Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA): State-by-State Estimates of Reductions in Federal Medicaid Funding

Medicaid Changes under the BCRA and Possible State Responses

Our analysis examines the changes in the BCRA that would phase out the enhanced matching rate for the ACA Medicaid expansion and limit federal Medicaid spending to a capped amount per enrollee for five eligibility groups (expansion adults, other adults, children, the elderly and people with disabilities). First, under the BCRA, for states that adopted the expansion as of March 1, 2017, the enhanced federal match would phase out from 90% in 2020 to 85% in 2021, 80% in 2022, 75% in 2023 and then to the regular state match rate in 2024 and beyond. This phase out lowers federal Medicaid spending relative to current law, under which federal financing for the expansion population would remain at 90% in 2020 and in subsequent years.

Second, under the BCRA, federal Medicaid spending for most enrollees would be limited to a set amount per enrollee. To establish these limits, states would use data from FY 2014-2016 to develop base year per enrollee spending that would be inflated to 2019 based on the medical component of the consumer price index (CPI-M). Beginning in 2020, federal spending would be limited to the federal share of spending based on per enrollee amounts calculated by inflating the base year spending by CPI-M for children and adults and CPI-M plus one percentage point for the elderly and disabled. Beginning in 2025, all per enrollee limits would be increased by general inflation (CPI-U). Certain spending and populations would be excluded from the per enrollee caps, including enrollees who do not receive the full scope of Medicaid benefits.

States could respond to these changes in federal policy in several ways. We examine changes in federal Medicaid spending under two possible scenarios of state responses: (1) All states, both expansion states and non-expansion states, fill gaps in the loss of federal funding and maintain coverage, including the ACA Medicaid expansion coverage, and (2) states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA fully drop their expansions but maintain spending and coverage for other groups, resulting in declines in both federal and state spending. In the second scenario, we model the loss of federal dollars that the state would have received had it fully maintained its expansion.

Key Findings

Estimated Changes, 2020-2029

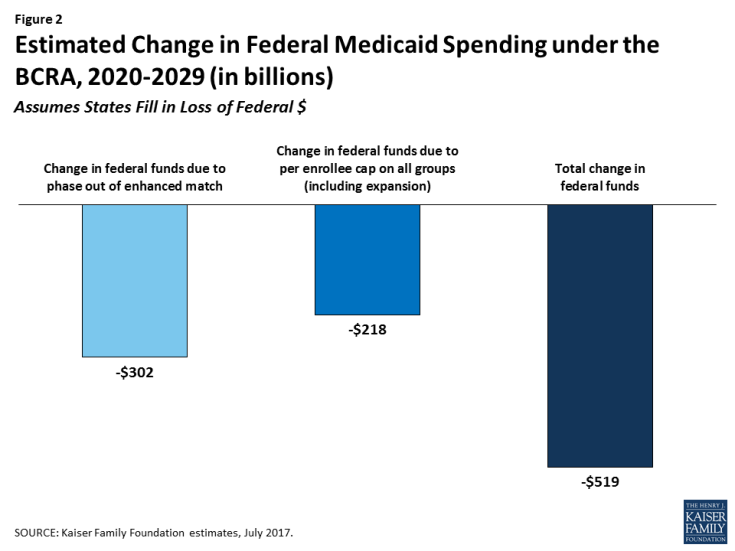

Our analysis shows that federal spending over the 2020-2029 period would be reduced by $519 billion if states fill in the loss of federal funds, a 10% reduction in federal funds compared to federal funding projections under current law. Of this amount, $302 billion is attributable to the phase-out of the enhanced FMAP for the expansion population and $218 billion from the per enrollee caps that apply to all enrollment groups, including expansion adults (Figure 2).

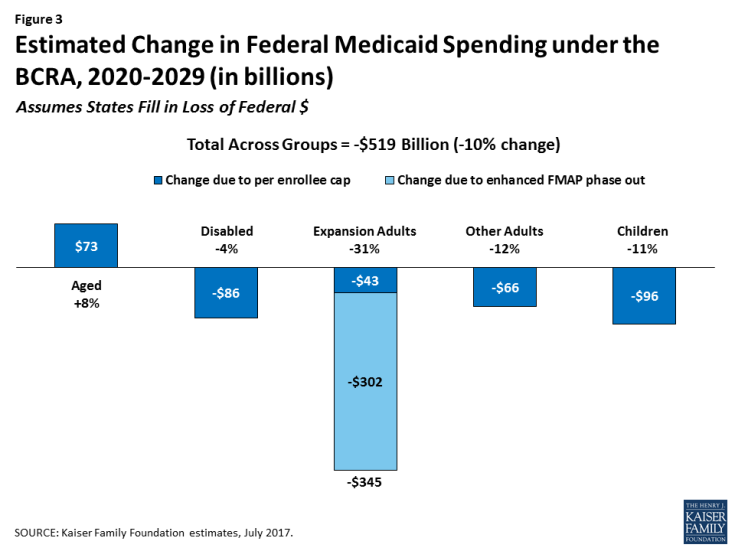

Examining the reductions by group shows that most of the federal reductions would be for spending for ACA expansion adults ($345 billion). This reduction is much larger than the reduction for other groups because it accounts for the phase-out of the enhanced matching funds as well as limiting growth on per enrollee spending. Together, these changes across all population groups would result in a 31% reduction in federal funds relative to spending under current law. Over the ten year period, per enrollee caps also would result in reductions in federal funding for all groups except for the aged (Figure 3).

Generally, prior to 2025, the per enrollee growth limits for the aged in the BCRA would be higher than anticipated growth in per enrollee costs under current law. This analysis assumes that states could use the higher amounts for the aged to offset lower spending in other groups. However, because states still need to match federal spending under the BCRA, it is unclear whether this will occur. If states do not provide additional state matching dollars to access these funds, then overall federal reductions could be $73.4 billion lower over the 2020-2029 period.

State-by-state changes would vary greatly depending on the current size of the state’s Medicaid program, its case mix of enrollment across eligibility groups, and whether or not the state expanded Medicaid under the ACA (Table 1).

Estimated Changes, 2029

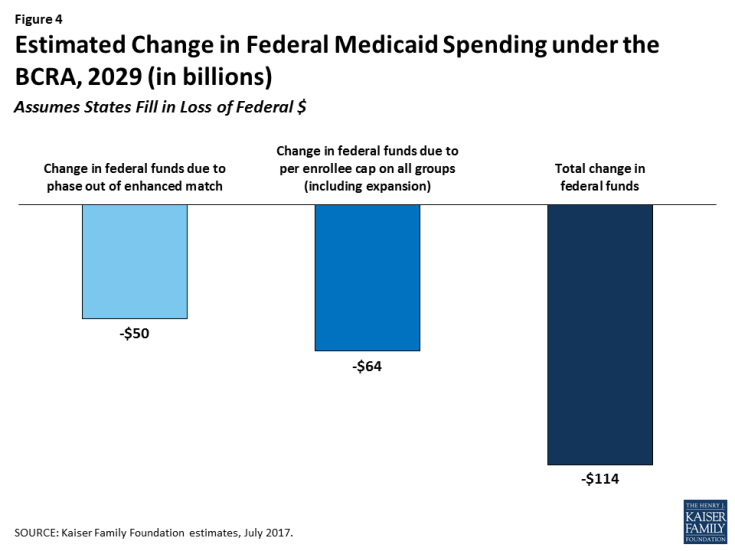

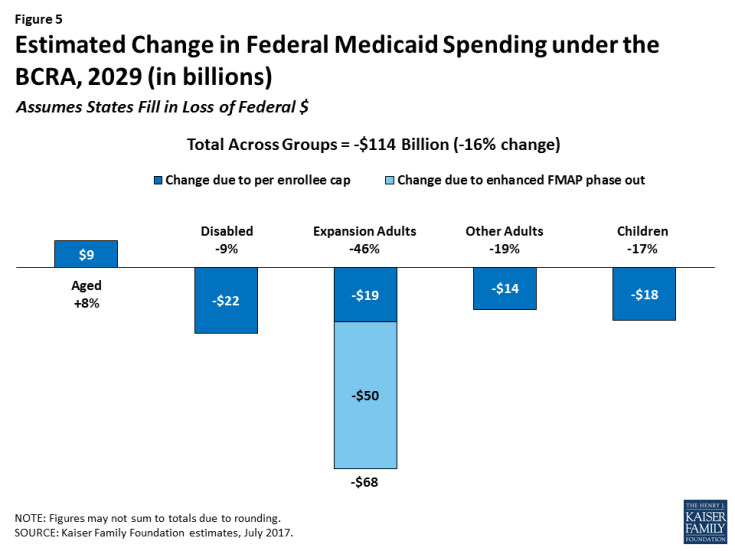

In the last year of our analysis, 2029, we estimate that the reductions in federal funds would be $114 billion (a 16% decline) if states maintain their programs. Of this amount, $50 billion is attributable to the phase-out of the enhanced FMAP for the expansion population and $64 billion from the per enrollee caps for all groups, including the expansion population (Figure 4 and Table 2). The relative contribution of the changes in FMAP and per enrollee cap changes over time, with the cap accounting for a larger share of the decline in federal dollars as per enrollee caps become more binding. This result is similarly seen in the estimates by eligibility group under Scenario 1 (Figure 5), which show that the reductions across groups in the last year would be a higher percentage reduction than over the ten-year period for all groups except the aged. Limits or caps in per enrollee spending for the aged would still not be binding in 2029, although caps would likely become binding for this group very soon after 2029 as growth per enrollee is limited to the CPI-U inflation factor. (Figure 5)

Estimated Changes if States Drop the ACA Medicaid Expansion

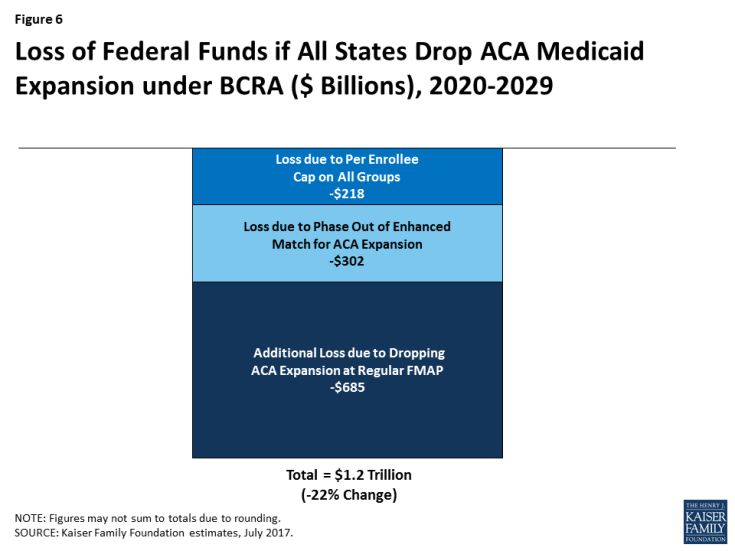

If states that expanded their Medicaid programs drop the expansion in response to the loss of enhanced federal financing, the change in federal funds to states relative to current law would be even larger. We estimate that states could forgo an additional $685 billion over the 2020-2029 period due to dropping their expansion (Figure 6 and Table 3), bringing the total decline in federal funds to $1.2 trillion. This total would be a 22% decline in federal spending relative to what would happen under current law. These estimates assume no other state responses to the law, such as cuts in provider rates or changes in scope of benefits; if states made other changes to their Medicaid programs, changes in federal spending relative to current law could be even larger. In 2029, states would forgo about an additional $80 billion in federal funds if they drop their expansion, leading to a total decline in federal funds of $194 billion. By 2029, we estimate that nearly 19 million people who would be covered in the expansion group could lose Medicaid coverage if states roll back the expansion, about a 19% drop in Medicaid enrollment. While some of these people may be able to purchase coverage through the individual market, it is likely that such coverage would have prohibitively high deductibles or cost sharing.

Figure 6: Loss of Federal Funds if All States Drop ACA Medicaid Expansion under BCRA ($ Billions), 2020-2029

Discussion

This analysis presents estimates of changes in federal Medicaid funds under the BCRA based on several assumptions. Actual outcomes under the proposed law may differ greatly due to a number of factors.

Uncertainty in inflation index projections. First, increases in federal per enrollee spending limits under the BCRA are based on the consumer price index. While we used current estimates of CPI-M and CPI-U in our analysis, there is uncertainty over what future inflation indices will actually be. If these inflation factors differ from current estimates, changes in federal Medicaid spending could be larger or smaller.

Uncertainty in future Medicaid growth. Similarly, there is substantial uncertainty around future growth rates in Medicaid under current law. We attempted to address this uncertainty by incorporating multiple projections of future growth in Medicaid enrollment and spending per enrollee by eligibility group into our estimates. One limitation of doing so is that existing projections for future Medicaid enrollment and spending are for all enrollees. Our analysis includes only full-benefit enrollees, as partial-benefit enrollees are exempt from the per enrollee caps under BCRA. In the past, per enrollee growth rates for full-benefit enrollees have been higher than those for all enrollees; if this pattern holds in the future as well, our estimates would be conservative, as future spending under current law would be higher than our estimates (leading to greater differences between current law and the BCRA).

We also applied the same growth rates to all states even though historical data indicates state variation in enrollment and spending growth rates. State-by-state changes in Medicaid spending are highly variable and reflect not only state environment but also one-time policy shifts; thus, future state-by-state changes in Medicaid spending are difficult to predict.

Other discretionary changes in BCRA. We do not model all Medicaid provisions in the BCRA, such as the exemption from the per enrollee cap for children who qualify for Medicaid based on a disability, the optional block grant for expansion and/or other adults, or the provisions to equalize state per enrollee spending over time. Several of these provisions give a great deal of discretion to states or to the Secretary, and it is difficult to predict how they will be implemented.

Additional behavioral responses. Finally, our analysis assumes no other changes in state Medicaid programs as a result of the BCRA other than those explicitly modeled. For example, if states spend over their federal limits under BCRA, they face subsequent penalties and thus have an incentive to stay within the limits. These incentives could lead states to make further reductions in Medicaid (in benefits or other spending) that we did not model. In addition, under a per capita cap, states have incentives to increase enrollment of “lower cost” enrollees in a given group and to decrease enrollment of “high-cost” enrollees. It is unclear how these incentives would affect overall Medicaid enrollment or spending patterns. While we examine two scenarios around the Medicaid expansion decision, it is possible that states would phase-out the expansion or end coverage at different times. These decisions would have national as well as state-by-state implications for federal funding.

While changes to Medicaid under the proposed legislation will be driven by choices at state level, state economies, and other factors going forward, these estimates provide a way to assess the policy challenges states would face if the BCRA provisions were enacted. In the early years of the new policy, declines in federal Medicaid dollars would be concentrated among expansion states largely due to the phase out of the enhanced funds for the ACA expansion. Over time, however, per enrollee caps become more binding, especially in later years when inflation rates are set at the same amount for all groups and all states, and cuts in federal spending affect all states.