launch in 2013, enrollment in Ohio’s demonstration was repeatedly delayed due to the complexities involved with launching a new program. The demonstration continues for a 3-year period and ends on December 31, 2017. Ohio’s financial alignment demonstration targets an estimated 115,0002 dual eligible beneficiaries (62% of all duals) in 29 (of 88) counties, grouped into 7 regions. The regions are centered on major metropolitan areas across the state (Columbus, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Toledo, and Dayton). In each region, the state has contracted with two managed care plans (in the Cleveland region, there are three plans) to provide beneficiaries with choice among plans.

Mandatory enrollment for Medicaid benefits began on May 1, 2014 in the northeast region followed by three regions each on June 1 and July 1 (Figures 1 & 2). As part of the Medicaid enrollment process, individuals could choose to enroll in the same MyCare plan for Medicare services or choose to keep their current Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) or Medicare Advantage plan. In October 2014, notices were sent out to beneficiaries informing them that their health care is changing, and that effective January 1, 2015, they would be enrolled for Medicare benefits in the plan from which they were already receiving their Medicaid benefits, unless they made an alternative election. Dual eligible beneficiaries who choose to enroll in the demonstration for their Medicare benefits have the option of switching health plans and can opt out/into a plan for Medicare services at any time, but they must continue to receive Medicaid services through a MyCare plan.

Ohio’s financial alignment demonstration is comprehensive in scope of populations covered and services offered. Populations covered under the demonstration include most dually eligible individuals over the age of 18, including seniors and adults with physical disabilities and behavioral health needs. The demonstration benefits package includes all benefits available through the Medicaid and Medicare programs, including LTSS (both institutional and HCBS) and behavioral health services.

Two distinct features of Ohio’s financial alignment demonstration set it apart from the MA and VA demonstrations. They are the fact that Medicaid managed care enrollment is mandatory (individuals can only opt-out for Medicare benefits) and that the demonstration enrollment process was bifurcated, for most beneficiaries, so that mandatory enrollment happened first for Medicaid benefits and six to eight months later for Medicare benefits. Another unique feature of Ohio’s demonstration is the requirement that plans work with the Area Agencies on Aging (AAAs) and other entities that have experience working with people with disabilities (e.g. Centers for Independent Living and disability-oriented case management agencies, etc.) to provide home and community-based waiver service coordination for individuals age 60 and over.

Methods

This issue brief examines how managed care plans, the state, providers and beneficiary advocates/stakeholders experienced the planning and early implementation of Ohio’s financial alignment demonstration. Goals of the research were to: examine the transition to an integrated managed care benefit for Medicare and Medicaid; identify challenges faced during the first six months of the demonstration and strategies that were employed to deal with certain challenges; and inform other states pursuing financial alignment arrangements for dually eligible beneficiaries. Forty-four stakeholder interviews were conducted between August and December of 2014 with MyCare Ohio plans, Ohio Department of Medicaid (ODM) officials, providers (medical, behavioral health, and social services), and advocacy organizations/beneficiary representatives. Interviews occurred in person and over the phone and included representatives from all seven MyCare Ohio regions. The first round of interviews occurred just one to three months following the phased-in implementation of MyCare Ohio, and therefore represents perspectives on the planning process and initial perspectives on the demonstration rollout. Subsequent interviews over the next several months sought opinions on the demonstration over the course of the first six months. Follow-up interviews were conducted with select stakeholders in early December to assess any changes in initial impressions and perspectives leading up to passive Medicare enrollment in January 2015. The brief was supplemented with data provided by ODM and by reviewing public documents related to MyCare Ohio on the state Medicaid agency and CMS websites.3

Key Planning and Program Features

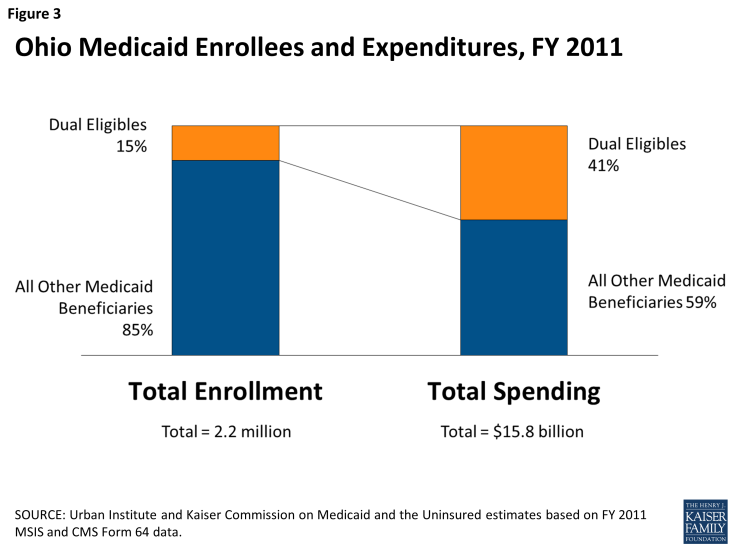

Like other states across the country, Ohio experienced budgetary challenges during the most recent economic downturn. The state was facing an $8 billion shortfall over the 2011-2013 biennium, and Medicaid costs were increasing nine percentage points per year, according to ODM officials. Governor Kasich’s administration made slowing the growth of Medicaid spending a priority, and plans to modernize Medicaid included prioritizing HCBS over institutional care and integrating Medicaid and Medicare benefits. The financial alignment demonstration was an opportunity to have all physical, behavioral and LTSS benefits fully coordinated and capitated under one system for dual eligible beneficiaries. The state viewed the demonstration as an opportunity to develop more integrated ways to pay for and deliver services to some of the poorest and sickest beneficiaries covered by either program. They are also some of the costliest. In 2011, 15 percent of Ohio’s Medicaid beneficiaries who are also eligible for Medicare accounted for 41 percent of spending for Medicaid services (Figure 3). Seventy-five percent of this spending was for LTSS, including nursing facility and HCBS.4

To be eligible for Ohio’s financial alignment demonstration, an individual must be eligible for all parts of Medicare (Parts A, B and D) and be fully eligible for Medicaid; over the age of 18; and reside in one of the demonstration counties. Certain dual eligible beneficiaries are excluded from MyCare Ohio, including individuals under age 18; individuals with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (I/DD) who are receiving services through an I/DD home and community-based services (HCBS) waiver or Intermediate Care Facility (ICF)-I/DD; individuals who are eligible for Medicaid through a delayed spend-down; individuals who have creditable third party insurance including retirement benefits; individuals enrolled in the Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), and individuals participating in the CMS Independence at Home Demonstration. ODM officials noted that a goal from the early planning stages was to “include as many people as possible because we believe care coordination is the best way to go.” Ultimately, according to ODM officials, certain groups were excluded either because their care coordination was “happening fairly well already” (I/DD population) or due to the complexity involved with coordinating with third party insurance.

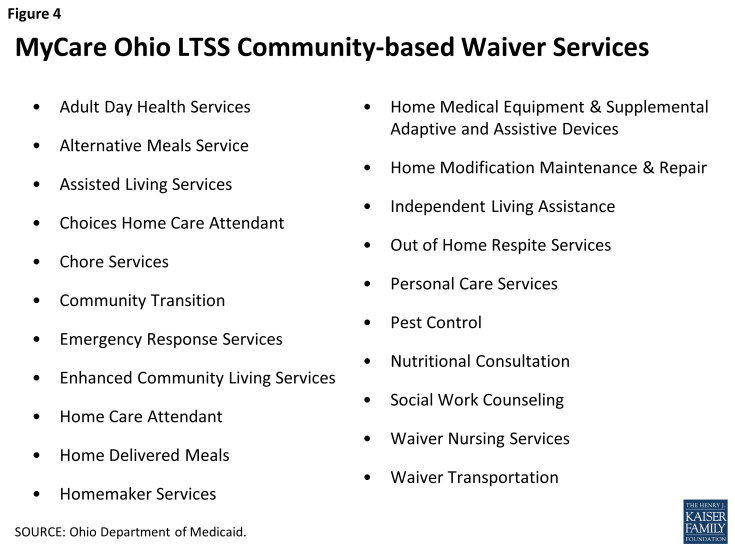

The demonstration’s benefits package includes all benefits available through the Medicare and Medicaid programs, including LTSS and behavioral health services. Exceptions include Medicare hospice and Medicaid habilitation services, targeted case management, and institutional and home and community-based waiver services for individuals with I/DD. Plans have discretion to offer enhanced benefits, for example, expanded Medicaid state plan benefits such as transportation or dental services. Ohio needed Medicaid managed care authority to operationalize the model for MyCare Ohio because the state was not already delivering Medicaid benefits for dual eligible beneficiaries through capitated managed care. Prior to MyCare, a limited number of dual eligible beneficiaries were enrolled in managed care through the PACE program, while the vast majority (74%) of managed care enrollment in Ohio is made up of children and families. Adults with disabilities (non-duals) account for about 7 percent of the over 2 million individuals enrolled in managed care. Independent of its financial alignment demonstration authority, Ohio obtained a new § 1915(b)/(c) Medicaid managed LTSS waiver that encompassed all of Ohio’s five Medicaid § 1915(c) HCBS waivers where participation was dependent on the beneficiary having level of care (LOC) needs equivalent to that required for Medicaid nursing facility coverage.5 Beneficiaries enrolled in the new waiver saw their services expand to include homemaker and home care attendant services – services not previously offered under each HCBS waiver (Figure 4). The new Medicaid managed care waiver also allows beneficiaries to continue self-direction of services. Meanwhile, some waiver populations now have access to services such as nursing services and respite services that previously only were available to certain other waiver populations.

Health Plans Participating in the Demonstration

In February 2014, three-way contracts were signed by CMS, Ohio, and each of the five participating health plans (Aetna, Buckeye (owned by Centene), CareSource, Molina and UnitedHealthcare). CareSource is the only non-profit health plan out of the five MyCare plans, but has partnered with the for-profit company Humana for the financial alignment demonstration.6 The plans were selected through a competitive process designed to assure plans had the experience necessary to meet the needs of dually eligible beneficiaries. Based on rankings from the bidding process, each of the plans was allowed to choose three of the seven regions in which to participate. In each region, two of the plans are available (the Cleveland region has three plans). Four of the five plans had experience with Medicare Advantage Special Needs Plans (SNP) in Ohio. About 11,000 dual eligible beneficiaries were enrolled in SNPs in Ohio in 2014, which is roughly 4% of the total dual eligible population. Four of the five plans were previously serving Medicaid beneficiaries, including children and parents as well as adults and children with disabilities (non-duals). In Ohio 77 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries (or more than 2.1 million people) are enrolled in a managed care plan.7 None of the financial alignment demonstration plans, however, had prior experience with managing HCBS in Ohio. The plans reportedly relied on national experience serving HCBS populations in other states to handle the new service delivery piece, essentially the waiver program, that most demonstration participants rely on to meet their LTSS needs. The plans also largely leaned on the AAAs and local companies that provide home and community-based case management services to develop experience. One of the biggest learning curves plans mentioned was readying their systems to process waiver and nursing facility claims.

A provider agreement between ODM and the managed care plans was signed in February 2014 and amended effective January 1, 2105. The agreement sets forth a number of requirements including call center, staffing, financial reporting, provider contracting, marketing, benefits, and payment requirements. In the agreement, the managed care plans agree to assume the risk of loss, while complying with federal and state laws, and the agreement also specified actuarially sound capitation rates. Lastly, the agreement consists of certain components aimed at incentivizing plans that improve health outcomes.8

“The process of integrating the Medicare and Medicaid programs from a systems standpoint and a programmatic standpoint…people say this is one of the most complicated things they have done in their careers.”

– State Official

Prior to enrollment, each plan underwent a joint CMS/state readiness review to ensure the plan’s ability to comply with the demonstration requirements. The review evaluated plans’ ability to quickly and accurately process claims and enrollment information, accept and transition new beneficiaries, and provide access to all Medicare and Medicaid medically necessary services.

While the state first envisioned a target implementation date in 2013, the complexities involved in completing the tasks mentioned above (i.e., the three-way contract, the provider agreement, and plan readiness reviews) led to a delay in implementation. These tasks as well as added time for outreach and education to beneficiaries and providers, setting and risk adjusting payment rates, and building provider networks were all reasons to delay the enrollment start date. Ultimately, CMS and the state settled on a three-month (May-July) phased-in enrollment process starting with Medicare opt-in (concurrently with mandatory Medicaid managed care enrollment) and delayed Medicare passive enrollment until January 1, 2015 (see enrollment section for more details).

MyCare Ohio Financial Model

Under the Medicare-Medicaid Financial Alignment Initiative, CMS will test the effectiveness of two models: 1) a managed FFS model in which the state and CMS enter into an agreement by which the state would be eligible to benefit from savings resulting from initiatives designed to improve quality and reduce costs for both Medicare and Medicaid; and 2) a capitated model in which the state and CMS contract with health plans that receive a prospective, blended payment to provide all enrolled dual eligible beneficiaries with coordinated care. Ohio is testing the capitated model.

Rate Setting

Each MyCare plan receives three different contributions to the capitated rate for each beneficiary enrolled in the financial alignment demonstration: a payment for Medicare-funded services (Parts A and B), a payment for Medicare Part D prescriptions drugs, and a payment for Medicaid-funded services. Medicare pays the MyCare Ohio plans a monthly capitation amount for Medicare Parts A/B services –risk adjusted using Medicare Advantage MCS-HCC model and the CMS-HCC ESRD model. Medicare also pays the plans a monthly capitation amount for Medicare Part D services – risk adjusted using the Part D RxHCC model. The Medicare Parts A/B capitated rate is a blended average of the county Medicare fee-for-services rate and the Medicare Advantage rate. The Medicare prescription drug capitation rate is the national average rate.

“We pushed with the plans to make sure all the incentives were there to help these people stay living independently.”

– State Official

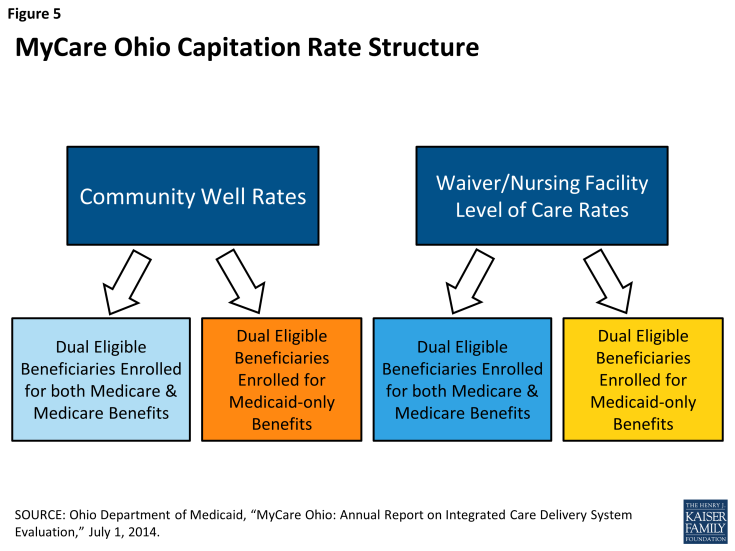

To address potential variations in risk among the participating health plans, the state uses a Member Enrollment Mix Adjustment (MEMA) for the Medicaid portion of the capitation. The MEMA will provide more revenue to health plans that have a greater proportion of high risk/cost beneficiaries, and conversely, provide less revenue to health plans that have a lower proportion of high risk/cost beneficiaries. The MEMA was incorporated into the rates starting in the fourth month of MyCare enrollment for each region and updates are made in January and July of each year. According to the three-way contract, the use of the MEMA factor is subject to change and may be a temporary feature.9In setting the Medicaid capitation rate, the state took into account the potential risk variation of various subpopulations, financial incentives, and ease of operationalization when it determined the plans’ rate structure. Specifically, these considerations included the plans’ enrollment rules, the varying levels of beneficiaries’ need, the existing Medicaid waivers, and the alignment of incentives to promote HCBS as an alternative to nursing facility placement. These incentives include paying slightly lower rates for NF services than for community-based services, to help keep people in the community. The Medicaid rates differ according to LOC and by age and geographic region. Each individual enrolled in MyCare Ohio is assigned to a specific rating category: Community Well or Nursing Facility LOC. The Community Well category represents beneficiaries who do not require a nursing home LOC. Within the community well category, capitation rates vary by the following age groups: 18-44, 45-64 and 65+. The nursing facility LOC category includes those enrolled in a HCBS waiver and nursing facility residents. For the nursing facility LOC category, there is a single rating category for each geographic region. The MyCare capitated rate structure also includes transition rules that apply to individuals who no longer meet the nursing facility LOC criteria. For individuals transitioning from nursing facility LOC to the Community Well category, the plans continue to receive the nursing facility LOC capitation rate for three months following the change in categorization. These considerations applied both to Medicaid managed care-only beneficiaries and beneficiaries enrolled in the financial alignment demonstration for both Medicare and Medicaid benefits.

Another noteworthy feature of Ohio’s financial alignment demonstration, not included in all the other states’ demonstrations, was the inclusion of a medical loss ratio (MLR) performance indicator. The MLR requires plans to spend between 85%-90% of the joint Medicare and Medicaid payment to the plans on medical care (including services and care management). If a plan has an MLR below 85%, they will be required to provide a rebate back to the Medicaid and Medicare programs on a percent of premium basis.

One of the challenges associated with MyCare Ohio was to build two unique capitation rate structures: one for dual eligible individuals who are enrolled in the demonstration for both their Medicare and Medicaid benefits and one for dual eligible beneficiaries who are enrolled in the demonstration only for their Medicaid benefits. There are also different capitation rates for people receiving home and community-based waiver or nursing facility services (mentioned above) and for individuals who do not meet an institutional LOC, resulting in a total of four different Medicaid rates (Figure 5).10 Another challenge cited by ODM officials was the fact that capitation payments in Medicaid must be actuarially sound (appropriate for populations and services covered), and therefore, deriving a methodology that met this test and accommodated the three-way contract made this effort more complex, requiring a strong working relationship between CMS and the state. Ultimately, CMS and the state settled on a rate structure where the Medicaid managed care-only capitation rates are higher than the financial alignment demonstration (both Medicare and Medicaid benefits) rates. Assumptions behind this decision included taking into account the shared savings from Medicare and Medicaid integration and assuming higher utilization of services for dual eligible individuals enrolled in managed care only for Medicaid benefits who choose to keep their own Medicare providers. A follow-up conversation with ODM officials revealed that they have not yet seen this rate setting disincentive impact plans’ efforts to enroll dual eligible beneficiaries into the fully coordinated model.

Health plans reported that it was too early to tell whether the demonstration’s financial model would be sustainable over the longer term. Each plan reported experiencing less transparency with the Medicare rate setting process than the Medicaid rate. One plan noted that the Medicare rate covered the medical portion of services but had no allowance for care management or for the administrative costs of that service. Plans reported savings targets would be difficult to achieve, especially given the 365-day care continuity requirements. When asked about identifying sources of savings in the demonstration, the plans noted two general sources: change in the population group mix (institutional, community waiver, and community well) under managed care compared to the mix in FFS, and changes in service costs for more cost-effective utilization of services. There are potential savings from serving more individuals in the community rather than institutions and providing HCBS as preventive services, before people need an institutional LOC, to avoid more costly future services. Additionally, plans noted that providing care coordination services to the community-well population could result in savings if they are able to meet these individuals in the hospital and help them to know their care managers and better manage their transition from the hospital to the community. Other potential areas for savings include: reducing emergency room visits, inpatient hospital stays, and duplication of services, and keeping people in the community rather than nursing facilities.

Built into the financial alignment demonstration are aggregate savings percentages of 1 percent in the first year of the demonstration (May 2014-December 2015), 2 percent in the second year (January-December 2016), and 4 percent in the third year (January-December 2017) (excluding the Medicare Part D component). State officials reported that savings played a fairly small role in the state’s interest in participating in the demonstration. While the long-term results may include savings, the short-term focus was on achieving better-coordinated care and better health outcomes. Several stakeholders suggested the key to reaching the savings targets would be to enroll (and maintain enrollment) of beneficiaries for both their Medicare and Medicaid benefits (and not just Medicaid benefits), although it is unclear how the timing of Medicare passive enrollment (6-8 months after Medicaid passive enrollment) will affect savings targets, especially in year one.

Quality Withhold

Included in the 3-way contract are quality withholds where CMS and the state withhold a portion of the Medicare A/B and Medicaid capitation payments – 1 percent in the first demonstration year, 2 percent in the second, and 3 percent in the third year.11 Plans can earn back these funds based on their performance on the quality withhold measures outlined in the contract. In year 1, plans are able to earn back withheld funds if they meet certain quality standards including: (1) submitting encounter data accurately and completely in compliance with contract requirements; (2) the share of beneficiaries with initial assessments completed within 90 days of enrollment, (3) establishment of a beneficiary governance board; (4) percent of best possible customer service score; (5) percent of best possible score getting appointments and care quickly; (6) share of beneficiaries with documented care goals; and (7) nursing facility diversion measure. In years 2 and 3, plan payment will be based on performance on the following quality withhold measures: (1) plan all-cause readmissions; (2) annual flu vaccine; (3) follow-up after hospitalization for mental illness; (4) screening for clinical depression and follow-up care; (5) reducing the risk of falling; (6) controlling blood pressure; (7) Part D medication adherence for oral diabetes medications; (8) nursing facility diversion measure; and (9) long term care overall balance measure.12 A unique feature of Ohio’s financial alignment demonstration, relative to other states, is the inclusion of several HCBS/rebalancing measures among the quality withholds. Specifically, these measures are: (1) Number of beneficiaries residing outside a NF as a proportion of total number of beneficiaries in plan (>100 day continuous NF stay); and (2) number of beneficiaries who lived outside a NF during current year as a proportion of beneficiaries who lived outside a NF during previous year (>100 day continuous NF stay).

Service Delivery Model

Ohio’s financial alignment demonstration was designed to better integrate Medicare and Medicaid benefits for dually eligible individuals in targeted regions of the state. Health plans are required to provide all health, behavioral and LTSS to dual eligible beneficiaries enrolled in the demonstration. As outlined in the MOU between CMS and the state of Ohio in December 2012, key objectives of the demonstration are to improve the beneficiary experience in accessing care, deliver person-centered care, promote independence in the community, improve care quality, eliminate cost shifting between Medicare and Medicaid and achieve cost savings through improvements in care coordination.

A cornerstone of Ohio’s financial alignment demonstration is the promise of comprehensive care coordination across all settings (acute, LTSS, behavioral, and social services) with the help of a care manager. With the demonstration, all beneficiaries receive care management and are assigned a care manager from their plan. The plan’s approach to care management must be person-centered, promote the beneficiary’s ability to live independently and comprehensively coordinate the full set of Medicare and Medicaid benefits. This includes helping beneficiaries transitioning from a hospital back to their home or from a nursing facility to their home. The major components of the service delivery model are described below.

Initial Assessment

Once a beneficiary is enrolled in MyCare Ohio, whether only for Medicaid managed care benefits or for both Medicare and Medicaid benefits, the plan is contractually obligated to perform an initial comprehensive assessment of the beneficiary’s medical, behavioral, LTSS and social needs. The timeframes required for completion of the initial assessment are: within 15 days of enrollment for beneficiaries assigned to the intensive risk stratification level, within 30 days for the high level, within 60 days for the medium level, and within 75 days for the low and monitoring levels.13 These timeframes were designed to ensure that those most at risk would receive the earliest assessments. Face-to-face assessments are required for beneficiaries assigned to the intensive and high-risk levels and for any beneficiary receiving home and community-based waiver services. All other beneficiaries may be assessed by telephone, unless an in-person assessment is requested. Results of the comprehensive assessment are used to confirm the beneficiary’s risk stratification level and to develop the individualized care plan (ICP). Initial ICPs must be developed within 15 calendar days of the initial assessment and include information about the beneficiary’s progress in achieving goals, coordination of care and services, use of providers, ongoing medication management, preferred method of contact, and strategy for care transitions between settings. The assessments are conducted by case managers or other licensed/credentialed professionals employed by the plans, unless the plan decides to subcontract that function out to a provider, such as the local AAAs. Provisions for conflict free case management have been built into the 3-way contract in instances where the plans directly provide or delegate waiver service coordination and case management services to beneficiaries. There are also firewalls in place for the AAAs between the areas responsible for waiver eligibility determination and waiver service coordination.

Stakeholders reported delays in initial assessments across all seven MyCare regions. Delays in initial assessments affected the transition to Medicaid managed care, and while not unique to the demonstration population, the delays were an issue that impacted the demonstration population because the same resources were being utilized among the plans. Some delay was expected given the complexity in launching a new program with over 100,000 individuals over the span of three months. Plans acknowledged the delays and the difficulty of meeting the assessment timeline requirements. Two plans noted their models seems to be working despite some delays, because of their partnership with the AAAs which allowed many MyCare Ohio beneficiaries to keep their same care manager. However, several stakeholders noted that large caseloads delegated to the AAAs were also contributing to the delays in initial assessments. Other plans had models that required beneficiaries to connect to a person different from their existing point of contact. Plans reported difficulty in contacting beneficiaries despite repeated requests to schedule an assessment. Strategies to locate individuals included phone calls, letters, relying on community health workers, visiting people’s homes, examining claims history, ER reports, and calling providers. Individuals not already connected to a waiver service or a case manager were the hardest to locate. Ultimately, there will be no quality withhold payments to the plans that do not complete the initial assessments on time.

Another reason for the delay in initial assessments could relate to a lack of beneficiary understanding and awareness of MyCare Ohio. According to some stakeholders, some individuals were denying the assessment because they were recently assessed under a previous waiver program. In other situations, beneficiaries voiced reluctance to contact a new care manager when they were happy with their previous one. A consequence of the delays in performing the initial assessment was that some individuals were not assigned a care manager until the assessment occurred (75 days or more). One stakeholder reported that beneficiaries “need access to a care manager at enrollment…someone to call for help.”

Care Coordination

Plans are required to form a care management team, called the trans-disciplinary care team, consisting of the individual, the primary care provider, specialists, the care manager, the waiver service coordinator (as appropriate), the individual’s family/caregiver/supports, and other providers based on the individual’s needs and request. The MOU outlines the role of the trans-disciplinary care team: to participate in and support care management activities, such as completion of the comprehensive assessment and development, implementation and updates to the ICP at the direction of the care manager. Prior to MyCare Ohio, only beneficiaries enrolled in an HCBS waiver or in a Medicare Advantage plan had access to a care manager, but even those individuals lacked coordination support across both the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Several months into the financial alignment demonstration, the majority of stakeholders reported that the trans-disciplinary care team was not yet functioning as designed due to delays in completing initial assessments. Looking beyond the initial months of implementation, plans acknowledged the need to ensure that care managers are engaged in service coordination. Advocates cautioned that unless the plans make a meaningful connection between care managers and individuals, outcomes of the demonstration would not be met.

“The AAAs are helping to carry out big pieces of the demonstration including assessments, care management, and care plan development. They are boots on the ground that the state and federal government doesn’t have.”

– Stakeholder

Effective January 1, 2015, an amendment to the 3-way contract allows beneficiaries who receive home and community-based waiver services to select a waiver service coordinator to facilitate and manage the delivery of waiver services authorized in the waiver service plan. A unique feature of Ohio’s financial alignment demonstration is the requirement for plans to contract with Ohio’s AAAs and other entities that have experience working with people with disabilities for waiver service coordination for individuals age 60 and over. Because of their involvement with care coordination for seniors in the Passport waiver program, the AAAs had established trusted relationships among beneficiaries and providers. The AAAs were previously providing waiver service coordination under the fee-for-service system, and therefore were equipped to provide these services at implementation. Other qualified entities may include CILs or disability-oriented case management agencies and were included in the 3-way contract language in order to give beneficiaries another option for waiver service coordination.

Stakeholders viewed the AAAs’ involvement in the financial alignment demonstration as a huge asset. Plans relied on them for their connection to community-based resources and their knowledge of services, service authorizations, and assessments. The requirement to including the AAAs in the demonstration as well as the continuity of care provisions built into the demonstration helped maintain continuity of care for seniors during the transition to managed care. One plan noted that working closely with the AAAs helped increase the opt-in percentage for Medicare services. Some advocates pushed to involve the AAAs in wavier service coordination for the under sixty population, but ultimately that flexibility was given to the plans to decide. Plans may contract with AAAs, or other entities, or provide waiver service coordination themselves for individuals under the age of 60. Health plans in the demonstration vary in the degree to which they delegate the roles of waiver service coordination and care management for beneficiaries under age 60. As of October 2014, two of the five health plans participating in the demonstration (Aetna and CareSource) fully delegated care management responsibilities to the AAAs for both the under and over 60 population, while the other three plans hired their own case managers to provide care management for those under age 60 and rely on the AAAs for waiver service coordination for individuals aged 60 and older. Plans using their own case managers reported large hiring activity associated with MyCare Ohio. The majority of the new hires were nurses, care managers, social workers, and community health workers. Plans rely on community health workers to provide peer support services that includes visits to beneficiary’s homes for in-home assessments and ensuring the beneficiary is linked with other social services or community resources.

Behavioral Health Services

State officials estimate that 16 percent of MyCare beneficiaries have behavioral health needs. Therefore, the inclusion of behavioral health services in the demonstration was essential in order to maximize care coordination and access to services across all care settings. As outlined in the three-way contract, plans are required to staff a behavioral health director whose responsibilities include ensuring access to behavioral health services (including mental health and substance abuse services), ensuring overall integration of behavioral health services in the beneficiary’s care plan, ensuring systematic screening for behavioral health disorders, and participating in management and program improvement activities for enhanced integration and coordination of behavioral health services.

Plans made a number of changes, mainly hiring of staff, to accommodate individuals with behavioral health needs. They reached out to community-based organizations and companies with behavioral health care management experience for training, hiring and conducting assessments. Plans reported having a specialized care team dedicated to serving MyCare beneficiaries with a mental illness diagnosis with care managers experienced in behavioral health. For example, a psychiatrist would serve on the trans-disciplinary care team for a beneficiary with behavioral health needs. Some of the plans had prior experience serving Medicaid beneficiaries with behavioral health needs. None of the plans reported difficulty recruiting behavioral health providers, but stakeholders and providers said the transition to managed care from fee-for-service necessitated a learning curve for new billing, coding and IT practices. One provider noted integrating physical and behavioral health has great potential but that potential would only be reached if the behavioral health specialist were part of the care planning and coordination efforts.

Supplemental MyCare Ohio Services

Financial alignment demonstration health plans in Ohio have the option of adding supplemental services or “value-added services” to their existing benefits package. Beneficiaries are made aware of these services through the member handbook and by their care managers. Some plans are offering MyCare beneficiaries enhanced transportation services including 60 one-way trips each calendar year (Molina), access to more frequent dental services (Aetna), and/or assistance with over-the-counter product expenses (Aetna, Buckeye, and Molina). However, these enhanced services are only available for MyCare Ohio beneficiaries enrolled for both their Medicare and Medicaid benefits. The structure of care coordination and benefits offered differs across the plans in terms of value added benefits, but all MyCare Ohio beneficiaries are given access to a 24/7 nurse advice call line, a 24/7 behavioral health crisis line, care coordination, and expanded HCBS waiver services (as noted earlier).

Continuity of Care Requirements

In order to minimize service disruption when transitioning from FFS to managed care, health plans must allow beneficiaries to maintain current providers and service levels at the time of enrollment, for a pre-determined amount of time, depending upon the type of service. Physician services are maintained for 90 days for high-risk individuals and 365 days for all other MyCare beneficiaries. Direct care waiver services such as personal care, adult day and home care attendant services, are maintained at current levels and with current providers at current Medicaid reimbursement rates for 365 days. For assisted living waiver services and nursing facility services, providers are maintained at current rates for the life of the demonstration. All other waiver services are maintained at current levels for 365 days and with existing providers at existing rates for 90 days. This includes services such as home medical equipment and adaptive and assistive devices, transportation, and community transition. Community mental health and addiction treatment center services are maintained at current levels of service with current providers for at least 365 days. There are some exceptions to the transition requirements.14

Stakeholders agreed that the transition requirements built into the demonstration were strong and helped ensure continuity of care during the move to managed care. Early on in the demonstration and after the 90-day transition period ended, beneficiaries reported problems accessing transportation and DME services. Follow-up interviews with beneficiary advocates in December 2014 revealed improvements with transportation services but continued problems with DME prior authorizations. Individuals in some instances were being denied equipment that had been a part of their lives and care plans for some time. Stakeholders expressed concerns about decreased service levels and HCBS provider network adequacy after the 365-day transition period expires. Providers expressed concern that plans would narrow their networks at the end of the transition periods and/or reduce payment rates.

Enrollment in MyCare Ohio

2-Part Enrollment Process and Beneficiary Choices

MyCare Ohio began by first implementing mandatory Medicaid managed care enrollment starting on May 1, 2014 in the Northeast Region (Cuyahoga, Medina, Lorain, Geauga and Lake counties). Mandatory enrollment was based on a computer algorithm that utilized current Medicare Advantage or D-SNP enrollment, past Medicaid managed care plan enrollment, and past claims and provider utilization history.15 As part of the Medicaid passive enrollment process, individuals were given the choice to voluntarily enroll in the same MyCare Ohio plan to receive Medicare services or remain in either traditional Medicare FFS or Medicare Advantage. The remaining six regions began enrollment on June 1 and July 1 of 2014. In September 2014, mandatory Medicaid enrollment was briefly put on hold to accommodate the Medicare open enrollment period. ODM announced that they would not be issuing additional mandatory enrollment notices to beneficiaries to avoid duplication during the Medicare open enrollment period (Oct 15, 2014 – December 7, 2014). Voluntary enrollment for Medicare benefits continued during this time. Beneficiaries who enrolled in managed care only for their Medicaid benefits had 90 days to switch plans before being locked-into a plan. Beneficiaries who enroll in the financial alignment demonstration (for both their Medicare and Medicaid benefits) have the ability to change health plans monthly, at any time during the year, with coverage beginning on the first of the following month.16

In October 2014, beneficiaries who had not voluntarily enrolled in the demonstration received a notice stating that effective January 1, 2015, their Medicare coverage will change to the same managed care plan that provides their Medicaid benefits and that their MyCare plan will also cover their prescription drugs.17 They were given the option to decline that enrollment and continue their current Medicare arrangement. For those who did not actively decline, as of January 1, 2015, their MyCare Ohio plan began providing both Medicare and Medicaid services. Individuals can opt-out of Medicare managed care enrollment by contacting Ohio’s enrollment broker or calling 1-800-MEDICARE. Additionally, individuals who previously requested to opt out may voluntarily opt in at any time for an effective date of the following month.

The flexibilities built into the model including the ability to change plans and opt-in and out every month for Medicare benefits, while important for beneficiary choice, have caused challenges for the state and the health plans. The enrollment/disenrollment flexibility contributes to population instability making it difficult to track individual changes. The process of changing plans begins with the beneficiary notifying the enrollment broker, and then the enrollment broker processes that change and sends that information to Medicare and the managed care plan. State officials noted that because of the daily nature of many LTSS, individuals who change plans need that communication to happen immediately between the individual, the enrollment broker, Medicare and the managed care plan to ensure a streamlined assessment process and continuity of services. Stakeholders called for better, more accurate flow of information between the state and the plans.

Stakeholders were split on whether the two-part process of Medicare opt-in enrollment (concurrent with mandatory Medicaid managed care enrollment) followed by passive Medicare enrollment was a benefit or a hindrance for the financial alignment demonstration. One stakeholder noted the two-step process allowed for “more time to bring up the program and work through issues as they arise.” Allowing beneficiaries six to eight months to voluntarily enroll for Medicare services before being passively enrolled enabled the state and plans to make adjustments to beneficiary notifications, learn from the initial rollout experience, and conduct additional outreach to beneficiaries and providers. Also, issues around the timing of Medicare open enrollment led to the decision to wait until January for Medicare passive enrollment, although letters sent out to beneficiaries arrived at the same time that regular Medicare Advantage open enrollment began in October which may have been confusing for beneficiaries. Others questioned the delay of Medicare passive enrollment since managed care plans had experience with acute services (covered by Medicare) and less experience with managing LTSS (covered by Medicaid). It is too early to know whether health plans were able to leverage opportunities to market the benefits of the demonstration to providers and beneficiaries during the months leading up to Medicare passive enrollment or whether the bifurcated enrollment process led to more confusion for dual eligible beneficiaries.

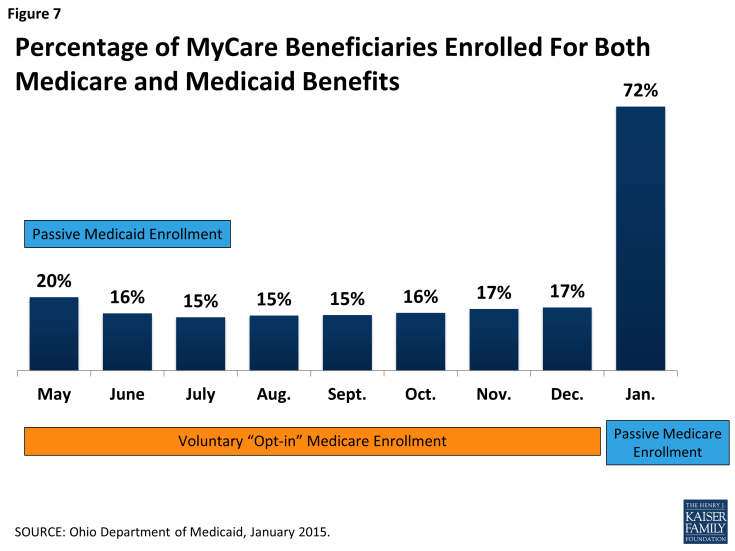

MyCare Ohio Enrollment Activity

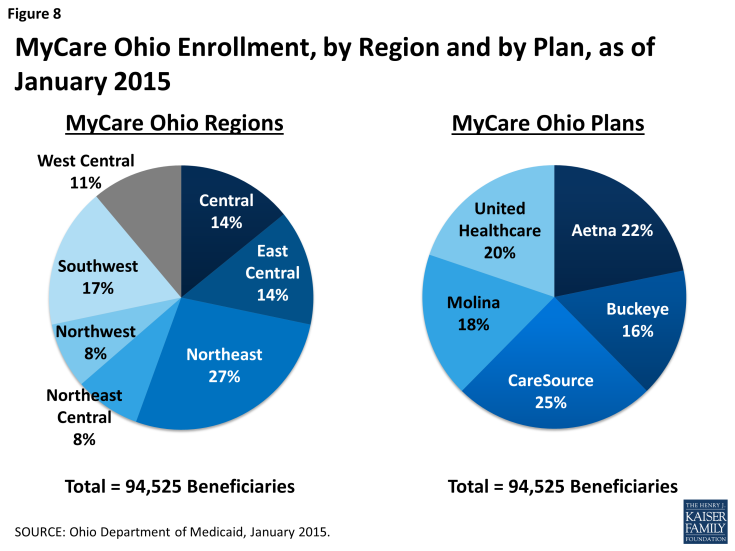

As of January 2015, a total of 94,525 individuals were enrolled in MyCare Ohio (Figure 6). Seventy-two percent (or 67,993 individuals) were enrolled in the fully integrated model for both Medicare and Medicaid services, and 28 percent (26,532 individuals) were enrolled in a plan for only for Medicaid services and chose to keep their prior Medicare Advantage plan or remain in Medicare FFS. Individuals were assigned a MyCare Ohio plan for mandatory Medicaid managed care services between May-July 2014. Over the next 8 months, the opt-in rate for Medicare services averaged around 16 percent of the eligible population until passive enrollment for Medicare services occurred and the enrollment rate for Medicare services jumped to 72 percent (Figure 7). Stakeholders were anticipating a large increase in the percentage of beneficiaries enrolled for both Medicare and Medicaid services, following passive Medicare enrollment. Looking ahead, it will be important to follow whether the health plans can maintain that level of Medicare and Medicaid participation or whether opt-out rates will increase. In Massachusetts and Virginia, for example, opt-out rates have averaged about 35% and 29% respectively.18

The Northeast region had the highest percentage of beneficiaries eligible for the financial alignment demonstration enrolled (27% or 25,794 individuals) followed by the Southwest region (17% or 16,115 individuals) (Figure 8). These regions cover the Cleveland and Cincinnati areas. With at least two health plans operating in each of the seven regions, one-quarter of demonstration enrollees were members of CareSource. CareSource is also the largest Medicaid managed care plan in the state covering over half of all Medicaid managed care beneficiaries.19 As noted earlier, CareSource has partnered with Humana in this demonstration, and Humana is the largest Medicare Advantage organization in Ohio offering plans that cover 28 percent of all Medicare Advantage enrollees.20 The Northwest region had the highest percentage of beneficiaries participating in the demonstration (for both their Medicare and Medicaid benefits) (76%), and UnitedHealthcare had the highest percentage of beneficiaries participating in the demonstration (for both their Medicare and Medicaid benefits) among the five health plans. Just prior to passive Medicare enrollment, CareSource had nearly thirty percent of its MyCare population enrolled for both Medicare and Medicaid benefits while the other plans’ Medicare opt-in rates averaged just 13 percent.

State officials and plan stakeholders reportedly pursued a mandatory enrollment process for Medicaid services in order to provide stability to the beneficiary, the provider and the managed care plan. Most of the Medicaid population in Ohio was already enrolled in managed care and they believed that this population new to managed care, the dual eligible beneficiaries, would benefit from access to care management services and better care coordination to promote improved health outcomes.

Stakeholders identified some systems issues that caused confusion during the few six months of MyCare enrollment. First, the lists of people to contact and assess were often inaccurate. This problem arose early on and continued through the months leading up to Medicare passive enrollment, although stakeholders reported fewer problems over time. In some cases, people were showing up on two lists (as members of both plans in the region) or not on a list at all. The transmittal of information between the state/CMS, the plans, and the AAAs was delayed or inaccurate, which led to service disruptions for beneficiaries. One stakeholder noted that each plan has its own IT system and never tested it to the level or magnitude of the number of beneficiaries that were being enrolled in MyCare Ohio. Another example of IT systems challenges is the lag time in processing beneficiary plan changes. Some respondents suggested MyCare Ohio beneficiaries who switch plans are going without needed services for one month or more, because the plans are unaware of the enrollment change when it is made. A more prompt notice should be used to notify past and current plans of enrollment changes so that the beneficiary does not experience any gaps in services. The reconciling of lists is also important for providers so that they know which plans to bill and can get paid on a timely basis.

Consumer advocates also reported a number of problems during the first six months of implementation related to mandatory Medicaid managed care enrollment including insufficient outreach to beneficiaries and providers; multiple, complicated written mailings; and lack of knowledge about who to call for help. One stakeholder remarked that the impact of Medicare passive enrollment would not be seen until beneficiaries begin to navigate the new system by filling a prescription or seeking services. It is possible that many of the nearly 52,000 beneficiaries who were passively enrolled in a plan for their Medicare services between December and January were not aware of a change given the challenges in locating individuals following mandatory Medicaid managed care enrollment and given the health and cognitive vulnerability of the dual eligible population.

Public Awareness and Marketing of MyCare

“People have been given an onslaught of information and change at once.”

– Stakeholder

Ohio sent letters to eligible individuals in December 2013, introducing the MyCare Ohio program and explaining how managed care affects them. Leading up to the launch, ODM and the Department of Aging sponsored regional forums, webinars and conference calls to inform beneficiaries and providers about MyCare Ohio. Outreach was funded by the state and primarily conducted by community organizations with direct access to beneficiaries such as the AAAs, CILs, and Easter Seals. The consumer enrollment process began with a Medicaid managed care mandatory enrollment notice sent initially on a rolling basis on March 1st, April 1st, and May 1st, 2014, depending on region. A reminder notice was sent to individuals who did not make a voluntary choice 30 days prior to the Medicaid passive enrollment effective date. Several stakeholders reported the 6-page written notices to beneficiaries were confusing and complicated. Individuals had opportunities to choose their plan over the phone from an enrollment broker, during regional/enrollment forums, and through face-to-face individual enrollment counseling. The Medicaid consumer hotline and website served as the primary educational and enrollment mechanisms,21 although auto-assignment was the predominant mechanism for enrollment. State SHIP programs also reported an uptick of calls related to enrollment in Medicaid managed care. Just prior to May 1st, managed care plans took over the marketing responsibility and continued training and education forums throughout the summer.22 Marketing and member materials had to be prior approved by ODM before being shared with eligible MyCare beneficiaries.

“People have gone through one crisis of disruption and now we are going to go through it all over again…with Medicare enrollment in January.”

– Provider

The majority of stakeholders agreed that beneficiaries could have been better informed that MyCare Ohio was coming. Given the physical and cognitive limitations many dual eligible beneficiaries face, any transition into a new program would likely cause confusion. Consumer advocates reported hundreds of calls from confused beneficiaries whose services had been disrupted and did not know where to turn for help. Some stakeholders suggested the enrollment of over 100,000 dually eligible beneficiaries into Medicaid managed care over the course of three-months was an aggressive timeline, leaving little opportunity to learn from initial enrollment experience in a region. Thus, “early problems happened in large numbers.” One early challenge repeatedly mentioned was difficulty with finding people. Those hardest to find were in the community well category. These individuals were not already connected to a waiver service that made locating them a difficult task. ODM officials stressed the importance of thinking about how to find people ahead of implementation and noted the value of contracting with the AAAs because of their built in contact with beneficiaries. Plans reported devoting considerable resources toward addressing initial disruptions in service with infrastructure and process improvements. Hiring and training of staff and collaborating with organizations that serve dually eligible beneficiaries to help with outreach were strategies they employed to address initial transition problems. Consumer advocates recommended broadening the state’s beneficiary assistance capacity by expanding the ombudsman program’s hours and increasing funding for local ADRNs. Other suggestions included developing an Early Indicator System, similar to the one in Massachusetts to track patterns of systemic problems.

Given early outreach challenges and potential beneficiary confusion with Medicare passive enrollment occurring at the same time as open enrollment for Part D, Medicare Advantage and the health insurance Marketplace, state officials and plans took additional steps to educate beneficiaries leading up to January 2015. These steps included simplifying the language included in beneficiary mailings, in-person meetings between the plans and community-based beneficiaries, and making sure that call centers were equipped to handle questions. Beneficiaries received a 60-day passive enrollment notice with instructions on how to actively opt-out of the financial alignment demonstration for Medicare services. Thirty days before the passive enrollment effective date, January 1, 2015, beneficiaries received another reminder notice with the effective enrollment date and the name of the assigned MyCare Ohio plan. By the time Medicare passive enrollment occurred, beneficiaries should have received an initial assessment and been given a care manager to help them access care through the plan. The promise of a ‘single point of contact’ or a care manager will hopefully help to mitigate disruptions in continuity of care caused by the transition to managed care.

Provider Involvement

In the 3-way contract, plans must demonstrate annually, as required by CMS and ODM, an adequate provider network sufficient in number, mix, and geographic distribution, to ensure adequate access to medical, behavioral health, pharmacy, and LTSS providers. Each plan reported starting with their existing networks to form a provider network for MyCare Ohio beneficiaries. They engaged with networks from existing Medicaid and Medicare Advantage (or SNPs) contracted providers that included physician, hospital, and pharmacy provider groups, and relied on historical FFS files to identify new network HCBS providers. The 3-way contract also included specific access standards related to LTSS providers including providing: at least two community LTSS providers in each region for services such as enhanced community living, waiver transportation, home medical equipment and supplemental adaptive and assistive devices; at least two community LTSS agency providers for personal care and waiver nursing services; and at least one community LTSS provider in each region for home delivered meals and home modifications maintenance and repairs.23

Each plan and its network providers must comply with the ADA and maintain capacity to deliver services in a manner that accommodates the needs of MyCare Ohio beneficiaries, including physical, geographic and communication needs. All health plans are required to have written policies and procedures in place to assure ADA compliance and must designate to ODM an individual who is responsible for ADA compliance. Some of the policies designed to ensure access include flexibility in scheduling, providing interpreters or translators, and individualized assistance. Plans are also required to conduct annual education programs for their trans-disciplinary care team providers related to ADA/Olmstead requirements, person-centered care planning processes, and accessibility and accommodations. Some stakeholders expressed concern about plans’ ability to meet ADA obligations. This will be an important issue to follow as the demonstration moves ahead.

“Providers have a significant impact on the decision consumers are making regarding enrollment…plans knew this would be the case and they are worried.”

– Beneficiary advocate

Both state officials and plans put forth tremendous effort to educate providers about MyCare Ohio, yet some provider groups were slow to engage and stakeholders felt more targeted outreach would have helped. Not understanding the program or fear of reductions in payment rates were reasons that some providers reportedly chose not to participate in MyCare. State officials reported engaging with providers and beneficiaries for many months leading up to the launch and on an ongoing basis. They facilitated forums, meetings, and made information available online for providers, advocates and associations. After May 1, 2014, plans continued training and educational forums through the summer. Plans reported that delaying the rates made it hard to engage with providers. State and CMS officials reportedly took time to negotiate which Medicare and Medicaid factors and growth rates to consider when determining the rates. Outreach to LTSS providers required more time and resources compared to other provider groups since this cohort was new to managed care billing and reimbursement practices. One plan reported conducting over one hundred training sessions for HCBS providers. Stakeholders suggested both the plans and the state could have done a better job with basic program education that informed the provider “what the program is doing and what it is not doing.” The issues involving providers were related to the concurrent implementation of mandatory Medicaid managed care but also affected the capitated financial alignment demonstration, which encompasses both Medicare and Medicaid services.

Independent Providers

One of the most widely cited challenges initially for MyCare Ohio involved independent providers (IPs). Ohio has an estimated 12,000 IPs who are home health workers that provide assistance with activities of daily living, including dressing, bathing, feeding, and toileting. Just prior to the MyCare rollout, a third-party billing agent for IPs dropped the service with little notice, requiring the IPs to submit claims directly to the managed care plans in order to get paid. Claims submission was a skill with which few IPs had any experience prior to MyCare. As a result, many IPs were not paid on a timely basis due to failure to submit accurate claims and added processing time to transition the IPs into the new system. Meanwhile, managed care plans were used to reimbursing claims filed on a 30-day cycle, but IPs were used to being paid faster, so even some “clean claim” payments were delayed. “Nobody was paying attention to MyCare until they stopped getting paid,” reported one LTSS provider. Stakeholders claimed that some IPs walked off the job because of failure to be paid, which jeopardized the health and safety of some MyCare beneficiaries. It also exposed a large educational gap among providers, forcing the plans to reach out to IPs and educate them on the process of submitting claims correctly. Unlike other provider groups, IPs are difficult to reach because they lack an association to voice their needs collectively or to educate them on systems changes.

“We weren’t reimbursing IPs for services rendered, we were giving them a paycheck.”

– MyCare Ohio plan

Once the billing problem was exposed, plans set up weeknight and weekend trainings, often on a one-on-one basis, to engage providers and teach them how to bill through an online portal. Each plan now has an online portal where providers can submit claims on their own. Other provider groups reported experiencing payment delays during the transition to managed care, but generally they were larger entities with larger cash flow to absorb the delay. Some providers were given advance checks from the plans in order to make up for delayed payments. Another plan reported speeding up the process of payments to twice a month. Stakeholders agreed that IPs should have been better informed that MyCare Ohio was coming and what impact it would have on their billing process. They also suggested that plans should have engaged beneficiaries and advocates ahead of implementation to better understand the population served by IPs and their daily needs.

Primary Care Providers

Another provider group that has been difficult to engage is primary care providers (PCPs). The 3-way contract requires plans to ensure that all beneficiaries have a network PCP of their choice upon enrollment. PCPs reportedly knew very little about the MyCare Ohio ahead of time, yet are seen as a critical component of the demonstration and influential with respect to enrollment decisions for Medicare services. In general, beneficiaries want to stay with their PCPs, so provider participation in MyCare can have a direct influence on an individual’s decision to enroll in the fully integrated model (for Medicare and Medicaid services). Other providers with influence over beneficiary decisions included pharmacy and HCBS waiver providers. Despite the potential for better-coordinated care for individuals, some PCPs were reluctant to participate, citing overlap with other demonstrations and added billing requirements as barriers. One PCP noted that starting with just mandatory Medicaid managed care enrollment (and not Medicare and Medicaid simultaneously) made some physicians reluctant to participate, given that physicians generally accept Medicare payment but not all accept Medicaid. Stakeholders reported optimism that PCP participation would improve after passive Medicare enrollment in January 2015. If it does not, however, and large numbers of beneficiaries opt-out of Medicare services, stakeholders noted it would be a ramification of not having adequately educated providers about MyCare.

PCPs can be a difficult group of providers to reach, especially the ones who are not affiliated with large health systems or groups. Provider advocates reported that provider participation in MyCare Ohio would be driven by large provider groups’ willingness to enter into contract arrangements with health plans. The demonstration was designed to promote provider participation and to minimize disruptions in care by including a transition period of up to one year for physicians who do not have a relationship with a patient’s MyCare Ohio plan. During that transition, physicians may continue to serve MyCare Ohio beneficiaries, however, they must make authorization and payment arrangements directly with the MyCare Ohio plan. Beyond the transition period, health plans may choose to continue with any certified provider, regardless of whether or not they contracted with a plan. Plans reported ongoing efforts to increase provider education and outreach.

Transportation Providers

In the early stages of MyCare Ohio, the transition to managed care disrupted established communication channels between the AAAs and transportation providers leading to disruptions in services for MyCare beneficiaries. Prior to MyCare, the AAAs were able to directly arrange transportation services between a beneficiary and a provider. Health plans are managing transportation services differently now. Some MyCare plans manage their transportation services through their own case managers while other plans have subcontracted with a third-party company to manage the transportation services of MyCare Ohio beneficiaries. As a result of the transition, beneficiaries reported examples of multiple transportation agencies arriving to pick up a beneficiary as well as “a lot of no-shows.” Stakeholders heard reports of a subcontractor company calling a taxi service instead of a transportation provider to transport individuals with physical disabilities. Although some transportation providers use taxis for non-emergency transportation services, one stakeholder noted, “Curb to curb transport does not work for this population; our population needs door to door transportation.” Stakeholders reported a lack of understanding between the health plans and the beneficiary’s transportation needs, and a lack of understanding of responsibility for transportation services. For example, some plans’ decisions reflected their failure to understand that the scope of transportation services includes non-medical transportation to promote social interactions. Transportation providers working with subcontractor companies also reported having to record more complex billing records and hope to see a smoother and more cost effective billing system going forward. Plans were not obligated to continue existing relationships with transportation providers after the first three months of enrollment. One transportation provider expressed concern about securing a contract with the plans after the transition period ends.

Beneficiary Protections and Engagement

Enrollment and Implementation Workgroup

ODM convened a group of stakeholders consisting of advocates, the plans, providers, beneficiaries, and others to advise and provide input on MyCare communications and processes. State officials characterized the creation of the enrollment workgroup as a valuable component of the demonstration. The workgroup assisted with drafting and vetting of letters, developing instructional material, and organizing regional forums for beneficiaries and providers. Following the launch date of MyCare, the group transitioned to an implementation workgroup that continues to support the demonstration and meets every other month.

Demonstration Ombudsman

MyCare Ohio has an ombudsman program that functions separately from the health plans and the state Medicaid agency, although it is still part of state government, to help beneficiaries access covered services and to handle complaints. In February 2014, the Ohio Department of Aging applied for and received CMS funding to implement the financial alignment demonstration’s ombudsman program. CMS awarded the ombudsman program approximately $1.2 million for the three-year demonstration. Building upon the existing state long-term care ombudsman program staff of 93 ombudsmen and 300 volunteers, MyCare Ohio added one ombudsman coordinator and four regional MyCare ombudsman whose primary focus is on the demonstration. Prior to the demonstration, the state ombudsman program had experience working as an independent advocate for individuals with medical and LTSS needs in both institutional and community-based settings.24 In addition, the state ombudsman had experience working with Medicaid Money Follows the Person program participants and through that program, individuals with behavioral health issues. One ombudsman noted it was a “natural fit” that the state ombudsman offices would be involved with the demonstration because of this experience working with the ODM. In Ohio, the ombudsman’s office was involved early on with demonstration planning and participated in the enrollment (and implementation) workgroup. They engaged with the managed care plans and ODM before they started independent oversight of the demonstration and advocacy work, and participated in weekly meetings with the plans and ODM. During the initial months of implementation, the demonstration ombudsman reported focusing on integrating the estimated 60,000 community well population into the current ombudsman services, responding to beneficiary complaints, and securing additional funding so that each of the seven MyCare Ohio regions would have a local ombudsman.

“States that implement this model need to be aware that they are going to create a series of problems for the beneficiaries. They need to be clear with them that there is going to be a period of transition and there needs to be an easy way that they can seek help. Right now, it’s not clear whether the Medicaid office or the plans or the OSHIP or ombudsman is responsible.”

– Stakeholder

State officials characterized the ombudsman program as a valuable resource during the first months of the demonstration highlighting its transparent relationship with the state and the plans. However, some stakeholders questioned the effectiveness of the program due to the low number of complaints reported compared to what other advocacy groups were experiencing. In Ohio, the Ohio Senior Health Insurance Information Program (OSHIP), the plans, the ADRNs, the Ohio Consumer Voice for Integrated Care (OCVIC), legal aid agencies, and the ombudsman all serve as points of contact for beneficiary problems or complaints. No single entity is responsible for logging and reporting those beneficiary issues leading to uncertainty about the number and severity of problems and complaints. One key informant suggested Ohio develop an Early Indicator System modeled after the one in Massachusetts. In the meantime, the state and plans have tried to raise awareness about the ombudsman program and the resources it offers, including for example, representation in appeals and explaining to beneficiaries their options for switching plans. Plans were required to tell beneficiaries about the ombudsman program in the member handbook, and they increased awareness by including ombudsman phone numbers on letters to beneficiaries. The local aging and disability resource networks (ADRNs) have also done outreach for the ombudsman program.

Consumer Advisory Council

All plans are required to have a Consumer Advisory Councils (CAC) in each region the plan serves. Each CAC must be made up of at least 20 percent beneficiary representatives and reflect the diversity of the MyCare population. Organizations such as Linking Employment, Abilities and Potential (LEAP), a federally recognized Center for Independent Living, are engaging with the plans to help train consumers to participate in the councils so that plans can better understand how to contact and communicate more effectively with beneficiaries. Each CAC must meet quarterly and gives direct feedback about the policies and protocols adopted by the health plan. Stakeholders called for more frequent meetings, especially early on in the demonstration to address issues that arise. The establishment of these CACs are one of the “quality withhold” measures discussed previously.

Additionally, the Universal Health Care Action Network of Ohio (UHCAN), an independent community-based organization, received a grant through Community Catalyst to create a coalition to support MyCare Ohio beneficiaries. The Ohio Consumer Voice for Integrated Care (OCVIC) consists of a statewide coalition of aging and disability advocates that seek to organize and educate MyCare Ohio beneficiaries. OCVIC has been heavily involved during the MyCare rollout building a voice for MyCare beneficiaries and advocating for policy changes going forward.

Grievances and Appeals

Financial alignment demonstration beneficiaries who are dissatisfied with their plan’s decisions about service authorizations can file appeals with the plan, and are entitled to use all of the appeals processes applicable to Medicare and Medicaid. Demonstration beneficiaries learn about the right to appeal from the state, the ombudsman and the plans. Ombudsman received training in the appeals process and can represent beneficiaries in appeals (although they are not uniquely assigned to do so), and the state sent notices to beneficiaries with information about the right to appeal. Each service denial/termination notice from a plan also explains this information. Like other states’ demonstrations with the exception of New York, the Ohio appeals systems are not truly integrated. However, Ohio’s financial alignment demonstration is providing aid pending appeal (continued services) for both Medicare and Medicaid benefits (excluding Part D) during internal plan appeals. This is a significant feature of the demonstration and not a feature of regular Medicare. Also, aid pending appeal is not subject to recoupment if the beneficiary’s appeal is ultimately unsuccessful, another feature that is not typical to most state Medicaid programs.

It is too early to determine whether beneficiaries are experiencing challenges related to navigating the demonstration’s appeals process. The ombudsman office and stakeholders expected to see more beneficiaries utilizing the appeals process following passive Medicare enrollment in January 2015. Looking ahead, it will be important to monitor the impact of the ombudsman programs and its ability to assist beneficiaries with grievances and appeals, especially once the care continuity protections during the transition to managed care expire.

Performance Measurement and Achieving Outcomes

Quality Metrics and Reporting

There are a significant number of quality measures contained in the financial alignment demonstration. These eighty-two metrics relate to access and quality of services (including behavioral health and LTSS), care coordination/transitions, health and well-being, beneficiary experience, screening and prevention, and quality of life. The vast majority of quality metrics in the contract are core measures required by CMS, while the rest are state-specific. They include reporting of all National Committee for Quality Assurance/Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (NCQA/HEDIS), Health Outcomes Survey (HOS), and Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) measures and all existing Part D metrics. The state-specific measures relate to nursing facility residents, nursing facility diversion, long-term care rebalancing and long-term care transitioning. Some of the measures are specified quality withhold measures, as discussed in a previous section. There are other non-quality withhold measures related to LTSS and they include: 1) Percent of all long-stay NF residents whose late-loss ADL needs increase compared to prior assessment (bed mobility, transferring, eating, toileting); 2) Number of beneficiaries discharged from NF to community who do not return to NF during current year as proportion of number of beneficiaries in NF in previous year; and 3) Number of beneficiaries in NF during current or previous year who were discharged to community for at least 9 months during current year as a proportion of number of beneficiaries in NF during current or previous year (100+ days) . CMS and Ohio will continue to work jointly to refine and update these quality measures in years 2 and 3 of the demonstration.

State officials reported focusing on process issues (getting people enrolled, completing assessments, paying providers, etc.) during the first six months of the demonstration and expect to be “working heavily on the quality metrics in the near future” that are more focused on outcomes. From the plans’ perspective, there was concern about the ability to attain quality outcomes with beneficiaries churning on and off a plan on a monthly basis. Another concern related to the low Medicare opt-in rate for the financial alignment demonstration leading up to passive Medicare enrollment. Both these concerns potentially hinder plans’ ability to maximize comprehensive care coordination and meet quality targets. Stakeholders acknowledged the comprehensive quality metrics included in the demonstration but expressed concern that evaluations will be directed toward HEDIS measures rather than consumer satisfaction and the ability to keep people at home and not in nursing facilities.

Outcomes and Evaluation