COVID-19 Vaccine Access for People with Disabilities

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a heavy toll on people in nursing homes, with those in long-term care facilities accounting for a disproportionate share of all deaths attributable to COVID-19 to date. However, less attention has been paid to nonelderly people with disabilities who use long-term services and supports (LTSS) but live outside of nursing homes. This population includes people with a range of disabilities, such as people with autism or Down’s syndrome who live in group homes, people with physical disabilities who receive personal care services at home, and people who are receiving behavioral health treatment in residential facilities. Some nonelderly people with disabilities receive LTSS in a variety of community-based settings such as group homes, adult day health programs, and/or their own homes. Other nonelderly people with disabilities receive LTSS in institutional settings such as intermediate care facilities for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities (ICF/IDDs) or behavioral health treatment centers for people with mental illness or substance use disorder. Many nonelderly people with disabilities, both in the community and in institutions, rely on Medicaid as the primary payer for the LTSS on which they depend for meeting daily self-care needs.

Nonelderly people with disabilities and the direct care workers who provide their LTSS have similar risk factors for serious illness or death from COVID-19 compared to their counterparts in nursing homes, due to the close contact required to provide assistance with daily personal care tasks, such as eating, dressing, and bathing; the congregate nature of many of these settings; and the highly transmissible nature of the coronavirus. Seniors in nursing homes are explicitly included in the top priority group in all states’ COVID-19 vaccine distribution plans, but nonelderly people with disabilities who use LTSS may be not prioritized. This issue brief presents current state-level data about COVID-19 cases and deaths in settings that primarily serve nonelderly people with disabilities and summarizes available research on this population’s elevated risk of severe illness and death; explains how nonelderly people with disabilities and their LTSS providers are reflected in state vaccine prioritization plans; and discusses key issues related to vaccine access for these populations.

What is known about COVID-19 among people with disabilities?

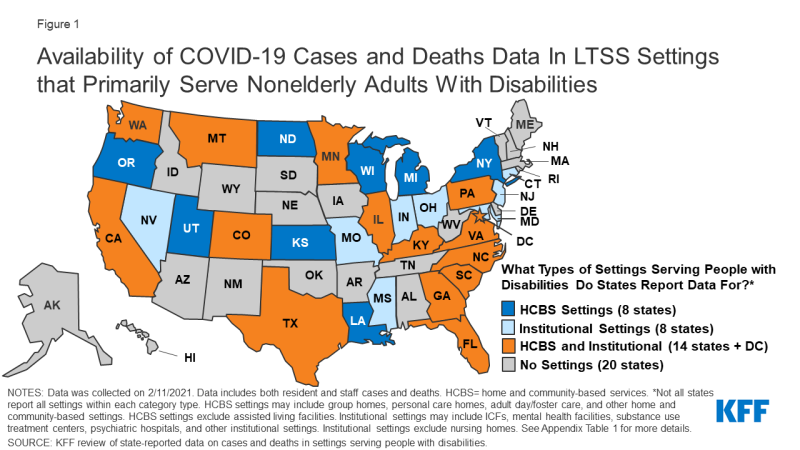

As of February 11, 2021, 31 states report at least some data on COVID-19 cases and deaths in LTSS settings that primarily serve nonelderly people with disabilities (Figure 1 and Appendix Table 1). These settings include both home and community-based settings such as group homes, personal care homes, adult day programs, and other community-based settings; and institutional settings such as intermediate care facilities and psychiatric institutions. Not all states report all types of settings within each category. These data exclude settings that primarily serve elderly adults, such as nursing facilities and assisted living facilities (ALFs), to best reflect cases and deaths solely among nonelderly adults with disabilities. For state-level data broken out by resident/staff cases/deaths, details on the types of facilities included in each state’s count, dates of data, links to the state reports, and additional notes, see Appendix Table 1.

Figure 1: Availability of COVID-19 Cases and Deaths Data In LTSS Settings that Primarily Serve Nonelderly Adults With Disabilities

The wide variety in state reporting makes it difficult to compare between states or have a complete understanding of how people with disabilities have been impacted by the pandemic. Among states reporting data, there were 111,000 cases and over 6,500 deaths across these settings as of February 11, 2021 (Figure 1). Of the 31 states reporting data, 8 states report data only for institutional settings, 8 states report data only for home and community-based settings, and 15 states report data for both settings. Thirty-one states report cases and 25 states report deaths. States also vary in whether they report only data on residents and staff separately or combined (Appendix Table 1). State reporting also varies in other ways, such as inclusion of only active cases (e.g., MA, UT), inclusion of data within broader long-term care reporting (e.g., ID, MD, MS, OK, GA, KY, LA, NC, ND), and level of detail in facility-level information. Additionally, states use different definitions or categorizations for the same types of facilities, making cross-state comparison challenging.

Data from a limited number of states suggest that LTSS residents in institutions other than nursing and assisted living facilities, as well as those in some community-based settings, face an elevated risk of COVID-19 infection (Table 1). Overall, limited data on the number of people in HCBS and institutional settings other than nursing and assisted living facilities makes calculating case or death rates difficult. However, eight states (CT, IL, NJ, OR, PA, WA, WI, TX) provide resident census data to calculate the shares of residents that have been impacted in certain settings. Among the states that provide census data on institutional settings, cumulative data show that between 19% (Connecticut’s mental health facilities) and 50% (Pennsylvania’s state centers for individuals with intellectual disabilities) of residents were infected. These rates are on par with the share of residents infected in nursing homes, which, using 2019 resident census data and resident case counts as of the end of January 2021, is about 50%. These rates are also higher than population level rates, which show more than 8% of the US population infected as of mid-February 2021. For states that provide census data on home or community-based settings, between 2% (Oregon’s Adults with Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities Foster Care HCBS waiver) and 19% (Illinois’ Community Integrated Living Arrangements group homes) of residents were infected. Given the limited sample size and wide state variation, this data should be interpreted with caution. However, this data supports other research suggesting that congregate settings, particularly larger facilities, are at high risk of having an outbreak.

| Table 1: Share of Residents Who Were Infected with Coronavirus in Selected State Settings | |||

| Residents Coronavirus Cases | Resident Census | Share of Residents Infected With Coronavirus | |

| Home and Community-Based Settings | |||

| Illinois Community Integrated Living Arrangements | 1,859 | 9,992 | 19% |

| Oregon ODDS Services – Adult DD Foster Care | 66 | 2,928 | 2% |

| Oregon ODDS Services – Adult DD Group Homes | 155 | 3,022 | 5% |

| Washington DDA Community Residential Service Providers | 668 | 4,500 | 15% |

| Wisconsin HCBS Waiver: IRIS | 1,381 | 22,332 | 6% |

| Wisconsin HCBS Waiver: Managed Long-Term Care | 8,155 | 55,009 | 15% |

| Institutional Settings | |||

| Connecticut DMHAS Facilities | 142 | 760 | 19% |

| New Jersey State Psychiatric Facilities | 332 | 1,151 | 29% |

| Pennsylvania State Centers | 321 | 640 | 50% |

| Pennsylvania State Hospitals | 560 | 1,348 | 42% |

| Texas State Supported Living Centers | 1,302 | 2,777 | 47% |

| Texas State Hospitals | 715 | 1,678 | 43% |

|

NOTES: Data are “as of” various dates; data was collected on 2/11/2021. These settings were selected based on states that specified a resident census count upon which certain case counts were based. Resident census counts in each setting reflect multiple facilities/residences. See Appendix Table 1 for links to state reports.

SOURCE: KFF analysis of state-reported data on cases and deaths in settings serving people with disabilities.

|

|||

Other research shows that nonelderly people with disabilities who receive LTSS in settings other than nursing homes face similar COVID-19 risk factors compared to people in nursing homes. Like those in nursing homes, people with disabilities rely on the close physical proximity of caregivers for communication and daily needs, which limits their ability to adopt preventive measures such as social distancing. An October 2020 study found that people with I/DD living in group homes in New York are at greater risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19 compared to the general population. Another study from July 2020 found greater risk for contracting COVID-19 among people with I/DD, and a greater case fatality rate for nonelderly adults with I/DD, compared to those without I/DD. A November 2020 analysis of private insurance claims found that people with “developmental disorders” (such as speech/language, scholastic skills, and central auditory processing disorders) had the highest odds of dying from COVID-19 and those with intellectual disabilities (such as Down’s syndrome) had the third highest risk of death from COVID-19.

Research also suggests that people with disabilities who are members of racial or ethnic minority groups are disparately affected by COVID-19. A January 2021 study found that counties with higher rates of COVID-19 were home to disproportionately higher shares of people with I/DD who are Black, Asian, Hispanic or Native American; below poverty; young; and female. A January 2021 House Ways & Means Committee Majority Staff report noted that Black working people with disabilities are more likely to have experienced job loss during pandemic, compared to other racial or ethnic groups.

In addition to increased risk from COVID-19, people with disabilities who rely on LTSS to meet daily needs also risk experiencing adverse health outcomes due to interruptions in care caused by the pandemic. An HHS report on direct service providers found that workforce shortages have been exacerbated during the pandemic, increasing the risk of adverse health outcomes among people with disabilities due to lack of care. A MACPAC report on people with I/DD noted that some people with disabilities have suspended in-home services during the pandemic and some workers have declined to enter client homes due to health and safety concerns, including challenges with accessing personal protective equipment. People with disabilities also have faced discriminatory access to care and care rationing based on disability during the pandemic, which has been the subject of HHS Office for Civil Rights guidance and several case settlements.

Direct care workers who provide LTSS to people with disabilities outside of nursing homes also face increased risks from COVID-19, similar to their nursing home counterparts. For example, a House Oversight Committee survey in August 2020 found that behavioral health treatment facility staff are more likely to have contracted COVID-19 compared to the general population. In addition, 24% of family caregivers for people with I/DD are over age 60 and therefore at higher risk of complications and death themselves from COVID-19.

How are people with disabilities reflected in state vaccine prioritization plans?

State vaccine prioritization plans explicitly include people in nursing homes and seniors in general, consistent with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendations. In December 2020, ACIP recommended that health care personnel and long-term care facility residents be placed in the top priority group (Phase 1a) for COVID-19 vaccine distribution. The ACIP recommendations define long-term care facilities as nursing homes, skilled nursing facilities, and assisted living facilities. Other ACIP guidance notes that states may choose to include people who reside in congregate living facilities, such as group homes, in the same priority group as frontline facility staff, due to “their shared increased risk of disease.” States have discretion about which groups to prioritize in their vaccine distribution plans. State vaccination plans and priority groups are continuing to evolve in response to changes in federal guidance as well as other considerations such as vaccine availability. State plans also vary widely in their comprehensiveness and transparency, with some offering more detail on priority populations than others.

Few state vaccination plans explicitly mention people with disabilities (other than people with “high risk medical conditions”). Prioritizing certain high risk medical conditions may include some but not all people with disabilities. In addition, the high risk medical conditions group does not always include or account for the increased risk to nonelderly people with disabilities who receive direct care services and/or live in congregate settings outside nursing homes. A few states do specifically prioritize people with disabilities in their vaccination plans. For example, Tennessee includes people ages 18-74 who are unable to live independently and Oregon includes people with disabilities who receive services in their homes in Phase 1a, the same priority level as people in nursing homes. Maryland and Ohio include people with developmental disabilities in Phase 1b, Illinois includes people with disabilities in Phase 1b, and Nevada and Washington include people with disabilities in Phase 1c (limited to those with disabilities that prevent their adopting of protective measures in Washington). California recently clarified that as of March 15, 2021, health care providers can use their clinical judgment to prioritize people with a developmental or “other severe high-risk disability” who, if infected with COVID-19, are likely to develop severe life-threatening illness or death, will have limited ability to receive ongoing care or services vital to well-being and survival, or will face challenges in adequate and timely COVID-19 care due to their disability.

While all state vaccination plans include people in nursing homes in Phase 1a, and most include ALFs, few mention other LTSS settings, and those that do typically do not place other LTSS settings at the same priority level as nursing homes. Three states (DC, NJ, OH) include psychiatric hospitals in Phase 1a. Nine states include group homes in Phase 1b (AK, AL, DC, MD, NM, ND, SD, WA) or 1c (DE for those with high risk conditions). Two states (WI, WY) include people receiving services under certain Medicaid HCBS waivers in Phase 1b. A few states include other LTSS settings in Phase 1b: behavioral health treatment centers (IA, ND, NM), ICF/IDDs (DC, NH), and people receiving LTSS at home (IA, PA). Other state plans generally mention congregate settings (in Phase 1b or 1c) without further details so it is unclear whether LTSS settings are included.

Few state vaccination plans explicitly mention direct care workers who provide LTSS in settings other than nursing homes. Staff at congregate settings typically are included in the same phase or earlier than residents. Some states specify staff in different LTSS settings in Phase 1a, but it is not always clear from state plans that all LTSS workers are included in the “health care workers” category. For example, some family caregivers and others who provide self-directed HCBS are recognized as Medicaid HCBS providers for purposes of reimbursement but may not work through a provider agency or be recognized as having the same licensing as providers in LTSS facilities.

What other policy issues will affect access to vaccines for people with disabilities?

People with disabilities who receive services in the community or in non-nursing facility institutions may face accessibility barriers at vaccine distribution sites. In many cases, people with disabilities will need to travel to a distribution site to receive their vaccines. For example, to date, the federal government’s Long-Term Care Pharmacy Partnership program has been limited to facilities where the majority of residents are age 65 or older, and has not included congregate settings that primarily serve nonelderly people with disabilities, such as those with I/DD or behavioral health needs. The Biden Administration’s National Strategy for COVID-19 Response and Pandemic Preparedness supports expanding this program to other congregate settings, including those that serve people with I/DD. The accessibility of community-based vaccine distribution sites also could affect the ability of people with disabilities to receive vaccines. These considerations include factors such as whether sites are physically accessible for people with mobility impairments and whether reliable public or other transportation is available to get people to the site. Vaccine distribution efforts could consider partnering with state Medicaid agencies to leverage Medicaid’s non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) benefit. Medicaid benefit provides transportation to and from healthcare providers and could be used to facilitate access to community-based vaccine distribution sites for enrollees, including those with disabilities. Transportation to receive vaccines may be especially important due to the temperature and storage requirements that may create challenges for administering the currently approved vaccines in people’s homes.

People with disabilities and their direct care providers may benefit from focused messaging as part of general vaccine outreach and public education efforts. Outreach efforts targeted to people with disabilities could be part of broader public education strategies related to vaccine distribution. Making information available in plain language and in accessible formats (such as for people with vision, hearing, or cognitive disabilities) can help ensure that it is useful to people with disabilities. Accessible information about where and when to access the vaccine will be important, especially as state prioritization plans continue to evolve, and many people with disabilities are eager to receive the vaccine given their increased risk. Public outreach campaigns also may consider how to address concerns about the COVID-19 vaccine that stem from health care discrimination experienced by people with disabilities by offering opportunities for two-way dialogue to discuss questions and concerns and build trust. Historically, many people with disabilities have experienced discrimination by being segregated in institutions and subject to involuntary sterilization. People with disabilities continue to experience barriers to needed healthcare services, due to inaccessible buildings or medical equipment (such as examination tables, radiology machines, and scales) or ineffective communication (such as lack of sign language interpreters during medical appointments). In addition, during the COVID-19 pandemic, policies to ration access to treatment, such as ventilators, have been successfully challenged as discriminating against people with disabilities. Public health departments and others involved in outreach efforts could partner with state Medicaid agencies to reach vulnerable populations, such as people with disabilities and their health care providers. Many people with disabilities receive Medicaid, and state Medicaid programs already may have established relationships with community-based health care and LTSS providers who may be trusted sources of information for enrollees.

Finally, policymakers may want to consider people with disabilities in data collection efforts to help inform and refine current vaccine distribution and access efforts and identify disparities such as those based on race or ethnicity. The Biden Administration’s National Strategy acknowledges that gaps in data exist and endorses improved COVID-19 data collection and public health guidance specific to high risk populations, including people with disabilities and those who are members of racial/ethnic minority groups.

Looking ahead more broadly in pandemic response efforts, provisions in the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s COVID-19 relief bill recognize the similar risks posed to residents and direct care workers in nursing homes and congregate community-based settings. The bill would provide $1.8 billion for COVID-19 testing, contact tracing, and mitigation activities in congregate settings, including shared living arrangements for people with disabilities as well as institutional settings such as long-term care facilities, psychiatric hospitals, psychiatric residential treatment facilities, intermediate care facilities, and other residential care facilities. In addition, the bill would allow states to use temporary enhanced federal matching funds for Medicaid home and community-based services to help seniors and people with disabilities in both nursing homes and congregate community settings relocate to their own homes in the community. The COVID-19 pandemic’s disproportionate impact on people who live and work in both institutional and community-based congregate settings has renewed interest among policymakers, seniors, people with disabilities, direct care workers, caregivers, and others in Medicaid’s role in providing services and supports for independent community living.