2012 Survey of Americans on the U.S. Role in Global Health

Section 5: Visibility and Attention to Global Health

Declining Awareness/Visibility Of Global Health Issues

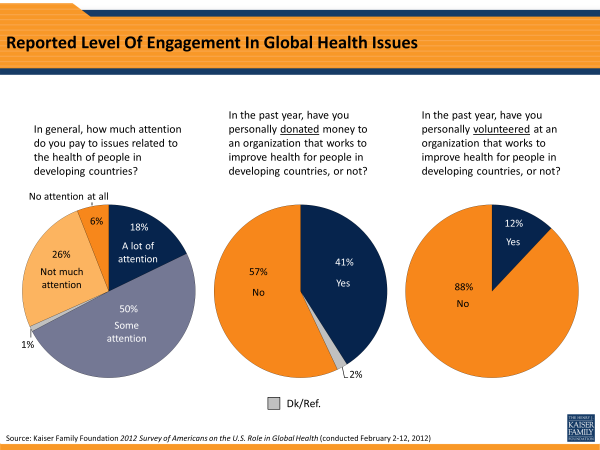

One challenge for those looking to increase the public’s level of support for U.S. spending on global health is that there are some indications that visibility of the issue may have declined somewhat since the summer of 2010. This decline may not be surprising given that 2012 is an election year, and one in which the news has continued to be dominated by the economic problems facing the country. While a majority of the public reports paying at least “some” attention to issues related to health in developing countries, fewer than one in five (18 percent) say they pay “a lot” of attention to these issues. The share saying they pay at least “some” attention is down somewhat, from 75 percent in August 2010 to 68 percent in 2012.

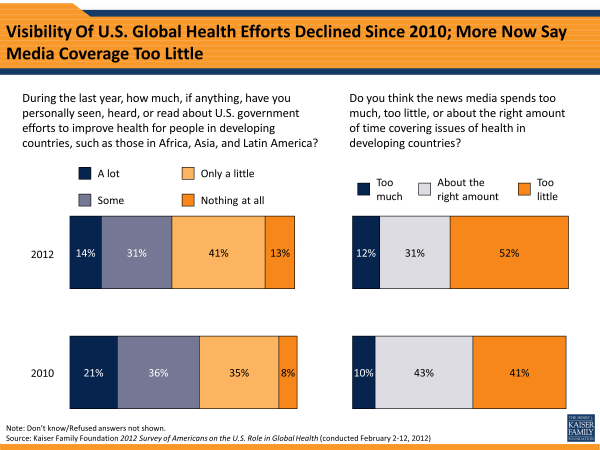

Similarly, there’s been a decline in the share saying they’ve heard more than a little in the past year about U.S. government efforts to improve health for people in developing countries. Currently, 45 percent say they’ve heard “a lot” (14 percent) or “some” (31 percent), down from a total of 57 percent who reported hearing “a lot” (21 percent) or “some” (36 percent) in 2010.

In light of this decline in visibility, the public has become somewhat more likely to say the news media is not devoting enough time to covering issues of health in developing countries. Currently, roughly half (52 percent) say the news media spends too little time on the topic, up from 41 percent in 2010. At the same time, the share who say the media spends about the right amount of time on the issue declined from 43 percent to 31 percent, while about one in ten continue to believe the media devotes too much time to the issue.

Age Differences In Support, Optimism, And Attention

While there is a lot of agreement across various demographic groups on questions of U.S. global health policy, some distinct age trends emerge in this survey. Compared with their older counterparts, younger adults are more likely to support increasing U.S. spending on health in developing countries, more optimistic that spending will lead to progress and will bring various benefits to the U.S., and less skeptical about the amount of U.S. global health spending lost through corruption.

For example, more than half of adults under age 30 (53 percent) think the U.S. currently spends too little on health in developing countries, compared with just 18 percent of those ages 65 and older. And while a majority of those ages 50 and older feel that the U.S. contributes more than its fair share compared to other donor nations, just about a quarter of 18-29 year-olds feel the same way. Perhaps reflecting the optimism of youth, a clear majority (62 percent) of adults under 30 believe that more spending from the U.S. and others will lead to meaningful progress in improving health in developing countries, while a similar majority of seniors (57 percent) think more spending won’t make much difference (those between the ages of 30-64 are more split). Younger Americans are also more likely than older ones to believe that spending to improve health in developing countries helps improve the U.S. image in the world, protects the health of Americans at home, and is helpful for the U.S. economy and national security. And seniors are more than twice as likely as those under 30 to believe that at least 75 cents of each U.S. dollar spent on health in developing countries is lost through corruption (34 percent vs. 15 percent).

At the same time, younger adults are less likely than older Americans to report paying close attention to the issue of health in developing countries, and less likely to report hearing news about U.S. global health efforts in the past year. Just a third (33 percent) of those ages 18-29 say they’ve heard “a lot” or “some” in the past year about U.S. government efforts to improve health in developing countries, compared with six in ten of those ages 65 and older.

| Figure 28: Views on U.S. Global Health Spending by Age | ||||

| 18-29 | 30-49 | 50-64 | 65+ | |

| U.S. spending to improve health in developing countries is… | ||||

| …too much | 12% | 22% | 23% | 29% |

| …about right | 27 | 35 | 38 | 36 |

| …too little | 53 | 30 | 29 | 18 |

| Compared to other wealthier countries, the U.S. contributes… | ||||

| …more than its fair share | 26 | 43 | 55 | 52 |

| …about its fair share | 42 | 37 | 31 | 32 |

| …less than its fair share | 23 | 14 | 10 | 9 |

| More spending from the U.S. and other countries… | ||||

| …will lead to meaningful progress in improving health | 62 | 51 | 46 | 34 |

| …won’t make much difference | 37 | 44 | 51 | 57 |

| Percent who say spending money on health in developing countries… | ||||

| Helps improve the U.S. image in the world | 72 | 64 | 52 | 44 |

| Helps protect the health of Americans | 73 | 81 | 72 | 65 |

| Helps the U.S. economy | 51 | 46 | 39 | 32 |

| Helps U.S. national security | 56 | 46 | 41 | 34 |

| Percent who say cents of U.S. tax dollars spent on health in developing countries that are lost through corruption is… | ||||

| …less than 25 cents | 33 | 28 | 10 | 13 |

| …25-74 cents | 41 | 43 | 55 | 40 |

| …75 cents or more | 15 | 19 | 29 | 34 |

| During the last year, how much seen, heard, or read about U.S. government efforts to improve health in developing countries… | ||||

| …a lot/some | 33 | 41 | 49 | 60 |

| …only a little/none | 66 | 58 | 50 | 39 |

| How much attention you usually pay to health in developing countries… | ||||

| …a lot/some | 61 | 65 | 70 | 77 |

| …not much/none | 39 | 35 | 30 | 21 |

Three In Ten Name A Leader On Global Health; Barack Obama, Bill Gates, Bill Clinton Top List

Perhaps surprisingly given this low level of visibility, three in ten Americans are able to name a person they think of as a leader in efforts to improve health for people in developing countries. At the top of the list are President Barack Obama (named by 5 percent) and entrepreneur and philanthropist Bill Gates (named by 5 percent, which includes mentions of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation), followed by former President Bill Clinton (4 percent). Various other individuals were mentioned by about 1 percent of the public each, including former presidents Jimmy Carter and George Bush, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey, Bono, Angelina Jolie, Sean Penn, and George Clooney.