Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services Programs: 2012 Data Update

Eligibility and Cost Containment Policies Used in Medicaid HCBS Programs in 2014

Medicaid § 1915(c) Waivers

The Medicaid § 1915(c) waiver authority allows states to use a range of cost-containment strategies to meet federal cost neutrality requirements and limit spending so that expenditures do not exceed state budgetary restrictions. To understand how states controlled spending on HCBS waivers in 2014, we surveyed all state § 1915(c) waiver program administrators to assess financial and functional eligibility standards, use of enrollment and/or expenditure caps, and waiting list status (i.e., number of individuals on the list(s) and average waiting time). The survey finds that every state used some type of cost-containment tool in its § 1915(c) waivers beyond the federal cost neutrality requirement that average annual per participant waiver spending not exceed average per participant spending if services were provided in an institutional setting under the state plan absent the waiver. The following summary of the 2014 survey findings illustrates how states use cost control policies to limit access to § 1915(c) waivers.

Financial Eligibility

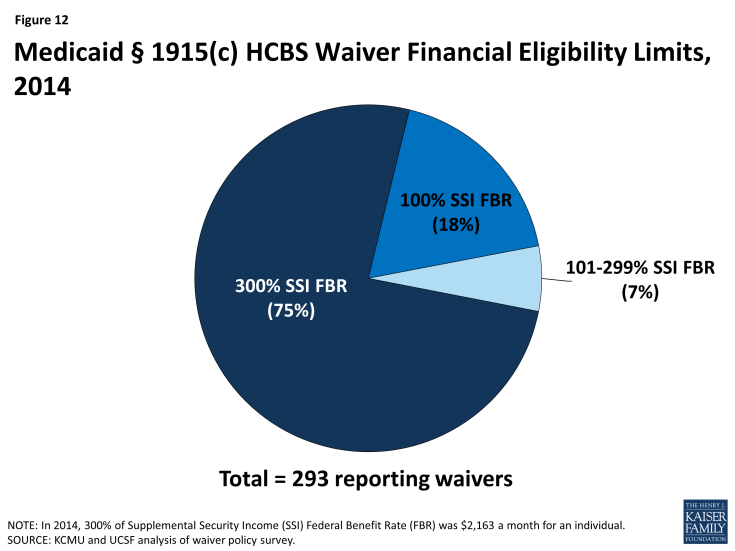

Most states set their Medicaid financial eligibility standard for nursing facility services at 300 percent of the federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) federal benefit rate ($2,163/month for an individual in 2014). States may set financial eligibility standards for Medicaid § 1915(c) waivers at the same level as that for nursing facilities. There is, however, wide variation in financial eligibility standards across states and HCBS waiver programs as shown in Table 11. Twenty-five percent of reporting waiver programs used more restrictive financial eligibility standards (e.g., 100% of SSI) than used for nursing facilities (300% of SSI) in 2014 (Table 11 and Figure 12).

Functional Eligibility

Another way states limit eligibility for § 1915(c) waivers is by using functional eligibility criteria that are stricter than those used for coverage of nursing facility care. For example, a state could require an individual to exhibit difficulty in performing at least three activities of daily living” (ADLs), (e.g., bathing, dressing, transferring, eating, toileting) for waiver eligibility but require limitations in only two ADLs for nursing facility admission. The 2014 survey found that 10 § 1915(c) waiver programs (3%) used functional eligibility criteria that are more restrictive than the criteria used for institutional care (no table shown); these waivers were reported in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, New York, Texas, and Utah.

Cost Controls

Approximately 88 percent (42 states) of all states with § 1915(c) waivers utilized some form of cost controls above and beyond the federally mandated cost neutrality formula in 2014. Many states used a mixture of fixed expenditure caps, service provision and hourly caps, and geographic limits (Table 12). Of the states with waiver cost controls in place, half (21 states) utilized more than one form, such as a combination of expenditure caps and service limitations (Table 12).

Self-Direction

Many states have incorporated some form of mandatory or optional self-direction within their § 1915(c) waivers. The self-direction service delivery model can include initiatives such as beneficiary choice in the allocation of service budgets and/or the selection, training, and dismissal of service providers. In 2014, 179 waivers in 42 states (61% of waivers and 90% of states) either allowed or required some form of self-direction (Table 12).

Waiting Lists

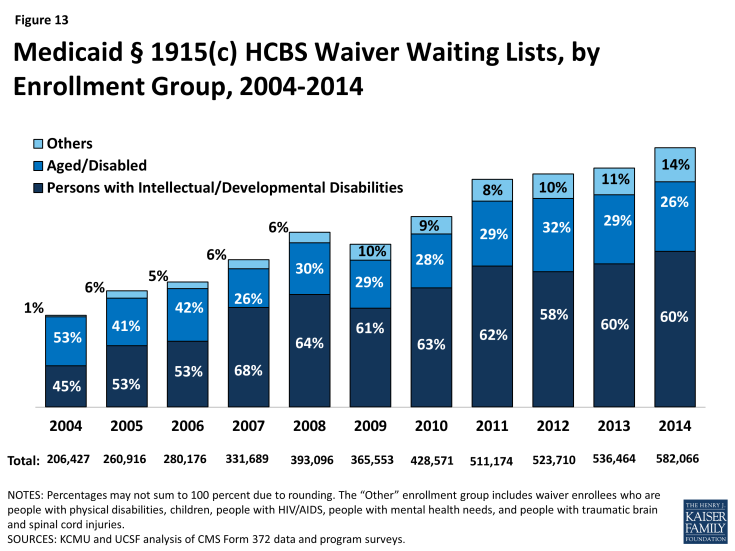

States often have more individuals who need Medicaid home and community-based waiver services than the number of available spaces, called “slots,” in a § 1915(c) waiver (Table 13). Many states maintain waiting lists when their program slots are filled or when state legislatures do not fully fund the maximum number of slots approved by CMS. In 2014, 39 states reported waiver waiting lists while 8 states and DC reported no such lists (Table 14). In 2014, there were 582,066 individuals on waiver waiting lists across 154 § 1915(c) waivers. Section 1915(c) waivers for people with I/DD had the greatest number of individuals on waiting lists (349,511 individuals, or 60% of total waiting list enrollment) followed by waivers serving people who are aged and aged or disabled (155,697 individuals, or 27% of total waiting list enrollment) (Table 14, Figure 13). Most states reported that virtually all of the persons on waiver waiting lists currently reside in the community and not in an institution, although they may still be at risk of institutionalization. Due to the varying number of waiver slots available for each population, the average length of time an individual spent on a waiting list varied by population and ranged from three months for HIV/AIDS waivers to 47 months for I/DD waivers, with an average national waiting time of 29 months across all § 1915(c) waivers with waiting lists (Table 14).

The number of individuals on § 1915(c) waiver waiting lists grew by 8.5 percent from 2013 to 2014, far outpacing the growth rate of 2 percent in the 2012-2013 period. From 2004 to 2014, waiting list enrollment grew by an average of 11 percent annually. Waiting lists for all § 1915(c) waiver target populations increased, with the exception of waivers for people who are aged as well as those for persons with HIV/AIDS (Table 14). The maintenance and length of state waiver waiting lists has implications for states’ compliance with the Olmstead decision which requires states to provide services outside of institutions if beneficiaries are able to live in the community and do not oppose doing so.

In 2014, more than two-thirds (68%) of all § 1915(c) waivers with waiting lists had a policy of screening individuals for Medicaid waiver eligibility before being placed or while on a waiting list (Table 13). In addition, almost three quarters (73%) of all waivers with waiting lists had a policy of prioritizing certain individuals for waiver services (e.g., persons transitioning to the community from an institution) get priority for waiver services when slots become available). Ninety-two percent of all waivers with waiting lists provided non-waiver services (i.e., state plan services) to Medicaid eligible individuals while they awaited a waiver slot.