DMPA Contraceptive Injection: Use and Coverage

The DMPA contraceptive injection is a commonly used reversible contraceptive method among women in the United States. Also known as the “shot,” the injection is commonly known by its brand-name Depo Provera (depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate or DMPA), although generic alternatives are now available. It was first introduced in the United States in 1959 for management of menstruation and was approved for contraceptive use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1992. This factsheet provides an overview of the types of contraceptive injection, use, awareness, availability, and insurance coverage of the injection in the U.S.

How does the DMPA work?

The shot works by releasing the hormone DMPA, a progestin, which suppresses ovulation and thickens cervical mucus that also helps keep sperm from fertilizing an egg. DMPA can be provided by an intramuscular shot administered by a clinician or by a subcutaneous shot that can be injected by the patient at home. Both forms need to administered once every 12 weeks to be effective. Brand-name Depo-Provera and the generic equivalents for medroxyprogesterone acetate are intramuscular injections, providing 400mg of progestin in one dose. The Depo-subQ Provera 104 injection uses a smaller needle and a lower dose of progestin (104 mg) than the intramuscular alternative. Because Depo-subQ Provera 104 uses a smaller needle, it can be less painful than the intramuscular injection and can be administered by the patient at home, while having the same contraceptive effectiveness.1 Like most contraceptives, the DMPA shot does not protect against STDs; use of condoms are recommended to reduce the risk for STDs, including HIV while using DMPA shots.

The DMPA shot has a typical use failure rate of 4% when used once every three months. Contraceptive methods such as implants, intrauterine devices (IUDs), vasectomies, and tubal ligations are typically more effective than the shot, because these methods involve little to no follow-up care, while injections need to be repeated every 12 weeks in order to be effective. Condoms or another non-hormonal contraceptive are recommended as a back-up for 7 days after the first injection. If a patient is more than 4 weeks late for a shot (16 weeks after their last shot), it is recommended that she take a pregnancy test before the next dose and that she use condoms or another non-hormonal contraceptive as a back-up for another 7 days if she receives another shot .2 It takes an average of 10 months for pregnancy to occur after stopping the injection, which is comparable to other methods such as the IUD and pill.3

The DMPA shot has several non-contraceptive benefits, but also has some side effects and risks. Benefits include lower risk of uterine cancer and reduced symptoms of endometriosis. However, among contraceptives used in the U.S., the injectable has the highest discontinuation rate, associated with side effects, which include menstrual irregularities (spotting or cessation of periods) and weight gain. Of note, Depo-Provera comes with a black box warning from the FDA that the contraceptive injection should not be used as a long-term (longer than 2 years) method unless other contraceptive methods are considered inadequate, as women who use Depo-Provera may lose significant bone density. However, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the World Health Organization (WHO) disagree with this warning, stating that loss in bone density from DMPA is not associated with fractures and appears to be reversible after discontinuation of the injectable. Both organizations conclude that the benefits of DPMA use outweigh the theoretical fracture risk, and that DMPA may be prescribed without limitations on its duration of use.

Use, Awareness, and Availability of the Contraceptive injection

Approximately, 2.3% of women who use contraception report that they use the contraceptive injection. Over the last two decades, women’s access to and options of various contraceptive choices have changed, and overall use of the injection has declined, as more women are using long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), such as IUDs and implants.

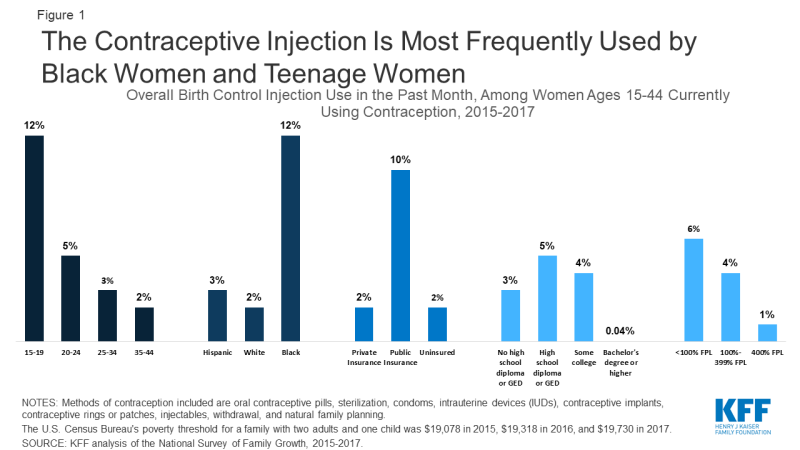

Among reproductive age women who use any form of contraception, the contraceptive injection is most often used by young women, lower-income women, and Black women. Use of the injection also decreases with educational attainment – those with bachelor’s degrees are far less likely to use the shot as their contraceptive method (Figure 1).

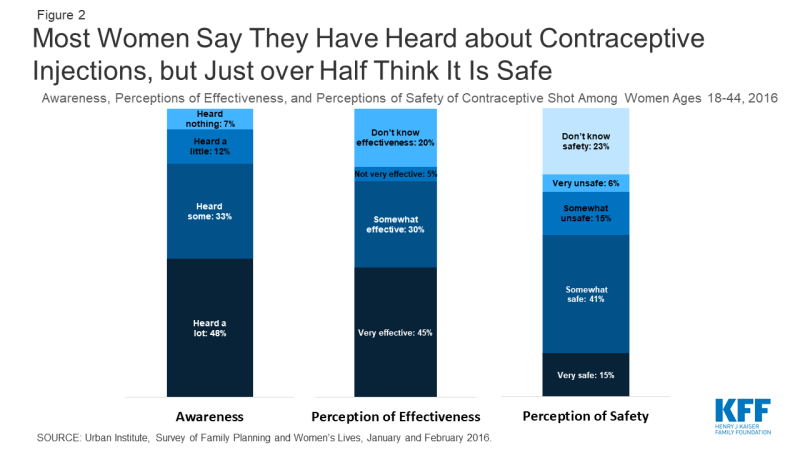

In a 2016 Urban Institute study of reproductive age women, 81% had heard some or a lot about the contraceptive shot, while about one in five had heard just a little or nothing at all. This was comparable to awareness of other major hormonal contraceptives, including the pill and IUD. The same study surveyed perceptions of effectiveness and safety of various contraceptive methods, finding that 75% of reproductive age women thought the shot was somewhat or very effective and more than half (56%) found the shot to be somewhat or very safe (Figure 2). However, about a fifth of women said that they did not know whether the injection is effective (20%) or safe (23%).

Figure 2: Most Women Say They Have Heard about Contraceptive Injections, but Just over Half Think It Is Safe

Insurance Coverage and Cost of the Contraceptive Injection

As of 2011, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has required most private insurance plans and Medicaid expansion programs to cover one of each of the 18 FDA approved contraceptive methods without cost sharing. Women with private insurance and those eligible for the Medicaid expansion, are eligible for patient education, counseling, and access to at least one form of the contraceptive injection without cost sharing, the visit, discontinuation and management of side effects. This includes at least one form of the injection, but plans may not cover both the intramuscular formulation and Depo-subQ Provera 104; however, if a clinician determines that a particular injectable formulation is medically appropriate for a patient then the plan must cover that form.

For those without insurance there are potentially two fees for patients getting the contraceptive injection: the first doctor’s visit, and the follow up injections. The office visit for the prescription ranges on average from $50-$200, with additional injections averaging $20-$40. Many clinicians, both private practice as well as at safety-net clinics, provide and administer the contraceptive injection. Safety-net clinics that participate in the Federal Title X family planning program may charge uninsured women on a sliding scale and may forego charges for those on the lowest end of the income scale. The Office of Population Affairs (OPA) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) reported that, in 2018, nearly 475,000 women received the DMPA injection as their primary contraceptive method a from a Title X service provider.

In 11 states (CA, CO, HI, ID, MD, NM, NH, OR, TN, UT, WV) and the District of Columbia, pharmacists can provide hormonal contraceptives directly to women, including the intramuscular contraceptive shot without the need to first visit a physician to obtain the injection.4 However, pharmacist participation in the program is not required and has been low in some states. Furthermore, while the actual DMPA shot may be covered, women may have to pay some cost out of pocket because there may be a charge for the pharmacist consultation, which is not required to be covered under the contraceptive coverage policy in most of these states.5

Endnotes

Sobel L et.al, Kaiser Family Foundation and The Lewin Group, Coverage of Contraceptive Services: A Review of Health Insurance Plans in 5 States, April 2015.

Reproductive Health Access Project, Factsheet: The Shot/Depo-Provera, July 2015.

It takes patients an average of 10 months to get pregnant after their last injection, but an average of 7 months after the effects of the shot have worn off. This is in line with other contraceptive methods, such as an IUD, pill, or implant. Girum T, Wasie A, Return to fertility after discontinuation of contraception: a systematic review and meta-analysis, July 2018.

Rafie S et.al, Pharmacists’ Perspectives on Prescribing and Expanding Access to Hormonal Contraception in Pharmacies in the United States, August 2019.

The cost for a pharmacist consult is required to be covered in Hawaii, Tennessee, and for Medicaid beneficiaries in Oregon.