The Mental Health Crisis Within the Mental Health Crisis

I remember meeting one evening many years ago with families of patients in one of our largest state psychiatric hospitals when I was Human Services Commissioner in New Jersey. I expected to see maybe 10 or 20 family members there that night, but hundreds came to express their frustration and outrage that more was not being done for their spouse, parent, child, or relative who was a patient there. They were concerned about the quality of care in the hospital and about the conditions in the facility, drug use, and safety. They were right to be worried. The facilities were old and badly understaffed, many of the patients were dumped there from the correctional system, which could not handle them or did not want to, about 70% of the patients had a substance use issue complicating chronic mental illness, and the psychiatric care provided to them was inadequate, to be kind. The families’ anguish was palpable and understandable. Many were in tears.

I remember meeting one evening many years ago with families of patients in one of our largest state psychiatric hospitals when I was Human Services Commissioner in New Jersey. I expected to see maybe 10 or 20 family members there that night, but hundreds came to express their frustration and outrage that more was not being done for their spouse, parent, child, or relative who was a patient there. They were concerned about the quality of care in the hospital and about the conditions in the facility, drug use, and safety. They were right to be worried. The facilities were old and badly understaffed, many of the patients were dumped there from the correctional system, which could not handle them or did not want to, about 70% of the patients had a substance use issue complicating chronic mental illness, and the psychiatric care provided to them was inadequate, to be kind. The families’ anguish was palpable and understandable. Many were in tears.

I was able to make some changes while in office, including improving staffing and closing an ancient and dangerous psychiatric facility for youth built in the late 1800s, but it was far from enough to satisfy me or those families. The legislature wasn’t much interested unless a patient escape made the front pages. Despite the tireless work of advocates and a few champions in the legislature, when it came time to allocate resources in the state budget, the chronically mentally ill wasn’t a funding priority. It was one of a few longstanding problems I likely could not fundamentally affect in a term in office in a large umbrella agency with seven other demanding divisions, including Medicaid and welfare. In government, you pick your shots. For me, then, the priorities were welfare reform, Medicaid managed care, school-based social services, homelessness, and of course inevitably, the crisis of the day or week.

That night, resigned to my limitations, I asked the press and staff to leave the room and met privately with the families. Near the end of the meeting, I gave them my personal phone number, feeling that if I could not make systemic changes, I had the authority to at least help individual cases. I heard from many of them, sometimes in the middle of the night when something went terribly wrong. I learned their stories. Sometimes we found a way to help individual cases, but even with control of a third of the state budget and workforce in the department, there was often little that could be done.

Decades later at KFF, we did a survey with CNN on mental health in America in 2022. Scrolling through our findings, headlines jumped off the page. Ninety percent of the public believed there was a crisis in mental health in America. Big numbers of people reported real problems accessing and paying for mental health services. Then they were there—the families. Somewhat buried in the survey was the story in data I had learned all those years ago in New Jersey: the mental health crisis isn’t just about patients with mental illness or the teens struggling with emotional problems or individuals coping with loneliness, it’s also deeply and centrally about families.

Any family with a family member experiencing mental illness knows all too well the serious stresses and strains that are part of the experience. But there was something else in the data that was even more striking: the number of families dealing with true crisis level events—a family member living on the street; making the brutal decision to institutionalize a loved one who is a threat to themselves or others; rushing a spouse or child to an ER with a drug overdose; self-harm; suicide attempts. And while we have inadequate services for families dealing with mental illness generally, we have even fewer services and supports for the families dealing with crisis events. The numbers of families experiencing a very serious mental health-related event is so large that it may constitute a crisis within the larger mental health crisis, and it’s one that does not receive enough attention.

Our Mental Health in America survey showed that these crisis events are pervasive and include many of the worst things that can happen in a family:

- Twenty-eight percent of all Americans say that their family had to take a painful step, like institutionalizing a family member because they were a threat to themselves or others.

- Twenty-one percent said they or a family member had a drug overdose requiring an ER visit.

- Fourteen percent said they or a family member ran away from home and lived on the streets due to mental health issues.

- Sixteen percent said a family member experienced homelessness because of a mental health problem.

- Eight percent said they or a family member had a severe eating disorder requiring hospitalization or in-person treatment.

- Twenty-six percent said they or a family member engaged in cutting or self-harm behaviors.

- And 16% had a family member who died from suicide.

When we looked at the overlap between the problems, half of American families (51%) experienced one or more of these severe crises. Let that sink in: half of all American families had a severe mental health-related crisis. It means that when you measure the impact of the mental health crisis, you really need to multiply manifold, something official statistics don’t do. These are the kinds of crises that truly challenge families. Parents and siblings struggle to deal with them and may never be the same after they occur. Often families make huge sacrifices to assist family members in crisis.

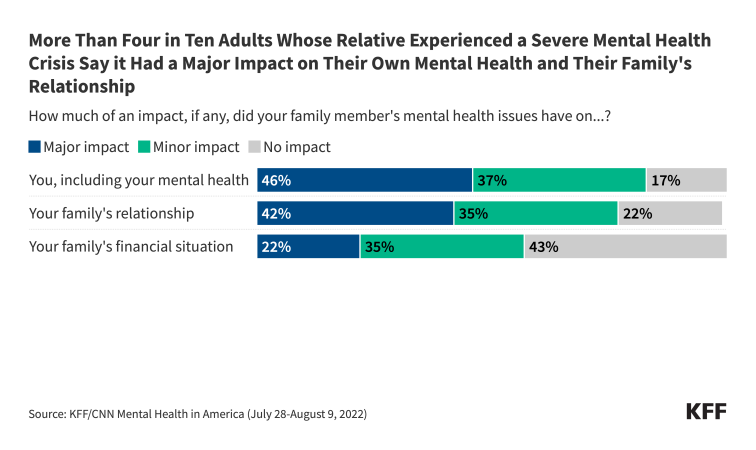

The survey data show some of the consequences. Over four in ten say the crisis had a major impact on their own mental health or their family’s relationships. One in five say it had a major impact on the family’s financial situation. This group, which has the most direct experience with mental health care in this country, are more likely to believe that mental health issues in both children and adults are at a crisis level in the U.S., and that most people are not able to get the mental health services they need.

Not surprisingly, every bad outcome is complicated by poverty, and family crises like these are more likely to occur in lower income households. Fifty-seven percent of people living in households earning less than $40,000 a year experienced these crises compared with 43% of those in families earning more than $90,000.

Some adults know or can figure out who to call if a family member needs help with a serious mental health-related problem, such as a drug problem or a potential suicide. Local and national crisis hotlines are sometimes available for different problems. But how many know who to call for a family fraying and in crisis? How many would be afraid to call for fear of alerting law enforcement or child protective services to some problems? Sometimes, of course, dysfunction or something worse in a family contributes to a family member’s problem or even is the problem, further complicating solutions.

NAMI, the national organization representing families with mental illness, does valiant work through its chapters providing support and advocacy, but it can only do so much and cannot manufacture services that do not exist for a family dealing with a crisis.

Ultimately, the best thing we can do for families experiencing a mental health related crisis is to more effectively address the underlying problem affecting their family member. In my next column, I will review the problems Americans have accessing mental health services.

There wasn’t a great deal I could do on the spot for those families at the psychiatric hospital in New Jersey back then. But the data are a reminder of how the mental health crisis in America affects families as well as individuals, magnifying its impact, expanding the policies and services needed to address it, and changing the way we need to think about the problem.