Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2017: Findings from a 50-State Survey

Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility

Most income eligibility limits for Medicaid and CHIP are based percentages of the federal poverty level (FPL). As of 2016, the FPL was $20,160 for a family of three and $11,880 for an individual. The ACA established a minimum Medicaid eligibility level of 133% FPL for children, pregnant women, and adults as of January 2014, and included a standard income disregard of five percentage points of the federal poverty level, which effectively raises this limit to 138% FPL. This expansion made many parents and other adults newly eligible for the program. Before the ACA, most states limited eligibility levels for parents to less than the poverty level and other adults generally were not eligible regardless of income. As enacted, the Medicaid expansion was to be implemented nationwide. However, the 2012 Supreme Court ruling on the ACA made the expansion to low-income adults optional. The minimum continues to apply nationwide for children and pregnant women, and, as a result of the minimum, 18 states transitioned coverage for some older children from separate CHIP programs to Medicaid during 2014.

The ACA also changed how financial eligibility is determined for non-disabled groups in Medicaid, including children, pregnant women, parents, and the new expansion adults, to be based on Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI), as defined in the Internal Revenue Code. The ACA eliminated the use of income disregards and deductions other than the new standard disregard of five percentage points of the FPL and required states to convert their pre-ACA eligibility levels to MAGI-equivalent levels.

The findings below show eligibility levels for children, pregnant women, parents and other adults as of January 2017, and identify changes in eligibility that states made between January 2016 and 2017.

Children

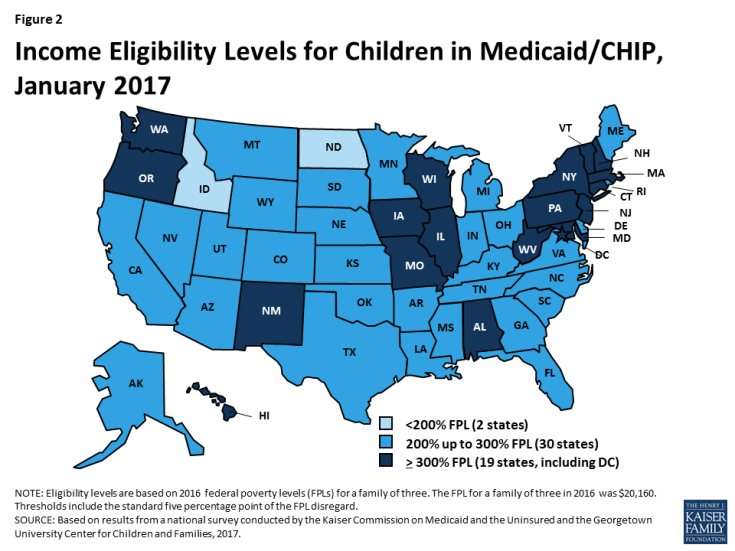

As of January 2017, 49 states cover children with incomes up to at least 200% FPL through Medicaid and CHIP, including 19 states that cover children with incomes at or above 300% FPL (Figure 2). Only two states (Idaho and North Dakota) limit children’s Medicaid and CHIP eligibility to lower incomes. Across states, the upper Medicaid/CHIP eligibility limit for children ranges from 175% FPL in North Dakota to 405% FPL in New York. Consistent with the past several years, children’s Medicaid and CHIP eligibility remained largely stable during 2016, with the exception of Michigan expanding eligibility to children with incomes up to 400% FPL who were affected by the Flint water crisis.1 This stability reflects the ACA’s maintenance of effort provision, under which states must keep children’s eligibility levels at least as high as the levels they had in place when the law was enacted in 2010 until 2019.

CHIP plays a substantial role covering children across states. As of January 2017, 36 states operate separate CHIP programs, and CHIP funding covers some children in Medicaid in 49 states. As of January 2017, enrollment is open in all separate CHIP programs. Arizona reopened enrollment in its CHIP program in July 2016; it had been closed to enrollment since late 2009, just prior to enactment of the ACA.

Several states took up options to cover more children through Medicaid and CHIP in 2016.

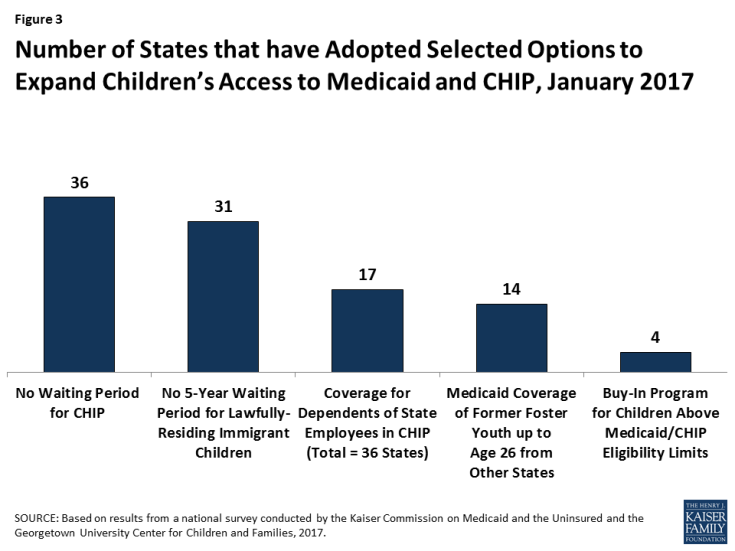

- Eliminating waiting periods for CHIP coverage. States can require children to be uninsured for up to 90 days before enrolling in CHIP. States have used these waiting periods as an approach to discourage families from dropping private insurance to enroll in the program. However, the number of states requiring a waiting period has declined over time, particularly after the ACA, since one of the ACA’s goals is to eliminate gaps in coverage. This decline continued in 2016, with Georgia and New York eliminating their waiting periods for CHIP. With these changes, as of January 2017, 36 states have no waiting period for CHIP coverage (Figure 3).

- Extending coverage to lawfully residing immigrant children. Longstanding rules require that lawfully present immigrants who are otherwise eligible for Medicaid or CHIP must wait five years from the time they receive a qualified immigration status before they may enroll. However, states have the option to eliminate this five-year waiting period for lawfully present immigrant children and pregnant women. In 2016, Florida and Utah took up this option for children. With these additions, as of January 2017, 31 states cover lawfully present immigrant children in Medicaid and/or CHIP without a five-year waiting period. In addition, six states (California, District of Columbia, Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, and Washington) use state-only funds to cover income-eligible children who are not otherwise eligible due to immigration status. This count includes the statewide expansion of coverage for all income-eligible children in California in May 2016.

- Allowing dependents of state employees to enroll in CHIP. In January 2016, Tennessee became the 17th state to adopt an option available to cover certain dependents of state employees in CHIP. Under this option, states can give part-time workers and other state employees who lack access to affordable dependent coverage in the state employee health plan the option to enroll their children in CHIP.

- Expanding coverage for former foster youth. Under the ACA, youth who were formerly in foster care in the state are eligible for Medicaid until age 26. This provision mirrors the ACA change that allowed young adults to remain on their parents’ health plan until age 26. However, extending Medicaid coverage to former foster youth from other states was a state option. With the addition of Utah during 2016, 14 states had taken up this option. In November 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released regulations, which clarified that states could not cover former foster youth from other states through a state option but could do so under Section 1115 waiver authority. CMS indicated in guidance that it will work with the 14 states that have adopted this coverage to transition it to waiver authority. 2

Four states have maintained programs that allow families above the upper income eligibility limit to buy into Medicaid or CHIP coverage for their children as of January 2017.3 The number of states offering buy-in programs declined from a peak of 15 in 2011 to 4 as of January 2017. An increasing number of states eliminated these programs in recent years, because many families above Medicaid and CHIP income limits gained new coverage options through the Marketplaces.

Pregnant Women and Family Planning Expansion Programs

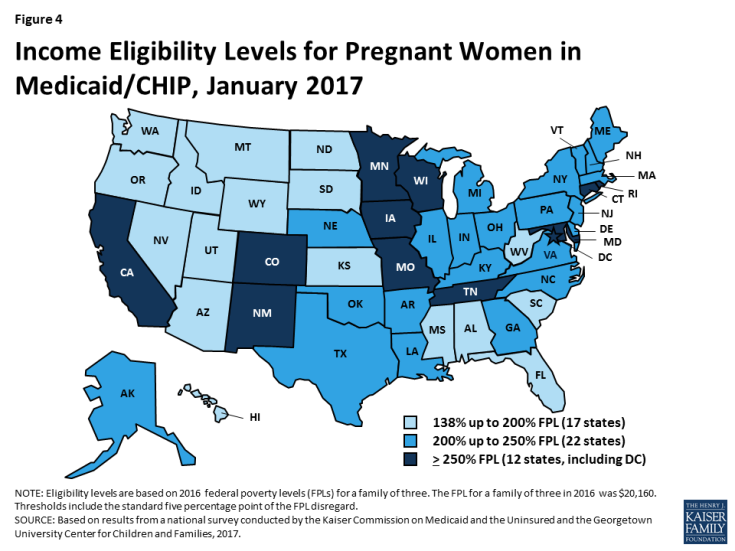

All states cover pregnant women with incomes up to at least 138% FPL, and 34 states cover pregnant women with incomes at or above 200% FPL as of January 2017 (Figure 4). Across states, eligibility for pregnant women ranges from 138% FPL in Idaho and South Dakota to 380% FPL in Iowa. Five states cover pregnant women through CHIP, and 16 states use CHIP funding to provide coverage through the unborn child option, under which states cover income-eligible pregnant women regardless of immigration status. Just under half of states (23 states) have taken up the option to cover lawfully residing immigrant pregnant women without a five-year waiting period. In addition, the District of Columbia, New Jersey, and New York use state-only funds to cover income-eligible pregnant women who are not otherwise eligible due to immigration status. During 2016, Michigan expanded Medicaid eligibility to pregnant women with incomes up to 400% FPL who were affected by the Flint water crisis. Missouri created a separate CHIP program for pregnant women with incomes between 201% and 305% FPL and adopted the unborn child option. Outside of these changes, Medicaid and CHIP coverage for pregnant women remained stable in 2016.

As of January 2017, over half of the states (29) have expanded access to family planning services through a waiver or the state option created by the ACA. States must provide family planning services as a covered benefit to Medicaid enrollees. Historically, some states also used waivers to provide family planning services to women or men who did not qualify for full Medicaid coverage. The ACA made a new option available for states to expand family planning services coverage. As of January 2017, 29 states have family planning expansion programs through a waiver or the state plan option.

Parents and Adults

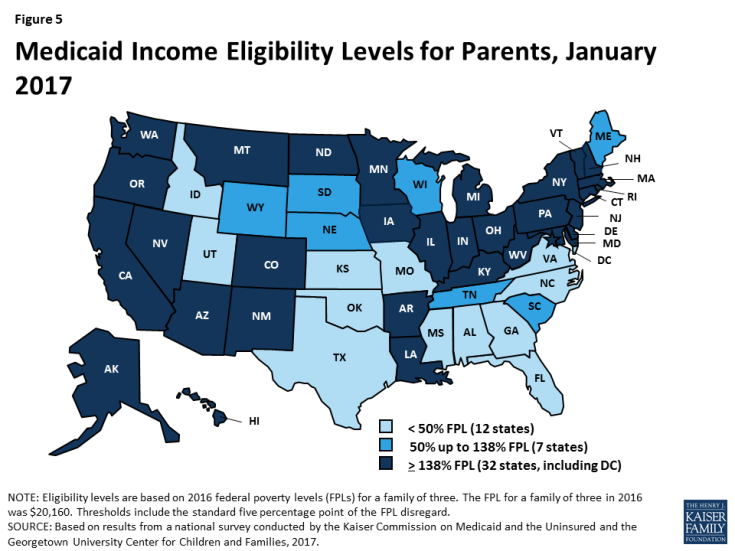

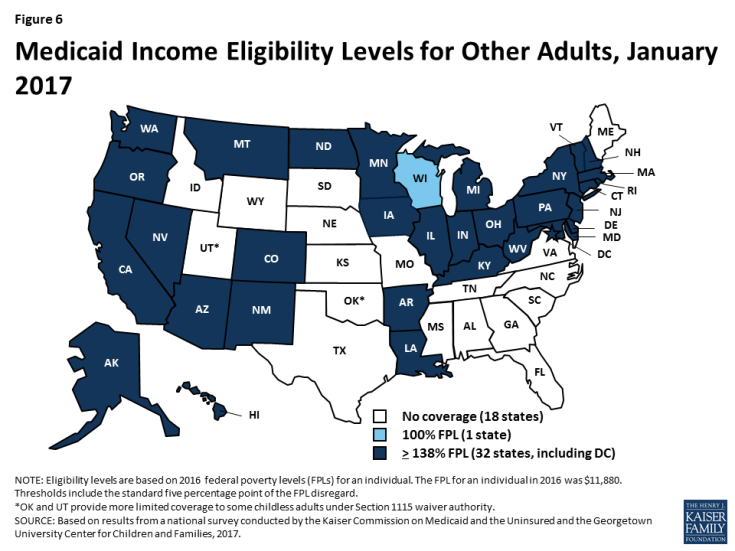

With Louisiana’s adoption of the Medicaid expansion during 2016, 32 states cover parents and other adults with incomes at up to at least 138% FPL as of January 2017 (Figures 5 and 6). Alaska, Connecticut, and the District of Columbia also extend coverage to parents and/or other adults with incomes above 138% FPL. In addition, two states, Minnesota and New York, have used the ACA Basic Health Program option to cover adults with incomes between 138% and 200% FPL, rather than having individuals in this income range access coverage through the Marketplace.

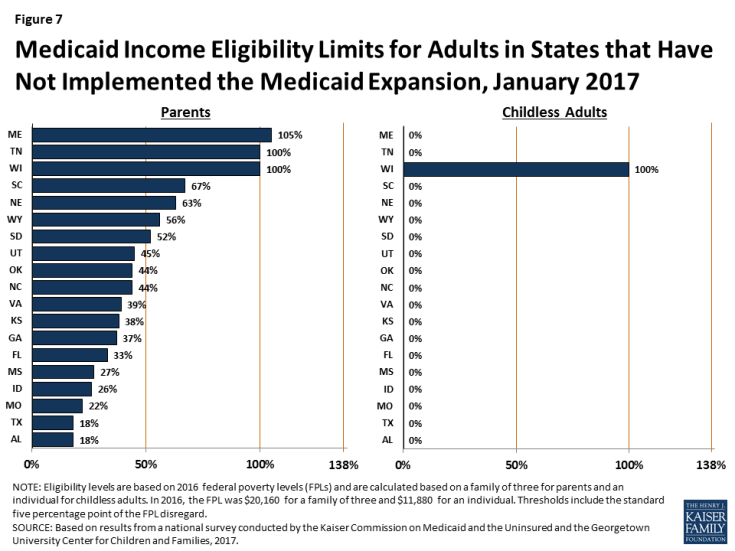

In the 19 states that have not expanded Medicaid, the median eligibility level for parents is 44% FPL, and other adults remain ineligible regardless of income, except in Wisconsin (Figure 7). Among the 19 non-expansion states, parent eligibility levels range from 18% FPL in Alabama to 105% FPL in Maine. Only 3 states—Maine, Tennessee, and Wisconsin—cover parents at or above 100% FPL, while 12 states limit parent eligibility to less than half the poverty level ($10,080 for a family of three as of 2016). Wisconsin is the only non-expansion state that provides full Medicaid coverage to other non-disabled adults, although its 100% FPL eligibility limit remains below the ACA expansion level and it does not receive the enhanced federal match for this coverage. While this study reports eligibility based on a percentage of the FPL, 13 non-expansion states base eligibility for parents on dollar thresholds (which have been converted to an FPL equivalent in this report). Twelve of these states do not routinely update the dollar standards, resulting in eligibility levels that erode over time relative to the cost of living. In non-expansion states, 2.6 million poor adults fall into a coverage gap.4 These adults earn too much to qualify for Medicaid, but not enough to qualify for subsidies for Marketplace coverage, which are available only to those with income at or above 100% of FPL.