Tax Subsidies for Private Health Insurance

II. Non-Group Coverage

Unless they are eligible for public coverage, people who are not offered health insurance from an employer must seek individual health insurance, sometimes known as non-group coverage. The ACA instituted significant reforms to the non-group market, including establishing state and federal marketplaces where individuals can shop and purchase coverage. Starting in 2014, qualifying households are able to receive premium tax credits to purchase discounted coverage on the exchanges. In addition to tax credits, existing law allows households to deduct certain medical expenses from their taxes, including the cost of health insurance premiums. The tax benefits for non-group coverage are structured progressively, with greater relief for lower-income households. This section first examines the value of tax-deduction for non-group plans before looking at examples of households who receive the tax-deduction and a premium tax credit.

Federal Tax Deduction for Medical Expenses

Families that itemize their deductions can deduct the portion of their medical expenses, including health insurance premiums that exceed 10% of their adjusted gross income.1 A wide variety of medical expenses qualify for this deduction including: out-of-pocket expenses, such as acupuncture, ambulance services, and smoking cessation programs, as well as insurance premiums. So, even if a family purchases a health insurance plan with a low premium, they may still claim the deduction if they incur other health care costs exceeding the 10% threshold. The ACA increased the income threshold at which households could claim medical expenses in two ways. First, the threshold was increased for non-elderly families, from 7.5% to 10% of income. For example, a household earning $100,000 can now deduct expenses greater than $10,000 a year as opposed to $7,500. Secondly, elderly families also have to meet the 10% threshold when their income is high enough to invoke the alternative minimum tax.

There are two important limitations associated with the medical expense deduction. The first is that it is only available to families who itemize their deductions. Families generally itemize their deductions when the amount of itemized deductions exceeds the standard deduction otherwise available to tax filers. In 2012 the standard deduction amounts were $5,950 for people who were single or married couples filing separate tax returns, $11,900 for married couples filing a joint tax return (or certain widowers with dependent children), and $8,700 for people filing as head of a household.2 Federal tax law permits itemized deductions for a number of different expenses, including medical and dental expenses, certain state and local taxes paid by the family, real estate and property taxes, interest on a home mortgage loan (and other home mortgage expenses), charitable gifts, casualty and theft losses, and certain business expenses. Families that pay mortgage interest, for example, are likely to benefit from itemizing their deductions, and may then be able to deduct a portion of their non-group health insurance premiums as well. The percentage of households who itemize deductions increases with a household’s income; 22% of households with adjusted income between $20,000 and $50,000 itemize their deductions, compared to 55% of households between $50,000 and $100,000, and 84% of households between $100,000 and $200,000.3

The second limitation is that the medical and dental expense deduction is limited to expenses that exceed 10% of adjusted gross income for non-elderly households. If the only medical expense for a family earning $80,000 was a $12,500 family non-group premium, the family could deduct $4,500 of the premium ($12,500 premium minus 10% of the $80,000 income, or $8,000). The amount of the tax deduction would depend on the family’s marginal income tax rate, which would be largely determined by the amount of their other deductions. Note, a family with $80,000 of adjusted gross income who opts for a lower, non-group premium of $8,000 could not take a deduction in this case, because 10% of their adjusted gross income ($8,000) is equivalent to the premium amount. Families with higher incomes are unlikely to be able to take a deduction for their non-group premiums unless they have significant amounts of other medical expenses, or purchase an expensive policy.

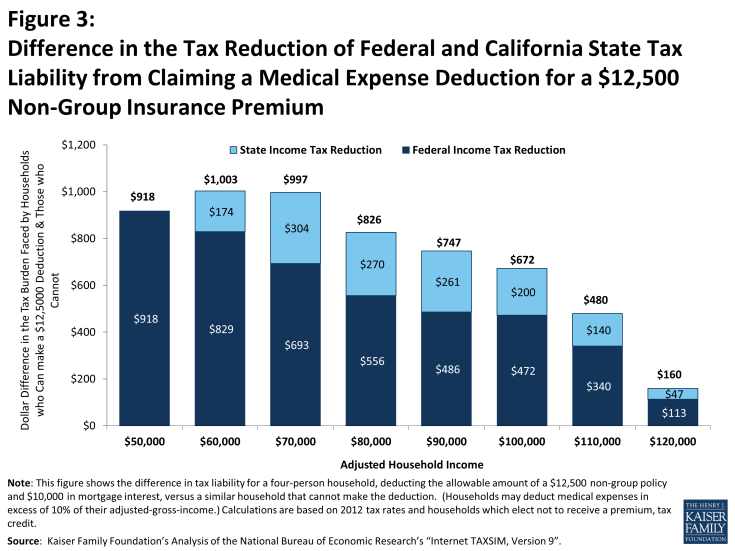

Figure 3 shows examples of how the medical expense deduction could work for families with different incomes. The example shows families with different levels of wage income and no other income, similar to the examples above, but these families do not have ESI and do not receive tax credits authorized under the ACA. The families are assumed to purchase a non-group health insurance policy with an annual premium of $12,500, and have no other medical or dental expenses to deduct. To ensure that the families have sufficient deductions to itemize, we also assume that the families pay $10,000 in mortgage interest and take deductions for state taxes (the amounts deducted vary with income and are calculated through the TAXSIM model). We are comparing families who can take the tax deduction versus similarly-earning families who do not. So, for families who can take the deduction, we first deduct the portion of the $12,500 premium that exceeds 10% of their adjusted gross income and then use the model to calculate federal and state income tax liabilities. The differences in tax reductions for these families are shown in the Figure 3.4 A family with an income of $60,000 will owe $1,003 less in taxes than a family earning the same income who does not take the deduction. A family with $100,000 of income will only save $672 in taxes compared to its counterpart.

Figure 3: Difference in the Tax Reduction of Federal and California State Tax Liability from Claiming a Medical Expense Deduction for a $12,500 Non-Group Insurance Premium

The tax deduction has a smaller impact for higher income households, because they can deduct a smaller portion of their medical expenses. In our example, the family with $60,000 of income can deducted $6,500 of the premium while the household earning $100,000 can only deduct $2,500. Partially offsetting the impact of falling deduction amounts is that the marginal tax rates increase with income, so families at higher incomes save a larger share of the smaller amount that they can deduct (see Table 3). For example, the family at $50,000 can deduct $7,500, but because their tax rate is relatively low, their federal savings are only about 15% of their deduction. In contrast, the family at $100,000 can deduct only $2,500, but their federal tax reduction is about 25% of the amount deducted. It is important to note that this medical expense deduction is an income tax deduction which, unlike the tax exclusion for ESI discussed above, works only to reduce income tax liability and not the amount of FICA taxes paid.

Premium Tax Credits for Non-Group Coverage

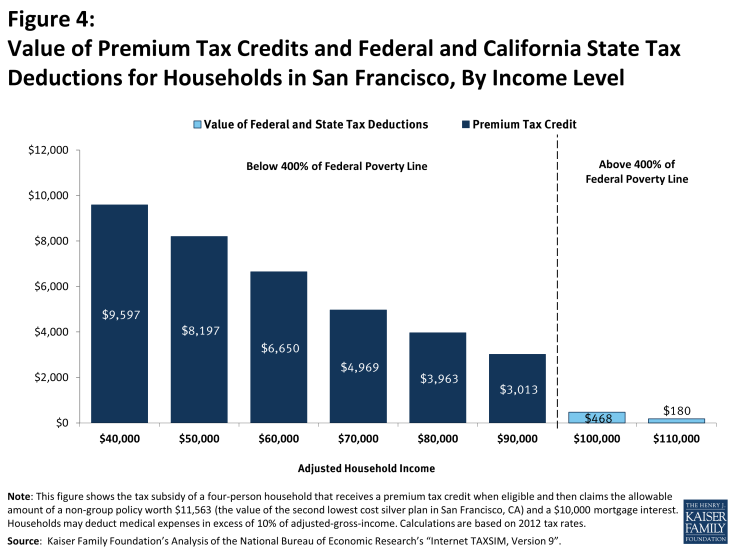

The establishment of tax credits for non-group coverage has meaningfully changed the tax incentives for households purchasing non-group coverage. Starting in 2014, low-income households without an offer of employer coverage and incomes between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level will be eligible for tax credits for qualifying non-group coverage on health insurance exchanges. Tax credits will be assessed on a sliding scale, with higher income families’ receiving a smaller credit than households with more modest incomes. Households between 100% and 250% of the federal poverty line may qualify for additional tax credits designed to lower the cost sharing required for the plan they choose. Premium subsidies are structured so households with incomes beneath 400% of poverty are not required to contribute more than 9.5% of their income to purchase a silver plan (a plan that covers on average 70% of the cost of health benefits)5. This provision means that fewer households will be able to take advantage of the tax deduction of medical expenses without incurring out-of-pocket expenses. Families may elect to purchase a higher cost, gold or platinum plan, which could increase their premium contribution above the 10% threshold. Figure 4 looks at the premium tax credits and tax deductions available to example households in San Francisco.

Figure 4: Value of Premium Tax Credits and Federal and California State Tax Deductions for Households in San Francisco, By Income Level

San Francisco is a relatively high cost area. The second lowest-cost silver plan, which covers roughly 70% of an average enrollees’ expenses, is valued at $11,563 for a non-smoking couple with two children. Households earning between $40,000 and $90,000 in income qualify for subsidies ranging from $9,597 to $3,013 a year. The tax credits lowered the medical spending for the example households with incomes between $40,000 and $90,000 below the 10% threshold required to deduct expenses. For example, a household with an income of $40,000, premium costs of $11,563, and a tax credit of $9,597 has medical expenditures equivalent to 4.9% of the total income ($1,966 in medical expenses, assuming no other medical expenses are made). The premium tax credits available on health insurance exchange provide a much higher tax subsidy to households than they would have been able to receive before 2014. An example household with an income of $60,000 who purchase non-group coverage without a premium tax credit could receive a $1,003 worth of tax deductions (figure 3) whereas the example household who purchase a plan on the health insurance exchange can receive a tax credit of $6,650 (figure 4).

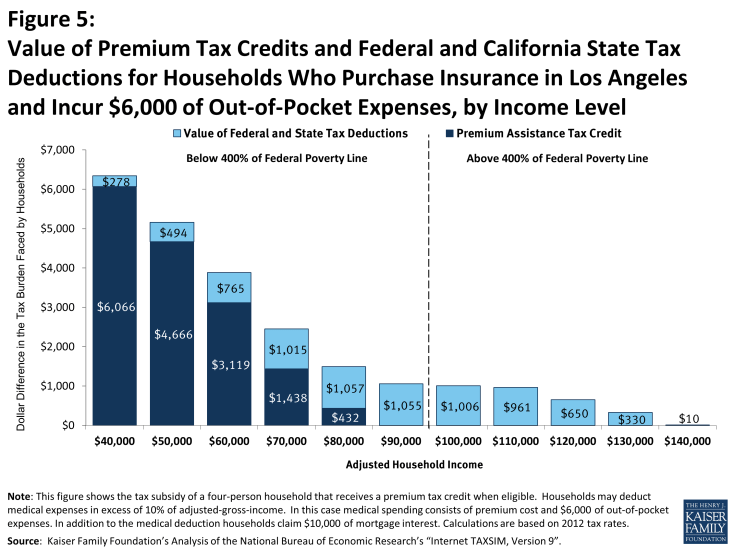

Figure 5: Value of Premium Tax Credits and Federal and California State Tax Deductions for Households Who Purchase Insurance in Los Angeles and Incur $6,000 of Out-of-Pocket Expenses, by Income Level

Households making between $100,000 and $110,000 dollars a year earn too much to qualify for premium assistance tax credits but have incomes low enough that at least part of their premium can be deducted.6 Households earning $120,000 or more a year are not eligible to deduct any medical expense unless they incur other out-of-pocket medical expenses.

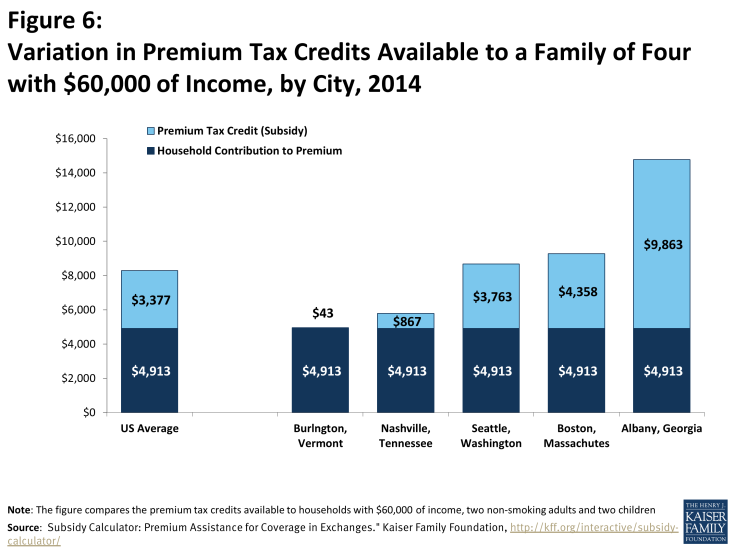

The tax credits available on the health insurance exchange vary in important ways other than income. In many parts of the country, health insurance premiums are less than in San Francisco; in cases in which the premium is less than $10,000, no household will be able to deduct any of the cost of the premium unless they have other out-of-pocket expenses. Since premium tax credits limit the amount of a household’s income they are required to spend on coverage, households in areas with higher premiums receive a larger tax credit. Figure 6 shows examples of regional variation for the same four person family earning $60,000 dollars in different cities.

Figure 6: Variation in Premium Tax Credits Available to a Family of Four with $60,000 of Income, by City, 2014

Examples with Premium Tax Credits And Medical Deductions

Many non-group plans require considerable cost-sharing from enrollees. Households who incur out-of-pocket expenses may receive both a premium tax credit and deduct medical expenses. For example, we calculated the tax burden of households who purchased coverage in Los Angeles and have $6,000 dollars of out-of-pocket medical expenses, such as deductibles or copayments.7 The second lowest cost silver premium is less expensive than in San Francisco, costing a non-smoking couple with two kids $8,032. Table 4, illustrates the amount that households are able to deduct by income level; for example the household with a $100,000 of income can deduct 4,032, which accounts for the value of their premium ($8,032) plus the value of their out of pocket spending ($6,000). The example households with incomes between $40,000 and $80,000 qualified for the premium assistance tax credits on the health insurance exchanges. While the example household with $90,000 earns less than 400% of the federal poverty line, the total cost of the premium does not exceed 9.5% of their household income and they therefore do not qualify for a premium assistance tax credit. All of the example households below 400% of poverty are able to deduct medical expenses ranging from $3,965 to $5,032; in each case, these households’ contributions to the insurance premium in addition to their out-of-pocket expenses exceeded 10% of their income. While households between $90,000 and $140,000 dollars are not eligible for a premium assistance tax credit they are able to deduct the portion of their medical spending that exceeded 10% of their income.

| Table 4 | ||||

| Individual Premium Contribution (value of premium – premium assistance tax credit) |

Assumed Out-of-Pocket Spending | Medical Spending (premium contribution + out-of-pocket spending) | Deductible Medical Spending (Medical Spending -10% of Income) |

|

| $40,000 | 1,965 | 6,000 | 7,965 | 3,965 |

| $50,000 | 3,365 | 6,000 | 9,365 | 4,365 |

| $60,000 | 4,913 | 6,000 | 10,913 | 4,913 |

| $70,000 | 6,594 | 6,000 | 12,594 | 5,594 |

| $80,000 | 7,600 | 6,000 | 13,600 | 5,600 |

| $90,000 | 8,032 | 6,000 | 14,032 | 5,032 |

| $100,000 | 8,032 | 6,000 | 14,032 | 4,032 |

| $110,000 | 8,032 | 6,000 | 14,032 | 3,032 |

| $120,000 | 8,032 | 6,000 | 14,032 | 2,032 |

| $130,000 | 8,032 | 6,000 | 14,032 | 1,032 |

| $140,000 | 8,032 | 6,000 | 14,032 | 32 |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, “Analysis of Subsidy Calculator: Premium Assistance for Coverage in Exchanges.” Kaiser Family Foundation, n.d. Web. 21 Mar. 2014. https://www.kff.org/interactive/subsidy-calculator/. | ||||

Given the high cost sharing in plans being offered on the exchanges, many households receiving premium tax credits will face considerable out-of-pocket spending if they use services. The medical spending deduction will continue to provide tax relief to these households. The combination of premium tax credits and the medical deduction provide a larger tax subsidy to lower income households’ families. The example households who receive smaller premium tax credits (those with incomes between 300% and 400% of federal poverty) received the most benefit from the medical deduction.