In January 2025, President-elect Trump will be sworn in with Republican control of Congress and a conservative majority in the Supreme Court, which will potentially provide broad latitude for the adoption of a conservative agenda. Federal policymakers have many levers to make major changes that will shape the access and availability of reproductive health including abortion, contraception and maternity care in ways that could affect the whole nation, even in states where the right to reproductive health care is enshrined by the state constitution. In addition to enacting legislation, presidential executive orders, litigation, regulatory actions, and nominations to the judiciary, cabinet, and other leadership position appointments will all affect policy.

This brief reviews some of the possible actions of the incoming Trump administration and new Congress based on campaign statements, policies implemented by the first Trump administration, and proposals forwarded by allied conservative think tanks and antiabortion advocacy groups. While President-elect Trump has generally said in recent comments that he would leave abortion policy up to states, his statements at times leave open the possibility for federal changes, and he will likely come under pressure from outside groups and Congress to restrict abortion access.

Abortion

Trump takes credit for overturning Roe and has said that states should set their own abortion policy, including banning abortion. As President, he could support additional policies that would result in limits to abortion access in all states, even without enacting a national abortion ban.

Currently, 13 states ban abortion with very few exceptions and several other states limit abortion availability to early in pregnancy. While Trump has said that he would not sign a federal bill banning abortion in all states, there are many levers that an anti-abortion administration can use to severely limit abortion access. Project 2025 and other anti-abortion organizations and policymakers have outlined a clear agenda, with the goal of banning or severely restricting abortion, especially targeting medication abortion given its dominance as a method of abortion and the current FDA policy that allows for the mailing of abortion pills without the need for any in person contact with a clinician.

Abortion Access

Trump has given conflicting statements about whether he would support a national ban that would apply in all states. At times, he has suggested that he would support a nationwide ban at 15 or 16 weeks gestation, but also has said that he would not sign a national ban. He has said that he believes in exceptions for cases of rape, incest, and life of the mother, but has not forwarded a stance on health exceptions. In his recent comments, Trump has said he would leave abortion access up to states.

Enforcing the Comstock Act

Medication abortion pills account for the majority of abortions in the U.S. The Comstock Act is an 1873 anti-vice law banning the mailing of “obscene” matter and articles used to produce abortion. The Biden administration’s Department of Justice determined that the Act only applies when the sender intends for material or drug to be used for an illegal abortion, and because there are legal uses of abortion drugs in every state including to save the life of the pregnant person, there is no way to determine the intent of the sender. However, this analysis does not preclude the Trump administration from interpreting the Comstock Act differently. President-elect Trump’s statements about medication abortion have been inconsistent, at times suggesting he would not block their availability and decline to enforce the Comstock Act. Recently, Trump said he “probably” would not move to restrict medication abortion but added that “things change.” Some Republican leaders, including Vice president-elect Vance and the authors of Project 2025 —the detailed conservative policy treatise that was spearheaded by many former Trump administration leaders – have called for a literal interpretation and enforcement of the Comstock Act to halt the mailing of all abortion medications and supplies to all states. This would impact not only residents of states where abortion is banned or restricted but all states, even those that have a guaranteed right to abortion in their state constitutions.

FDA Review of Mifepristone

The new director of the FDA will have significant influence over drug approvals, restrictions, and the broader agenda and priorities of the FDA. President-elect Trump recently indicated he will probably not restrict access to medication abortion but left room to change his position. Project 2025 and other conservative groups are calling for the FDA to retract its approval of medication abortion pills. Short of reversal, they seek to revert to older FDA protocols and restrictions that would reduce the gestational period for medication abortion pills, prohibit telehealth appointments and access through pharmacies, which were approved after President Biden took office. These issues are at the core of a federal lawsuit against the FDA that has been brought by Republican states, which the Trump administration may not defend and could succeed in front of a conservative Supreme Court.

Project 2025 also calls on the FDA to ease the process for health care providers to report complications resulting from abortion pills to the FDA Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS). Although it’s not yet clear how the new director will address mifepristone, Trump’s nominee, Dr. Martin Makary, has stated that fetuses feel pain during an abortion between 15 and 22 weeks gestation, despite conclusive evidence by major medical organizations and systematic reviews that find that a human fetus does not have the ability to experience pain at that point in pregnancy.

Since the Dobbs ruling, there have been numerous cases of deaths and near-death experiences attributed to denials and delays in providing abortion care to people experiencing miscarriages and pregnancy-related emergencies. EMTALA is the federal law that requires hospitals to provide health stabilizing treatment to patients who present to their emergency rooms, and the Biden administration issued guidance reiterating that EMTALA applies to abortion care provided in the cases of pregnancy-related emergencies. The Biden administration defended this policy in an ongoing case, but the Trump administration could withdraw the current guidance and stop defending the Biden administrations’ policy, as recommended by Project 2025, which argues that emergency abortion denials are not a problem. President-elect Trump has not commented specifically on this issue. While Trump disavowed Project 2025 during the campaign, he has also announced appointments of a number of people tied to the effort since the election.

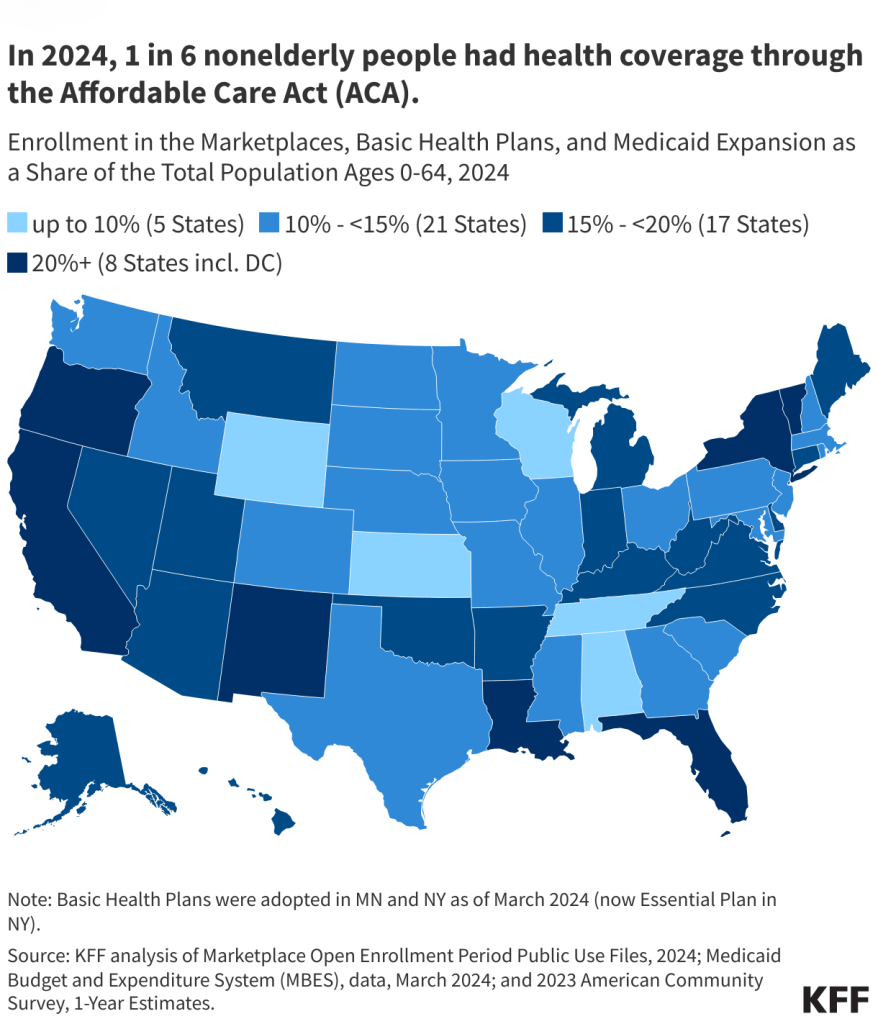

Coverage under Medicaid and ACA Marketplaces

The Hyde Amendment is a policy attached to the Congressional appropriations bill annually that bars the use of any federal funds for abortion, only allowing exceptions to pay for terminating pregnancies that endanger the life of the pregnant person or that result from rape or incest. While Trump has not spoken about the Hyde Amendment recently, he had earlier pledged to make it permanent law, as advocated by Project 2025. The report also urges policymakers to resurrect an earlier proposed Trump administration policy that would have required enrollees in ACA Marketplace plans to submit two separate payments if they choose a plan that includes abortion coverage.

Data and Research

The Trump administration could exert its influence over research and surveillance on abortion activities across multiple federal agencies. The Project 2025 report addresses abortion-related data collection and research. In particular, the report calls for CDC research on the risks of abortion, abortion survivors, and requiring reporting on the number of abortions from every state (currently voluntary) as a condition of receiving federal Medicaid funds. The plan details the need to collect data on abortion rates across various demographic groups, monitor the number of cases of infants born alive after abortions (which does not happen), abortion harms, and withhold HHS funds from states where abortion remains legal if they do not comply with these requirements. Any new requirement on states as a condition of receiving federal Medicaid funds will likely be challenged in the courts.

The new administration may also curtail scientific research and vaccine development by reinstating a previous Trump administration policy that barred NIH funding for projects that use of tissue and cell lines that are byproducts of abortions. Project 2025 characterizes this as “the destruction of human life” and a major breach of ethics that government should prohibit. It could also be used to build the case for establishing “fetal personhood” arguments that can be used to further embed abortion bans and restrictions.

There are a number of other administrative actions that were passed under President Biden that the Trump administration could revoke, including guidance that reinforced requirements for pharmacies to fulfill their obligation to provide access to reproductive health pharmaceuticals, enforcement of non-discrimination policies for health care providers, and rules that strengthened data privacy to protect those seeking reproductive health care.

Religious Refusals

Trump’s first administration prioritized expanding religious exceptions to the provision or coverage of certain health care services. During his first term, HHS created a Division on Conscience and Religious Freedom and proposed multiple policies that would expand religious exemptions for health care providers and payors. Additionally, CMS invoked the Weldon Amendment and threatened to withhold federal Medicaid dollars from California because of the state’s policy requiring abortion benefits in all state-regulated health plans. The amendment is attached annually to a federal spending bill, and bars HHS funds from going to programs or state and local governments that “discriminate” against plans, providers, or clinicians that refuse to provide, offer referrals for, pay for, or cover abortions.

Short of formally implementing policies, President-elect Trump and his advisors can sow confusion by the information and misinformation that they spread. For example, Trump has repeatedly stated that Democrats support abortion up to and after birth, which is false. Similarly, members of his circle of health care advisors have stated that abortion is “murder,” fetuses can feel pain, and suggested that abortion can cause cancer. All of these statements have been refuted by scientific and medical groups.

Contraception

President-elect Trump could reinstate policies that he implemented in his first term that resulted in the reduced availability of contraceptive care to low-income people through regulatory action that targeted the Title X federal family planning program. The Republican party platform states support for “access to birth control,” but a federal the Right to Contraception Act failed to pass Congress this year, due to opposition or abstention from the vast majority of the Republican Senators, including Vice President-elect Vance. Trump placed multiple restrictions on financing for contraception in his first term.

Title X Federal Family Planning Program

program if they also offered abortion services (with separate funding); additionally, they prohibited participating clinics from offering referrals to abortion services at other clinics to pregnant patients seeking abortion information. These changes resulted in a steep reduction of the network of clinics receiving federal support from the Title X program. His administration also provided federal family planning funding through Title X funds to crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs) that do not provide contraception, which had been a requirement of the program until that time. While the Biden-Harris administration reversed the Trump administration changes to the program, Project 2025 calls for the restoration of the Trump-era rules, focusing the program on fertility-awareness based methods (FABM), greater support for CPCs, and Congressional passage of a federal law that would prohibit participation from clinics that offer both contraception and abortion services such as Planned Parenthood.

The new Trump administration could either revoke or not enforce the long-standing Title X program’s requirement that Title X-funded clinics provide minors with confidential contraceptive services without parental consent or notification. As a result of recent litigation challenging the rule in Texas where there is a state parental consent requirement for minors, the Biden administration is not enforcing the confidentiality rule in Texas. There are also other states that require parental consent for contraceptive services for minors. The administration could also direct more federal funds toward abstinence education, as they did during Trump’s first term.

Medicaid and Family Planning

Disqualifying Planned Parenthood clinics and other providers that offer both contraception and abortion care from the Medicaid program has long been a priority of some Republican lawmakers and conservative organizations, despite a current federal Medicaid requirement to include all willing providers in the program. Medicaid covers about one in five non-elderly adult women, and is an important source of payment for many family planning providers. For decades, the program has required coverage for contraceptives and other family planning services. In his first term, Trump allowed federal Medicaid funds to be used in a Texas Family Planning Medicaid waiver program that excluded Planned Parenthood and explicitly excluded emergency contraception (EC), which prevents pregnancy after sex by preventing or delaying ovulation. The second Trump administration could approve similar waivers from more states.

For wider-reaching impact, the new Republican Congress could pass legislation stipulating that federal funds to states may not go to entities that provide abortion services, even if the funds are used to pay for non-abortion care. This proposal was included in Republican-sponsored bills that aimed to repeal and replace the ACA in 2017.

Contraceptive Coverage and the ACA

Private insurance coverage for contraceptives and other evidence-based preventive services such as cancer screenings and prenatal care is required under the ACA, but a pending federal lawsuit, Braidwood Management Inc v Becerra, challenges some of these requirements. It is unknown if Trump will fight this case and defend the ACA requirement. Project 2025 calls for the federal government to issue new requirements for contraceptives and other women’s preventive services because of the pending case. In addition, the Biden-Harris administration recently issued a proposed regulation that would require coverage of over-the-counter contraceptive methods without the need for prescription and would re-define how contraceptives are classified for coverage purposes, potentially expanding the scope of methods that would be required to be covered by plans without cost-sharing. It is unclear if the Biden-Harris administration will finalize the regulation and how Trump will approach the issue.

Maternal Health

During the 2024 campaign, President-elect Trump stated that he would provide full coverage for in vitro fertilization (IVF), which would require Congressional action.

IVF

During the campaign, Trump said that if elected, his administration would provide access to full coverage of IVF services by requiring insurance companies or the government to pay, but he has not provided any details on how this would be funded or operationalized. While Trump says he supports IVF, there is disagreement among conservative circles. The official Republican party platform express support for IVF, but also invokes the 14th Amendment, which can be used to promote fetal personhood policies that could potentially threaten and criminalize IVF care. Additionally, the Project 2025 authors refer to embryos as “aborted children” and oppose research using embryonic stem cells (which can be derived from the IVF process). In the past year, Republican Senators blocked federal legislation that would have established a federal right and coverage of IVF.

Maternal Mortality and Morbidity

The state of maternal health, particularly pregnancy-related mortality, morbidity, and wide racial and ethnic disparities, remains a major health concern, and at times policymakers across party lines have advanced policies to try and improve maternal health. The pregnancy-related mortality rate in the U.S. is 33.2 per 100,000 live births – the highest of any developed country – resulting in over 1,000 deaths in 2021. The first Trump administration issued a maternal health plan near the end of his term and he signed federal legislation that provided funding for maternal mortality review committees. Doula care has been forwarded as a promising approach to support pregnant people, particularly those who are at risk for adverse maternal and infant birth outcomes. This could be an area that garners some bipartisan interest. The Project 2025 document supports broader access to doulas, with the caveat that no federal funds be used to support training related to abortion care. Some states already cover doula services under Medicaid, but implementation of these benefits has been limited and challenging in many cases.