What the Outcome of the Election Could Mean for Medicaid

While Medicaid policy may not be a central issue candidates are talking about, the outcome of the election could have major implications for Medicaid, the primary program providing comprehensive coverage for over one in five low-income Americans. Medicaid is jointly financed by the federal government and states and administered by states within broad federal guidelines. Medicaid represents nearly one in five dollars spent on health and disproportionately finances safety-net hospitals and clinics, behavioral health care, and long-term services and supports (LTSS) in the community and nursing homes for seniors and people with disabilities. Medicaid has become a major part of our health care system, with two-thirds of Americans having a connection to Medicaid. Public opinion polling shows Medicaid has broad support across political parties.

This brief highlights major policy differences under the Biden-Harris Administration and the Trump Administration on key Medicaid topic areas. The brief examines the records and proposed budgets under President Biden and Vice President Harris and former President Trump as well as major legislative proposals that former President Trump supported. Budget proposals often include policy proposals that would require Congressional action to enact. The 2024 Republican Party platform calls for new affordable health care and prescription drug options with protections for Medicare and seniors but does not include any details about Medicaid policy. To help inform the range of options that could be considered under a Trump presidency, this brief also examines Medicaid policies included in the Republican Study Committee (RSC) FY 2025 budget and the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025. Former President Trump has not endorsed these proposals, though there would likely be a push for them from conservative groups and Republicans in Congress if Trump wins the election. Policy differences are highlighted across the following key Medicaid topic areas, with more detail about candidate records and specific sources in the Appendix.

- ACA Medicaid Expansion

- Financing

- Eligibility, Benefits, and Cost-Sharing

- Prescription Drugs

- Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS)

- Managed Care

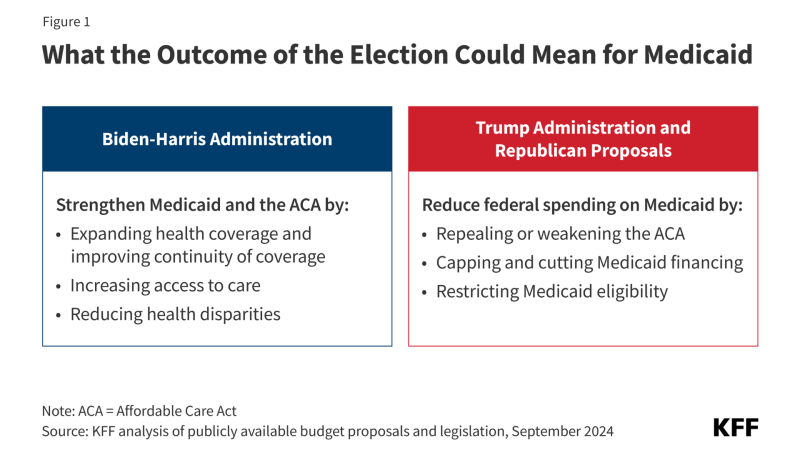

The analysis finds that Vice President Harris and former President Trump have vastly different records, views on, and policy proposals for Medicaid (Figure 1). More broadly, as KFF President and CEO Drew Altman recently wrote, “Republicans and Democrats have fundamentally different world views of the program.”

Biden-Harris Administration policy proposals have generally focused on efforts to “protect and strengthen Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act (ACA)” by expanding health coverage and improving continuity of coverage, reducing the rate and number of uninsured, expanding access to care, and reducing health disparities. These policies generally maintain or increase federal Medicaid spending.

Former President Trump has not talked specifically about Medicaid in the current campaign, but his record as president and proposals from Republican groups include plans to repeal or weaken the ACA, cap and reduce Medicaid financing, and restrict Medicaid eligibility, with the overarching goal of reducing federal spending on Medicaid. Estimates of savings range widely, from a $4.5 trillion reduction over 10 years (over a 50% reduction) under the RSC FY 2025 budget proposal, to earlier Congressional Republican proposals that would have reduced Medicaid spending by 25% or one-third, to other proposals with smaller overall reductions but large shifts in spending across states. Reductions in federal spending generally shift risk and costs to states as well as enrollees and would likely increase the number of uninsured people.

Key Takeaways

Vice President Harris inherits the record of the current administration but has also independently focused on reproductive rights and policies aimed at reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. Major Biden-Harris Administration efforts across key Medicaid topic areas include:

- ACA Medicaid Expansion: The Biden-Harris Administration implemented policies to strengthen the ACA, including enacting legislation with an additional fiscal incentive for states to adopt Medicaid expansion. The administration also proposed a plan to close the coverage gap in states that have not expanded Medicaid, but it did not pass Congress.

- Financing: The administration built on the existing Medicaid financing framework by expanding federal matching funds for priority areas, such as incentivizing states to expand Medicaid home and community-based services (HCBS).

- Eligibility, Benefits, and Cost-Sharing: The Biden-Harris Administration enacted legislation to expand access to health insurance coverage by requiring 12-month continuous eligibility for children and creating an option for states to extend postpartum coverage to 12 months as well as cover certain justice-involved youth. During the unwinding of the Medicaid continuous enrollment provision, the administration issued guidance and provided states with additional waiver flexibilities to help eligible enrollees retain coverage.

- Prescription Drugs: The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), enacted during the Biden-Harris Administration, included several provisions to lower prescription drug costs and reduce drug spending by the federal government, including allowing the federal government to negotiate prices for some drugs in Medicare and requiring that drug manufacturers pay rebates for price increases above inflation in Medicare. Within Medicaid specifically, the administration has enacted policies (as well as proposed additional policies that did not pass) to expand and strengthen the Medicaid drug rebate program (MDRP).

- Long-Term Services and Supports: The administration enacted legislation to increase federal funding for Medicaid HCBS and issued regulations to increase access to Medicaid HCBS, promote higher payment rates for home care workers, and establish minimum staffing requirements in nursing facilities. President Biden and Vice President Harris have called for additional, permanent federal funding for HCBS, which did not pass.

- Managed Care: The Biden-Harris Administration issued updated Medicaid managed care regulations aimed at improving access to care, quality, health outcomes, and health equity as well as took action to improve Medicaid managed care monitoring, oversight, and transparency.

Specific Republican policies, both during and after the Trump Administration, across key Medicaid topic areas include:

- ACA Medicaid Expansion: The Trump Administration proposed and supported unsuccessful efforts to repeal and replace the ACA, including Medicaid expansion. More recent Republican proposals, the RSC FY 2025 budget and Project 2025, do not specify a complete repeal but seek to reduce the higher match rate for the Medicaid expansion group and eliminate expanded Marketplace subsidies.

- Financing: The Trump Administration proposed and supported legislative proposals to limit federal Medicaid spending by restructuring Medicaid financing into a block grant or per capita cap. The RSC FY 2025 budget and Project 2025 also suggest a block grant or cap as well as changes in federal matching payments.

- Eligibility, Benefits, and Cost-Sharing: The Trump Administration approved waivers that included work requirements as a condition of Medicaid eligibility, premiums, and other eligibility restrictions. The RSC FY 2025 budget and Project 2025 also propose restricting Medicaid eligibility, benefits, and continuity of coverage, including actions such as imposing work requirements, eliminating minimum eligibility thresholds, and providing state flexibility to redesign and eliminate certain benefits.

- Prescription Drugs: The Trump Administration aimed to address high drug costs by allowing the importation of drugs from Canada and encouraging states to submit waivers to create closed formularies. Both the RSC FY 2025 budget and Project 2025 seek to repeal the IRA, citing its implications for drug innovation.

- Long-Term Services and Supports: The Trump Administration reduced federal oversight over nursing facilities, but more recent Republican proposals give little indication of LTSS policy priorities.

- Managed Care: The Trump Administration changed Medicaid managed care rules, including relaxing Medicaid managed care plan network adequacy rules and requirements for beneficiary protections. Project 2025 proposes to reform and increase oversight of Medicaid managed care but doesn’t provide specifics.

Details of Medicaid Policies and Proposals

Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid Expansion

Context: The ACA expanded Medicaid coverage to nearly all adults up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($20,783 for an individual in 2024), but it is effectively an optional policy for states following a ruling by the Supreme Court. As of summer 2024, 41 states including DC have expanded Medicaid while 10 states have not, leaving 1.5 million uninsured people in the “coverage gap” (adults who have incomes above their state’s eligibility for Medicaid but below poverty, making them ineligible for subsidies in the ACA Marketplaces). The ACA expansion group is financed with a 90% federal match rate or “FMAP”, so states pay 10% of the costs for the expansion group. Data from June 2023 show almost 24 million adults were enrolled in Medicaid through the ACA expansion eligibility pathway. Total spending for this population in fiscal year 2022 was over $155 billion, including $138 billion in federal spending and $17 billion in state spending. The ACA also created health insurance exchange markets, or Marketplaces, which offer subsidized coverage to those who are not eligible for Medicaid and who do not have access to other affordable coverage.

Biden-Harris: The Biden-Harris Administration enacted legislation to strengthen the ACA, including an additional fiscal incentive for states to adopt the ACA Medicaid expansion and temporary enhanced subsidies for Marketplace coverage. The Biden-Harris Administration has also taken action to increase funding for Marketplace outreach and navigators and has supported legislation to close the coverage gap (that never passed). Four new states have adopted Medicaid expansion since Biden and Vice President Harris took office, and the number of people with Marketplace coverage has grown significantly under the administration. The Biden-Harris Administration’s latest budget builds on these actions by proposing to make the enhanced Marketplace subsidies permanent and continuing to call for closing the coverage gap. As a part of a recent campaign speech focused on economic issues in North Carolina, Vice President Harris also highlighted health proposals including extending the enhanced Marketplace subsidies.

Trump and Republican Proposals: Former President Trump modeled proposals included in his 2019 and 2020 budgets on the Graham-Cassidy amendment, which called for repealing and replacing the ACA (the FY 2021 budget was more vague about health reform proposals). Other legislation introduced but not enacted during the Trump presidency — the American Health Care Act (AHCA) and the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) — also called for repealing and replacing the ACA. More recently released Republican proposals do not specify a complete repeal of the ACA, but the RSC FY 2025 budget proposes to eliminate the expanded ACA subsidies and reduce the FMAP for the Medicaid expansion group. Project 2025 also proposes “a fairer and more rational match rate” for the Medicaid expansion group.

Tradeoffs: The Biden-Harris Administration proposals would support expanded coverage but increase federal spending. Republican proposals would eliminate or severely limit access to affordable health insurance coverage for low-income adults but would reduce federal spending. Rolling back the ACA Medicaid expansion could also have implications for state fiscal conditions and providers. The federal government pays the vast majority of expansion costs, and the literature shows that states expanding Medicaid under the ACA have realized budget savings, revenue gains, overall economic growth as well as observed positive effects on the finances of hospitals and other health care providers. Recent KFF polling finds that more than three in four (78%) enrollees and two-thirds of all adults in a non-expansion state say their state should expand Medicaid to cover more low-income uninsured people. Among the public overall, expanding Medicaid is largely split along partisan lines.

Financing

Context: Medicaid is an entitlement program, meaning individuals who meet eligibility requirements are guaranteed coverage and states are guaranteed federal matching funds without a cap for qualified services provided to eligible enrollees. The FMAP (federal match rate) for most Medicaid enrollees is determined by a formula in the law that provides a match of at least 50% and provides a higher federal match rate for states with lower per capita incomes. There are also higher match rates for certain services and populations like the ACA expansion group (90%). Medicaid also provides “disproportionate share hospital” (DSH) payments to hospitals that serve a large number of Medicaid and low-income uninsured patients to offset uncompensated care costs. Medicaid represents almost $1 out of every $5 spent on health care in the U.S. and provides significant financing for hospitals, community health centers, physicians, nursing homes, and community-based LTSS.

For state budgets, Medicaid is a spending item and at the same time the largest source of federal revenues. To help finance the state share of Medicaid, states can use funding from local governments or revenue collected from provider taxes and fees to help finance the state share of Medicaid within certain limits and rules.

Biden-Harris: The Biden-Harris Administration has built on the existing financing framework by expanding federal matching funds for priority areas, such as incentivizing states to expand Medicaid or Medicaid home and community-based services. The administration’s latest budget proposal (along with prior budgets) keeps the Medicaid financing system as is under federal law and also provides funding to improve program integrity and prevent fraud.

Trump and Republican Proposals: The Trump Administration and other Republican proposals examined aim to significantly limit federal Medicaid spending by restructuring Medicaid financing into a block grant or a per capita cap where states would receive a pre-set amount of funding for Medicaid in total or per enrollee. Typically, a base year of Medicaid spending would be established and then the aggregate or per enrollee caps would increase by a specified amount each year, typically tied to inflation or inflation plus some percentage. To generate federal savings, the total amount of federal spending would be less than what is expected under current law. Program costs in excess of the total or per enrollee caps would not be matched by the federal government, leaving states to cover these costs or reduce Medicaid spending. Proposals that cap federal Medicaid funding could also eliminate the entitlement to coverage or federal minimum requirements for eligibility and benefits. The Trump Administration FY 2020 budget proposed to convert federal Medicaid funding to a per capita allotment; this change along with other health care adjustments totaled $1 trillion in spending reductions relative to estimated spending under current law over 10 years. More recent Republican proposals, the RSC FY 2025 budget and Project 2025, call for capped Medicaid spending as well as a match rate of 50% for all eligibility groups and services (RSC FY 2025 budget) or a “blended” match rate (Project 2025).

Proposals that fundamentally change the financing structure and entitlement nature of the program would require legislative change and would have broad implications across all areas of Medicaid; however, even without legislative changes, presidential administrations have options to issue regulations or guidance as well as approve demonstration waivers which could result in incremental program changes. In lieu of major legislative changes to Medicaid financing, former President Trump also issued guidance and encouraged states to apply for Healthy Adult Opportunity waivers that offered states “extensive flexibility” to cover certain groups of enrollees in exchange for limits in federal financing and access to shared savings for spending below the set cap; however, no states were approved for such waivers. In addition to restructuring Medicaid financing, Republican proposals also include provisions to restrict the use of provider taxes, combat Medicaid improper payments, and improve program integrity.

Tradeoffs: Republican proposals would substantially reduce federal Medicaid spending and allow states additional flexibility to administer their programs. KFF analysis has found that Medicaid financing caps would also limit the ability of states to meet changing needs and demands (e.g. changing state demographics, emerging high-cost drugs, etc.), and could lock-in current state spending patterns that reflect historic Medicaid policy choices. States would likely have to make choices to cover fewer people, cut benefits, and/or lower payment rates for providers (though Medicaid is typically already the lowest payer), leaving more people uninsured and reliant on safety net providers or unable to access care. While states may gain additional flexibility to administer their programs, these new options are not likely to make up for significant cuts in federal spending. States would likely face challenges to maintaining coverage, with certain states (like those with higher health care costs or needs) more at risk. Proposed changes to the FMAP floor or the ACA match rate could reduce federal spending but have disparate effects on states. States with higher per capita incomes could be most affected by calls to lower the FMAP floor while states with lower per capita incomes could be most affected by proposals to have a uniform match rate of 50%. Across many Republican proposals, expansion states would fare worse than non-expansion states with proposals to reduce the expansion match.

Recent KFF polling found that nearly 9 in 10 (86%) Medicaid enrollees want Medicaid to largely continue as it is today, while one in ten (14%) support changing Medicaid to cap federal funding and give states greater flexibility in designing their programs. Somewhat fewer adults overall – though notably still a large majority – say the same (86% vs. 71%). KFF polling has also found that majorities of voters are worried about fraud, waste, and abuse in Medicaid, Medicare, and Social Security as well as in private health insurance plans. Both parties support reducing waste, fraud, and abuse and focusing on oversight of managed care plans and providers; however, there was more of a focus on reducing errors in eligibility determinations during the Trump presidency compared to a focus on oversight of providers and managed care plans during the Biden-Harris Administration.

Eligibility, Benefits, and Cost-Sharing

Context: Medicaid provides financing for a variety of groups and for a wide range of services. To participate in Medicaid and receive federal matching funds, states must meet minimum federal requirements related to who is eligible and what services must be covered. States must provide certain mandatory benefits (e.g., hospital, physician, and nursing home services) to mandatory populations (e.g., children and low-income pregnant people) without waiting lists or enrollment caps. States may also receive federal matching funds to cover “optional” services (e.g., adult dental care and home and community-based services ) or “optional” groups (e.g., children and pregnant people with income above the limits established for mandatory populations). States do have the flexibility to charge premiums and cost-sharing for some enrollees, though federal law limits the extent to which states can impose these measures.

Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waivers offer states an avenue to test new approaches in Medicaid that differ from what is required by federal statute. While there is great variation in how states have used waivers over time, waivers generally reflect priorities identified by states and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). States may obtain “comprehensive” Section 1115 waivers that make broad changes in Medicaid eligibility, benefits, provider payments, and other program rules; other waivers may be narrower and address specific populations or benefits.

Biden-Harris: The Biden-Harris Administration enacted the 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act, which required states to implement 12-month continuous eligibility for children, made permanent the option for states to extend postpartum coverage to 12 months, and provided states with the option to cover certain justice-involved youth. Vice President Harris has called for reducing maternal mortality and morbidity, including encouraging states to adopt the postpartum Medicaid coverage extension. The Biden-Harris Administration also finalized a rule that aligns and streamlines enrollment and renewal requirements for most individuals in Medicaid; creates timeliness requirements for redeterminations of eligibility; eliminates access barriers for children enrolled in CHIP, such as waiting periods; and facilitates transitions between Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace coverage. During the unwinding of the Medicaid continuous enrollment provision, the administration issued guidance and identified a range of strategies and waiver flexibilities states could adopt to limit coverage losses among those who remained eligible.

For the 2025 budget year, the Biden-Harris Administration proposes to require 12 months of postpartum Medicaid coverage, expand state options to provide continuous eligibility for children for multiple years, and eliminate fees and premiums in separate CHIP programs. Further, the Biden-Harris Administration continues to encourage waivers to expand coverage, reduce health disparities, address the social determinants of health, and help individuals transition out of incarceration.

Trump and Republican Proposals: Consistent with the Trump Administration and older legislative proposals, recent Republican proposals would make a number of changes that limit Medicaid eligibility, benefits, and continuity of coverage as well as impose work requirements for enrollees. More specifically, both the RSC FY 2025 budget and Project 2025 propose work requirements, making changes to eligibility thresholds (like eliminating minimum income eligibility for children), establishing flexible accounts (like health savings accounts) to pay for health care, and providing state flexibility to redesign and eliminate certain benefits. Project 2025 also proposes targeted time limits or lifetime caps on benefits, requiring more frequent eligibility redeterminations, and increasing premiums and cost-sharing for some individuals. Capping federal funding, as all Republican proposals examined support, would also have implications for the entitlement (guarantee of coverage for eligible individuals that is part of current law) though none of the proposals clearly note what would become of the entitlement or minimum eligibility thresholds. Section 1115 waiver priorities promoted and approved under former President Trump included eligibility restrictions such as work and premium requirements and other conditions on coverage that did not require legislative changes to advance.

Tradeoffs: The Biden-Harris Administration proposals would expand access to coverage as well as keep more individuals connected to care over time but could increase spending. Continuous eligibility policies, which have been embraced by the Biden-Harris Administration, have been shown to lower rates of “churn,” or the temporary loss of Medicaid coverage in which enrollees disenroll and then re-enroll within a short period of time. When individuals churn on and off coverage, they experience gaps in coverage that can limit access to care and lead to delays in getting needed care. The Biden-Harris Administration proposals would also likely increase enrollment among eligible children by eliminating CHIP premiums and enrollment fees, which can pose barriers to coverage.

In contrast, Republican proposals support more frequent and robust eligibility redetermination processes to ensure that only eligible individuals remain enrolled in the program. However, with more frequent data checks, eligible individuals are at risk for losing coverage if they do not receive or understand notices or forms requesting additional information to verify eligibility or do not respond to requests within required timeframes. Some enrollees, such as working individuals whose monthly income fluctuates, would be at a higher risk of churning on and off Medicaid than others. In addition, most Republican proposals include work requirements. The data show that the majority of Medicaid enrollees are already working, and available implementation data suggests that Medicaid work and reporting requirements are confusing to enrollees and result in substantial coverage loss among eligible individuals who experience challenges with reporting requirements. Republican proposals also provide states additional flexibility by reducing requirements to cover certain benefits and allowing more premiums and cost-sharing. Overall, Republican proposals describe these changes as aligning Medicaid with private insurance, and they would likely reduce federal Medicaid spending. Because people on Medicaid have lower incomes and are sicker than the general population, these changes are also likely to pose barriers to enrollees’ ability to maintain coverage and access needed health care.

Prescription Drugs

Context: All state Medicaid programs have opted to cover prescription drug benefits, and states have flexibility in how they administer the Medicaid pharmacy benefit within federal guidelines about pricing and rebates. Under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), a manufacturer must enter into a rebate agreement with the Secretary of Health and Human Services, agreeing to rebate a specified portion of the Medicaid payment for the drug to the states and the federal government. In exchange, Medicaid programs cover nearly all of the manufacturer’s FDA-approved drugs, and the drugs are eligible for federal matching funds.

Biden-Harris: The Biden-Harris Administration enacted the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022, a major piece of legislation with a number of prescription drug provisions aimed at reducing federal drug spending, including allowing the federal government to negotiate prices for some drugs in Medicare and requiring that drug manufacturers pay rebates for price increases above inflation in Medicare. The latest proposed budget outlines steps to build on the IRA, including expanding the Medicare drug negotiation program. The administration also approved Florida’s plan to import some prescription drugs from Canada, though implementation is contingent on further action by Florida. Within Medicaid, the Biden-Harris Administration has taken action to strengthen the MDRP by lifting the rebate cap, and their latest budget proposal includes provisions to expand the MDRP and allow the federal government to negotiate for supplemental rebates on behalf of state Medicaid programs, though these provisions have not passed. The Biden-Harris Administration also issued a proposed rule (yet to be finalized) aimed at increasing price transparency and established a voluntary model to increase access to cell and gene therapies for people with Medicaid.

Trump and Republican Proposals: The Trump Administration encouraged states to submit waivers allowing states to create closed formularies, enabling Medicaid programs to negotiate directly with manufacturers for drug coverage (under current law, the MDRP creates an open formulary). The Trump Administration also created a new pathway to allow states to import prescription drugs from Canada, finalized a rule allowing manufacturers to report multiple best prices under value-based purchasing agreements with the goal of increasing value-based arrangements in the MDRP, and proposed lifting the rebate cap (this was later lifted by Biden-Harris Administration legislation). Both the RSC FY 2025 budget and Project 2025 seek to repeal the IRA, citing its impact on innovation and patient access, and Project 2025 proposes to address drug shortages by eliminating manufacturer rebate payments for multi-source generic drugs. Further, broader Republican proposals to cut and cap federal Medicaid spending could have implications for prescription drug coverage, as it is an optional benefit.

Tradeoffs: Recent Republican proposals take aim at the IRA while the Biden-Harris Administration plans to continue strengthening the IRA. KFF polling has found most voters are supportive of the Biden-Harris Administration proposals that build on the IRA. While the IRA is expected to lower prescription drug costs for people with Medicare and reduce drug spending by the federal government, the provisions do interact with the MDRP and could increase overall Medicaid prescription drug spending. Both administrations have taken action on drug importation, but, while the idea of importing prescription drugs has bipartisan support among the general public, there are long-standing concerns in terms of ensuring drug safety. The approach is also opposed by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) and the Canadian government and resulting savings estimates are unclear.

The Trump and Biden-Harris Administration records on the MDRP have diverged, with the Biden-Harris Administration working to strengthen the MDRP while the Trump Administration proposed allowing states to opt out of the program. While opting out of the MDRP could allow states to have more leverage when negotiating (because they could decide not to cover certain drugs completely), it is not clear that a closed formulary would result in savings, and closed formularies can restrict access to drugs for enrollees. Further, recent Republican proposals to address drug shortages and the late-era Trump Administration rule allowing multiple best price reporting could potentially weaken the MDRP and reduce the rebates states and the federal government receive from manufacturers. According to a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) study, rebates in the MDRP result in lower net drug prices in Medicaid compared with other federal programs.

Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS)

Context: LTSS encompass the broad range of paid and unpaid medical and personal care services that assist with the activities of daily living such as eating and bathing and the instrumental activities of daily living such as preparing meals and managing medication. They are provided to people who need such services because of aging, chronic illness, or disability and may be provided in institutional settings such as nursing facilities or in people’s homes and the community. Services provided in non-institutional settings are known as home and community-based services (HCBS), and those settings may include a person’s home, adult day care centers, assisted living settings, and group homes. Medicaid is the primary payer for LTSS, providing services to an estimated 1.4 million enrollees in nursing facilities and 4.5 million enrollees in HCBS settings.

Federal Medicaid statutes require states to cover nursing facility care and home health, but coverage of other LTSS is optional. Most HCBS are provided through “waivers,” which allow states to offer a wide range of benefits and to choose—and limit—the number of people who receive such services. Unlike other Medicaid services, many states use waiting lists when the number of people seeking services exceeds the number of waiver slots available. An estimated 0.7 million people have been on HCBS waiting lists in most years between 2016 and 2023. Medicaid has historically spent more money on LTSS in institutional settings than on LTSS delivered in home and community-based settings, but over the past decade, Medicaid has spent more on HCBS than institutional care due to states’ community integration obligations under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Supreme Court’s Olmstead decision. In Olmstead, the Supreme Court held that the unjustified institutionalization of people with disabilities is illegal discrimination and violates the Americans with Disabilities Act. A major challenge for Medicaid HCBS is finding enough workers, with employment levels in elderly care and nursing care facilities remaining below their pre-pandemic levels.

Biden-Harris: The Biden-Harris Administration increased federal financing for and oversight over Medicaid LTSS through increased funding, new legislative proposals, and rulemaking. The Administration enacted ARPA during the pandemic, which included a provision that temporarily increased the federal match rate for spending on Medicaid HCBS by 10 percentage points to expand access to HCBS and support direct care workers. The Biden-Harris Administration also issued legislative proposals calling for more permanent and extensive federal investments in Medicaid HCBS. The Biden-Harris Administration’s FY 2025 budget proposes further HCBS investment, requires the reporting of HCBS quality measures, and includes actions to further increase oversight of nursing facilities. The Administration also finalized several regulatory changes that would bolster Medicaid LTSS:

- Several rules aimed at combatting discrimination on the basis of disability, which may provide people with disabilities greater autonomy and independence while they receive Medicaid LTSS;

- Requirements for states to provide access to Medicaid HCBS, which includes ensuring payment rates are sufficient to support a workforce, reporting requirements related to waiting lists and other quality measures, and ensuring that 80% of Medicaid payments for certain HCBS are spent on compensation for direct care workers; and

- Establishment of the first ever requirements for minimum staffing levels in nursing facilities with increased transparency around the percent of Medicaid payments for institutional LTSS that are spent on workforce compensation and private equity ownership of nursing facilities.

Trump and Republican Proposals: The Trump Administration budgets and other Republican proposals do not include specific changes to Medicaid LTSS, but past policies and current proposals hint that services for older adults may be favored over people with disabilities who are under age 65. The Trump Administration’s regulatory actions generally resulted in less federal oversight over LTSS. The Trump Administration took actions to reduce federal oversight of Medicaid LTSS, including issuing a proposed rule that would have reduced federal requirements for nursing facilities (but was never finalized), suspending routine inspections in nursing facilities during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, and delaying requirements for states to comply with federal rules surrounding HCBS (the “HCBS Settings rule).” When COVID-19 vaccines became available, the Trump Administration launched the Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program to facilitate COVID-19 vaccinations in facilities where residents are ages 65 and older, though these initial federal vaccine programs did not cover settings that primarily serve people with disabilities under ages 65. Similarly, the 2024 Republican Party platform seeks to expand in-home care for older adults, but does not propose similar expansions for those with disabilities under age 65. It describes “shifting resources,” to support new policies to help seniors remain in their homes but does not specific what programs might be cut to free up such resources. Project 2025 includes language that would allow states “flexibility to redesign eligibility, financing, and service delivery of long-term care to serve the most vulnerable and truly needy and eliminate middle-income to upper-income Medicaid recipients,” which could include eliminating some of the optional Medicaid eligibility pathways that offer coverage to higher-income people who LTSS. Proposals that fundamentally change the financing structure of Medicaid such as cutting or capping federal spending would likely result in restrictions to LTSS.

Tradeoffs: The Biden-Harris Administration Medicaid LTSS policies could expand access to services and increase federal oversight of the quality of services provided but could increase spending on LTSS and reduce states’ flexibility in administering the Medicaid LTSS benefits. The Biden-Harris Administration has consistently called for legislative changes to provide additional funding for Medicaid LTSS (HCBS in particular).

In contrast, it is difficult to anticipate what specific proposals would emerge under a Trump Administration. The Trump Administration’s actions coupled with Republican proposals to eliminate the new nursing facility staffing standards and prohibit the requirement that 80% of Medicaid payments for certain HCBS are spent on compensation for direct care workers suggest that there would be less federal oversight of access to and quality of care, but more flexibility for states in providing Medicaid LTSS. Republican proposals support policies focusing on long-term care and helping seniors to remain in their homes but do not mention a role for Medicaid or home care for people under age 65, and nearly two thirds of people who use Medicaid HCBS are under age 65.

Managed Care

Context: States design and administer their own Medicaid programs within federal rules and determine how they will deliver and pay for care for Medicaid enrollees. Managed care is the dominant delivery system for Medicaid enrollees, with almost three-quarters of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in comprehensive managed care organizations (MCOs), accounting for about 52% of total Medicaid spending (or more than $415 billion) in FY 2022. State managed care contracts vary widely, in the populations required to enroll, the services covered (or “carved in”), and the quality and performance incentives and penalties employed. While there are federal and state requirements for managed care plans, plans have flexibility in certain areas, including in setting provider payment rates.

Managed care plans are at financial risk for the services covered under their contracts and receive a per member per month “capitation” payment for these services. To limit the amount that plans can spend on administration and keep as profit, CMS requires states to develop capitation rates for Medicaid to achieve a medical loss ratio (MLR) of at least 85%. The MLR reflects the proportion of total capitation payments received by an MCO spent on clinical services and quality improvement, where the remainder goes to administrative costs and profit. While there is no federal requirement for Medicaid plans to pay remittances to the state if they fail to meet the MLR standard, states have discretion to require remittances.

Biden-Harris: The Biden-Harris Administration released final Medicaid managed care regulations in 2024 aimed at improving access to care, quality, health outcomes, and health equity. The new rules establish national maximum wait time standards for certain appointments and a requirement for states to conduct independent secret shopper surveys to validate MCO compliance with wait time standards. The Biden-Harris Administration also finalized rules related to plan prior authorizations focused on streamlining process, reducing approval wait times, and improving transparency. The Biden-Harris Administration has taken action to improve Medicaid managed care monitoring, oversight, and transparency, releasing reporting templates and toolkits for states and publicly posting state managed care annual reports.

The Biden-Harris Administration enacted the 2024 Consolidated Appropriations Act, which included a financial incentive to encourage certain states to collect remittances from Medicaid MCOs that do not meet minimum MLR requirements. The Biden-Harris Administration’s FY 2024 and 2025 budgets went further proposing to require Medicaid managed care plans to meet an 85% minimum MLR and to require states to collect remittances if plans fail to meet the minimum MLR. The most recent budget also included provisions aimed at strengthening CMS’s Medicaid managed care financial oversight and compliance tools.

Trump and Republican Proposals: During his presidency, Trump took administrative action to change Medicaid managed care rules, including relaxing rules around network adequacy and beneficiary protections. Trump’s FY 2020 budget proposed changes to the Medicaid managed care waiver process (e.g., to lengthen the duration of certain managed care waivers) aimed at reducing administrative burden. Project 2025 notes the intent to reform and increase oversight of Medicaid managed care but doesn’t provide specifics. Proposals that fundamentally change the financing structure of Medicaid would likely also have implications for the delivery of care in Medicaid, impacting managed care plans.

Tradeoffs: Recent Democratic administrations have made sweeping changes to Medicaid managed care rules and regulations to advance program goals related to access to care, quality, fiscal and program integrity, beneficiary protections and support, and monitoring and oversight. However, establishing national standards and other state requirements can add state administrative burdens to come into compliance. The Biden-Harris Administration’s most recent budget proposed requiring Medicaid managed care plans to meet a minimum MLR of 85% (the statutory requirement for Medicare Advantage plans) and requiring states to collect remittances from plans if they fail to meet the required minimum (which would likely result in Medicaid savings)—to encourage plan investment in services and quality improvement and to prevent the retention of excessive profits.

The Trump Administration finalized changes to Medicaid managed care rules with chief goals that differed from Democratic administrations. The Trump Administration’s stated goals included reducing state and federal administrative burden, streamlining regulations, and promoting state flexibility and innovation in care delivery; however, tradeoffs could include fewer beneficiary protections, less oversight involving access to care, and variation in oversight across states.

Irving Washington

Irving Washington  Hagere Yilma

Hagere Yilma