Modern Era Medicaid: Findings from a 50-State Survey of Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Policies in Medicaid and CHIP as of January 2015

Enrollment and Renewal Processes

The ACA enacted sweeping changes to transform application, enrollment, and renewal processes in Medicaid and CHIP and coordinate with the new Marketplaces. Together these processes are intended to achieve the ACA’s vision to provide “no wrong door” access to all health coverage options, minimize the paperwork burden on consumers and state agencies, and enhance the consumer experience. Specifically, under the ACA, states must provide multiple options for individuals to apply for health coverage, including online, by phone, by mail, and in person, using a single streamlined application for Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace coverage. In addition, states must seek to rely on electronic data to verify eligibility criteria and renew coverage based on electronic data matches. Adoption of these procedures represents major modernization in many states that previously had relied on antiquated, paper-based enrollment processes for Medicaid and CHIP. States have achieved significant progress adopting many of these processes, but work continues in many areas.

Applications

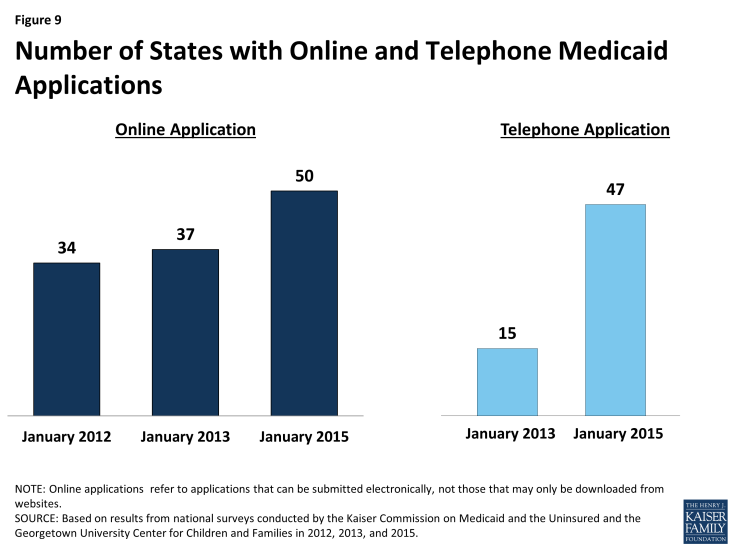

As of January 1, 2015, individuals can apply online for Medicaid at the state level in all states, except Tennessee. Most states with a State-based Marketplace (SBM) (12 of 17) provide a single integrated online application portal for Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. All states relying on the Federally-facilitated Marketplace (FFM) for Marketplace eligibility and enrollment functions maintain their own online Medicaid application separate from Healthcare.gov, as required, except Tennessee, where individuals can only apply online for Medicaid through Healthcare.gov. In about half of all states (25), an online multi-benefit application is available that allows individuals to apply simultaneously for Medicaid and other benefits, such as SNAP or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). The availability of an online Medicaid application in nearly all states represents substantial progress from just several years ago; an online option was available in only two-thirds of states (34) as of January 2012 and 37 states as of January 2013 (Figure 9).

The majority of states are accepting Medicaid applications by phone as of January 1, 2015. Medicaid applications can be submitted by telephone at the state level in most states (47) either through the Medicaid agency or the SBM call center, but work continues in the remaining states to support phone-based applications. The broad availability of a telephone application across states also represents marked progress among states in modernizing enrollment processes as only 15 provided this option as of January 2013.

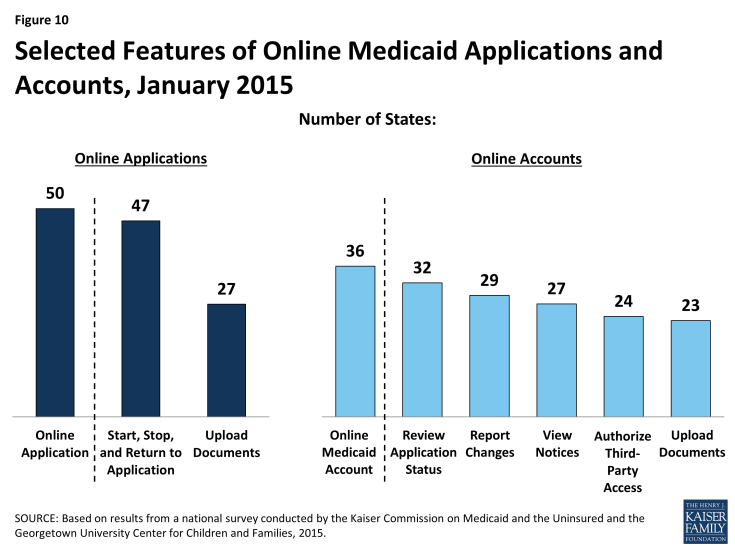

There is variation across states in the functions of online applications and the availability and features of online Medicaid accounts. In most states (47), applicants can start, stop, and return to the online application, and, in just over half of states (27), the online application provides applicants the ability to upload electronic copies of documentation if it is required (Figure 10). More than two-thirds of states (36) also provide individuals the opportunity to create an online account for ongoing management of their Medicaid coverage, which may include the ability to review the status of their application (32 states), report changes (29 states), view notices (27 states), authorize third-party access (24 states), and upload documentation (23 states). Many of these states plan to add capabilities over time and additional states plan to add online accounts in 2015 or beyond.

Verification of Eligibility Criteria

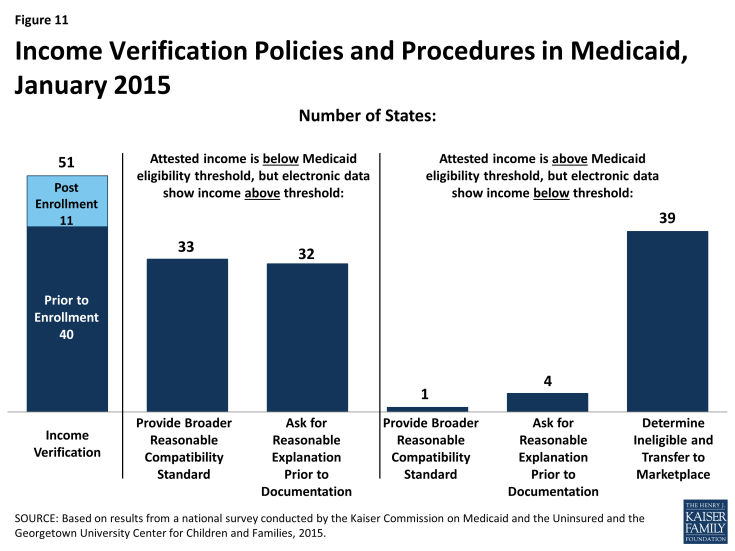

All states are developing their capacities to tap electronic data sources to verify incomes of Medicaid and CHIP applicants, as required by the ACA. States must verify income using electronic data sources to the extent possible. Forty states confirm applicants’ income prior to enrollment, while 11 states process eligibility based on an applicant’s attestation and verify after enrollment (Figure 11). To facilitate electronic verification, a federal data hub was established that allows states to access information from multiple federal agencies, including the Internal Revenue Service, the Social Security Administration, and the Department of Homeland Security. In addition, states can access other databases that collect state wage information, unemployment compensation, vital statistics, and eligibility for other public programs. Verifying eligibility elements is not only technically complicated, but also requires the establishment of data sharing agreements between agencies that protect the privacy and security of personally identifiable information. These challenges can slow state progress in accessing electronic data sources on a timely basis to verify eligibility. Looking ahead, states are continuing to enhance their data matching capabilities.

Over half of states have opted to set a broader “reasonable compatibility standard” than required to address cases in which there are differences between self-reported income and data from electronic sources. Federal rules require states to disregard differences between self-reported income and an electronic data source if the difference does not affect eligibility (i.e., both are at, above, or below the Medicaid or CHIP eligibility threshold). Thirty-three states have taken up an option to establish a broader reasonable compatibility standard for cases in which self-attested income is below but electronic data sources show income above the Medicaid or CHIP eligibility limit. If the difference is within this reasonable compatibility standard, which is most often 10 percent, the self-reported income is accepted. Regardless of whether they have set a broader reasonable compatibility standard, if data are not reasonably compatible, states may accept a reasonable explanation of the difference (e.g., the individual lost a job) before requiring paper documentation, which 32 states do. Only one state (New Jersey) provides a broader reasonable compatibility standard for cases in which self-reported income is above the Medicaid or CHIP income threshold and electronic data sources show income below the threshold. In these circumstances, most states (39) determine the individual ineligible for Medicaid or CHIP and transfer the account to the Marketplace for determination of eligibility for subsidies.

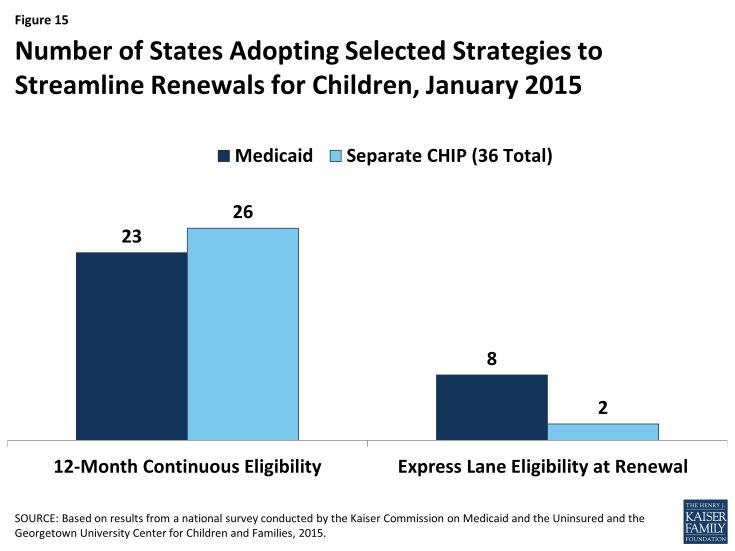

Many states minimize burdens for applicants and states by relying on self-attestation of non-financial eligibility criteria. As is the case with income, states must verify citizenship and immigration status for new applicants through electronic data sources. However, states have additional options to verify other non-financial eligibility criteria, including age/date of birth, state residency, and household composition. For these criteria, states can either verify pre- or post-enrollment or accept self-attestation. Many states accept self–attestation of age/date of birth (21), state residency (35), or household size (39), although verification is required if a state has any conflicting information on file (Figure 12). The remaining states confirm these eligibility criteria prior to enrollment or post enrollment, although most do not verify the information at renewal. Accepting self-attestation simplifies the enrollment process for states and applicants, and past experience shows that reducing paperwork burdens boosts enrollment and retention.1 Historically, some states have been reluctant to minimize documentation requirements due to concerns about penalties associated with inaccurate eligibility determinations. However, moving forward, audits of state eligibility determinations will focus on validating that states’ systems and processes are consistent with the verification plans they must submit to CMS that outline their policies for determining eligibility.

Figure 12: Non-Financial Verification Procedures Used by Medicaid Agencies at Application, January 2015

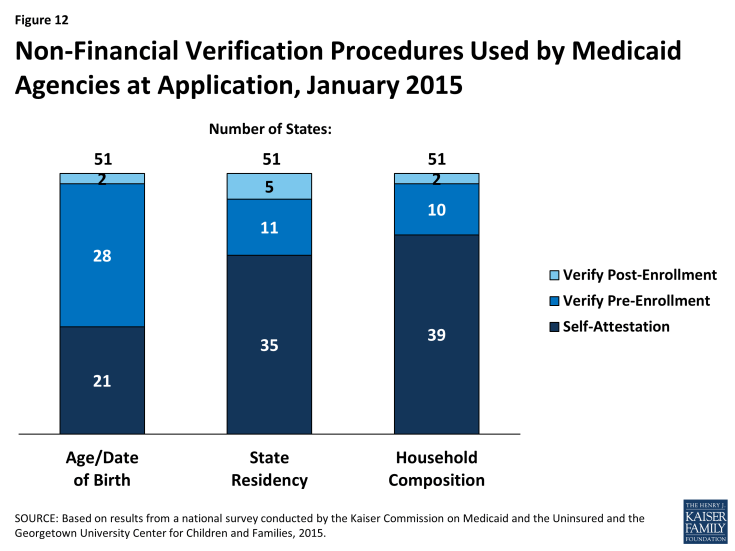

Facilitated Enrollment Options

A range of additional streamlining options further facilitate enrollment of eligible individuals in some states. Under the longstanding presumptive eligibility option in Medicaid and CHIP, states can allow qualified entities to expedite access to coverage for children and pregnant women. The ACA allows states to expand this option to parents and other adults if the state offers it to children or pregnant women. States have taken mixed action with regard to providing presumptive eligibility. Since 2013, several states have eliminated presumptive eligibility for children (MA, MI and UT) or pregnant women (AR, DE, MA, MI, and OK), likely given that new data-driven enrollment processes are designed to enable faster eligibility determinations. Conversely, five states (ID, MT, NH, NJ and OH) have expanded presumptive eligibility to parents or other adults. Following this state action, as of January 2015, 15 states provide presumptive eligibility for children in Medicaid, 9 for children in CHIP, 27 for pregnant women, and 5 for adults (Figure 13). The ACA also establishes new authority for hospitals to conduct presumptive eligibility determinations, although states are in various stages of effecting this requirement. In addition, since 2009, states have had the option to utilize Express Lane Eligibility (ELE) to enroll children in Medicaid or CHIP based on eligibility findings from other programs, like SNAP. As of January 1, 2015, nine states use ELE to enroll children in Medicaid, while five use ELE to enroll CHIP-eligible children. In 2013, CMS offered states additional facilitated enrollment options, including using SNAP data to identify and enroll eligible individuals and using child enrollment data to expedite parent enrollment. To date, eight states have taken up one or both of these strategies, which analysis has shown contributed to success in enrolling newly eligible adults and children and reducing administrative costs.2 These options remain available for other states to take up moving forward.

Figure 13: Number of States Adopting Targeted Strategies to Streamline Enrollment of Eligible Individuals, January 2015

Renewal

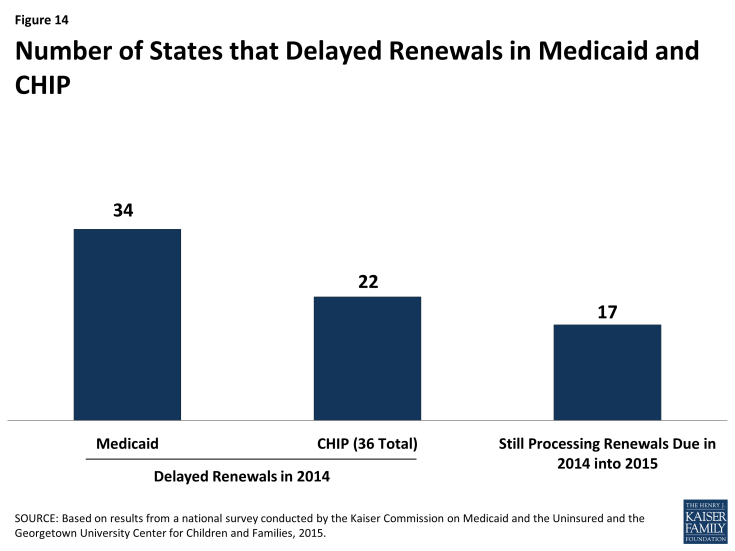

States are making progress adopting automated renewal processes, but transition work continues. Similar to enrollment processes, the ACA calls for new highly automated, paperless renewal processes for Medicaid and CHIP. When possible, states must use available data to renew coverage automatically (also called ex parte renewal). Many states are still implementing and transitioning to these new processes, given a range of challenges including developing system capacity to process automated renewals, transferring data for existing enrollees from old legacy systems to new systems, and creating notices for individuals. In the interim, a number of states are relying on mitigation strategies such as mailing forms to individuals to request the information needed to complete renewal. To ease the transition to new renewal procedures, CMS offered states the opportunity to temporarily delay renewals, an option which 34 states took up for Medicaid and 22 states took up in CHIP during 2014 (Figure 14). About half have completed all of their delayed renewals, although 17 states have extended some of these renewals into 2015. Continued work to address the challenges of adopting new automated renewal processes will be important for preventing coverage losses and gaps and supporting more stable coverage over time.

In July 2014, CMS offered states additional flexible renewal strategies. CMS clarified that states can continue to conduct renewals based on available information without collecting the additional information necessary to coordinate with Marketplace coverage, which includes tax-filing status and access to employer coverage. However, states can only affirmatively renew coverage using this approach and cannot deny coverage without collecting all required information. Additionally, states can receive expedited waiver approval from CMS to renew coverage using information from SNAP, as well as to facilitate renewals for enrollees with no change in circumstances that affect eligibility.

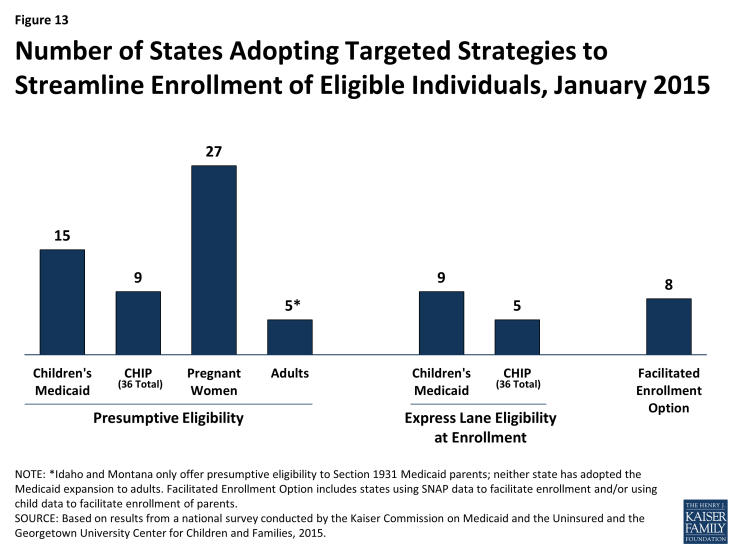

Some states are utilizing other policy options to boost retention and support stable coverage over time. Under the ACA, all states must conduct renewals once every 12 months. States can further support stable coverage and reduce churn resulting from small fluctuations in income by opting to provide 12-month continuous eligibility, which allows individuals to remain enrolled for a full year regardless of changes in circumstances. As of January 1, 2015, 23 states provide 12-month continuous eligibility to children in Medicaid, and 26 have adopted it in their separate CHIP programs (Figure 15). States also can extend 12-month continuous eligibility to parents and other adults under Section 1115 waiver authority, which New York has done for parents to provide consistent procedures for all enrolled family members. Another option available to states to streamline renewal is ELE, which eight states use to renew children’s Medicaid coverage and two states utilize for CHIP renewals. Massachusetts is also using ELE to renew parents in Medicaid under Section 1115 waiver authority.