Assessing PEPFAR’s Impact: Analysis of Maternal and Child Health Spillover Effects in PEPFAR Countries

Key Findings

PEPFAR, the U.S. global HIV program and largest commitment by any nation to address a single disease, was designed as a vertical, singularly-focused, global HIV initiative. While credited with helping to change the trajectory of the global HIV epidemic, some have argued that PEPFAR, and other vertical initiatives, risk “crowding out” other health investments, potentially resulting in worse, non-HIV-related health outcomes, while others have argued the opposite. In our recent analysis, which looked over the full course of the program, we found that PEPFAR was associated with large, significant declines in overall mortality in countries that received its support, suggesting a positive spillover effect of the program beyond HIV. Here, we look at seven maternal and child health measures to further assess this relationship. PEPFAR’s potential impact in this area is plausible, given its investment in the health workforce, laboratory services, and other aspects of health systems strengthening, estimated to total more than $1 billion per year, and its increased emphasis on reaching women where they receive prenatal care and seek immunizations and other services for their children. We analyze the change in these measures in 90 PEPFAR recipient countries between 2004-2018 compared to similar low- and middle-income countries. Our main findings are as follows:

- PEPFAR was associated with significant, positive improvement in six of the seven maternal and child health measures assessed.

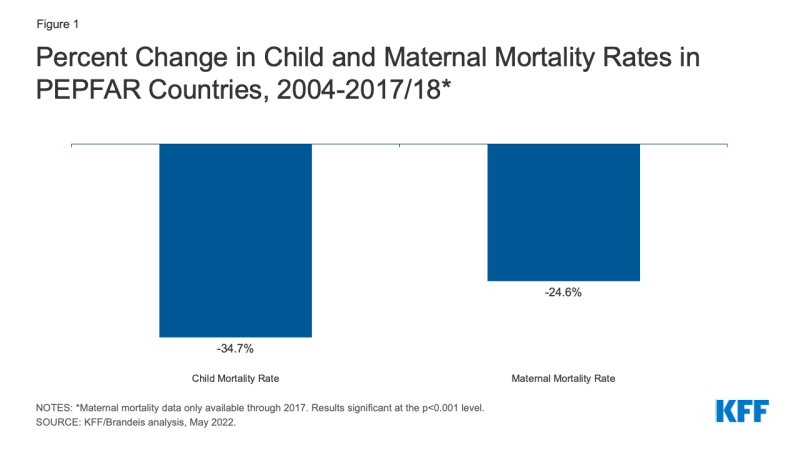

- Specifically, PEPFAR countries experienced large, significant reductions in both maternal and child mortality, relative to what would have been expected in PEPFAR’s absence, over the course of the program. The child mortality rate was reduced by 35% and the maternal mortality rate was reduced by 25%. These effects were strongest where PEPFAR engages in more intensive planning and programming and invests more funding.

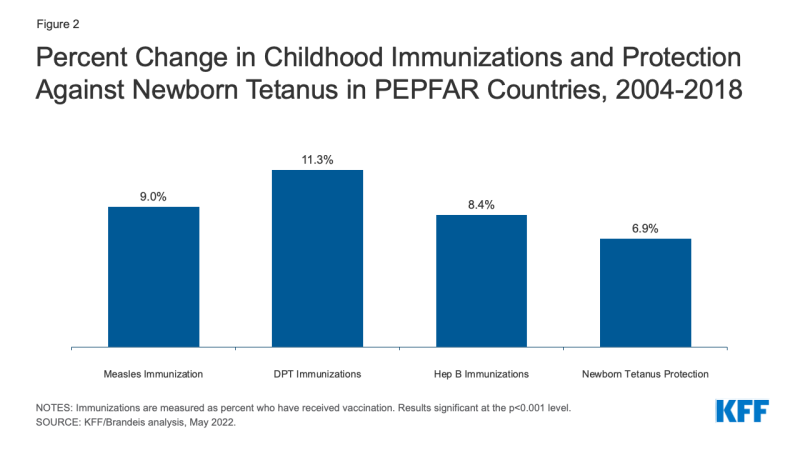

- PEPFAR countries also experienced significant increases in childhood immunization rates in three areas – measles immunization (a 9% increase), DPT immunization (11%), and Hepatitis B immunization (8%) – and an increase in the percent of newborns protected against tetanus because their mothers were immunized against the disease (7%).

- There was no significant association found between PEPFAR and the prevalence of anemia among women of reproductive age.

- Taken together, these findings add to the evidence base that PEPFAR has had positive health spillover effects beyond just HIV, with no negative, “crowding-out” effects. As policymakers and others consider the future of the program, these findings can help to inform their discussions about how PEPFAR can best continue to reach HIV goals and contribute to broader health gains.

Introduction

PEPFAR, the U.S. global HIV program and largest commitment by any nation to address a single disease, was designed as a vertical, singularly-focused, global HIV initiative. In many countries, PEPFAR funding represents the largest external health investment of any donor, and often surpasses domestic HIV spending.1 While credited with saving millions of lives and helping to change the trajectory of the global HIV epidemic, some have argued that PEPFAR, and other vertical initiatives, could risk “crowding out”, or displacing, other health investments and efforts, potentially resulting in worse, non-HIV-related health outcomes.2 Others have argued that PEPFAR’s investments over time contribute to the broader health system.3 In both cases, most of the literature is from a decade or more ago. In our recent analysis4, we examined PEPFAR’s impact through 2018 and found that it was associated with large, significant declines in overall mortality, suggesting a positive spillover effect beyond HIV. Here, working with researchers at Brandeis University, we use a quasi-experimental design to look at seven maternal and child health measures to further assess whether there were other health spillover effects, either positive or negative, in PEPFAR countries over this period.

Maternal and child health is an important area to examine. First, prior studies of PEPFAR’s association with such measures have found mixed results.5 Second, poor maternal and child health outcomes have presented ongoing challenges, concurrent with HIV, in low and middle income countries. Lastly, improving maternal and child health is a main target of the Sustainable Development Goals and of the U.S. government’s global health efforts.6 If PEPFAR is shown to have positive spillover effects on maternal and child health, it would suggest that HIV investments have yielded bigger dividends and that the program has served as a wider platform. However, if negative spillover effects are detected, it would suggest that PEPFAR investments may have worked at cross-purposes with these other health areas, diverting resources with detrimental results.

While PEPFAR does not directly fund non-HIV specific maternal and child health services, its potential impact in the area of maternal and child health is plausible given its significant investments in the health workforce, laboratory services, and other aspects of health systems strengthening, estimated to total more than $1 billion per year.7 Indeed, attention to the importance of strengthening the underlying health systems in the countries in which it works was specified in its original authorizing legislation8 and its first Congressionally-mandated strategy.9 This emphasis has been enhanced over time, particularly starting with PEPFAR’s 2008 reauthorization.10,11 Its current guidance to countries, used to prepare their annual programmatic and budgeting plans, states that “Plans should ensure that PEPFAR’s actions are supporting enduring public health systems and capabilities. That is, people and systems that serve the PEPFAR mission, but are trained and designed to be resilient public health assets for a long-term public health response to HIV, which can be adapted for responses to other public health threats and emergencies.”12 In addition, as part of PEPFAR’s effort to address HIV among women, particularly pregnant women, and children, it has increasingly emphasized reaching women where they receive prenatal care and seek immunizations and other services for their children, and on integrating services.13,14 Guidance provided to countries as early as 2006, for example, included the importance of providing routine childhood immunizations to children with HIV and stated that PEPFAR funds could be used for linking to immunization programs and referral and follow-up for immunization15 and country guidance has continued to encourage such linkages.

| Box: Outcome Measures |

| 1. Child mortality rate 2. Maternal mortality ratio 3. Measles immunization 4. DPT immunizations 5. HepB3 immunizations 6. Newborns protected against tetanus 7. Prevalence of anemia among women of reproductive age |

For this analysis, we identified seven maternal and child health outcome measures16 (see Box). These measures were chosen because they represent global health target areas and because sufficient data were available for analysis. We used a difference-in-difference, quasi-experimental design to analyze the change in each measure in 90 PEPFAR countries between 2004, the first year in which PEPFAR funding began, and 2018, compared to a comparison group of 67 low- and middle-income countries. We tested several model specifications. Our final model specification controls for numerous baseline variables that may also be expected to influence the health outcomes examined and which help to make the non-PEPFAR group more comparable to the PEPFAR group. However, despite the strengths of the difference-in-difference model design, it is still possible that there may be other, unobservable ways in which comparison countries differed from PEPFAR countries, which could account for our results. (See methodology for more detail).

Findings

Between 2004 and 2018, PEPFAR was associated with significant, positive improvement in six of the seven maternal and child health measures assessed. These include both mortality measures and all but one immunization measure. There was no evidence of any negative, spillover effect.

The largest effects of PEPFAR’s investments were found in reductions in the child mortality rate. The child mortality rate was 34.7% lower in PEPFAR countries compared to what would have been expected if PEPFAR had been absent. These effects were greater in countries with more intensive planning and programming through the PEPFAR “COP” process17, which are also countries with greater investment. Because we did not assess the independent effect of PEPFAR spending in COP countries, it is unclear if mortality declines were due to greater spending, more intensive planning and programming, or some combination of both. (See Figure 1 and Tables 5-6).

The maternal mortality rate also declined significantly in PEPFAR countries, though not as steeply. Between 2004 and 2017 (the most recent year for which maternal mortality data were available), the maternal mortality rate was 24.6% lower than would have been expected. As with child mortality, these effects were greater18 in countries with more intensive planning and greater PEPFAR investment (see Figure 1 and Tables 5-6).

PEPFAR was also associated with significant improvements in childhood immunization rates in three areas – measles; diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DPT); and Hepatitis B – and with increased protection against newborn tetanus. In each of these areas, PEPFAR countries saw greater increases in immunization against disease than would have been expected in PEPFAR’s absence. Measles immunization rates among children increased by 9%, DPT immunization by 11.3%, and Hepatitis B immunization by 8.4%. In addition, the percent of newborns protected against neonatal tetanus because their mothers were immunized against the disease increased by 6.9% (see Figure 2 and Tables 5-6). Spending intensity and planning, however, were not consistently correlated with greater increases or significantly different from what would have been expected.

Figure 2: Percent Change in Childhood Immunizations and Protection Against Newborn Tetanus in PEPFAR Countries, 2004-2018

PEPFAR was not associated with the final measure of maternal and child health assessed. The prevalence of anemia among women of reproductive age did decrease but this decline was not significant (see Tables 5-6).

Implications

These findings, which cover a longer time period than prior studies, add to the evidence base that PEPFAR has had positive health spillover effects, beyond just HIV. Our findings are particularly strong for child and maternal mortality, some of which likely capture reductions in HIV-related mortality itself but extend beyond these. For example, HIV accounted for 5.1% of the estimated 4 million child deaths in sub-Saharan Africa in 2003, compared to 1.6% of the estimated 2.8 million child deaths in 2018, a drop that would not fully drive the overall decline in child mortality.19 Similarly, HIV, which is not considered to be a direct cause of maternal mortality, was estimated to have accounted for 6.4% of maternal deaths in sub-Saharan Africa between 2003 and 2009.20 Beyond mortality, significant improvements were also found in several immunizations that protect children from disease. Additionally, we find no evidence of any negative, “crowding-out” effect of PEPFAR in maternal and child health.

Still, it is important to note that despite the strengths of the model design used here, it is possible that there may be other, unobservable ways in which comparison countries differed from PEPFAR countries, which could account for our results. Future analysis could seek to explore other factors that may contribute to these findings. It could also further explore the multiple and complex pathways that may help to explain the relationships between PEPFAR support and improved maternal and child health outcomes, and examine the change in other non-HIV specific health measures in PEPFAR countries over time.

Taken together, these findings indicate that U.S. investments in PEPFAR, which have altered the trajectory of the HIV epidemic, saving millions of lives, have also paid significant dividends beyond HIV alone. As policymakers and others consider the future of the program, these findings can help to inform their discussions about how PEPFAR can best continue to reach HIV goals and contribute to broader health gains.

Methods

We used a difference-in-difference21, quasi-experimental design to estimate a “treatment effect” (PEPFAR), compared to a group without the intervention (the counterfactual). The difference-in-difference design compares the before and after change in outcomes for the treatment group to the before and after change in outcomes for the comparison group. We constructed a panel data set for 157 low- and middle- income countries between 1990 and 2018. Our PEPFAR group included 90 countries that had received PEPFAR support (between 2004 and 2018). Our comparison group included 67 low- and middle-income countries that had not received any PEPFAR support or had received minimal PEPFAR support (<$1M over the period or <$.05 per capita) between 2004 and 2018. The pre-intervention period was 1990 to 2003 and post intervention period was 2004 to 2018 for all measures except maternal mortality (2000-2003 and 2004-2017) and prevalence of anemia among women of reproductive age (1990-2003 and 2004-2016), due to data limitations. Data on PEPFAR spending by country were obtained from the U.S. government’s https://foreignassistance.gov/ database and represent U.S. fiscal year disbursements; data for other measures were obtained from the World Bank’s World Development Indicator database and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), unless otherwise noted. Our outcomes of interest, their definitions, and sources are listed in Table 1. Baseline variables and sources are listed in Table 2.

| Table 1: Outcome Variables | |

| Variable | Definition |

| 1. Child mortality rate | Probability of a child dying between birth and 5 years of age, per 1,000 live births. |

| 2. Maternal mortality ratio | Number of women who die from pregnancy-related causes while pregnant or within 42 days of pregnancy termination per 100,000 live births |

| 3. Measles immunization | Percent of children ages 12-23 months who received the measles vaccination |

| 4. DPT immunizations | Percent of children ages 12-23 months who received DPT vaccinations (3 doses) |

| 5. HepB3 immunizations | Percent of children ages 12-23 months who received hepatitis B vaccinations (3 doses) |

| 6. Newborns protected against tetanus | Percentage of births by women of child-bearing age who are immunized against tetanus |

| 7. Prevalence of anemia among women of reproductive age | Prevalence of anemia among women of reproductive age (% of women ages 15-49) |

| Source: World Bank, WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ | |

| Table 2: Baseline Variables, 2004 | |

| Variable | Data Source |

| 1. GDP per capita (constant USD) | WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ |

| 2. Recipient of U.S. HIV funding prior to 2004 (dummy variable) | USAID, https://foreignassistance.gov/ |

| 3. Total population | United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Population Prospects 2019, Online Edition. Rev, https://population.un.org/wpp/ |

| 4. Life expectancy at birth (years) | WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ |

| 5. Total fertility rate (births per woman) | WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ |

| 6. Percent urban population (of total population) | WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ |

| 7. School enrollment, secondary (% gross) | WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ |

| 8. WB country income classification | World Bank, https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups |

| 9. HIV prevalence (% of population ages 15-49) | WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ (from UNAIDS); The Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network, Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2020, http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool. |

| 10. Per capita donor spending on health (non-PEPFAR) (constant $) | OECD Creditor Reporting System database, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=crs1 |

| 11. Per capita domestic health spending, government and private, PPP (current $) | WDI, https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/ |

| 12. Measles prevalence in under 5 population (measles immunization models only) | IHME, http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool |

| 13. Diphtheria prevalence in under 5 population (DPT immunization models only) | IHME, http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool |

| 14. Whooping cough prevalence in under 5 population (DPT immunization models only) | IHME, http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool |

| 15. Tetanus prevalence in under 5 population (DPT immunization models only) | IHME, http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool |

| 16. Hepatitis B prevalence in under 5 population (HepB3 immunization models only) | IHME, http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool |

We explored several difference-in-difference model specifications, compared to an unadjusted model (see Table 3). Each specification controlled for numerous baseline variables that may be expected to influence the outcome of interest to help make the non-PEPFAR group more comparable to the PEPFAR group. Baseline means for outcome variables are provided in Table 4. Final results are presented in Tables 5-6 and are from model specification #3, and significance is only reported in the analysis for results at the p<0.001 level. Other model specifications generally produced similar results, with the exception of one model that included other donor spending on health as an annual variable; this may be due to the potential confounding of this measure with PEPFAR spending itself. The appendix provides trend data for each outcome variable in PEPFAR and comparison countries over the full study period.

| Table 3: Model Specifications | |

| Model | Difference-in Difference Specification |

| 1 | Unadjusted model |

| 2 | Includes baseline variables 1-9 (and an additional baseline variable for disease incidence, 12-16, depending on outcome measure) |

| 3 | Includes baseline variables 1-11 (and an additional baseline variable for disease incidence, 12-16, depending on outcome measure) |

| 4 | Includes baseline variables 1-9 (and an additional baseline variable for disease prevalence, 12-16, depending on outcome measure) and yearly per capita donor spending on health (non-PEPFAR) by all donors |

Despite the strengths of the difference-in-difference design, there are limitations to this approach. While we adjusted for numerous baseline factors that could be correlated with our outcomes of interest, there may be other, unobservable factors that are not captured here. Similarly, while our baseline factors are also intended to adjust for selection bias, there may be other ways in which comparison countries differed from PEPFAR countries (and factors which influenced which countries received PEPFAR support), which could bias the estimates.

| Table 4: Baseline Means, PEPFAR Countries, 2004 | ||||||

| Outcome Measure | All PEPFAR countries | COP countries | Non-COP countries | High spending | Medium spending | Low spending |

| Child Mortality Rate | 78.9 | 97.9 | 68.9 | 99.5 | 71.8 | 65.4 |

| Maternal Mortality Rate | 409.8 | 497.5 | 363.7 | 519.6 | 345.5 | 364.4 |

| Measles Immunization | 77.5 | 74.5 | 79.1 | 72.9 | 79.9 | 79.7 |

| DPT Immunizations | 78.0 | 74.2 | 79.9 | 74.8 | 80.1 | 79.0 |

| Hepatitis B Immunizations | 79.1 | 74.4 | 81.7 | 80.7 | 78.3 | 78.5 |

| Anemia among women of reproductive age | 37.0 | 39.0 | 36.0 | 38.6 | 36.3 | 36.2 |

| Newborns protected against tetanus | 75.7 | 75.6 | 75.8 | 75.1 | 78.3 | 74.2 |

| Table 5: Estimates of PEPFAR’s Impact by Measure, 2004-2018 (Percent change from Mean) | ||||||

| Outcome Measure | All PEPFAR countries | COP countries | Non-COP countries | High spending | Medium spending | Low spending |

| Child Mortality Rate | -34.7%*** | -36.4%*** | -33.6%*** | -40.5%*** | -30.4%*** | -32.4%*** |

| Maternal Mortality Rate | -24.6%*** | -26.3%*** | -23.5%*** | -26.1%*** | -29.0%*** | -18.9%*** |

| Measles Immunization | 9.0%*** | 10.0%*** | 8.3%*** | 9.5%*** | 6.7%*** | 10.8%*** |

| DPT Immunizations | 11.3%*** | 11.2%*** | 11.1%*** | 12.5%*** | 8.7%*** | 12.8%*** |

| Hepatitis B Immunizations | 8.4%*** | 18.3%*** | 4.5%* | 9.8%** | 7.5%** | 6.9%* |

| Anemia among women of reproductive age | -2.8% | -4.1%* | -2.1% | -5.7%** | -2.0% | -0.7% |

| Newborns protected against tetanus | 6.9%*** | 4.9%* | 8.4%*** | 7.1%** | 6.3%** | 7.3%** |

| ***p < 0.001 **p < 0.01 *p < 0.05 | ||||||

| Table 6: Estimates of PEPFAR’s Impact by Measure, 2004-2018 (Percentage point difference-in-difference from means; standard errors in parentheses) |

||||||

| Outcome Measure | All PEPFAR countries | COP countries | Non-COP countries | High spending | Medium spending | Low spending |

| Child Mortality Rate | -27.383*** | -35.668*** | -23.168*** | -40.243*** | -21.807*** | -21.179*** |

| (1.424) | (1.694) | (1.426) | (1.898) | (1.835) | (1.855) | |

| Maternal Mortality Rate | -100.742*** | -130.898*** | -85.399*** | -135.678*** | -100.044*** | -68.936*** |

| (15.131) | (13.809) | (15.927) | (20.151) | (19.495) | (19.701) | |

| Measles Immunization | 6.946*** | 7.462*** | 6.560*** | 6.947*** | 5.339*** | 8.571*** |

| (0.748) | (0.894) | (0.772) | (1.006) | (0.984) | (0.983) | |

| DPT Immunizations | 8.810*** | 8.693*** | 8.889*** | 9.350*** | 6.999*** | 10.113*** |

| (0.705) | (0.830) | (0.729) | (0.946) | (0.925) | (0.925) | |

| Hepatitis B Immunizations | 6.667*** | 13.641*** | 3.638* | 7.875** | 5.901** | 5.385* |

| (1.545) | (2.102) | (1.674) | (2.436) | (2.011) | (2.220) | |

| Anemia among women of repro. age | -1.023 | -1.581* | -0.740 | -2.184** | -0.724 | -0.252 |

| (0.550) | (0.702) | (0.556) | (0.736) | (0.712) | (0.720) | |

| Newborns protected against tetanus | 5.240*** | 3.736* | 6.393*** | 5.338** | 4.921** | 5.398** |

| (1.300) | (1.472) | (1.403) | (1.534) | (1.653) | (1.606) | |

| ***p < 0.001 **p < 0.01 *p < 0.05 | ||||||