Medicaid Enrollment & Spending Growth: FY 2020 & 2021

Key Takeaways

The coronavirus pandemic has generated both a public health crisis and an economic crisis, with major implications for Medicaid, a countercyclical program. During economic downturns, more people enroll in Medicaid, increasing program spending at the same time state tax revenues may be falling. To help both support Medicaid and provide broad fiscal relief as revenues have declined precipitously, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) authorized a 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal match rate (“FMAP”) (retroactive to January 1, 2020) available if states meet certain “maintenance of eligibility” (MOE) requirements. The health and economic consequences of the pandemic as well as the temporary FMAP increase were major drivers of Medicaid enrollment and spending trends as states finished state fiscal year (FY) 2020 and started FY 2021 (which for most states began on July 1).1

This brief analyzes Medicaid enrollment and spending trends for FY 2020 and FY 2021 based on data provided by state Medicaid directors as part of the 20th annual survey of Medicaid directors in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Overall, 43 states2 responded to the survey by mid-August 2020, although response rates for specific questions varied. The methodology used to calculate enrollment and spending growth as well as additional information about Medicaid financing can be found at the end of the brief. Key findings include the following:

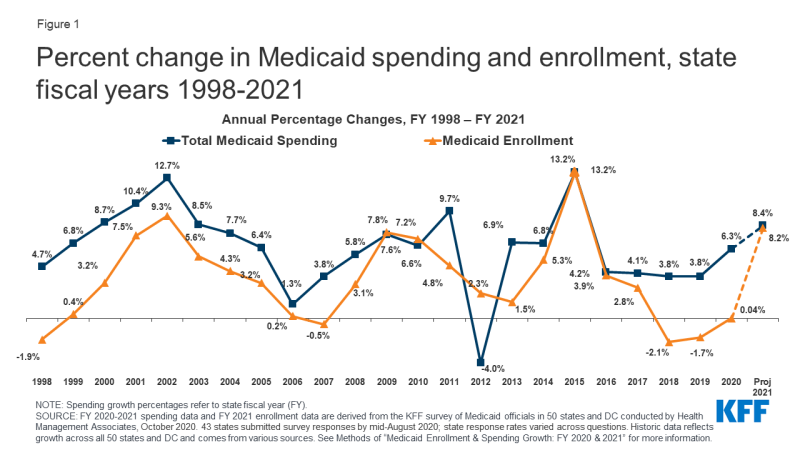

- After relatively flat enrollment growth in FY 2020 (0.04%), states responding to the survey expect Medicaid enrollment to jump in FY 2021 (8.2%) attributed to the FFCRA’s MOE requirements and to the economic downturn that started late in FY 2020.

- Across all reporting states, states were anticipating that total Medicaid spending growth would accelerate to 8.4% in FY 2021 compared to growth of 6.3% in FY 2020. Enrollment was the primary factor identified as putting upward pressure on expenditure growth in FY 2021.

- While expected state spending on Medicaid is crucial to state budgets, the projections in this year’s survey do not provide a clear picture because enhanced federal funding is now slated to expire at the end of March 2021 based on the recent renewal of the Public Health Emergency (PHE), later than states had generally assumed. At the time of the survey, states estimated that state Medicaid spending would decline in FY 2020 (-0.5%) and then sharply increase in FY 2021 (12.2%) with most states assuming that the enhanced matching funds would expire by December 2020.

- Looking ahead, states are faced with many layers of uncertainty about the trajectory of the pandemic and economic downturn as well as the duration of the enhanced FMAP and the outcome of the elections in November.

Context

Medicaid (together with CHIP) provided coverage to about one in five Americans, or about 73.5 million people, as of May 2020. Total Medicaid spending was nearly $604 billion in FY 2019 with 64.4% paid by the federal government and 35.6% financed by states. Medicaid accounts for one in six dollars spent in the health care system and more than half of spending on long-term services and supports.3

Prior to the pandemic, state fiscal conditions were strong in FY 2020. Unemployment was low, states expected revenues to grow for the 10th consecutive year, and state general fund spending was on track to grow by 5.8%. In this context, Governors had developed budget proposals for FY 2021 that included projections for continued revenue and spending growth. Governors’ budgets are generally released early in the calendar year.

The pandemic resulted in a dramatic reversal in state fiscal conditions. Early estimates indicate that states are facing large shortfalls, with some estimates showing state budget shortfalls of up to $110 billion for FY 2020 and up to $290 billion for FY 2021. Other early reports from states similarly show state revenue declines of up to 15% in FY 2020 and up to 30% for FY 2021 compared to pre-pandemic state estimates of state revenue totaling $913 billion for FY 2020 and $944 billion in FY 2021. Faced with continued uncertainty regarding ongoing revenue collections and the possibility of additional federal fiscal relief, several states adopted temporary budgets or continuing resolutions to begin FY 2021 while some other states with previously enacted FY 2021 budgets planned to convene special sessions to adjust appropriation levels.4 Unlike the federal government, states must meet balanced budget requirements. In the face of major revenue shortfalls due to the economic effects of the pandemic, states can use reserves or cut spending if additional federal support is not available. During the Great Recession, states imposed layoffs or furloughs for state workers, reduced funding for state governments, made across the board spending cuts and program cuts to education, higher education, and Medicaid. However, major cuts to state services and workforce can be harmful to state residents facing increased demands for services and can also weaken economic recovery efforts. To reduce Medicaid spending during economic downturns, states typically turn to provider rate and benefit restrictions, however, with providers facing revenue shortfalls and enrollees facing increased health risks due to the pandemic, these methods to control costs may not be as viable.

While the FMAP increase included in the FFCRA supports Medicaid and provides broad fiscal relief to states, it is unlikely to fully offset state revenue declines and fully address state budget shortfalls. In the past, federal fiscal relief provided through increases in the Medicaid FMAP—or the share of Medicaid costs paid by the federal government— during significant economic downturns has helped to both support Medicaid and provide efficient, effective, and timely fiscal relief to states. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) uses this model as well by providing a temporary 6.2 percentage point increase in the Medicaid FMAP from January 1, 2020 through the end of the quarter in which the public health emergency (PHE) ends. This FMAP increase does not apply to the ACA expansion group, for which the federal government already pays 90% of costs. To be eligible for the funds, states cannot implement more restrictive Medicaid eligibility standards or higher premiums than those in place as of January 1, 2020, must provide continuous eligibility for enrollees through the end of the month of the emergency period, and cannot impose cost sharing for COVID-19 related testing and treatment services including vaccines, specialized equipment, or therapies. States access the enhanced funds by submitting claims for federal reimbursement for Medicaid expenditures.

While all states are experiencing fiscal stress tied to the pandemic, the experience varies across states. For example, while the national unemployment rate in August 2020 was 8.4% (a decline from its initial peak of 14.7% in April 2020 at the start of the pandemic), there was considerable state variation in unemployment with state rates ranging from 4.0% (Nebraska) to 13.2% (Nevada). California, Hawaii, New York, Rhode Island and Nevada reported the highest state unemployment rates, exceeding the national rate by three percentage points or more. Similarly, projected revenue shortfalls vary across states, with states reporting revenue declines ranging from 1% to 15% in FY 2020 and from 1% to 30% for FY 2021.

Key Findings

Trends in Enrollment Growth FY 2020 and FY 2021

After declines in FY 2018 and 2019 followed by relatively flat enrollment growth in FY 2020, states expect Medicaid enrollment to jump in FY 2021 (Figure 1). Medicaid enrollment growth peaked in FY 2015 due to the implementation of the ACA and has tapered each year since. Enrollment declined in FY 2018 (-2.1%) and FY 2019 (-1.7%) and was relatively flat in FY 2020 (0.04%). However, for FY 2021, reporting states project a sharp increase in enrollment to 8.2%. A few states noted that the projections were completed prior to the pandemic and did not account for the economic downturn so were likely to change. Others noted uncertainty regarding when the PHE and related maintenance of effort (MOE) requirements would end, which would allow redeterminations and eligibility terminations to resume for beneficiaries who no longer meet eligibility standards (although fewer enrollees are likely to see income increase due to the economic downturn). A few states that recently adopted or implemented the Medicaid expansion anticipated larger increases in enrollment.

States largely attributed projected enrollment increases in FY 2021 to the FFCRA’s MOE requirements and to the economic downturn. All reporting states responded that the MOE was an upward or significant upward pressure on enrollment and nearly all reporting states noted that the economy was an upward or significant upward pressure on enrollment. The two factors (the MOE and the economy) are likely linked. Outside of the MOE, individuals may lose Medicaid coverage because they have a change in circumstance (such as an increase in income), because they fail to complete renewal processes or paperwork even when they remain eligible, or because they age out of a time- or age-limited eligibility category (e.g., pregnant women or former foster care youth). Due to the economic downturn, fewer enrollees are likely to see income increase, meaning they would remain eligible for Medicaid irrespective of the MOE. States anticipate that groups more sensitive to changes in economic conditions (e.g., children, parents, and other expansion adults) will grow faster than the elderly and people with disabilities; however, an aging state population was also identified as a key factor driving enrollment in almost half for reporting states. In last year’s survey, states tied declines in enrollment growth prior to the pandemic to a more robust economy, but also to process and systems changes including changes to renewal processes, upgraded eligibility systems, and enhanced data matching efforts to verify eligibility.

Trends in Spending Growth FY 2020 and FY 2021

Among reporting states, growth in total Medicaid spending was 6.3% in FY 2020, but is expected to jump to 8.4% in FY 2021 (Figure 1). High rates of enrollment growth, tied first to the Great Recession and later to the implementation of the ACA, were the primary drivers of total Medicaid spending growth over the last decade. Similarly, declining enrollment driven by a strong economy was the primary driver identified by states for slow total Medicaid spending growth in FY 2019. Even though enrollment growth was nearly flat in FY 2020, spending was in line with median spending growth over the last two decades. In last year’s survey, Medicaid officials indicated growth in total Medicaid expenditures for FY 2020 was largely tied to increasing costs for prescription drugs (particularly for specialty drugs), rate increases (most often for managed care organizations, hospitals, and nursing facilities), overall medical inflation, pressures from an aging state population, and a higher acuity case-mix.

For FY 2021, nearly all states expect enrollment increases to put upward pressure on total Medicaid expenditure growth, with additional upward pressure coming from spending on long-term services and supports and provider rate changes. Further, about three-quarters of states noted that utilization was a factor for Medicaid spending: slightly more than half of these states identified utilization as an upward pressure on projected spending while the remaining states indicated utilization was expected to be a downward pressure (likely due to pandemic-related utilization reductions). Overall, while many reporting states were uncertain or thought that the chance of a Medicaid budget shortfall was “50-50,” more states anticipated that a budget shortfall was “likely” or “almost certain” compared to “unlikely”; so, it is possible that current expenditure growth projections could be lower than what states actually experience.

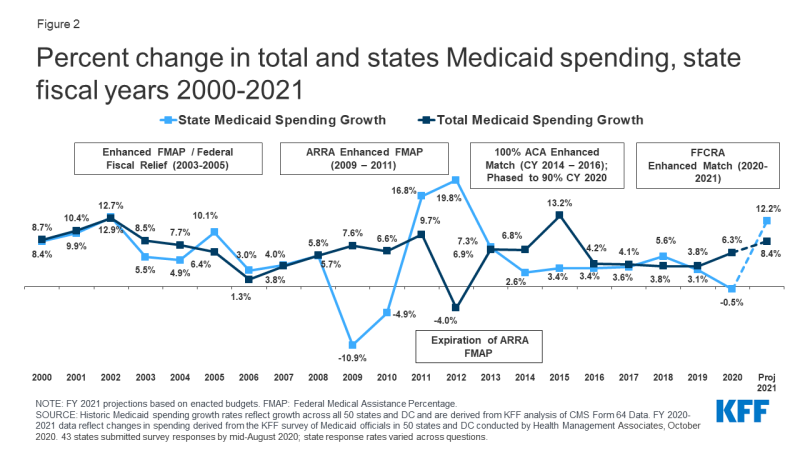

Estimates that state Medicaid spending would decline in FY 2020 (-0.5%) and then sharply increase in FY 2021 (12.2%) were made prior to the most recent renewal of the PHE that extends the enhanced FMAP through March 2021 (Figure 2). The enhanced FMAP under FFCRA was retroactive to January 1, 2020 (halfway through most state fiscal years). The fiscal relief expires at the end of the quarter in which the Public Health Emergency (PHE) ends. On October 2, 2020 the PHE was extended from October 23, 2020 to January 21, 2021, leaving the enhanced FMAP in place through March 2021. However, states adopted budgets for FY 2021 prior to the most recent extension of the PHE, with most states anticipating that the enhanced FMAP would end by December 2020 or before. The anticipated expiration of the enhanced FMAP in 2020 along with overall increases in base Medicaid spending expected in FY 2021 resulted in a spike in projected state spending.

Nearly all reporting states indicated that federal fiscal relief is being used to support costs related to increased Medicaid enrollment and to help address Medicaid or general budget shortfalls. About two-thirds of reporting states said the fiscal relief is also being used to mitigate provider rate and/or benefit cuts. The state share of Medicaid spending typically grows at a similar rate as total Medicaid spending growth, unless there is a change in the federal matching rate. During the Great Recession, state spending for Medicaid declined in FY 2009 and FY 2010 due to fiscal relief from a temporary increase in the federal match rate provided in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). State spending increased sharply when that fiscal relief ended. In other economic downturns (including the Great Recession), states typically turn to provider rate and benefit restrictions to reduce Medicaid spending, however, with providers facing revenue shortfalls and enrollees facing increased health risks due to the pandemic, these methods to control costs may not be as viable.

Conclusion and Looking Ahead

States are faced with many layers of uncertainty about the trajectory of the pandemic and economic downturn. Several states had adopted temporary budgets or continuing resolutions to start FY 2021, while other states noted FY 2021 state budgets had not yet been enacted. Some states planned to convene special sessions to make budget adjustments and noted further FY 2021 budget reductions were planned or likely. Unlike the federal government, states must meet balanced budget requirements. In the face of major revenue shortfalls due to the economic effects of the pandemic, states can use reserves or cut spending if additional federal support is not available. To reduce spending during economic downturns, states typically turn to provider rate and benefit restrictions, however, with providers facing revenue shortfalls and enrollees facing increasing health risks due to the pandemic, these methods to control costs may not be as viable. For now, states cannot restrict enrollment and must provide continuous coverage for current enrollees to access the enhanced Medicaid match rate in the FFCRA.

Looking ahead, states are also unsure about the duration of the PHE and the enhanced FMAP, whether Congress will consider additional fiscal relief, and the outcome of the elections. It is unclear if the PHE will be extended beyond the January 21, 2021. States have called for and the House passed legislation to increase the amount and duration of this federal fiscal relief, but to date the Senate has not considered these provisions. In addition, the US presidential election in November could have major implications for Medicaid, with a sharp contrast in goals for Medicaid and the ACA between President Trump and former Vice President Biden. Beyond the presidential election, the outcome of state elections (both governors and the make-up of state legislatures) will be important to watch.