Medicare Part D at Ten Years: The 2015 Marketplace and Key Trends, 2006-2015

Section 3: Part D Benefit Design and Cost Sharing

Plan Benefit Design

Most Part D plans do not offer the defined standard benefit (with a $320 deductible in 2015 and 25 percent coinsurance); all PDPs and most MA-PD plans have a tiered cost-sharing structure with incentives for enrollees to use less expensive generic and preferred brand-name drugs. For the first time in 2015, no PDPs offer the defined standard benefit without formulary tiers. Among MA-PD plans, 2 percent offer the defined standard benefit with 1 percent of enrollment.1

A majority of Part D enrollees are in enhanced plans. In 2015, 53 percent of all Part D enrollees are in enhanced plans, designed to offer some benefits beyond the basic benefits defined in law. Nearly half (45 percent) of PDP enrollees and 72 percent of MA-PD enrollees are in enhanced plans.

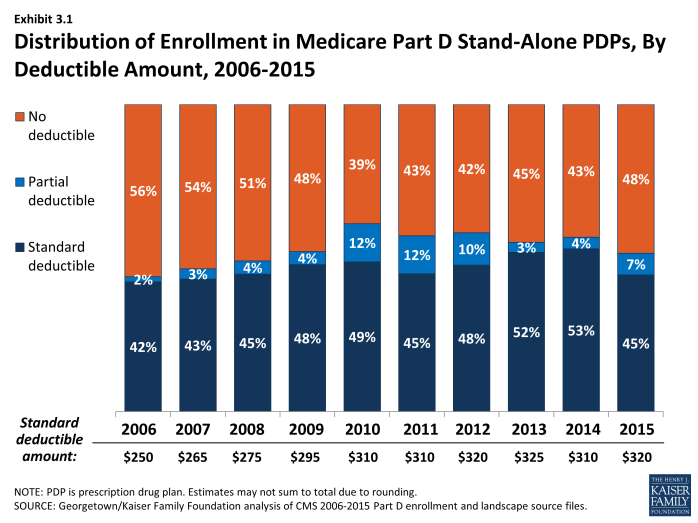

Use of a deductible by stand-alone PDPs is considerably higher in 2015 than in the first few years of the program. About 58 percent of PDPs charge a deductible this year, compared to a high of 60 percent in 2010. Most PDPs with a deductible use the standard deductible allowed by law ($320 in 2015). Nearly half of PDP enrollees are in plans with no deductible (48 percent of enrollees), compared to 56 percent of PDP enrollees in 2006 (Exhibit 3.1). A smaller number of MA-PD plans (37 percent) than PDPs have a deductible in 2015, but use of a deductible is up substantially from 2014 (14 percent). More than half of the MA-PD plans with a deductible set the level lower than the maximum of $320. Overall, 51 percent of all Part D enrollees are enrolled in plans with no deductible, and 33 percent are in plans with the maximum deductible. In contrast to Part D, only a small share of workers with employer sponsored drug coverage (12 percent) face a separate drug deductible, averaging $231 in 2015.2

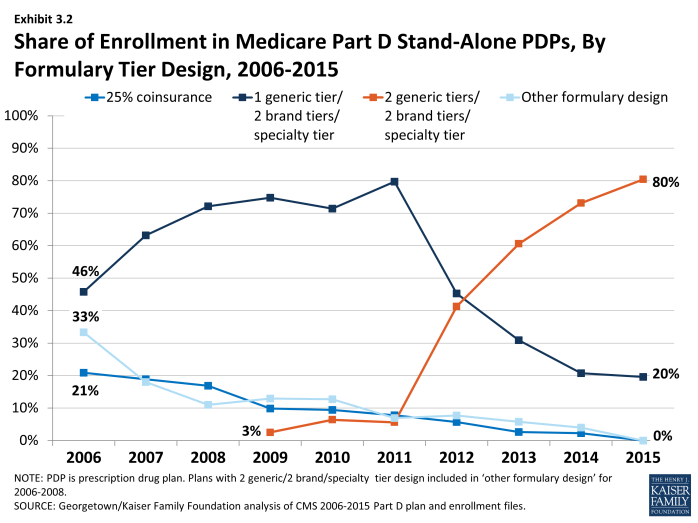

In 2015, the vast majority of all Part D enrollees (80 percent of PDP enrollees and 91 percent of MA-PD plan enrollees) are in plans that use five cost-sharing tiers: preferred and non-preferred tiers for generic drugs, preferred and non-preferred tiers for brand drugs, and a tier for high-cost specialty drugs (see section below, ‘Specialty Tiers’) (Exhibit 3.2). Overall, 84 percent of the combined enrollment in PDPs and MA-PDs are in plans with five tiers. In 2015, 90 percent of PDPs and 87 percent of MA-PD plans used five-tier designs. Most of the other Part D enrollees are in plans with four tiers: one generic tier, two brand tiers, and a specialty tier.3 By contrast, enrollees in 2006 were in PDPs with a greater variety of tier structures, including significant numbers in plans with three-tier and four-tier arrangements. Four-tier arrangements were most common until 2012 when plans began shifting toward the five-tier cost-sharing design.

Part D plans use more cost-sharing tiers than private-sector employer plans. Whereas all PDP enrollees and nearly all MA-PD enrollees are in plans with four or more tiers, only 23 percent of covered workers in employer-sponsored plans are in plans with that many tiers, while 13 percent are in plans with two tiers or no tiered cost sharing.4 The trend among employer plans has been to use more tiers, and some have gone to five tiers, but this design is used much less often than in Part D.

Part D Cost-Sharing Amounts

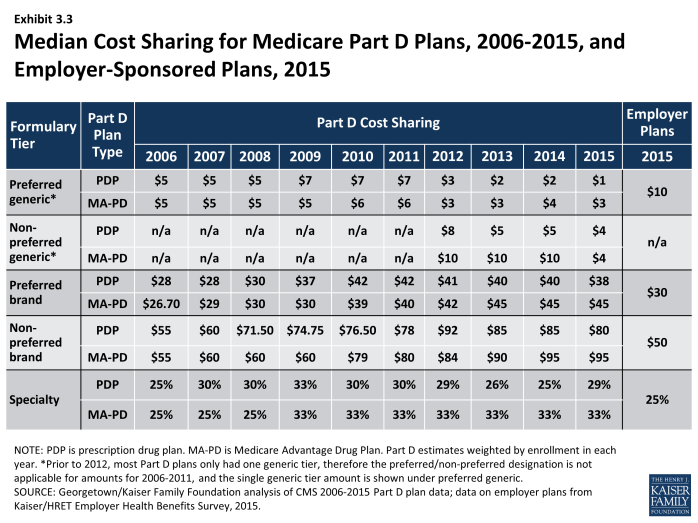

While cost sharing has been relatively stable in recent years, the median cost sharing for a 30-day supply of non-preferred brand-name drugs in stand-alone PDPs has increased by 45 percent since 2006, from $55 to $80, while cost sharing for preferred brand drugs increased by 36 percent, from $28 to $38 (Exhibit 3.3). Median cost sharing in PDPs for both brand tiers was modestly lower in 2015 compared to 2014. Cost-sharing amounts for brand-name drugs vary widely across Part D plans in 2015, as they have in previous years. For preferred brand tiers, PDPs charge copayments as low as $19 and as high as $45. About 80 percent of spending on brand drugs for Part D enrollees was for drugs on preferred brand tiers,5 so these are the cost-sharing levels encountered most often. For non-preferred brand tiers, copayments range from $35 to $95. These ranges are less than in some previous years because of CMS guidance that sets maximum allowable copayment levels.

Median cost sharing for preferred generic drugs in PDPs (or for generic drugs among plans with a single generic tier) is $1 in 2015, lower than in any year since the program began. As a result of lower generic copays, the spread between brand and generic tiers widened modestly from 2011 to 2015. For PDPs with two generic tiers (most PDPs and PDP enrollment), the median cost sharing is $1 for the preferred generic tier and $4 for the non-preferred tier. These copay amounts are lower than in any previous year; in fact, the copay for non-preferred generics is lower than the copay for the single generic tier as recently as 2011. By contrast, however, one PDP charges a $28 copayment for its non-preferred generic tier in 2015, well above any other PDP.

Despite the trend to higher cost sharing, beneficiaries’ average total out-of-pocket costs have not increased. According to MedPAC, for the average Part D enrollee not receiving the LIS, monthly out-of-pocket spending declined from $59 to $47 from 2007 to 2012 (the most recent year available).6 The impact of partially closing the coverage gap and more use of generic drugs has generally balanced the impact of higher cost sharing for brands.

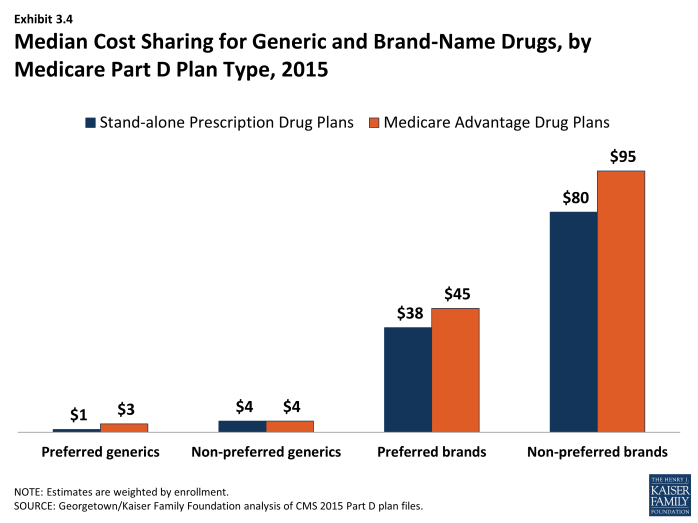

In 2015, median cost-sharing amounts are generally higher in MA-PD plans than in PDPs in all tiers. For example, the median cost sharing for preferred brands in MA-PD plans is $7 more than the median in PDPs ($45 versus $38) and $2 more for preferred generic drugs ($3 versus $1) (Exhibit 3.4). The comparisons for UnitedHealth, the sponsor with largest share of both PDP and MA-PD enrollment, illustrate the pattern. For preferred and non-preferred generic drugs, UnitedHealth’s median cost sharing, weighted by enrollment, is $2 and $5 in its PDPs and $2 and $8 in its MA-PD plans, respectively. The differences for brand drugs for UnitedHealth’s plans mirror the national differences. It is unclear why cost sharing is higher for MA-PD plans, especially since more of them offer enhanced benefits. Further work is needed to assess variations in copayments by Part D plan type, including for example, the extent to which these differences persist across all plan sponsors and within different geographic areas. Another question is whether there are differences in tier placement of specific drugs and whether some plans cover more drugs than others on specific tiers that may be factors in explaining differences in cost-sharing amounts between types of Part D plans.

Combined across PDPs and MA-PD plans in 2015, median cost-sharing amounts for generic drugs (weighted by enrollment) are $2 for preferred generics and $6 for non-preferred generics. For brand drugs, median copayments are $40 and $90 for preferred and non-preferred brands.

Copayments in the form of a flat dollar payment amount remain the most common type of cost sharing; however, the share of PDPs using percentage-based coinsurance for non-specialty brand-name drug tiers has increased since 2006. In 2015, 68 percent of PDPs with a tier for non-preferred brand drugs charge a coinsurance rate for drugs on that tier, a large jump from 37 percent in 2014. Nearly two-thirds (63 percent) of PDP enrollees are in plans with coinsurance for this tier. Of these plans, nearly all have a mixed pricing design. Typically they use a flat copayment for their generic drug tiers, and many also use a flat copayment for preferred brand drugs; 27 percent of PDPs (28 percent of enrollees) use coinsurance for preferred brand tiers, about the same as in 2014. The use of percentage coinsurance for drugs remains uncommon among MA-PD plans (13 percent for the non-preferred brand tier). In 2006, only a small share of PDPs with tiered cost sharing used coinsurance for their brand tiers (12 percent of enrollees for preferred brands and 14 percent of enrollees for non-preferred brands), but in addition nearly one-fourth of PDP enrollees were in standard plans with 25-percent coinsurance. Overall, 43 percent and 18 percent of Part D enrollees have coinsurance for non-preferred brands and preferred brands, respectively.

For plans that use percentage coinsurance instead of dollar copayments, the actual amount an enrollee pays depends on the retail price of the drug. The median coinsurance percentage for PDPs in 2015 for the preferred brand tier is 20 percent. For a brand-name drug with a typical cost of $250, the coinsurance would be $50, more than the median copay amount. For drugs on the non-preferred brand tier, the median coinsurance rate is 40 percent, a substantial share of the drug’s cost and more than the median copay for this tier. In fact, 132 PDPs (up from 29 in 2014) require beneficiaries to pay half the cost of drugs on the non-preferred brand tier, the maximum allowed under CMS guidance.

Cost sharing is generally higher in enhanced PDPs than in basic PDPs. Analysis of enhanced PDPs in earlier years sometimes revealed only small benefit differences compared to the same sponsor’s basic PDPs.7 In 2015, cost sharing in each tier is generally higher for enhanced PDPs than in basic PDPs. For generic drugs, median cost-sharing amounts (weighted by enrollment) are $3 and $5 (preferred and non-preferred tiers) for enrollees in enhanced PDPs, compared to $1 and $4 for those in basic PDPs. For brand drugs, they are $40 and $80 (preferred and non-preferred) versus $35 and $60. Enrollees in enhanced PDPs generally have no deductible, which may constitute the added actuarial value that characterizes enhanced plans. As noted in Section 2, average monthly premiums are about $20 higher for enhanced PDPs, raising questions about the value of these plans for Part D enrollees.

Medicare Part D plans generally charge more than private-sector employer plans do for preferred and non-preferred brand drugs, but less for generics. At the median, PDPs charge $38 per month for a preferred brand in 2015, higher than the median $30 charged by employer plans in 2015, (Exhibit 3.3).8 Cost-sharing differences are even greater for non-preferred brands ($80 for PDPs versus $50 for employer plans). On the other hand, only about one-fourth of workers are in employer plans that use coinsurance for brand tiers. Employer plans charge much higher copays for generic drugs than PDPs charge ($10 versus $1). Thus the spreads between cost sharing for brands and generics and between preferred and non-preferred brand drugs are greater in Medicare Part D plans. Compared to commercial health plans, the typical structure of cost sharing in Part D offers a greater incentive for plan enrollees to choose generics or preferred brand drugs. Furthermore, employer plans are much less likely to use two generic tiers.

Part D enrollees in some plans have the potential for savings if they obtain prescriptions by mail order; in other plans cost sharing is lower at retail pharmacies. Only 40 percent of PDPs (with about half of PDP enrollees) discount the cost sharing for a 90-day supply of a preferred brand drug obtained by mail order versus the same 90-day supply at retail. Among these PDPs, cost sharing is typically about 10 percent lower. About one-tenth of PDP (4 percent of enrollees) actually charge more; in most cases the cost sharing is equivalent to that charged for pharmacies not offering preferred cost sharing (see section on tiered pharmacy networks). Part D allows plans to offer mail order, but requires a level playing field in that at least one retail pharmacy must be able to dispense prescriptions with 90-day supplies. According to a recent study, mail order represented about 8 percent of prescriptions for 300 top drugs dispensed in Part D in 2010 and about 14 percent of spending on those drugs. The study found that Part D plan sponsors do not achieve savings when patients use mail order, because total mail order pharmacies may charge more for drug than retail pharmacies in Part D.9

About one-fifth of Part D PDP enrollees are in plans that offer discounted cost sharing for a 90-day supply at retail pharmacies. In 2015, 11 percent of PDPs with 19 percent of PDP enrollees have discounted cost sharing for a 90-day supply of a drug on a preferred brand tier. Most PDPs offering this discount charge the equivalent of 2.5 monthly copays for a 90-day supply, amounting to about a 17 percent discount. A handful of PDPs charge two monthly copays. All other PDPs have no discount for a 90-day supply.

Specialty Tiers

Nearly all Part D plans use a specialty tier for high-cost medications in 2015. In 2015, all PDP enrollees and 99 percent of MA-PD plan enrollees are in plans with a specialty tier. Across the two enrollee populations, 99.5 percent are in plans with a specialty tier. Specialty tiers are used by Medicare drug plans for relatively expensive drugs (at least $600 per month in 2015—a threshold that has been unchanged since 2008).

Use of specialty drugs has increased rapidly in recent years (46 percent in 2014 and 15 percent in 2013), driven by growth in the average unit cost, rather than utilization.10 The introduction of new drugs to treat hepatitis C was a large driver of the increase in 2014. Although the trend is up, specialty drugs represented only 16 percent of Part D drug spending in 2014, up from 11 percent in 2014.11 Only 2 percent of Part D enrollees used a specialty drug in 2014.

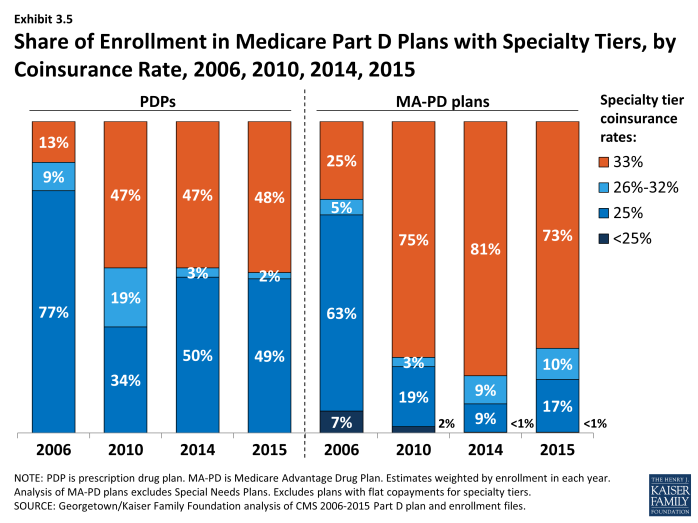

About half of PDP enrollees and most MA-PD plan enrollees are in plans with a 33 percent coinsurance rate for specialty tier drugs. While CMS limits the coinsurance rate for drugs placed on a specialty tier to 25 percent, plans are allowed to impose higher cost sharing (up to 33 percent) for specialty tier drugs if offset by a lower deductible.12 In 2015, 48 percent of PDP enrollees with a specialty tier and 73 percent of MA-PD plan enrollees in a plan with a specialty tier are in plans charging the maximum 33 percent coinsurance for specialty drugs in the initial coverage period (Exhibit 3.5). By contrast, in 2006 only 13 percent of beneficiaries in PDPs and 25 percent of enrollees in MA-PD plans with specialty tiers faced a 33 percent coinsurance rate. Overall, 57 percent of PDP and MA-PD plan enrollees are liable for 33 percent coinsurance for specialty tier drugs in 2015—up from 16 percent in 2006.

Placing a drug on the specialty tier or on a non-preferred brand tier with high coinsurance can have significant cost implications for plan enrollees, at least before they reach the catastrophic coverage phase of the Part D benefit. A specialty drug priced at the $600 threshold will cost the beneficiary between $150 and $200 per month during the initial coverage period prior to the coverage gap. But monthly cost sharing for other common specialty drugs, such as Copaxone (for multiple sclerosis), Enbrel (for rheumatoid arthritis), Gleevec (for certain cancers), and Truvada (for HIV) can range from $300 to $2,000, before a beneficiary reaches the coverage gap or qualifies for catastrophic coverage. The cost for the first month of Sovaldi, a newly approved drug for hepatitis C, can exceed $5,000.13 For beneficiaries who exceed the catastrophic coverage threshold, the cost sharing is lowered to 5 percent of the drug cost for the remainder of the year.

Tiered Pharmacy Networks

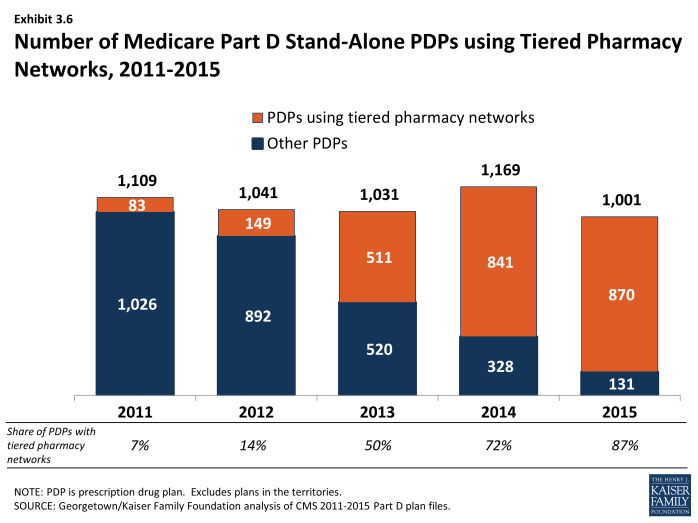

In 2015, 87 percent of all PDPs—representing 81 percent of all enrollees—have a tiered pharmacy network. By contrast, only 7 percent of PDPs (6 percent of enrollees) had a tiered pharmacy network in 2011 (Exhibit 3.6). Enrollees in these plans pay lower cost sharing for their prescriptions if they use pharmacies that offer preferred cost sharing.14 This approach to plan design started in 2011 with the market entry of co-branded PDPs featuring relationships with specific pharmacy chains, such as the Humana Walmart-Preferred Rx PDP (new in 2011) and the Aetna CVS/Pharmacy PDP (new in 2012). Many other plan sponsors designated a tiered network in 2013 or 2014, mostly without a co-branded relationship. The idea behind these arrangements is that Part D plans are able to negotiate discounted prices at certain pharmacies in exchange for higher volume of sales. The lower cost sharing creates an incentive for enrollees to use the designated pharmacies. CMS guidelines allow plans to assume use of preferred cost sharing in calculating whether cost sharing is actuarially equivalent to the defined standard benefit.

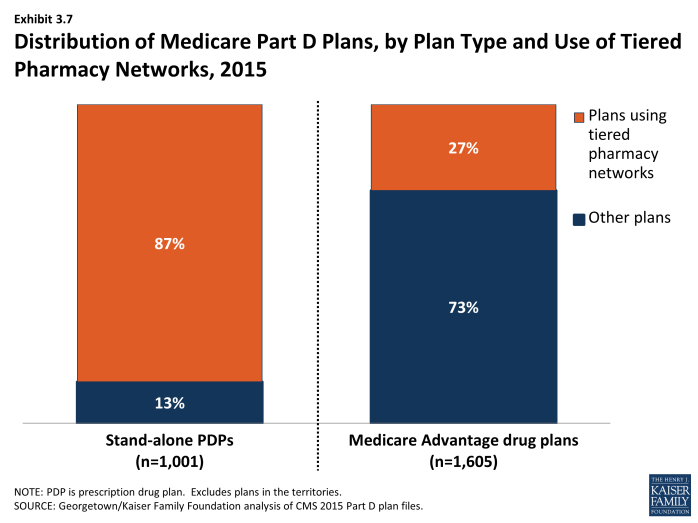

Tiered pharmacy networks have been employed much less often in Medicare Advantage. In 2015, only 27 percent of MA-PD plans (21 percent of enrollees) used tiered pharmacy networks (Exhibit 3.7). This lower rate may seem surprising given that Medicare Advantage plans generally limit networks for other types of providers. The faster adoption of this approach among PDPs compared to MA-PD plans may reflect the efforts of PDP sponsors to match practices of their competitors who were early adopters of this change.

Proportionally, the discounts in cost sharing for filling a monthly prescription in a pharmacy using preferred cost sharing is greater for generic drugs. The median discount (weighted by enrollment) is $3 for preferred generics and $5 for non-preferred generics, which represents a discount of more than half for these tiers. For brand drugs, the differential is much more modest in percentage terms but greater in dollars. The discount is $5 for the preferred tier and $10 for the non-preferred tier (5 percentage points and 13 percentage points, respectively, for plans that use coinsurance instead of copays). There are no differentials for the specialty tier.

For example, in the AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDP sponsored by UnitedHealth, the copayment for a preferred brand drug is $20 in a designated pharmacy and $45 in another network pharmacy ($35 versus $60 for other brand drugs). Copayments in the Humana Walmart Rx PDP at a designated pharmacy are $1 for drugs on the preferred generic tier and $4 for drugs on the non-preferred generic tier, compared to $10 and $33, respectively, at other network pharmacies. Coinsurance differences for this Humana PDP are 20 percent versus 25 percent for a preferred brand drug and 35 percent versus 50 percent for a non-preferred brand drug.

Although the difference in cost for filling a single prescription is modest, the financial consequences for non-LIS Part D plan enrollees if they do not use pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing can add up for beneficiaries taking multiple brand-name drugs.15 An enrollee in the AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDP who fills two brand drugs and one generic drug per month might pay an extra $624 over the year if she does not use one of the designated pharmacies; an enrollee in Humana Walmart Rx PDP might pay an extra $228.

In 2014 (the most recent available data), PDPs with tiered pharmacy networks designated only about 24 percent of their network pharmacies as offering preferred cost sharing.16 But the size of the preferred cost sharing networks varied enormously from 1 percent to 99 percent of plans’ overall networks. Overall, access to pharmacies is high. Most PDPs contract with at least 95 percent of all available pharmacies in their full pharmacy network.17 But generally plan sponsors do not offer the preferred terms to all pharmacies in their networks.

Limited information is available on the share of plan enrollees who fill prescriptions at pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing. A CMS analysis of 2012 claims data found that the share of retail claims in pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing ranged from 19 percent to 79 percent across 13 plans. For 7 of the 13 plans, the share of claims in pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing was 37 percent or less.18

For some PDPs, access to pharmacies with preferred cost sharing is limited. For some plans, there are few or no designated pharmacies within a reasonable travel distance.19 Medicare law requires that retail pharmacy networks as an entirety meet standards whereby certain shares of beneficiaries must have access to a network pharmacy close to their residence, with separate tests for urban, suburban, and rural areas.20 For example, 90 percent of beneficiaries in urban areas must have a network pharmacy within two miles of their home (90 percent within 5 miles for suburban areas and 70 percent within 15 miles in rural areas). CMS ensures that all plans meet these standards for their full pharmacy networks. But CMS found that 46 percent of PDPs or MA-PD plans would have failed if the test was applied just to the pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing.21 Plans were more likely to fail in urban area, whereas most plans would have met the standard in suburban and rural areas. If the urban access standard were widened from two miles to 4.5 miles, 90 percent of plans would have met the standard.

Plans sponsored by Humana illustrate the trend. In 2014, Humana’s PDPs on average designated only 10 percent of their network pharmacies as preferred, a lower rate than other national plan sponsors.22 Because Humana’s PDPs rely solely on Walmart pharmacies, access is lacking in urban areas where Walmart has no market presence.

In the call letter issued in April 2015, CMS indicated that it will monitor pharmacy networks and encourage plans to take action if they have too little meaningful access to the pharmacies that offer preferred cost sharing.23 Effective in 2016, the Medicare program intends to improve transparency by publishing information on plans’ access levels for the designated pharmacies. The agency will also require a sponsor to disclose in marketing materials if its network is an outlier on access standards. But the agency has not established specific access standards for tiered pharmacy networks offering preferred cost sharing, beyond the statutory standards that already apply to the overall networks.

Formularies and Utilization Management

In 2015, the average PDP enrollee is in a plan where the formulary lists 83 percent of all eligible drugs, the same as in 2013 and 2014 but slightly below the average in prior years. The scope of formulary coverage, however, continues to vary widely across PDPs in 2015. Some plans list all drugs from the CMS drug reference file on their formularies, while other PDPs list as few as 66 percent of these drugs.24 Even the most limited formularies, however, exceed the formulary requirements established under law and CMS program guidance.25 The seven largest PDPs range in formulary coverage from 74 percent to 89 percent of drugs in the reference file.26 The average MA-PD plan enrollee is in a plan with slightly more drugs on formulary (87 percent) than PDPs. Beneficiaries retain the option of requesting an exception to have the plan cover an off-formulary drug, or they can obtain the drug by paying the full purchase price out of pocket.

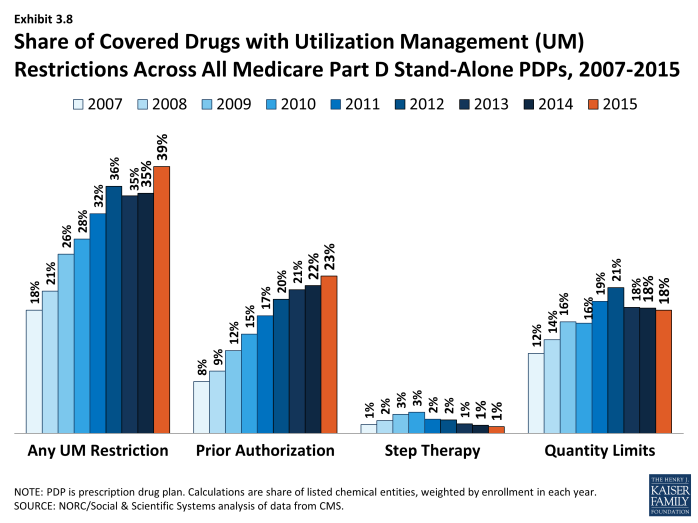

Since 2007, PDPs have applied utilization management (UM) restrictions to an increasing share of on-formulary drugs, increasing from 18 percent in 2007 to 39 percent in 2015 (Exhibit 3.8). Even if a drug is listed on a plan’s formulary, utilization management rules, including step therapy, prior authorization, and quality limits, may restrict a beneficiary’s access to the drug.27 In 2015, more drugs are subject to prior authorization than to other UM tools. On average across all PDPs (weighted for enrollment), prior authorization is applied to 23 percent of formulary drugs, about three times the use in 2007. Quantity limits (e.g., limiting a prescription to 30 pills for 30 days) are applied to 18 percent of drugs in 2015, whereas only 1 percent of drugs are subject to step therapy. MA-PD plans tend to apply UM restrictions to about the same share of drugs as PDPs.

The Coverage Gap

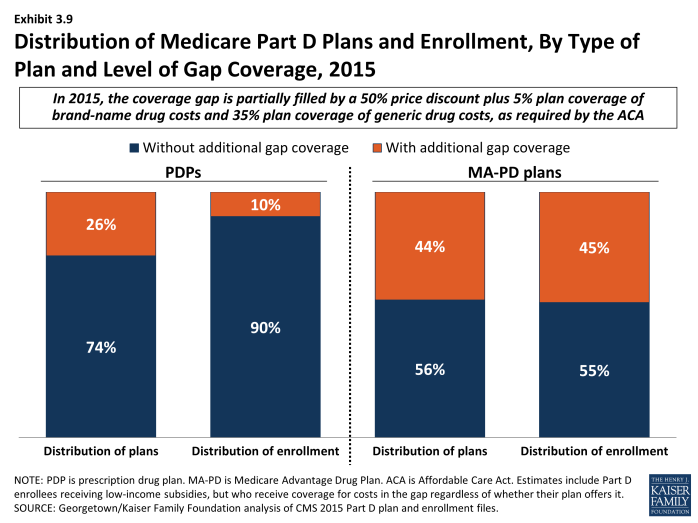

In 2015, most PDPs (74 percent) offer no gap coverage beyond what is required by law; PDPs offering extra gap coverage cost more and have attracted fewer enrollees (Exhibit 3.9). In 2015, beneficiaries reaching the gap pay 45 percent of the full price for brand-name drugs in the gap (after a manufacturer price discount of 50 percent; plans pay the remaining 5 percent), and 65 percent of the cost for generics (plans pay the remaining 35 percent). Under current law, beneficiaries will face average cost sharing of only 25 percent for all drugs in the gap by 2020—the same as in the initial coverage period—effectively eliminating the coverage gap.

Plans offering gap coverage typically cover only a subset of drugs when enrollees are in the coverage gap. In past years, CMS has differentiated gap coverage by shares of drugs covered in the gap (few, some, many, or all). The agency terminated these descriptions starting in 2015 on the basis that they are no longer relevant as a result of phasing out of the coverage gap. In our analysis for past years, we classified plans labeled by CMS as covering few brands or few generics (defined as less than 10 percent of drugs in a particular category) as having “little or no coverage.” Because those distinctions are no longer available, some plans labeled as having gap coverage may have additional coverage for only a minimal share of drugs.

In 2015, 90 percent of all PDP enrollees are in plans without additional gap coverage beyond what is required by law (Exhibit 3.9). Overall, however, only 49 percent of PDP enrollees are potentially exposed to the gap in coverage if their spending exceeds the initial coverage limit. This lower percentage reflects the fact that LIS enrollees pay the same modest cost-sharing amounts in the gap as in the initial coverage period. In 2015, the vast majority of non-LIS Part D enrollees (84 percent) are enrolled in PDPs with no gap coverage beyond what is required by the ACA.

A larger share of MA-PD plans (44 percent) than PDPs (26 percent) offer additional gap coverage in 2015, and a much larger share of MA-PD plan enrollees than PDP enrollees are in such plans. Nearly half (45 percent) of MA-PD plan enrollees have at least some additional gap coverage beyond what the ACA requires, well above the 10 percent for PDP enrollees (Exhibit 3.9). The higher level of additional gap coverage among enrollees in MA-PD plans occurs largely because Medicare Advantage plans are able to use payments received from the government for providing benefits covered under Parts A and B to reduce cost sharing and premiums under Part D.28 Furthermore, because Medicare Advantage plans cover hospital and physician services and other Medicare benefits, they have stronger incentives than PDPs to offer at least some gap coverage to forestall the negative health and cost consequences that could arise if enrollees do not take their medications when they reach the gap. Despite these incentives, a majority of MA-PD plans offer no additional gap coverage. Overall, 77 percent of enrollees in PDPs or MA-PD plans are in plans with no gap coverage.

In earlier years, most Part D enrollees with gap coverage (beyond that required by law) were in plans that covered only some generic drugs in the gap. For example, in 2014, only about 3 percent of PDP enrollees and less than 1 percent of MA-PD plan enrollees had any significant gap coverage for brand-name drugs beyond the coverage that all plans must provide. Furthermore, most plans with gap coverage for generics included only a share of all generic drugs in that coverage. Although CMS no longer provides this breakdown, it is likely that the generosity of gap coverage beyond with the ACA requires plans to offer remains limited.

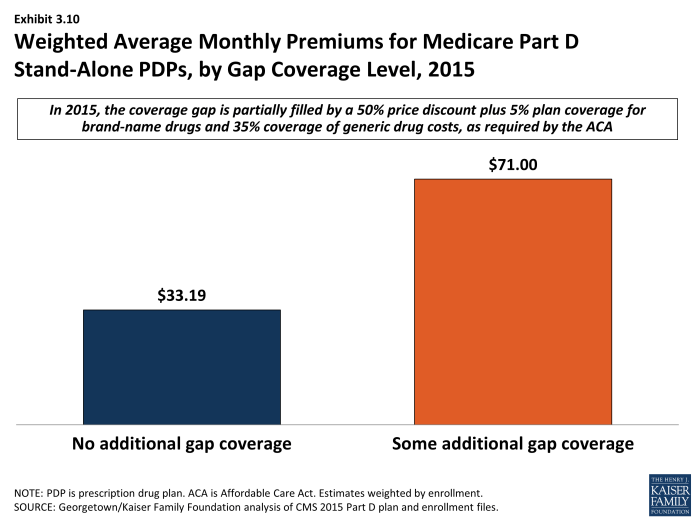

Enrollees in stand-alone Part D plans tend to pay substantially higher premiums for plans with gap coverage (beyond that which is required by law) compared to those without such coverage. On average, the weighted monthly premium for a stand-alone PDP offering additional gap coverage for at least some drugs is $71.00, about $38 per month above that for plans offering no gap coverage, despite the limited added coverage provided by these plans (Exhibit 3.10).