What’s at Stake for Access to Medication Abortion and the FDA in the Supreme Court Case FDA v. the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine?

On June 13, 2024, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (AHM) v. FDA that the AHM does not have standing to sue the FDA for injury. However, three state Attorneys’ Generals have intervened in this case in district court, and it is unclear how this action will shape the case when it goes back to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals and then back to the originating federal district court.

On March 26, 2024, the Supreme Court is scheduled to hear oral arguments in Food and Drug Administration (FDA) v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (AHM), and Danco Laboratories LLC v. AHM. While the Supreme Court stated in the Dobbs decision that it “returns the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives,” the outcome of this case could limit access to medication abortion throughout the country, including in states where abortion is legal and protected. The interest in this case expands far beyond the issue of access to mifepristone and abortion; many people are watching whether the Court will block the FDA’s independence in determining the conditions required to assure a drug’s safe use— something the Court has never done before.

What Is the Case?

In the case, AHM v. FDA, the plaintiffs contend the FDA did not act within its authority when it approved mifepristone (one of the two drugs used in the medication abortion regimen) and also when it revised the protocol for prescribing and dispensing the medication in 2016 and 2021 (See Table 1). The plaintiffs also claim that the approval violated an 1873 anti-obscenity law, the Comstock Act, which prohibits the mailing of any medication used for abortion. The plaintiffs claim they have legal standing, arguing they are injured because they must treat patients who present to the emergency room after taking mifepristone, forcing them to divert time from their other patients and violating their conscience rights.

Danco, the manufacturer of Mifeprex, the brand name of mifepristone, has intervened in this case and is a defendant along with the FDA. The FDA and Danco claim the FDA approved changes in the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) (special conditions FDA applies to some drugs) and other conditions for mifepristone use in 2016 after extensively reviewing the scientific evidence and 15 years of data reflecting the drug’s safety profile. Based on numerous studies, the FDA concluded mifepristone was safe to use up to 70 days gestation, misoprostol was effective and safe to use at home, and the efficacy and safety was the same with physicians and non-physician providers. The FDA also determined that the continued reporting of non-fatal adverse events by prescribers under the REMS was not warranted because of mifepristone’s safety record. During the COVID-19 public health emergency, the in-person dispensing requirement for mifepristone was enjoined by a court order for 6 months from July 2020 to January 2021. Based on the research and data collected during this period, the FDA found no indication that modification of the in-person dispensing requirement had increased adverse events. In April 2021, the FDA notified the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) that the agency would exercise enforcement discretion of the in-person dispensing requirement. In January 2023, the FDA formally amended the REMS, to permanently remove the in-person dispensing requirement, and adding a requirement that certified pharmacies can dispense mifepristone.

Lower Court Rulings

On April 7, 2023, Federal District Court Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk issued a ruling that would have blocked the FDA’s 2000 approval of mifepristone (See Tables 2 and 3). He ruled that the plaintiffs had standing to sue and were likely to succeed on the merits on their claims that the FDA acted “arbitrarily and capriciously” when approving mifepristone, and when it made changes to the rules for prescribing and dispensing the medication in 2016 and 2021. In addition, Judge Kacsmaryk found the plaintiffs had a substantial likelihood of prevailing on their claims that the FDA’s actions violate the Comstock Act by allowing mifepristone to be mailed to patients.

The FDA appealed the district court’s ruling to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals which also found that the plaintiffs have standing to bring the case but did not uphold the decision to order FDA to revoke mifepristone’s approval. Instead, the court ruled that the FDA acted improperly when changing the REMS. The court order would block the changes made in 2016 and 2021, rolling the dispensing and prescribing rules back to those in place in 2011. The effect of this would be to require in-person dispensing of the medication and permit only physicians to prescribe and dispense the medication, blocking the current ability of physicians, certified providers, and pharmacies to mail the drug. The 5th Circuit Court of Appeals did not base their decision on the Comstock Act, but the plaintiffs and the defendant both appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

What is the Supreme Court Considering?

The Supreme Court agreed to review the FDA’s appeal of the 5th Circuit decision but denied the plaintiffs’ appeal requesting the Court to review the FDA’s original approval of mifepristone from 2000. Therefore, the Court’s review is limited to two major questions: whether the plaintiffs have standing to bring the case and whether the FDA’s 2016 and 2021 actions to revise the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) and other conditions were arbitrary and capricious. The Court is not reviewing the FDA’s initial approval of mifepristone in the year 2000 nor the plaintiffs’ original claim that the FDA’s actions violated the Comstock Act.

Do the Plaintiffs Have Standing?

The first question the court must consider is whether the plaintiffs have legal standing to bring this case; without legal standing, the case does not proceed. In this case, the plaintiffs are doctors, associations and organizations that oppose abortion; none of them prescribe mifepristone. The issue of standing in the case has caught the attention of many pharmaceutical companies, which rely on the FDA’s decisions regulating drugs. Every drug has side effects. Many court watchers are concerned that if the Court rules that these plaintiffs have standing, then the door will be opened to anyone to bring a case against the FDA’s approval of any drug. The Pharmaceutical Companies, Executives, and Investors warn, “If allowed to stand, the decision below will invite a flood of meritless challenges to the FDA’s drug safety and efficacy decisions, including those brought by parties with no concrete interest at stake.”

The plaintiffs contend they are injured because the FDA has made mifepristone widely available and based on statistical probability, one of their members will likely have to treat a patient with side effects from taking mifepristone, which will force one of their members to act against their conscience in helping to terminate a pregnancy. The doctors assert that their injury is based on:

- having to divert time and resources away from their regular patients;

- mifepristone patients exposing them to greater liability and increased insurance costs;

- violation of their conscience when being forced to participate in an elective abortion and

- enormous stress and pressure.

The FDA asserts that the plaintiffs have failed to show any concrete injury: “All of respondents’ theories of injury reduce to the assertion that FDA’s changes to mifepristone’s conditions of use could marginally increase the risk that one of respondents’ seven identified doctors may be called upon to treat a woman who has chosen to take mifepristone and experiences an exceedingly rare serious adverse event—a scenario that can occur only at the end of a long chain of contingencies involving independent decisions by third parties.”

The 5th Circuit found that the doctors’ injuries are legally recognizable. If the Supreme Court limits standing based on the conscience violations injuries, then future litigation might be based on challenging the FDA’s approval of other drugs perceived to be controversial such as PrEP or medications for gender affirming care.

In their defense, the FDA and Danco contend that federal law allows doctors to refuse care based on a conscientious objection. In response, the AHM cites to the July 2022 Department of Health and Human Services guidelines issued by the Biden Administration after the Dobbs ruling, which states that the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) requires hospitals to provide abortions as stabilizing care when that care is necessary to stabilize a patient. The 5th Circuit agreed with AHM that the federal law does not alleviate the doctors’ conscience injury. (The Supreme Court is considering a different case about the interaction between EMTALA, the federal law that requires that hospitals to stabilize the health of patients presenting at emergency room and Idaho’s abortion ban this term.)

Were the FDA’s 2016 and 2021 Actions Arbitrary and Capricious?

Congress has authorized the FDA to review and approve drugs. At issue in this case, is the standard by which the FDA may alter the conditions for use, including the REMS, for a drug. The statute authorizing the FDA to use and modify REMS requires the FDA to balance the drug’s risks against the burden on patient access but does not prescribe a specific methodology for this review. AHM claims the FDA violated the Administrative Procedures Act (APA) when it failed to consider the cumulative effect of all the 2016 changes or to provide a satisfactory explanation for its decision not to study the cumulative effect of the changes.

The 5th Circuit agreed with AHM and ruled that the FDA failed to examine the cumulative effect of all the proposed changes in 2016 through a single controlled study and did not explain why it did not do so. In addition, they found that in 2021, the FDA relied on incomplete data because, in 2016, the FDA removed the requirement for prescribers to report adverse events beyond the FDA’s standard reporting requirements. Further, the court found that the FDA relied on research that did not affirmatively support the suspending of the in-person dispensing requirement. The FDA maintains there is no requirement for the agency to conduct one study with all the proposed changes. The FDA contends that “[a] reviewing court’s only role is to ensure ‘that the agency has acted within a zone of reasonableness’ and ‘has reasonably considered the relevant issues and reasonably explained the decision.’” In addition, the FDA reports that the studies they relied on to make the REMS modifications support their conclusions that mifepristone is safe and effective without the need for mandatory in-person dispensing. They further maintain the Court should defer to their judgment as the agency has the expertise in this area–not the Court.

Many of the “friend of the court briefs” (amicus curiae) warn that the Supreme Court could destabilize the regulatory process for approving drugs in the U.S. For example, The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America warns that the 5th Circuit decision “threatens to disrupt the cycle of drug development and to upend the investment backed expectations of industry that ultimately undergird the availability of innovative medicines on which patients rely.” However, presenting an opposing perspective, former leaders of the Trump Administration claim that the FDA gave Danco special treatment, and if allowed to stand, other companies will expect this treatment.

Potential Impact on Medication Abortion Access and the FDA

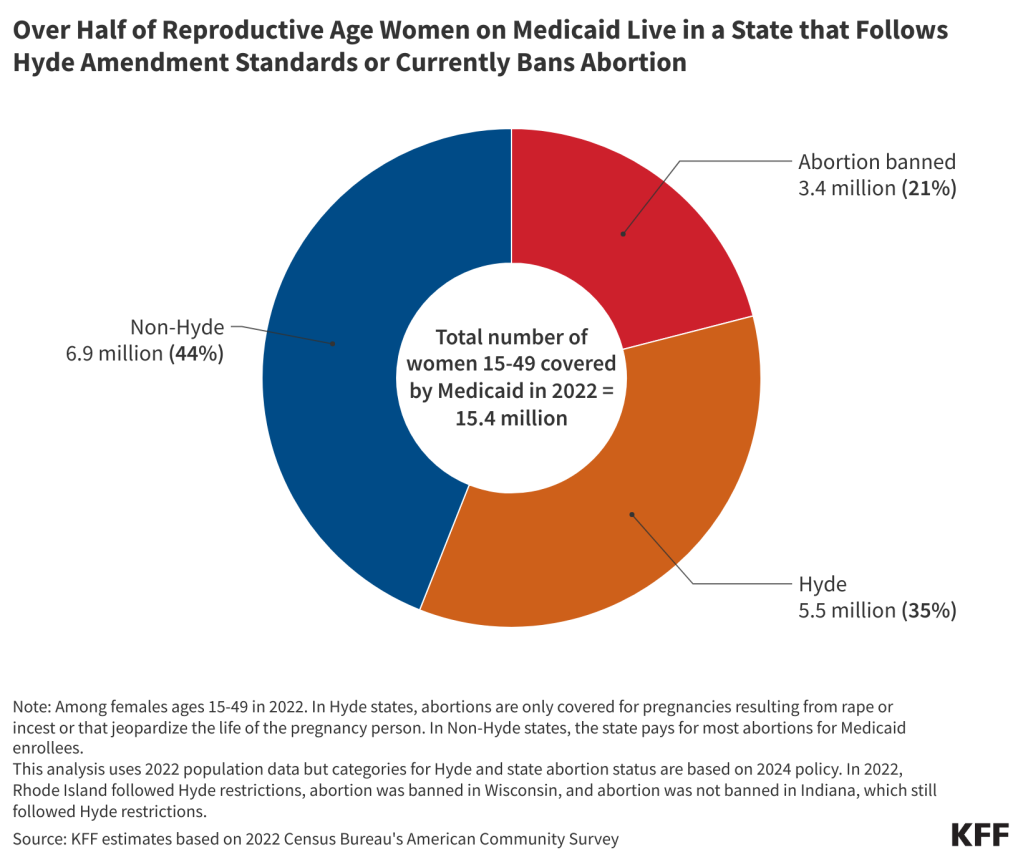

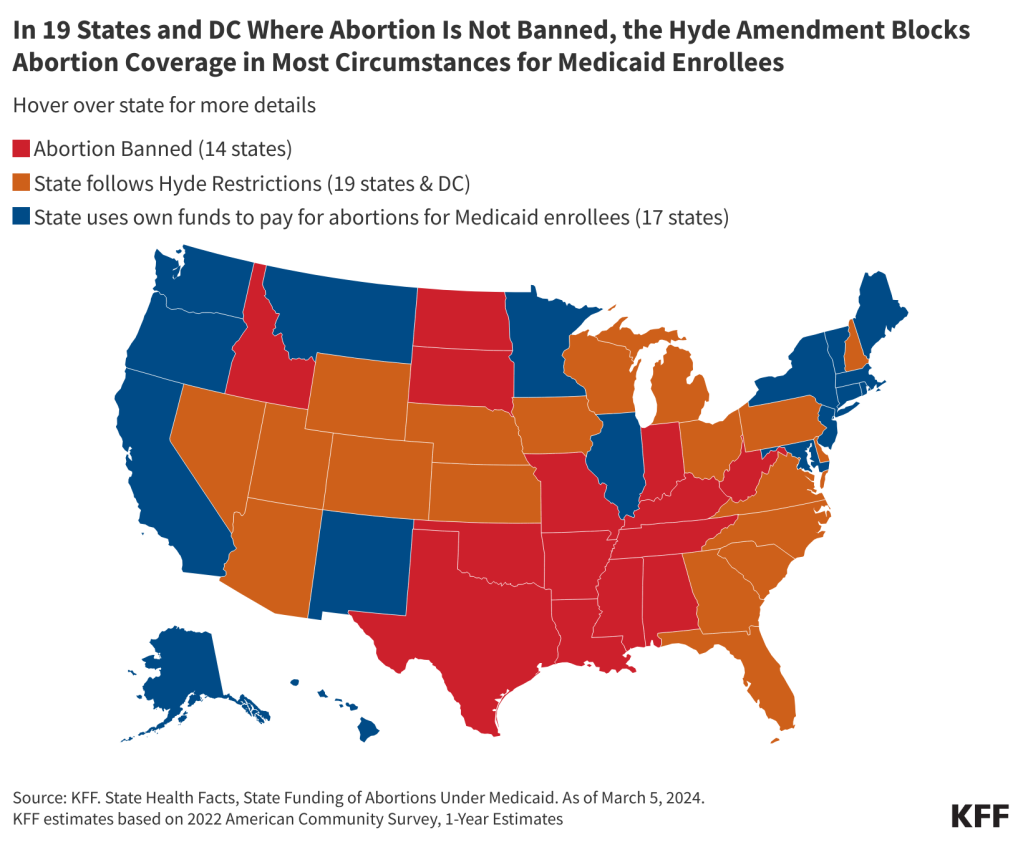

The Supreme Court is specifically reviewing the rules that allow people to access mifepristone via telehealth without an in-person visit. Medication abortion accounts for nearly two thirds (63%) of abortions in the United States. In 2022, 789 facilities offered medication abortion, and 243 of these facilities in 27 states provided telehealth medication abortions with an option to mail the abortion pills to the patients.

The Society of Family Planning estimates that 16% of all abortions in September 2023 were provided via telehealth, with nearly 14,000 telehealth abortions that resulted in medications being dispensed via mail. Many of these abortions were performed by virtual-only clinics that offer medication abortion through telehealth. These new clinics were not an option for abortion seekers until 2021, and the prevalence of virtual-only abortion providers has been growing since.

The court’s decision could also substantially reduce the number of abortions that could occur using mifepristone. The 2011 REMS permitted mifepristone to be used up to 7 weeks gestation, while the 2016 REMS expanded access to mifepristone up to 10 weeks gestation. According to the 2021 CDC abortion surveillance data, more than four in ten medication abortions occur 7 weeks and beyond (See Figure 1).

If the Supreme Court affirms the 5th Circuit’s decision to roll back the requirements to the 2011 protocols, the new protocols the FDA has established removing the in-person dispensing requirement, permitting telehealth abortions, and establishing the process for pharmacies to become certified to dispense mifepristone would be eliminated.

The case also raises questions about the role of the courts in reviewing the FDA’s determinations about a particular drug. This is the first case to ask the Supreme Court to overrule an FDA decision that a drug is safe and effective. The outcome of this case could have far-reaching implications for the FDA’s authority to continue to regulate not only mifepristone, but a wide range of other drugs, including those that could be perceived to be controversial today and in the future. Depending on how the Supreme Court rules, we may see the door opened to new litigation, and a major shift in the FDA’s authority in regulating drugs.