Assessing PEPFAR’s Impact: Analysis of Economic and Educational Spillover Effects in PEPFAR Countries

Key Findings

PEPFAR, the U.S. global HIV program and the largest commitment by any nation to address a single disease in history. In addition to impacts on HIV, studies have shown that PEPFAR has had broader health impacts, including in the area of maternal and child health. Whether it has also had impacts beyond health, such as in broader economic and educational gains, is less known but could have important implications for the future of the program. If found to support these other areas, it suggests that investments in a vertical health program can have knock-on effects that support broader economic development goals and improvements, a finding that has particular relevance in an era of constrained aid budgets. Here, we examine PEPFAR’s association with five non-health outcomes: the GDP growth rate per capita; the share of girls and share of boys, respectively, who are out of school; and female and male employment rates. We find that:

- PEPFAR was associated with significant, positive improvement in three of the five measures assessed over the 2004-2018 period, while findings for the other two outcomes were inconclusive.

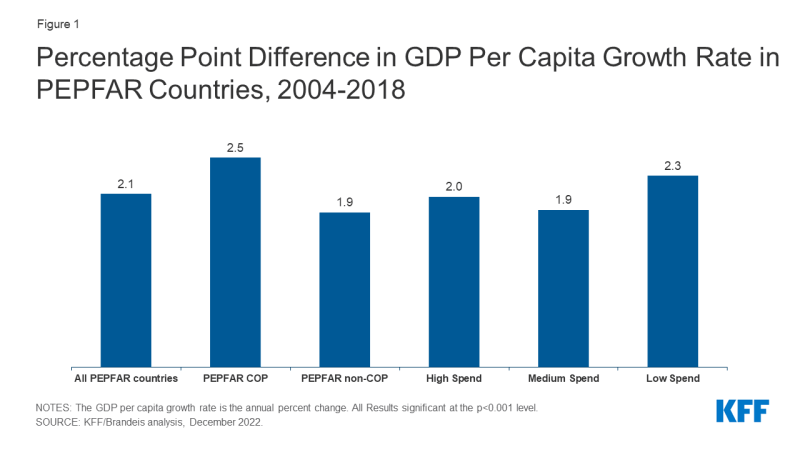

- PEPFAR countries experienced an increase in the GDP per capita growth rate that was greater than what would otherwise be expected in PEPFAR’s absence. Specifically, the growth rate was 2.1 percentage points higher over the period. This effect was greater in countries with “Country Operational Plans,” which engage in more intensive planning and generally have greater financial investment from PEPFAR.

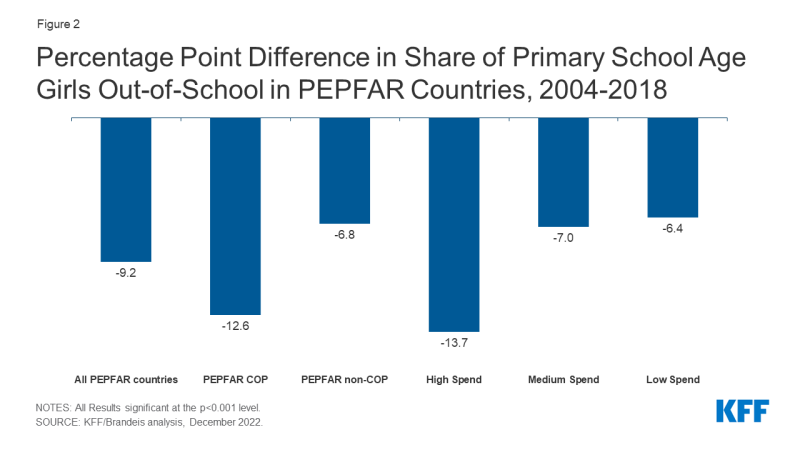

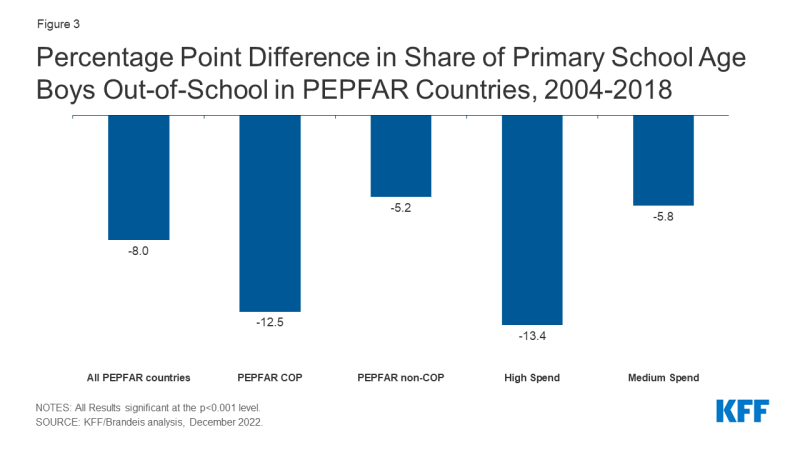

- In addition, the share of girls of primary school age who were not in school declined significantly over the period, falling by more than 9 percentage points, an effect that was greater in COP and high investment countries. This result was also found for boys – the share out of school fell by 8 percentage points.

- The was no significant effect detected on labor force participation for either females or males over the period.

- Overall, these findings further contribute to the evidence base that PEPFAR’s investments have been correlated with positive, non-health outcomes.

Introduction

PEPFAR is the largest commitment by any nation to address a single disease. Since its launch in 2003, the U.S. government has provided close to $90 billion in bilateral assistance to address HIV in low and middle income countries (LMICs), and PEPFAR has been credited with saving millions of lives and helping to change the trajectory of the global HIV epidemic. In a prior analysis, we found that PEPFAR has contributed to large, significant reductions in all-cause mortality, suggesting a mortality effect beyond HIV.1 More recently, we found that PEPFAR has had significant, positive, health spillover effects in the area of maternal and child health, including reductions in maternal and child mortality and increases in childhood immunization rates.2

Whether PEPFAR has also had any spillover effects beyond health, however, has been less studied, and, while such an impact is plausible, it is not a given. On the one hand, PEPFAR, as a vertical, disease-specific initiative, was not designed to be an economic or educational program, and its goals are HIV-focused and targeted. On the other, the program has recognized that providing economic and educational support, such as in its DREAMS program focused on adolescent girls and young women, is important for addressing the drivers of the HIV epidemic (although its direct support for such interventions is limited and only began after 2014).3,4 In addition, external aid may also act as a direct economic stimulus in countries, impacting their GDP.5 More broadly, studies have found that health investments are correlated with educational attainment and economic growth, including, for example, by enabling children to stay in school longer and by supporting adults to join and/or remain in the labor force.6 In this analysis, we seek to assess whether PEPFAR has had impacts beyond health by examining changes in five economic and educational outcomes in PEPFAR countries: the GDP growth rate; the share of girls and share of boys, respectively, who are out of school; and female and male employment rates (see Box). If PEPFAR is found to support these other areas, it suggests that investments in a vertical health program can have knock-on effects that support broader economic and development goals and improvements, a finding that has particular relevance in an era of constrained aid budgets.

| Box: Outcome Measures |

| 1. GDP per capita growth (annual % change)

2. Share of girls out of school 3. Share of boys out of school 4. Female employment rate 5. Male employment rate |

The existing literature on PEPFAR’s impact in these areas is limited though there is evidence of such an effect. In a study of 21 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, including 10 PEPFAR focus countries and 11 control countries, Wagner, Barofsky, and Sood found that PEPFAR was associated with a significant increase in male employment, though not with female employment, between 2004 and 2010.7 Kim and Whang, in a study of 15 PEPFAR focus and 121 control countries, found that PEPFAR was associated with increases in the GDP growth rate in focus countries between 2003 and 2009.8 Finally, an analysis by the Bipartisan Policy Center found that GDP per capita and average output per worker were higher in countries with greater PEPFAR investment compared to countries with low or no investment between 2004 and 2016.9 Other studies have looked more generally at the relationship between HIV interventions, particularly antiretroviral therapy, and economic outcomes, though not at PEPFAR’s role specifically, and also found positive correlations.10 No studies were identified that have examined the relationship between PEPFAR and educational attainment, although several have more generally assessed the impact of HIV on the education of children, demonstrating the epidemic’s deleterious effects.11

For the current analysis, we look at a larger set of countries and over a longer period of time than the prior analyses identified. We use a difference-in-difference quasi-experimental design to analyze the change in each of these outcomes in 90 PEPFAR countries between 2004, the first year in which PEPFAR funding began, and 2018, compared to a comparison group of 67 low- and middle- income countries (See methodology for more detail). We tested several different model specifications. Our final model controls for numerous baseline variables that may also be expected to influence these outcomes and which help to make the PEPFAR and non-PEPFAR country groups more comparable. Despite the strengths of the difference-in-difference model design, however, it is still possible that there may be other, unobservable ways in which comparison countries differed from PEPFAR countries which could account for our results. In addition, we are unable to determine causality, which could operate in either direction (e.g., better health results in greater economic growth or greater economic growth improves health), as has been noted in the broader health economics literature.12

Findings

We find that PEPFAR was positively associated with three of the five economic and educational outcomes examined, while its association with the remaining two is inconclusive:

Between 2004 and 2018, PEPFAR was associated with a 2.1 percentage point increase in the GDP growth rate per capita over the period, compared to what would have been expected in the absence of the program. This percentage point change translates into a 45.7% increase in the GDP per capita growth rate. Looking at the broader trend, prior to PEPFAR’s initiation, the GDP per capita growth rate in comparison countries was generally higher than the rate in PEPFAR countries. This pattern began to change just a few years after PEPFAR’s initiation, near the time of the 2008 global financial crisis, when the growth rate in comparison countries fell below that of PEPFAR countries. While it is possible that the financial crisis affected PEPFAR and comparison countries differently, our model is designed to control for this possibility. We also examined the period before 1999, given the volatility in the GDP growth rate in both PEPFAR and comparison countries, which appears to be influenced by a subset of outlier countries; after removing these countries from our analysis, the results remain significant (See Figure 1, Tables 5-6, and Appendix).

PEPFAR’s estimated effect on the GDP growth rate per capita over the period was even greater in “COP” countries. The increase in the GDP growth rate per capita was 2.5 percentage points in COP countries, or a 61.5% increase over the period. These countries engage in more intensive planning and programming by preparing an annual PEPFAR Country Operational Plan (COP), compared to other PEPFAR countries, and generally receive greater funding; indeed, countries with more intensive spending saw greater change than their comparisons (See Figure 1 and Tables 5-6).

PEPFAR was also associated with a decline of 9.2 percentage points in the out-of-school rate for girls of primary school over the period. This represents a decline in the share of girls not in school of 42.4%. This effect was strongest in COP countries and in countries with greater PEPFAR investment. The large time trend shows that, prior to PEPFAR, the share of girls out of school was much higher in PEPFAR countries, relative to comparison countries. Following the introduction of the program, these rates began to converge (see Figure 2, Tables 5-6, and Appendix).

Figure 2: Percentage Point Difference in Share of Primary School Age Girls Out-of-School in PEPFAR Countries, 2004-2018

Similarly, the share of boys of primary school age who were out-of-school also declined in PEPFAR countries, by 8 percentage points relative to what would be expected. This represents a decline of 43.1%. As with girls, the effect was stronger in COP countries and in countries with greater PEPFAR investment and the broader trend was similar to that of girls (see Figure 3, Tables 5-6, and Appendix).

Figure 3: Percentage Point Difference in Share of Primary School Age Boys Out-of-School in PEPFAR Countries, 2004-2018

By contrast, PEPFAR’s effect on employment rates for both females and males is inconclusive. Our findings for employment rates for females and males, respectively, were not statistically significant (we only report final results significant at the p < 0.001 level). More generally, the rates of employment for both females and males were essentially flat over the entire 1990-2018 period for PEPFAR and comparison countries (and higher for female employment in PEPFAR countries even before PEPFAR’s initiation). (see Tables 5-6 and Appendix).

Implications

Our findings confirm the prior literature demonstrating a relationship between PEPFAR and economic growth.13 We show that these impacts are most pronounced in COP countries, which also receive the highest levels of PEPFAR investment. These effects could be due to the direct economic stimulus of PEPFAR assistance on low and middle income economies; in general, PEPFAR funding as a share of GDP in COP countries was under one percent in most years, though in some, it ranged between 1-2%.14 We also demonstrate the impacts of PEPFAR on two measures not previously reported in the literature – a decrease in the share of girls and of boys, of primary school age, who were out-of-school. Again, PEPFAR impacts were greatest in COP countries. We do not, however, find evidence of a relationship between PEPFAR and rates of employment for females and males (our findings were not significant). While increases in both GDP growth rates and educational engagement may be expected to result in increased labor participation, such impacts may take many years before they become evident or may be influenced by other factors. Still, this area warrants further exploration.

While our findings regarding GDP growth rates per capita and educational engagement are strong, and despite the strengths of the difference-in-difference model design, it is possible that there may be other, unobservable ways in which comparison countries differed from PEPFAR countries, which could account for our results. As mentioned above, for example, it is possible that the financial crisis affected PEPFAR and comparison countries differently, although our model design attempts to control for this possibility. In addition, it is possible that patterns within a subset of countries could be driving the overall trend. Future analysis could seek to explore other factors that may contribute to these findings as well as the country-level effects for these measures. It could also further explore the different pathways that may help to explain the relationships between PEPFAR support and improved economic and educational outcomes.

Overall, these findings further contribute to the evidence base that PEPFAR’s investments have also been correlated with positive, non-health outcomes. Given tight budgets and ongoing questions about the future trajectories of global health efforts more broadly and PEPFAR specifically, such findings indicate that a large, vertical health program which has been shown to have significant health impacts, may also contribute to broader economic and development goals.

Methods

We used a difference-in-difference15, quasi-experimental design to estimate a “treatment effect” (PEPFAR), compared to a group without the intervention (the counterfactual). The difference-in-difference design compares the before and after change in outcomes for the treatment group to the before and after change in outcomes for the comparison group. We constructed a panel data set for 157 low- and middle- income countries between 1990 and 2018. Our PEPFAR group included 90 countries that had received PEPFAR support (between 2004 and 2018). Our comparison group included 67 low- and middle-income countries that had not received any PEPFAR support or had received minimal PEPFAR support (<$1M over the period or <$.05 per capita) between 2004 and 2018. The pre-intervention period was 1990 to 2003 and post intervention period was 2004 to 2018. Data on PEPFAR spending by country were obtained from the U.S. government’s https://foreignassistance.gov/ database and represent U.S. fiscal year disbursements; data for other measures were obtained from the World Bank’s World Development Indicator database and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) database, unless otherwise noted. Our outcomes of interest, their definitions, and sources are listed in Table 1. Baseline variables (for 2004) and sources are listed in Table 2 and model specifications examined in Table 3. Table 4 provides baseline means for all outcome variables. Final results are presented in Tables 5-6.

| Table 1: Outcome Variables | |

| Variable | Definition |

| 1. GDP per capita growth (annual %) | Annual percentage growth rate of GDP per capita based on constant local currency. GDP per capita is gross domestic product divided by midyear population. |

| 2. Children out of school, female (% of female primary school age) | Percentage of female primary-school-age children who are not enrolled in primary or secondary school. |

| 3. Children out of school, male (% of male primary school age) | Percentage of male primary-school-age children who are not enrolled in primary or secondary school. |

| 4. Employment to population ratio, 15+, female (%) | Proportion of a country’s female population that is employed, defined as persons of working age who, during a short reference period, were engaged in any activity to produce goods or provide services for pay or profit, whether at work during the reference period (i.e. who worked in a job for at least one hour) or not at work due to temporary absence from a job, or to working-time arrangements. |

| 5. Employment to population ratio, 15+, male (%) | Proportion of a country’s male population that is employed, defined as persons of working age who, during a short reference period, were engaged in any activity to produce goods or provide services for pay or profit, whether at work during the reference period (i.e. who worked in a job for at least one hour) or not at work due to temporary absence from a job, or to working-time arrangements. |

| Source: World Bank, WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ | |

| Table 2: Baseline Variables, 2004 | |

| Variable | Data Source |

| 1. GDP per capita (current USD) | WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ |

| 2. Recipient of U.S. HIV funding prior to 2004 (dummy variable) | USAID, https://foreignassistance.gov/ |

| 3. Total population | United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Population Prospects 2019, Online Edition. Rev, https://population.un.org/wpp/ |

| 4. Life expectancy at birth (years) | WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ |

| 5. Total fertility rate (births per woman) | WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ |

| 6. Percent urban population (of total population) | WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ |

| 7. School enrollment, secondary (% gross) | WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ |

| 8. WB country income classification | World Bank, https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups |

| 9. HIV prevalence (% of population wages 15-49) | WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ (from UNAIDS); The Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network, Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2020, http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool. |

| 10. Per capita donor spending on health (non-PEPFAR) (constant $) | OECD Creditor Reporting System database, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=crs1 |

| 11. Per capita domestic health spending, government and private, PPP (current $) | WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ |

We explored several difference-in-difference model specifications, compared to an unadjusted model (see Table 3). Each specification controlled for numerous baseline variables that may be expected to influence the outcome of interest to help make the non-PEPFAR group more comparable to the PEPFAR group. Baseline means for outcome variables are provided in Table 4. Final results are presented in Tables 5-6 and are from model specification #3, and significance is only reported in the analysis for results at the p<0.001 level. The appendix provides trend data for each outcome variable in PEPFAR and comparison countries over the full study period.

–

| Table 3: Model Specifications | |

| Model | Difference-in Difference Specification |

| 1 | Unadjusted model |

| 2 | Includes baseline variables 1-9 |

| 3 | Includes baseline variables 1-11 |

| 4 | Includes baseline variables 1-9 and yearly per capita donor spending on health (non-PEPFAR) by all donors |

Despite the strengths of the difference-in-difference design, there are limitations to this approach. While we adjusted for numerous baseline factors that could be correlated with our outcomes of interest, there may be other, unobservable factors that are not captured here. Similarly, while our baseline factors are also intended to adjust for selection bias, there may be other ways in which comparison countries differed from PEPFAR countries (and factors which influenced which countries received PEPFAR support), which could bias the estimates.

–

| Table 4: Baseline Means, PEPFAR Countries, 2004 | ||||||

| Outcome Measure | All PEPFAR countries | COP countries | Non-COP countries | High spending | Medium spending | Low spending |

| GDP Per Capita growth (% change) | 4.5 | 4.1 | 4.8 | 3.3 | 5.6 | 4.7 |

| Primary Age Females Out of School (%) | 21.7 | 21.3 | 21.9 | 26.0 | 15.5 | 26.0 |

| Primary Age Males Out of School (%) | 18.5 | 19.1 | 18.1 | 23.7 | 12.5 | 20.9 |

| Female Employment (%) | 50.7 | 56.2 | 47.7 | 55.0 | 50.8 | 46.1 |

| Male Employment (%) | 69.8 | 70.9 | 69.2 | 70.2 | 68.1 | 71.1 |

| Table 5: Estimates of PEPFAR’s Impact by Measure, 2004-2018

(Percentage point difference-in-difference from means; standard errors in parentheses) |

||||||

| Outcome Measure | All PEPFAR countries | COP countries | Non-COP countries | High spending | Medium spending | Low spending |

| GDP per capita growth (% change) | 2.072*** | 2.504*** | 1.853*** | 2.037*** | 1.882*** | 2.288*** |

| (0.434) | (0.615) | (0.499) | (0.582) | (0.569) | (0.569) | |

| Primary Age Females Out of School (%) | -9.185*** | -12.580*** | -6.781*** | -13.663*** | -6.969*** | -6.352*** |

| (1.143) | (1.304) | (1.134) | (1.439) | (1.437) | (1.479) | |

| Primary Age Males Out of School (%) | -7.962*** | -12.508*** | -5.196*** | -13.374*** | -5.766*** | -4.336** |

| (1.031) | (1.171) | (1.029) | (1.302) | (1.301) | (1.338) | |

| Female Employment (%) | -2.416* | -3.313** | -1.952 | -1.763 | -3.601** | -1.777 |

| (0.991) | (1.102) | (1.013) | (1.298) | (1.258) | (1.284) | |

| Male Employment (%) | -1.657** | -1.650* | -1.660* | -1.180 | -2.582** | -1.125 |

| (0.625) | (0.644) | (0.694) | (0.814) | (0.788) | (0.805) | |

| ***p < 0.001 **p < 0.01 *p < 0.05 | ||||||

| Table 6: Estimates of PEPFAR’s Impact by Measure, 2004-2018(Percent change from Mean) | ||||||

| Outcome Measure | All PEPFAR countries | COP countries | Non-COP countries | High spending | Medium spending | Low spending |

| GDP Per Capita (% change) | 45.7%*** | 61.5%*** | 38.7%*** | 62.1%*** | 33.4%*** | 49.1%*** |

| Primary Age Females Out of School (%) | -42.4%*** | -59.2%*** | -31.0%*** | -52.5%*** | -44.9%*** | -24.5%*** |

| Primary Age Males Out of School (%) | -43.1%*** | -65.3%*** | -28.7%*** | -56.3%*** | -46.1%*** | -20.8%** |

| Female Employment (%) | -4.8%* | -5.9%** | -4.1% | -3.2% | -7.1%** | -3.9% |

| Male Employment (%) | -2.4%** | -2.3%* | -2.4%* | -1.7% | -3.8%** | -1.6% |

| ***p < 0.001 **p < 0.01 *p < 0.05 | ||||||

Jen Kates is with KFF. William Crown, Allyala Nandakumar, Gary Gaumer and Dhwani Hariharan are with Brandeis University.