As Pandemic-Era Policies End, Medicaid Programs Focus on Enrollee Access and Reducing Health Disparities Amid Future Uncertainties

Results from an Annual Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2024 and 2025

Overview

This annual Medicaid budget survey report highlights certain policies in place in state Medicaid programs in state fiscal year (FY) 2024 and policy changes implemented or planned for FY 2025. The findings are drawn from the 24th annual budget survey of Medicaid officials conducted by KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA), in collaboration with the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD).

Medicaid budget survey reports from prior years are available in our archives.

NEWS RELEASE

- A news release announcing the publication of the 2024 Medicaid Budget Survey is available.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The Executive Summary provides an overview of the 2024 survey results and is available under the Executive Summary.

FULL REPORT

- The complete 2024 Medicaid Budget Survey Report is available under the Report. The Report contains 6 separate sections. Users can view each section separately or download a full Report PDF that is available on the right side of the page.

ENROLLMENT & SPENDING BRIEF

- This companion issue brief provides an overview of Medicaid enrollment and spending growth with a focus on FY 2024 and FY 2025.

ADDITIONAL BRIEFS

- Additional briefs using 2024 Medicaid budget survey data are published separately:

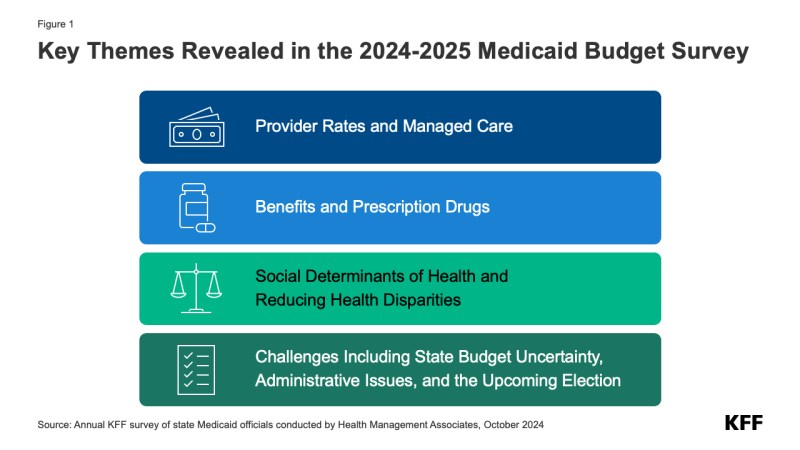

Executive Summary

At the end of state fiscal year (FY) 2024 and heading into FY 2025, states were wrapping up the unwinding of the pandemic-related continuous enrollment provision, focusing on an array of other priorities, and facing uncertainty about the stability of state revenues. States were also looking ahead to federal and state elections in November and the potential implications of those elections for Medicaid enrollees, states, and providers. As states have emerged from the now-expired COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, which profoundly affected Medicaid enrollment and spending, many are focused on using Medicaid to address long-standing health disparities (often exacerbated by the pandemic), improve access to behavioral health services and long-term services and supports (LTSS), address enrollee social determinants of health, and implement broader delivery system and value-based initiatives. Serving over one in five people living in the United States and accounting for nearly one-fifth of health care spending (and half of long-term care spending), Medicaid represents a large share of state budgets and is a key part of the overall health care system.

This report highlights certain policies in place in state Medicaid programs in FY 2024 and policy changes implemented or planned for FY 2025, which began on July 1, 2024 for most states.1 The findings are drawn from the 24th annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA), in collaboration with the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD). States completed this survey in mid-summer of 2024, and 50 states responded to this year’s survey, although response rates for specific questions varied.2 The District of Columbia is counted as a state for the purposes of this report. Given differences in the financing structure of their programs, the U.S. territories were not included in this analysis.

Key Take-Aways

Provider Rates and Managed Care

- States had implemented (in FY 2024) and were planning (in FY 2025) a wide range of fee-for-service (FFS) rate increases across provider types and very few states were implementing rate restrictions. In FY 2024 and FY 2025, states reported inflation and workforce shortages were driving higher labor costs, resulting in pressure to increase provider rates across provider types. In FY 2024 and FY 2025, states continue to report rate increases for nursing facilities and home and community-based services (HCBS) providers more often than for other provider categories, reflecting ongoing staffing challenges for LTSS services. More than half of states reported rate increases for outpatient behavioral health providers (34 states), primary care providers (33 states), and dentists (28 states) in FY 2024, signaling a continued focus on leveraging rates to preserve or increase access in these areas. Beginning in 2026, the recently finalized Access rule requires states to conduct comparative rate analyses for certain services, publish fee schedules for all FFS rates, disclose payment rates for HCBS, and ensure HCBS payment adequacy (payment adequacy provision effective in 2030). A separate Managed Care rule also requires states to submit an annual managed care payment analysis for certain services (also effective in 2026).

- Many states reported increases in hospital FFS base rates and hospital supplemental payments in FY 2024 and FY 2025. State FFS payments to hospitals fall into two broad categories: (1) FFS base rates and (2) supplemental payments (typically made in a lump sum for a fixed period). Supplemental payments are often used to cover hospital costs that exceed the amounts covered by their FFS base rates. While managed care organizations (MCOs) have flexibility to determine provider payment methods and amounts, they often pay rates similar to FFS rates. Many states that contract with MCOs use “state directed payments” (SDPs) to make uniform rate increases that are like FFS supplemental payments. This year states were asked about changes to hospital FFS base rates, total (non-DSH) FFS hospital supplemental payments, and managed care state directed payments for hospital services.

- More than half of states (26 states) reported increasing both inpatient and outpatient hospital FFS base rates in FY 2024, and many states reported increases in both hospital FFS base rates and total non-DSH supplemental payments. States reported few decreases to hospital FFS payments (base rates or total supplemental payments).

- Thirty-seven of 41 responding states that contract with MCOs reported SDP(s) for hospital services in place as of July 1, 2024. Most of these states (26 of 37 states) reported that hospital SDPs, as a percentage of total Medicaid hospital reimbursement, were projected to increase in FY 2025 (compared to FY 2024). A few states commented on plans to significantly increase hospital SDPs in FY 2025, including increases up to the average commercial rate (the new payment rate ceiling established by federal rules that is substantially higher than the Medicare payment ceiling used for other Medicaid FFS supplemental payments).

- About two-thirds of responding MCO states (25 of 41) reported seeking CMS approval for a capitation rate amendment to address shifts in the average risk profile (or “acuity”) of MCO members in FY 2024 and/or FY 2025. States and plans faced another period of heightened rate setting uncertainty when the public health emergency (PHE) continuous enrollment period expired on March 31, 2023. States may use a variety of mechanisms (e.g., medical loss ratios (MLRs) with remittance requirements and/or risk corridors) to adjust plan risk to ensure payments are not too high or too low. However, even with these strategies in place, states may determine rate amendments are necessary, for example, if their actual experience differs significantly from the assumptions used for the initial certified rates. While many states and plans anticipated that enrollees likely to retain coverage during “unwinding” would have higher health care needs and utilization patterns (on average) than those disenrolled, states can seek rate amendments if projections do not match experience.

Benefits and Prescription Drugs

- Most states continue to implement benefit enhancements, particularly for mental health and/or substance use disorder (SUD) services. Consistent with trends in recent years, states reported expanding services across the behavioral health care continuum. In conjunction with the ongoing implementation of the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, there was a particular focus on enhancing crisis services in FY 2024 and FY 2025, including mobile crisis services and crisis services for youth. States also continue to invest in more coordinated and integrated physical and behavioral health care. In addition to behavioral health expansions, states reported enhanced pregnancy and postpartum services. Frequently reported benefit actions include coverage of doula services and other benefit additions or expansions aimed at reducing maternal morbidity and mortality and addressing racial/ethnic health disparities.

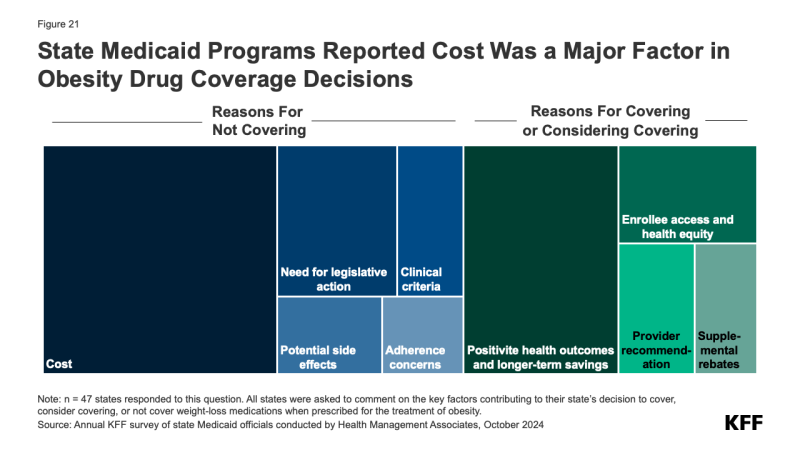

- Twelve state Medicaid programs reported covering GLP-1s (glucagon-like peptide-1s) when prescribed for the treatment of obesity, under FFS as of July 1, 2024. GLP-1 agonists have been used as a treatment for type 2 diabetes for over a decade and are covered by state Medicaid programs for that purpose. However, newer forms of these drugs, such as Wegovy and Zepbound, have gained widespread attention for their effectiveness as a treatment for obesity. While states must cover nearly all FDA-approved drugs for medically accepted indications, a long-standing statutory exception allows states to choose whether to cover weight-loss drugs under Medicaid, leading to variation in coverage policies across states. Recent KFF analysis found most large employer firms do not cover GLP-1 drugs for weight loss, coverage in ACA Marketplace plans remains limited, and coverage in Medicare is prohibited. A majority of state Medicaid programs reported that cost was a key factor contributing to their obesity drug coverage decisions, though half of states that currently do not cover the drugs noted they were considering or evaluating adding coverage. Rising prescription drug costs are an ongoing concern for states and nearly three-quarters of states reported at least one new or expanded initiative to contain prescription drug costs in FY 2024 or FY 2025. Efforts to implement or expand value-based arrangements (VBAs) with pharmaceutical manufacturers were the most frequently mentioned cost containment initiative across states.

Social Determinants of Health and Reducing Health Disparities

- A number of states are expanding or enhancing Medicaid coverage to help address enrollee social determinants of health (SDOH) or associated health-related social needs (HRSN). In 2022, CMS released a new framework for covering HRSN services under Section 1115 waivers, expanding flexibility for states to add certain short-term housing and nutrition supports as Medicaid benefits. Additional guidance and resources that identify allowable HRSN services and supports were released by CMS in late 2023. HRSN approvals to date include coverage of rent/temporary housing and utilities and meal support (up to three meals per day), departing from long-standing prohibitions on payment of “room and board” in Medicaid.

- States are implementing strategies to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities, including through changes in managed care contracts. Some state MCO contracts incorporate requirements to reduce health disparities. For example, states can require MCOs to have a health equity plan in place, conduct staff training on health equity and/or implicit bias, report racial disparities data, or incorporate enrollee feedback (among other requirements). The number of states with at least one specified MCO requirement related to reducing disparities grew to 37 states in FY 2025 (from 16 in FY 2022). States may also tie MCO financial quality incentives to reducing health disparities. About one-third of states reported at least one MCO financial incentive tied to reducing racial/ethnic disparities in place in FY 2024, most commonly linking capitation withholds or pay for performance incentives to improving health disparities.

Heading into FY 2025, state Medicaid officials were focused on continued efforts to address key priorities but noted state budget and administrative issues as challenges. In terms of policy priorities, states highlighted continued efforts to expand access to behavioral health services and LTSS (including addressing workforce shortages), implement payment and delivery system reforms, and advance key initiatives related to SDOH and transitions from incarceration (two policy areas also linked to reducing health disparities). Tackling these issues is often complex and involves sustained effort over multiple years. States also noted a number of ongoing and emerging challenges including rising health care costs (particularly for LTSS and prescription drugs); uncertain trajectory for state budgets and limited administrative capacity (due to outdated systems and state workforce shortages) at the same time administrative demands are increasing, especially tied to the implementation of new federal rules. The implementation of new federal rules could be further complicated by a Supreme Court ruling that could increase legal challenges to federal regulations. State officials also commented on challenges dealing with a lot of program uncertainty, adjusting to a new “normal” following the unwinding and expiration of pandemic-era policies, and the upcoming election that could have major implications for the program.

Acknowledgements

Pulling together this report is a substantial effort, and the final product represents contributions from many people. The combined analytic team from KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) would like to thank the state Medicaid directors and staff who participated in this effort. In a time of limited resources and challenging workloads, we truly appreciate the time and effort provided by these dedicated public servants to complete the survey and respond to our follow-up questions. Their work made this report possible. We also thank the leadership and staff at the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD) for their collaboration on this survey.

Introduction

Medicaid provides health insurance coverage to more than one in five Americans and accounts for nearly one-fifth of all U.S. health care expenditures. At the end of FY 2024 and heading into FY 2025, states were wrapping up the unwinding of the pandemic-related continuous enrollment provision and focused on addressing other key priorities including reducing long-standing health disparities (often exacerbated by the pandemic), improving access to behavioral health and long-term services and supports (LTSS), addressing enrollee social determinants of health, and implementing broader delivery system and value-based initiatives.

At the start of the pandemic, Congress enacted the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which included a requirement that Medicaid programs keep people continuously enrolled in Medicaid in exchange for enhanced federal funding. As a result, enrollment in Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) reached record highs, growing to 94 million enrollees, an increase of 23 million or 32% between February 2020 and April 2023. Medicaid enrollment growth along with enhanced subsidies in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplaces contributed to the lowest ever uninsured rate in 2022 and a stable uninsured rate in 2023.

The 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) ended the continuous enrollment provision on March, 31, 2023 and required states to begin the process of “unwinding” (i.e., resume historically typical eligibility redeterminations and disenroll individuals found to be no longer eligible for Medicaid). The CAA also phased down the enhanced federal matching funds through the end of 2023. Since the unwinding period began, millions of individuals have been disenrolled from Medicaid, but total net Medicaid and CHIP enrollment as of June 2024 remained over 8 million more than enrollment in February 2020, before the pandemic began. Though state unwinding timelines varied, all states except four completed unwinding renewals by August 2024.3 However, net enrollment trends remain uncertain and continue to evolve as states wrap up unwinding, re-enroll eligible individuals who may have lost coverage, process new applications, and, in some cases, expand eligibility.

This report draws upon findings from the 24th annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA), in collaboration with the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD). (Previous reports are archived here.) This year’s KFF/HMA Medicaid budget survey was conducted from June through September 2024 via a survey sent to each state Medicaid director in June 2024 followed by a set of focus groups with Medicaid officials in different roles (directors, deputy directors, chief financial officers, and medical directors) from various states. Overall, 50 states responded by October 2024,4 although response rates for specific questions varied. The District of Columbia is counted as a state for the purposes of this report. Given differences in the financing structure of their programs, the U.S. territories were not included in this analysis. The survey instrument is included as an appendix to this report.

This report examines Medicaid policies in place or implemented in FY 2024, policy changes implemented at the beginning of FY 2025, and policy changes for which a definite decision has been made to implement in FY 2025 (which began for most states on July 1, 20245 ). Policies adopted for the upcoming year are occasionally delayed or not implemented for reasons related to legal, fiscal, administrative, systems, or political considerations, or due to CMS approval delays. Key findings, along with state-by-state tables, are included in the following sections:

Delivery Systems

Context

Managed Care Models. For more than three decades, states have increased their reliance on managed care delivery systems with the aim of improving access to certain services, enhancing care coordination and management, and making future costs more predictable. Across the states, there is wide variation in the populations required to enroll in managed care, the services covered (or “carved in”), and the quality and performance incentives and penalties employed. Most states contract with risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs) that cover a comprehensive set of benefits (acute care services and sometimes long-term services and supports), but many also contract with limited benefit prepaid health plans (PHPs) that offer a narrow set of services such as dental care, non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT), or behavioral health services. A minority of states operate primary care case management (PCCM) programs which retain fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursements to providers but link beneficiaries with a primary care provider who is paid a small monthly fee to provide case management services in addition to primary care. While the shift to MCOs has increased budget predictability for states, the evidence about the impact of managed care on access to care and costs is both limited and mixed.6 ,7 ,8 Recently finalized regulations, addressing Medicaid managed care access, finance, and quality, are primarily aimed at strengthening standards for timely access to care and states’ monitoring and enforcement efforts.

Capitation Rates and Risk Mitigation. MCOs are at financial risk for services covered under their contracts, receiving a per member per month “capitation” payment for these services. Capitation rates must be actuarially sound9 and are applied prospectively, typically for a 12-month rating period, regardless of changes in health care costs or utilization.10 States may use a variety of risk mitigation tools to ensure payments are not too high or too low, including risk sharing arrangements, risk and acuity adjustments, medical loss ratios (MLR), or incentive and withhold arrangements. When, however, significant enrollment, utilization, cost, and acuity changes began to emerge early in the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE), CMS allowed states to modify managed care contracts, and many states implemented COVID-19 related “risk corridors” (where states and health plans agree to share profit or losses), allowing for the recoupment of funds. In last year’s survey, nearly two-thirds of responding MCO states reported implementing a pandemic-related MCO risk corridor (in 2020, 2021, and/or 2022), leading to the recoupment of payments for many states. States and plans faced another period of heightened rate setting uncertainty when the PHE continuous enrollment period expired on March 31, 2023.

Addressing Health Disparities. In the United States, racial and ethnic health disparities persist, driven by inequitable health care access and utilization and by social and economic factors, often referred to as social determinants of health (SDOH), that are rooted in historic and ongoing racism and discrimination. Like the federal government, many states have identified addressing health disparities as a key Medicaid priority and are leveraging their MCO contracts to reduce health disparities, for example, by addressing SDOH and tying MCO financial quality incentives (e.g., performance bonuses or withholds) to health disparity reductions.

This section provides information about:

- Managed care models

- MCO medical loss ratio (MLR) and remittance requirements

- MCO capitation rate amendments

- SDOH MCO contract requirements

- Strategies to reduce health disparities

Findings

Managed Care models

Capitated managed care remains the predominant delivery system for Medicaid in most states. As of July 1, 2024, all states except five – Alaska, Connecticut,11 Maine, Vermont,12 and Wyoming – had some form of managed care (MCOs and/or PCCM) in place (Figure 2). As of July 1, 2024, 42 states13 were contracting with MCOs, up from 41 states in 2023 (with the addition of Oklahoma); only two of these states (Colorado and Nevada) did not offer MCOs statewide (although Nevada plans to expand MCOs statewide in 2026). Twelve states reported operating a PCCM program, one fewer than reported in 2023 (as North Dakota ended its PCCM program in December 2023).14

Of the 46 states that operate some form of comprehensive managed care (MCOs and/or PCCM), 34 states operate MCOs only, four states operate PCCM programs only, and eight states operate both MCOs and a PCCM program. In total, 30 states15 were contracting with one or more limited benefit prepaid health plans (PHPs) to provide Medicaid benefits including behavioral health care, dental care, vision care, non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT), or long-term services and supports (LTSS).

Capitation Rates and Risk Mitigation

Minimum Medical Loss Ratios (MLRs) and Remittance Requirements

The medical loss ratio (MLR) reflects the proportion of total capitation payments received by an MCO spent on clinical services and quality improvement, where the remainder goes to administrative costs and profits. To limit the amount that plans can spend on administration and keep as profit, CMS published a final rule in 2016 that requires states to develop capitation rates for Medicaid to achieve an MLR of at least 85% in the rate year.16 There is no federal requirement for Medicaid plans to pay remittances to the state if they fail to meet the MLR standard, but states have discretion to require remittances. The 2024 Consolidated Appropriations Act included a financial incentive to encourage certain states to collect remittances from Medicaid MCOs that do not meet minimum MLR requirements. The Biden-Harris Administration’s FY 2024 and 2025 budgets went further proposing to require Medicaid managed care plans to meet an 85% minimum MLR and to require states to collect remittances if plans fail to meet the minimum MLR. An analysis of National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) data for the Medicaid managed care market shows the average loss ratios (in aggregate across plans) increased slightly in 2023 compared to 2022 (from 86% to 87%), implying a potential decrease in profitability, but remained lower than in 2018 and 2019. This year’s survey asked states whether they have a state required minimum MLR and whether they require MCOs that do not meet the minimum MLR requirement to pay remittances.

Nearly all MCO responding states (38 of 41) reported a minimum MLR requirement is always in place for MCOs as of July 1, 2024 (Figure 3). While states must use plan-reported MLR data to set future payment rates so that plans will “reasonably achieve” an MLR of at least 85%, states are not required to set a minimum MLR for their managed care plans. If states set a minimum MLR requirement, it must be at least 85%.17 While most states that described their requirements reported a minimum MLR requirement of 85%, several states reported higher requirements that ranged from 86% to 91%. A few states noted that minimum MLRs may vary by program. For example, in Pennsylvania, the minimum MLR requirement is set at 85% for MCOs covering acute care only (hospital and physician services) and at 90% for MCOs that cover acute care and LTSS.

More than three-quarters of responding MCO states report they always require remittance payments when an MCO does not meet minimum MLR requirements (Figure 4). Thirty-four states reported that they always require MCOs to pay remittances, while two states indicated they sometimes require MCOs to pay remittances. States reporting that they sometimes require remittances may limit this requirement to certain MCO contracts. For example, Rhode Island reported that the remittance requirement did not apply to all populations. Additionally, some states (North Carolina, Oregon, and Tennessee) give MCOs that fail to meet the state required minimum MLR the option to either remit funds to the state and/or use funds towards community reinvestments (see MCO Contract Requirements Related to Social Determinants of Health below for more information). Five states do not require remittances (including two states that do not set a minimum MLR requirement). States that do not have minimum MLR and remittance requirements in place may have other risk mitigation strategies such as profit caps or experience rebates and/or risk corridors.

Rate Amendments

State Medicaid programs use the most recent and accurate enrollment, cost, and utilization data available to ensure that MCO capitation rates are actuarially sound and that MCOs are not over-paid or under-paid for the services they deliver. Even if risk mitigation strategies are in place (e.g., MLR with remittance and/or risk corridors), states may determine rate amendments are necessary, for example, if their actual unwinding experience differs significantly from the assumptions used for the initial certified rates. Prior to the start of unwinding, plans expected the overall risk profile of their members to increase, with “stayers” likely to be sicker than “leavers.”

During a contract rating period, states may increase or decrease rates by 1.5% per rate cell (which apply to population subgroups with one or more common characteristics such as age, gender, eligibility category, and geographic region) without seeking CMS approval for the change (different rules apply for states with approved rate ranges per cell).18 To make a larger change, states must submit a rate amendment for federal approval that addresses and accounts for all differences from the most recently certified rates. This year’s survey asked states whether they have or will seek CMS approval for a capitation rate amendment to address “acuity shifts” (i.e., shifts in the average risk profile and utilization patterns) among MCO enrollment due to the unwinding in the rating period that began in FY 2024 and the rating period that begins in FY 2025.

About two-thirds of responding MCO states (25 of 41) reported seeking CMS approval for a capitation rate amendment to address acuity shifts among MCO enrollment due to the unwinding for a rating period beginning in FY 2024 and/or FY 2025 (Figure 5). An additional four states reported that while they did not seek a rate amendment to address acuity shifts for the rating period that began in FY 2024, whether they seek a rate amendment for the rating period that begins in FY 2025 is undetermined. Twelve states have not and do not plan to seek a rate amendment to address acuity shifts due to the unwinding in either rating period.

MCO Requirements Related to Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. Addressing social determinants of health is important for improving health outcomes and reducing health disparities. While there are limits, states can use Medicaid – which, by design, serves a primarily low-income population with greater social needs – to address social determinants of health. This year’s survey asked states about MCO contract requirements related to social determinants of health in place in FY 2024 or planned for implementation in FY 2025.

Nearly all responding MCO states (39 of 40) reported leveraging Medicaid MCO contracts to promote at least one strategy to address social determinants of health in FY 2024 (Figure 6). In FY 2024, more than three-quarters of responding MCO states reported requiring MCOs to screen enrollees for behavioral health needs, screen enrollees for social needs, provide referrals to social services, and partner with community-based organizations (CBOs). Similar numbers of states (about half) reported requiring MCOs to encourage/or require providers to capture SDOH data using ICD-10 Z codes, incorporate uniform SDOH questions within screening tools, employ community health workers (CHWs),19 and track the outcomes of referrals to social services. Fewer states reported requiring MCO community reinvestment (i.e., directing plans to reinvest a portion of revenue or profits into the communities they serve) compared to other strategies; however, a few states reported plans to require these activities in FY 2025.

While most states with community reinvestment requirements reported requiring MCOs to reinvest a percentage of their revenue or profits, a few states tie reinvestment requirements to state minimum MLRs and allow or encourage MCOs that do not meet the required MLR to reinvest all or a portion of the remittance payment.

State examples of community reinvestment requirements include:

- In Arizona, MCOs are required to reinvest 6% of their profits into the community for each Medicaid line of business. Community reinvestment activities must support health-related social needs (HRSN) and demonstrate evidence-based measurable impacts to health outcomes. MCOs must submit an annual community reinvestment plan, which outlines their plans for the use of reinvestment funds for the year, as well as a community reinvestment report, which provides an overview of the measurable impacts of each activity (quantitative or qualitative) and the HRSN domain impacted (e.g., food insecurity, housing, transportation, etc.).

- New Mexico requires each MCO to contribute a portion of their after-tax underwriting gain to community reinvestments and to submit an annual community reinvestment plan to the state for review and approval that details the MCO’s community reinvestment strategies, activities, and the anticipated time frame for demonstrable impact. The MCO’s strategies must include efforts to collaborate with other MCOs to attain collective impact on the areas of focus identified by the state including efforts to develop, expand, and retain in-state behavioral health residential providers to reduce the unnecessary utilization of inpatient, emergency room, and out-of-state services.

- In North Carolina, MCOs may voluntarily contribute to health-related resources that help address members’ and communities’ unmet health-related needs. MCOs that do not meet the state required MLR have the option to make contributions to health-related resources in lieu of all or a portion of the remittance owed to the state. MCOs must submit proposals that align with the state’s quality strategy for review and approval by the state.

- In Tennessee, if an MCO achieves a medical loss ratio of less than 85%, the MCO must either remit funds to the state and/or propose a reinvestment plan. An MCO that doesn’t meet the minimum MLR requirement and opts for reinvestment must submit a community reinvestment plan to the state for approval.

Financial Incentives Tied to Reducing Health Disparities

States use an array of financial incentives to improve quality, including linking performance bonuses or penalties, capitation withholds, or value-based state-directed payments to quality measures. States implement financial incentives across delivery systems (fee-for-service and managed care). This year’s survey asked states if they had an MCO financial quality incentive (e.g., a performance bonus or penalty, capitation withhold) that rewards quantitative improvement in racial/ethnic disparities for one on more populations in place in FY 2024 or planned for FY 2025 or beyond.

About one-third of responding MCO states (13 of 40) reported at least one MCO financial incentive tied to reducing racial/ethnic disparities in place in FY 2024 (Figure 7). Six additional states reported plans to implement MCO financial incentives in FY 2025 or later. States most commonly reported linking (or planning to link) capitation withholds or pay for performance incentives to improving health disparities. At least five states (Colorado, Louisiana, Missouri, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania) specifically mentioned current or planned MCO financial incentives focused on reducing disparities in maternal and child health. Other notable state examples include:

- Kentucky’s MCO capitation withhold is tied to performance improvement on six core measures, including a social need screening and intervention measure (HEDIS SNS-E). MCOs are incentivized to address disparities by screening enrollees for unmet food, housing, and transportation needs and closing identified gaps.

- In Louisiana, one-quarter of the capitation withhold is attributed to health equity performance improvement efforts, including development and maintenance of a Health Equity Plan and reporting and reduction of disparities in select maternal health, child health, preventive, and behavioral health measures.

- In Massachusetts, the Quality and Equity Incentive Programs incentivize accountable care organizations (ACOs), MCOs, and the MA Behavioral Health Vendor to pursue performance improvements in three domains: demographic and health-related social needs data, equitable quality and access, and capacity and collaboration.

Other MCO Requirements Related to Reducing Disparities

In addition to implementing financial incentives tied to improvements in health disparities, states can leverage managed care contracts in other ways to promote reducing health disparities. For example, states can require MCOs to achieve national standards for advancing health equity, conduct staff training on health equity and/or implicit bias, develop new positions related to health equity, report racial disparities data, incorporate enrollee feedback, among other requirements. In this year’s survey, states that contract with MCOs were asked about whether certain MCO contract requirements related to reducing disparities were in place in FY 2024 or planned for implementation in FY 2025.

Nearly all responding MCO states (35 of 40) reported at least one specified MCO requirement related to reducing disparities in place in FY 2024 (Figure 8). In FY 2024, about two-thirds of states reported requiring MCOs to have a health equity plan in place (27 states) and train staff on health equity and/or implicit bias (27 states). Over half of states reported requiring MCOs to meet health equity reporting requirements (24 states) and seek enrollee input or feedback to inform health equity initiatives (22 states). Fewer states reported requiring MCOs to achieve NCQA’s Health Equity Accreditation (previously the Multicultural Health Care Distinction) (15 states) or have a health equity officer (13 states). Among states with at least one requirement in place in FY 2024, three-quarters (27 of 35) reported three or more specified requirements in place (data not shown). The number of MCO states with at least one specified MCO requirement related to reducing disparities grew significantly from 16 states in FY 2022 and is expected to grow to 37 states in FY 2025.

Provider Rates And Taxes

Context

States have substantial flexibility to establish Medicaid provider reimbursement methodologies and amounts, especially within a fee-for-service (FFS) delivery system where a state Medicaid agency pays providers or groups of providers directly. While states with capitated managed care arrangements are generally not permitted to direct how their contracted managed care organizations (MCOs) pay providers, state determined FFS rates remain important benchmarks for MCO payments in most states. To improve access to Medicaid services across both FFS and managed care delivery systems, recently finalized rules include provisions that require states to improve payment rate transparency and promote payment adequacy for some direct care workers (see Box 1).

Fee-for-Service Rates. While federal law and regulations grant states broad latitude to determine FFS provider payments, they also require that payments be sufficient to ensure that Medicaid enrollees have access to care that is equal to the level of access enjoyed by the general population in the same geographic area.20 CMS reviews and approves state changes to FFS payment methodologies through the Medicaid State Plan Amendment process.21 In addition to FFS provider payments, states are permitted to make multiple types of “supplemental” payments. States make these payments for a variety of purposes including to supplement Medicaid “base” FFS payment rates that often do not fully cover provider costs as well as to help support the costs of care for uninsured patients.

Managed Care Provider Rates. States pay Medicaid MCOs a set per member per month (“capitation”) payment for the Medicaid services specified in their contracts. Under federal law, payments to Medicaid MCOs must be actuarially sound. Actuarial soundness means that “the capitation rates are projected to provide for all reasonable, appropriate, and attainable costs that are required under the terms of the contract and for the operation of the managed care plan for the time period and the population covered under the terms of the contract.” Plan rates are usually set for a 12-month rating period and must be reviewed and approved by CMS each year. States are generally prohibited from contractually directing how a managed care plan pays its providers.22 Subject to CMS approval, however, states may implement certain “state directed payments” (SDPs)23 that require managed care plans to adopt minimum or maximum provider payment fee schedules, provide uniform dollar or percentage increases to network providers (above base payment rates), or implement value-based provider payment arrangements.

Box 1: Federal Rules Finalized in 2024

FFS / Access Rule. The recently finalized Ensuring Access to Medicaid Services final rule (Access rule)24 is designed to promote quality of care and improved health outcomes by advancing access to care for Medicaid enrollees. The rule addresses several dimensions of access: increasing provider rate transparency and accountability, standardizing data and monitoring, and creating opportunities for states to promote active enrollee engagement in their Medicaid programs. The rule requires states, in part, to:

- Conduct comparative rate analyses. States must compare their FFS payment rates for primary care, obstetrical and gynecological care, and outpatient mental health and substance use disorder services to Medicare rates, and publish the analysis every two years, with the first analysis published by July 1, 2026.

- Publish fee schedules. By July 1, 2026, states must publish all FFS rates on a publicly available and accessible website and make updates within one month of a payment rate change.

- Disclose payment rates for HCBS. By July 1, 2026, states must publish the average hourly rate paid for personal care, home health aide, homemaker, and habilitation services, and publish the disclosure every two years.

- Establish a direct care worker payment advisory group. Within two years (of effective date of the final rule), states must establish an advisory group that includes direct care workers, beneficiaries, beneficiaries’ authorized representatives, and other interested parties to advise and consult on the sufficiency of payment rates (at least every two years) for personal care, homemaker, home health aide, and habilitation services.

- Ensure HCBS payment adequacy. Beginning in July 2030, states must ensure a minimum of 80% of Medicaid payments for homemaker, home health aide, and personal care services are spent on compensation for direct cares workers, as opposed to administrative overhead or profit (known as the “80/20 rule.”)

LTC Facility Staffing Rule. One provision of the recently finalized Minimum Staffing Standards for Long-Term Care Facilities and Medicaid Institutional Payment Transparency Reporting final rule (LTC Facility Staffing rule) requires states, beginning in June 2028, to collect and report on the percent of Medicaid payments that are spent on compensation for direct care workers and support staff delivering care in nursing facilities and intermediate care facilities, for individuals with intellectual disabilities.25

Managed Care Rule. The recently finalized Medicaid and CHIP Managed Care Access, Finance, and Quality final rule (Managed Care rule) introduced a managed care payment analysis requirement and made several changes to state directed payment requirements including:

- Requiring states to submit annual payment analysis. States must submit an annual analysis comparing managed care plans’ payment rates for certain services to Medicare rates and compare certain HCBS rates to state FFS payment rates (beginning the first rating period that begins on or after July 9, 2026.)26

- Eliminating the requirement to obtain prior approval for certain SDPs. States will no longer be required to seek prior CMS approval for SDPs that impose minimum fee schedules set at the Medicare payment rate.27

- Establishing SDP payment rate ceiling for certain providers. The rule allows SDPs for inpatient and outpatient hospital services, nursing facility services, and the professional services at an academic medical center to reach “average commercial rates”28 (which is substantially higher than the Medicare payment ceiling used for many FFS supplemental payments).29

Provider Rate Implications of Economic and Fiscal Conditions. Historically, FFS provider rate changes generally reflect broader economic conditions. During economic downturns when states may face revenue shortfalls, states have typically turned to provider rate restrictions to contain costs. Conversely, states are more likely to increase provider rates during periods of recovery and revenue growth. During the COVID-19 public health emergency, however, states were able to generally avoid rate cuts due to temporary federal support from the pandemic-related enhanced Medicaid matching funds as well as enhanced funding for home and community-based services (HCBS). In FY 2024 and FY 2025, states reported inflation and workforce shortages were driving higher labor costs, resulting in pressure to increase provider rates.

Provider Taxes. States have considerable flexibility in determining how to finance the non-federal share of state Medicaid payments, within certain limits. In addition to state general funds appropriated directly to the Medicaid program, most states also rely on funding from health care providers and local governments generated through provider taxes, user fees, intergovernmental transfers (IGTs), and certified public expenditures (CPEs). Over time, states have increased their reliance on provider taxes, with expansions often driven by economic downturns. Federal regulations30 require provider taxes to be broad-based (imposed on all non-governmental entities, items, and services within a class), and uniform (consistent in amount and scope across the entities, items, or services to which it applies), and must not hold taxpayers harmless (i.e., directly or indirectly guarantee that the provider will be repaid for all or a portion of the tax). Also, a provider tax will meet the hold harmless “safe harbor threshold” if it generates revenue that does not exceed 6% of net patient revenue.

This section provides information about:

- Hospital reimbursement

- Nursing facility reimbursement

- FFS reimbursement rates for other provider types

- Payment rate transparency

- Provider taxes

Findings

Hospital Reimbursement – FFS Base Rates, Supplemental Payments, and State Directed Payments (SDPs)

States make different types of Medicaid payments to hospitals. The two broad categories of FFS payment are (1) FFS base rates and (2) supplemental payments, typically made in a lump sum for a fixed period of time. States use supplemental payments, including upper payment limit (UPL), disproportionate share hospital (DSH), or uncompensated care pool payments, to cover hospital costs that exceed the amounts covered by their FFS base rates. DSH payments can also be used to pay for unpaid costs of care for the uninsured. The Medicaid statute31 requires states to make Medicaid DSH payments to hospitals, and most states also make other types of FFS supplemental payments, although payment amounts and how they are distributed to hospitals vary considerably across states. Because many types of supplemental payments are interchangeable, an increase in one type can lead to a decrease in another. Increases or decreases in base FFS payments may also result in supplemental payment changes.

Hospital FFS base rates (and payment methods) also vary considerably across states and, on average, are below hospitals’ costs of providing services to Medicaid enrollees and below Medicare payment rates for comparable services,32 causing some states to rely more heavily on supplemental payments than others to help cover hospitals’ costs. Within a state, reimbursement methodologies and levels may also vary by hospital type (e.g., community, critical access, and academic medical center hospitals). While managed care organizations have flexibility to determine provider payment methodologies and amounts, they often pay rates that are similar to FFS rates. As a result, many states that contract with MCOs use state directed payments (SDPs) to make uniform rate increases that are like FFS supplemental payments.33

According to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), in FY 2022, 61% of Medicaid payments to hospitals were made through managed care delivery systems and 39% were made on a FFS basis. Further, about half of FFS payments to hospitals were made through supplemental payments, while one-third of managed care payments to hospitals are made through SDPs.

In this year’s survey, states were asked to report on changes made to their FFS base rates, non-DSH supplemental payments, and hospital SDPs in FY 2024 and changes planned for FY 2025. DSH was excluded as individual state DSH allotments are federally determined and MACPAC is statutorily required to annually report on Medicaid DSH allotments.

Hospital FFS Base Rates & Non-DSH FFS Supplemental Payments

Overall, few responding states reported hospital rate decreases (FFS base rates or supplemental payments) in FY 2024 or FY 2025 (Table 1). Among the states that reported decreases, several reported that the decreases (to FFS base rates or non-DSH supplemental payments) offset increases in other areas. For example, two states (California and Oklahoma) reported transitions in utilization from FFS to managed care caused non-DSH supplemental payments to decrease while managed care state directed payments increased (in FY 2024 and/or FY 2025.) Michigan reported its reduction in total non-DSH supplemental payments (in FY 2024) offset an increase in FFS base rates for hospitals designated as Level I or Level II Trauma Centers. Massachusetts reported while hospital base rates were set to decrease in FY 2025, overall payments to hospitals would increase when add-on and incentive payments are included. In contrast, Utah reported plans to reduce a small graduate medical education (GME) supplemental payment in FY 2025 without noting any offsetting FFS base rate increases.

More than half of responding states (26 states) reported increasing both inpatient and outpatient hospital FFS base rates in FY 2024 (Table 1). Nearly half (20 states) reported plans to increase inpatient and outpatient FFS base rates in FY 2025. A few states commented on more significant FFS hospital base rate increases:

- Illinois reported a 10% across the board increase for both inpatient and outpatient base rates in FY 2024.

- Maine reported substantial increases to inpatient DRG (diagnosis-related group) rates in FY 2025 to align more closely with Medicare rates and increased outpatient rates in both FY 2024 and FY 2025, benchmarking them to Medicare outpatient rates.

- Missouri reported an average 9% increase in FFS hospital per diems in FY 2025 due to increased cost trends.

Many states reported increases in both hospital base rates and non-DSH supplemental payments in both FY 2024 and FY 2025 (Figure 9). Most responding states reported making non-DSH supplemental payments for both inpatient (42 of 48 in both years) and outpatient (37 of 48 in FY 2024 and 36 of 47 in FY 2025) hospital services (Table 1). Of the 42 states with inpatient supplemental payments, nearly half in FY 2024 (18 states) and one-third in FY 2025 (14 states) planned to increase both FFS base rates and supplemental payments (Figure 9). Of the states reporting outpatient supplemental payments (37 in FY 2024 and 36 in FY 2025), over one-third in FY 2024 (13 states) and about one-quarter in FY 2025 (9 states) planned to increase both FFS base rates and supplemental payments.

Hospital State Directed Payments

Recent reports indicate state directed payments have been a major driver of Medicaid expenditure growth in recent years. New Medicaid managed care rules finalized in 2024 permit states to pay hospitals and nursing facilities at the average commercial payment rate (ACR) when using directed payments, which is substantially higher than the Medicare payment ceiling used for other Medicaid FFS supplemental payments. Recently revised CBO Medicaid spending projections for 2025-2034 reflect a 4% (or $267 billion) increase with half of the increase attributed to expected growth in directed payments in Medicaid managed care (driven in part by the rule change allowing states to pay at the ACR).

Thirty-seven34 of 41 responding states that contract with MCOs reported an SDP for hospital services (excluding SDPs requiring a FFS payment floor) in place as of July 1, 2024. Only four states that contract with MCOs reported no SDPs in place (Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, and North Dakota). States reporting a hospital SDP in place were also asked about whether the projected size of their hospital SDP(s) as a percentage of total Medicaid hospital reimbursement (under FFS and managed care arrangements) was expected to increase, decrease, or stay about the same in FY 2025 compared to FY 2024. The vast majority of MCO states (26 of 37) reported that the hospital SDP payments, as a percentage of total Medicaid hospital reimbursement, were projected to increase in FY 2025 (Figure 10 and Table 1). A few states commented on significantly increasing, or plans to significantly increase, hospital SDPs in FY 2024 or 2025, including increases up to the ACR ceiling:

- The District of Columbia reported seeking CMS approval to increase hospital inpatient and outpatient SDPs up to the ACR ceiling effective in FY 2025.

- Michigan increased its inpatient hospital SDP by $2.5 billion in FY 2024 (113.64%), with $1.8 billion coming from federal funds.

- Nebraska is implementing a new hospital SDP in FY 2025 expected to generate approximately $1 billion in federal funds per year.35

- Utah reported having SDPs in place targeting 95% of ACR for private hospitals and 100% of ACR for state-owned hospitals in FY 2025.

Nursing Facility Reimbursement – FFS Base Rates and Supplemental Payments

State Medicaid programs typically pay nursing facilities a daily “per diem” rate that is determined by state-specific methodologies that are often cost-based and commonly account for several specified cost categories such as direct care costs (including nursing and other direct care worker wages and benefits), indirect care costs (ancillary costs such as social services, patient activities, medical directorship, and clinical consultants), administration (such as administrative services, food service, housekeeping, maintenance, laundry, and utilities), and capital costs for the physical building.36 Most states also adjust base rates by patient acuity and may also choose to make quality incentive payments and supplemental payments intended to make up the difference between base FFS payments and the amount that Medicare would have paid for the same service. To address workforce shortages in nursing facilities, the recently finalized LTC Facility Staffing rule creates new minimum staffing requirements for nursing facilities with implications for Medicaid nursing facility reimbursement policies and budgets.

Overall, few responding states (5) reported nursing facility rate decreases (FFS base rates or supplemental payments) in FY 2024 or FY 2025 (Table 2). One of these states (California) attributed its decrease in total nursing facility supplemental payments to utilization shifts from FFS to managed care. Another state (Indiana) reporting a decrease in total nursing facility supplemental payments is implementing an LTSS managed care program in FY 2025.

Most responding states reported increasing nursing facility FFS base rates in both FY 2024 (45 of 49) and FY 2025 (39 of 49) (Table 2). Reflecting the ongoing staffing challenges impacting nursing facility services, several states reported more significant nursing facility base rate increases. Examples include:

- Iowa reported a 25.49% base rate increase in FY 2024.

- Montana increased base rates by 8.24% effective July 1, 2024.

- Nevada reported increased base, pediatric, and ventilator rates by 24.5% in FY 2024.

- Ohio reported a 17% increase in FY 2024.

- Rhode Island reported completing a rate review which will result in a 14.5% increase to the direct care, indirect care, and other direct care components of the nursing facility base rates as of October 1, 2024.

- Texas reported increasing rates by 8-14% across the various Resource Utilization Groups effective September 1, 2023.

Many states reported increasing both nursing facility FFS base rates and total nursing facility supplemental payments in both FY 2024 and FY 2025 (Figure 11). About two-thirds of responding states (33 of 49) made supplemental payments for nursing facility services for both FY 2024 and FY 2025 (Table 2). Of these 33 states, nearly half (16 states) in FY 2024 and over one-third (12 states) in FY 2025 planned to increase both FFS base rates and supplemental payments.

FFS Reimbursement Rates for Other Provider Types

In addition to nursing facility and hospital rates, this year’s survey asked states to report FFS rate changes in FY 2024 and FY 2025 for the following provider types: primary care providers, OB/GYNs, outpatient behavioral health (BH) clinicians, home health, dentists, lay professionals, home and community-based services (HCBS) providers, and providers of non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT).

At the time of the survey, responding states had implemented or were planning more FFS rate increases than rate restrictions in both FY 2024 and FY 2025 (Figure 12 and Table 3).37 ,38 Forty-eight states in FY 2024 and 44 states in FY 2025 reported implementing FFS rate increases for at least one (non-hospital, non-nursing facility) provider category. Only one state in FY 2024 and three in FY 2025 implemented or were planning to implement at least one rate restriction.

States reported rate increases for HCBS providers more often than for other provider categories (Figure 12). Between April 1, 2021 and March 31, 2022, states received an additional 10 percent in federal matching funds for HCBS spending, funded through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). States were required to reinvest the additional federal funding in Medicaid HCBS, resulting in an estimated $37 billion of new HCBS funding. As of the end of 2023, the largest use of funds was for workforce recruitment and retention, often through payment rate increases or retention bonuses for HCBS workers. The ARPA funding will end in most states by March 2025 (though some states have received extensions into 2026). In this year’s survey, most states reported increasing HCBS rates in both FY 2024 (39 states) and FY 2025 (32 states). One state (Wyoming) commented that it planned to continue enhanced ARPA-funded rates in both FY 2024 and FY 2025 and was also planning to seek permanent funding from its legislature to continue the enhanced rates beyond the expiration of ARPA HCBS funding. Examples of other HCBS rate increases reported include the following:

- California and the District of Columbia reported HCBS rate increases in both FY 2024 and FY 2025 to account for increases in California’s statewide minimum wage and the District of Columbia’s living wage. Over 6,000 California HCBS providers also received retention payments in FY 2024.

- Connecticut enacted several HCBS rate increases including a 12.5% increase to home-delivered meals and 8.6% increase to adult day services for individuals enrolled in the State’s 1915(i) waiver.

- Kentucky implemented a legislatively mandated 10% rate increase for HCBS providers in FY 2024 and will study HCBS rates in FY 2025.

- Mississippi increased all HCBS rates by 4% in FY 2024.

- Texas enacted legislation in 2023 to increase personal care attendant rates in FY 2024 from $8.11 to $10.60, a 30% increase.

Thirty-three states reported increasing primary care provider rates in FY 2024 and 20 states reported plans to do so in FY 2025. States reporting notable primary care rate increases for FY 2024 or FY 2025 include Kansas (9% in FY 2025), Michigan (7.5% in FY 2024), Ohio (6% in FY 2024), and South Dakota (5% in FY 2024). Other states reported benchmarking to Medicare rates, for example, 87.5% of Medicare in California and 70% of Medicare (if rates were lower) in Illinois.

This year’s survey found a continued focus on improving dental rates with 28 states implementing a dental rate increase in FY 2024. Sixteen states also reported planned increases to dental rates in FY 2025. States reporting notable dental rate increases for FY 2024 or FY 2025 include Ohio (93% increase on average per procedure in FY 2024), Wyoming (25% increase in FY 2025), Nebraska (12.5% increase in FY 2025), Vermont (raising rates to 75% of regional commercial rates in FY 2024), and Missouri (increases in FY 2025 to cover a larger percentage of usual and customary rates).

Thirty-four states implemented FFS rate increases for one or more outpatient behavioral health providers in FY 2024 and 26 states plan to do so in FY 2025. Examples of outpatient providers include licensed psychiatrists, psychologists, clinical social workers, mental health counselors, and marriage and family therapists. Examples of rate increases reported for FY 2024 or FY 2025 include:

- Mississippi will increase behavioral health codes by 15% over the course of FY 2024 and FY 2025 for those services billed using the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes.

- Montana conducted a BH provider reimbursement rate study, resulting in rate increases (which vary by service) in FY 2024 and FY 2025, bringing rates closer to identified benchmarks.

- New Mexico increased behavioral health service rates to a minimum of 120% of the 2023 Medicare fee schedule in FY 2024.

- South Dakota increased rates for Community Mental Health Centers (CMHCs) and substance use disorder (SUD) services by 16% in FY 2024.

- Washington increased developmental screening codes by 100% and implemented varied rate increases for mental and behavioral health services ranging from 7% to 22% in FY 2024.

In FY 2024, 27 states that reimburse services provided by lay professionals on a FFS basis implemented rate increases for one or more lay professionals and 15 states plan to do so in FY 2025. Lay health care professionals, such as doulas, community health workers (CHWs), lay midwives, and peer support specialists, are frontline health workers with a deep understanding of the communities they serve. Typically, they have received some training and may be certified in some cases but are not licensed clinicians. Many state Medicaid programs have chosen to reimburse services provided by one or more types of lay professionals to help reduce health disparities, support other health care providers, and improve health outcomes. Many states reporting rate increases for lay professionals did not specify the type of lay professional impacted by the increase(s), but those that did frequently identified doulas and CHWs. A number of states noted the recent addition of doula coverage including the District of Columbia, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Washington.

In FY 2024, 21 states that set FFS NEMT rates implemented FFS rate increases and 15 states plan to do so in FY 2025. State Medicaid programs are required to provide non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) for enrollees who have no other means of transportation to access medically necessary health care services. NEMT is provided in several ways. States may reimburse transportation providers directly on a FFS basis, outsource the service on a FFS or capitated basis to a “transportation broker” (which could be a private vendor or a local or county governmental entity); or carve the benefit into an MCO contract.39 Two states reported particularly notable FFS rate increases: Illinois reported an average statewide increase of 40% for NEMT rates in FY 2024 and Ohio implemented a 79% increase for certain NEMT services that are not county-administered.

Payment Rate Transparency

The recently finalized Access rule rescinds regulations that previously required states to produce and submit to CMS at least once every three years Access Monitoring Review Plans (AMRPs) that analyzed the sufficiency of access to care. Instead, the Access Rule has replaced the AMRP requirement with a more streamlined and standardized process that in part requires states to compare FFS payment rates for rates for primary care, OB/GYN, and outpatient mental health and substance use disorder (SUD) services to Medicare rates at least every two years, with the first analysis published by July 1, 2026. The recently finalized Managed Care rule requires a similar payment analysis annually. This year’s survey asked states whether they have conducted comparative rate analyses of FFS Medicaid payment rates within the last two years.

FFS Analysis

More than one-third of responding states (19 of 50) reported conducting a comparative rate analysis of FFS Medicaid payment rates that included primary care, OB/GYN, and outpatient MH/SUD services within the last two years (Figure 13). An additional eleven states reported conducting an analysis including one or two of the required provider types, while 20 states reported that they had not conducted an analysis of any of the three required provider types. Of the 30 states that had conducted a FFS comparative rate analysis (for at least one “required” provider type), over half benchmarked their FFS rates to Medicare rates. Several states reported benchmarking to a combination of Medicare and another benchmark (e.g., commercial rates and/or other states’ FFS rates). Many states also reported including other physician specialists and dental providers in their analyses. In addition to the various benchmarks used, there may be other methods states used for their comparative rate analyses that differ from those required in the final Access rule.

Provider Taxes

States continue to rely on provider taxes and fees to fund a portion of the non-federal share of Medicaid costs. Provider taxes are an integral source of Medicaid financing, comprising approximately 17% of the non-federal share of total Medicaid payments in FY 2018 according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO).40 At the beginning of FY 2003, 21 states had at least one provider tax in place. By FY 2013, all but one state (Alaska) had at least one provider tax or fee in place. In this year’s survey, states reported a continued reliance on provider taxes and fees to fund a portion of the non-federal share of Medicaid costs. In FY 2024, 39 states had three or more provider taxes in place, eight states had two provider taxes in place, and three states had one provider tax in place (Figure 14).41 As of July 1, 2024, 38 responding states reported at least one provider tax that is above 5.5% of net patient revenues, which is close to the maximum federal safe harbor or allowable threshold of 6%. Federal action to lower that threshold or eliminate provider taxes, as has been proposed in the past, would therefore have financial implications for many states.

Few states made or are making significant changes to their provider tax structure in FY 2024 or FY 2025 (Table 4). The most common Medicaid provider taxes in place in FY 2024 were taxes on nursing facilities (46 states) and hospitals (45 states), intermediate care facilities for individuals with intellectual disabilities (32 states), MCOs42 (20 states), and ambulance providers (17 states). Seven states reported plans to add new taxes in FY 2025 (Nebraska and New Mexico adding a hospital tax, Massachusetts and New York adding a managed care tax, and Oregon, South Carolina, and Wyoming adding an ambulance tax). Maine will eliminate both a critical access hospital tax and a service provider tax (on certain community support services providers) in FY 2025. Twenty-three states reported planned increases to one or more provider taxes in FY 2025. Missouri was the only state planning tax decreases in FY 2025, reporting planned decreases in two of its taxes.43

Benefits

Context

Scope of Medicaid Benefits. State Medicaid programs must cover a comprehensive set of “mandatory” benefits, including items and services typically excluded from traditional insurance such as non-emergency medical transportation and long-term care. States may additionally cover a broad range of optional benefits defined in statute or permissible under other authorities such as Section 1115 waivers. In recent years, many state Medicaid programs have expanded their coverage of behavioral health, maternity, and dental services. States are also using Medicaid benefits to address social determinants of health (SDOH) and associated health-related social needs (HRSN) (e.g., housing, nutrition).

States may apply reasonable service limits based on medical necessity or to control utilization, but once covered, services must be “sufficient in amount, duration and scope to reasonably achieve their purpose.”44 ,45 There are additional benefit protections under federal statute for children and youth up to age 21.46 The Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit ensures access to any medically necessary service identified in federal Medicaid statute without limitation, including optional services the state otherwise does not cover. CMS recently released updated guidance for states reinforcing EPSDT requirements and outlining strategies and best practices to strengthen children’s access and the delivery of health care services under the EPSDT benefit.

The ability to cover optional benefits and place limits on items and services results in variation across states. State Medicaid benefit design is also impacted by prevailing economic conditions: states are more likely to adopt restrictions or limit benefits during downturns and expand or restore benefits as conditions improve. States used additional federal funds and Medicaid emergency authorities made available during the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) to maintain or even enhance access to needed services. This year, benefit expansions far outweigh benefit restrictions and limitations, consistent with prior years. New and enhanced benefits continue to advance state priorities by expanding access to a continuum of behavioral health services, supporting improved maternal and infant health, and addressing SDOH. In some states, new benefits may be targeted to specific populations or eligibility groups, such as justice-involved individuals, at risk youth, and individuals experiencing homelessness.

This section provides information about:

- Benefit changes

- Medicaid financing of the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

- Coverage of community violence intervention or prevention services

Findings

Benefit Changes

States were asked about benefit changes implemented during FY 2024 or planned for FY 2025, excluding eligibility expansions, telehealth policy changes, and changes made to comply with federal requirements. Benefit changes may be planned at the direction of state legislatures and may require CMS approval.

The number of states reporting new benefits and benefit enhancements continues to greatly outpace the number of states reporting benefit cuts and limitations (Figure 15 and Table 5). Forty-one states reported new or enhanced benefits in FY 2024, and 38 states reported plans to add or enhance benefits in FY 2025.47 Only two states (Nevada and Texas) reported eliminating or restricting benefits, both states taking action in FY 2024. There are additional details about benefit enhancements or additions in select benefit categories below (Figure 16).

Behavioral Health Services. Behavioral health services are not a specifically defined category of Medicaid benefits. Some fall under mandatory Medicaid benefit categories (e.g., physician services). States may also cover behavioral health services through optional benefit categories (e.g., rehabilitative services). Behavioral health services for children are particularly comprehensive due to Medicaid’s EPSDT benefit for children. Mental health and substance use disorder (SUD) services continue to be one of the most frequently reported categories of benefit expansions. Consistent with trends in recent years, states reported expanding services across the behavioral health care continuum. For FY 2024 and 2025, in conjunction with the ongoing implementation of the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, there was a particular focus on enhancing crisis services and expanding the availability of other services at home and in the community. States also continue to invest in more coordinated and integrated physical and behavioral health care, including reimbursement for interprofessional consultation, adding coverage for services provided under the Collaborative Care Model (CoCM), and implementing or expanding Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs).48

- Crisis Services. At least eleven states49 reported benefit actions related to the addition or expansion of crisis services, including seven states (Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, and West Virgina) enhancing their mobile crisis response and three states (Connecticut, Louisiana, and Nebraska) adding or expanding crisis services for youth. For example, Connecticut opened and added coverage of services in Children’s Urgent Crisis Centers for children and youth experiencing a behavioral health crisis in FY 2024.

- Contingency Management. Contingency management is an evidence-based psychosocial therapy that uses incentives to motivate and reinforce behavior changes that promote recovery from stimulant use disorder and other SUDs.50 Delaware reported recent approval under a Section 1115 waiver of a 24-week contingency management program for individuals with stimulant use disorder and a 64-week program for pregnant and postpartum individuals with opioid use disorder.51 Three additional states (California, Montana, and Washington)52 have already implemented and/or received CMS approval to implement a contingency management program and at least four states (Hawaii, Michigan, Rhode Island, and West Virginia)53 have requests pending. For example, West Virginia reported a pending Section 1115 waiver request enhancing covered SUD services, including expanded peer supports, expanded secure withdrawal management and stabilization services, the addition of recovery housing and contingency management services, and implementation of quick response teams for SUD emergencies.54

- Physical and Behavioral Health Integration. Four states (District of Columbia, Maryland, Nevada and South Carolina) reported benefit actions related to Medicaid coverage of the Collaborative Care Model (CoCM), an evidence-based model integrating behavioral health into primary care through collaborative care teams that include a case manager and a psychiatric consultant. Five states (Colorado, District of Columbia, New York, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina) added reimbursement of interprofessional consultation codes, following 2023 guidance from CMS reducing barriers to payment for the consulting provider and acknowledging the important role interprofessional consultation plays in improving access to behavioral health services.

Pregnancy and Postpartum Services. Medicaid covers more than 4 in 10 births nationally and the majority of births in many states. To help reduce maternal morbidity and mortality, as well as address disparities in maternal and infant health outcomes, states continue to expand and enhance covered prenatal, delivery, and postpartum services. As reported last year, these benefit enhancements are happening alongside the extension of Medicaid postpartum coverage in many states. Fourteen states reported adding coverage of doula services in FY 2024 or FY 2025.55 Eight states reported new benefits to help parents initiate or maintain breastfeeding, including breast pumps, human donor milk, and lactation consultation.56

- South Dakota reported a new enhanced care coordination program for pregnant individuals designed to increase utilization of timely prenatal and postpartum services.57 In FY 2025, Nebraska is launching its Prenatal Plus Program for at risk pregnant individuals pursuant to LB 857, which includes nutrition counseling, psychosocial counseling and support, education and health promotion, breastfeeding support, and targeted case management.

- New Jersey is the second state in the nation implementing a statewide universal home visiting program to help improve maternal and infant health. The state’s Medicaid program is also piloting programs to provide evidence-based home visiting services for up to 500 families each year58 and medically indicated home-delivered meals for pregnant individuals with diabetes.

- Tennessee is the first state to receive CMS approval to cover diapers for the first two years of a child’s life under its TennCare 1115 waiver. Delaware also received approval under its Section 1115 waiver to expand its Postpartum Nutrition Supports Initiative pilot and cover home-delivered meals or medically appropriate food boxes, as well as a weekly supply of diapers and wipes, for 12 weeks following delivery.

- Massachusetts reported providing temporary housing assistance (up to six months) for pregnant individuals and families who are experiencing homelessness and participating in the state’s Emergency Assistance Family Shelter program.59

Preventive Services. States are required to provide comprehensive preventive care to children through the EPSDT benefit, and states must cover certain preventive services for adults eligible under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion; however, this coverage is not required for “traditional” Medicaid adults. In this year’s survey, states reported benefit actions related to testing, screenings, vaccinations,60 and contraceptives. Some states also report expanding access to preventive services by newly adding coverage of pharmacist services allowable under their scope of practice (Illinois, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Wyoming) and adding local health departments to providers that may be reimbursed for screenings and other services (Texas).

- Two states reported covering at home testing and screening services. Pennsylvania added coverage of at home sexually transmitted infection (STI) test kits. Wyoming added coverage of Cologuard® at home colorectal screening tests to help increase colorectal cancer screening rates.

- Three states (Louisiana, Mississippi, and New Hampshire) reported addition or expansion of smoking cessation counseling services beyond required benefits and covered populations.

Services Targeting Social Determinants of Health (SDOH). Outside of Medicaid home and community-based services programs, state Medicaid programs have more limited flexibility to address enrollee social needs (e.g., housing, food, transportation, etc.). Certain options exist under Medicaid State Plan authority as well as Section 1115 waiver authority to add non-clinical benefits. In 2022, CMS released a new framework for covering health-related social needs (HRSN) services under Section 1115 waivers, expanding flexibility for states to add certain short-term housing and nutrition supports as Medicaid benefits (building on CMS guidance from 2021). Additional guidance and resources that identify allowable HRSN services and supports were released by CMS in late 2023. In this year’s survey, states continued to report services targeting SDOH, including housing services and supports, nutrition services, and medical respite.