Elimination of Federal Diversity Initiatives: Implications for Racial Health Equity

As one of his first actions in office, President Trump signed executive orders revoking federal diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) related programs and actions in the federal government and among federal contractors and grantees. DEI initiatives are intended to create more diverse and inclusive work environments, to address discriminatory policies or practices, as well as to counter the impacts of historical actions that led to unequal opportunities for certain groups. In implementing President Trump’s executive orders, the administration has taken significantly broader actions beyond eliminating DEI programs to include eliminating priorities, actions, information, data, and funding related to concepts of diversity or disparities among federal agencies as well as federal contractors and grantees. Some of these actions have been paused due to ongoing litigation, and it remains to be seen what actions may proceed under final court rulings. Given the broad nature of these actions, they will not only likely lead to a less inclusive and diverse workforce, including in health care, but will also likely lead to widening disparities in health and health care, reversing prior efforts to address disparities and advance equity.

This brief explains the potential impacts of the elimination of diversity and disparities-related initiatives under the Trump administration on racial health disparities. While this brief focuses on racial and ethnic disparities, these actions have implications for health equity across other dimensions, including gender and sexual orientation. The terms DEI and DEIA are similar and often used interchangeably. The “A” in DEIA refers to accessibility for people with disabilities. The remainder of this brief uses DEI as it is more commonly known and used, but with the recognition that accessibility is also a key part of health equity

Federal Actions to Eliminate Disparities Initiatives

On the first day of his second term, President Trump signed Executive Order 14148 which revoked 78 executive orders and memoranda issued by the Biden administration, many related to DEI. This included President Biden’s Executive Order 13985, which required federal agencies to conduct equity assessments and collect data to track and address trends and barriers that underserved communities face in accessing federal positions and programs. The reversal also eliminated DEI frameworks that prioritized equity-driven decision-making and resource allocation in agencies such as the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

President Trump also issued Executive Order 14151 and directives that mandate federal agencies to terminate all DEI related offices and positions; equity action plans, actions, initiatives or programs; equity-related grants or contracts; and DEI performance requirements for employees, contractors, or grantees. In addition, he issued Executive Order 14168 to “recognize two sexes, male and female;” specify that sex shall refer to a biological classification of male or female; direct federal agencies and employees to only use “sex” and not “gender;” remove all references to “gender ideology” or identity; and ensure that grant funds do not promote “gender ideology.” Further, he signed Executive Order 14173, which revoked the 1965 Equal Employment Opportunity rule that protected against discrimination in employment among federal contractors; the order also added new requirements for federal contractors and grantees to certify that they do not operate DEI programs that violate anti-discrimination laws and for federal agencies to identify entities, including publicly traded corporations, large nonprofit corporations or associations, and foundations, to target with civil investigations to deter DEI programs. Other actions include Executive Order 14224, which named English as the official language of the U.S. and rescinded an executive order and guidance that reaffirmed the federal government’s commitment to make services accessible to people with limited English proficiency, as well as guidance directing schools and other entities that receive federal funds from the Department of Education to stop using “racial preferences.” This guidance broadens the landmark 2023 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that effectively ended the use of race-conscious admissions policies in higher education, overturning decades of precedent supporting affirmative action.

To carry out the executive orders, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) directed agencies and departments to take down all outward facing media that “inculcate or promote” “gender ideology,” as well as to remove all public facing DEI related websites and content. This resulted in the temporary shutdown of websites and removal of key health datasets. While some web pages and datasets began returning in several days, they included a warning message that they were being modified to comply with President Trump’s executive orders and some materials, such as codebooks and questionnaires, did not immediately return. The administration also directed departments and agencies to pause grants provided to federal contractors to identify and review programs and activities for consistency with the President’s policies. Reports also indicate that the administration has flagged over 100 words that federal agencies should limit or avoid to comply with the President’s policies, including disparities, diversity, equity, and race. The CDC reportedly ordered the withdrawal of papers pending publication to ensure language compliance. Similarly, reports suggest that the National Science Foundation froze payments to grantees and began screening grant proposals for terms related to gender, equity, and inclusion and that the National Institutes of Health began terminating research grants to comply with the new restrictions.

Multiple lawsuits have been filed challenging the executive orders and actions, which have halted some of these actions, but it remains to be seen what actions will be allowed under final court rulings. For example, a preliminary nationwide injunction blocked enforcement of significant provisions of the executive orders, including the termination of federal contracts and funding. Other litigation has ordered the return of public health web pages and datasets. Some of this information has been restored, such as the FDA’s draft guidance on diversity in clinical trials, but with an explanatory note that any information on the page promoting “gender ideology” is “extremely inaccurate” and that “Administration and this Department reject” the content:

Per a court order, HHS is required to restore this website as of 11:59 PM on February 11, 2025. Any information on this page promoting gender ideology is extremely inaccurate and disconnected from the immutable biological reality that there are two sexes, male and female. The Trump Administration rejects gender ideology and condemns the harms it causes to children, by promoting their chemical and surgical mutilation, and to women, by depriving them of their dignity, safety, well-being, and opportunities. This page does not reflect biological reality and therefore the Administration and this Department reject it.

Source: FDA

Implications for Health and Health Equity

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and racial reckoning following the murders of George Floyd and others, the federal government as well as many states and private entities increased efforts focused on addressing health disparities, including recognizing the role of historical and ongoing racism in driving disparities. This increased focus led to the development of programs and initiatives focused on mitigating disparities, including efforts to address disparities in maternal and infant health, cancer, and chronic disease, as well as other efforts, such as increasing diversity in clinical trials for development of new drugs and devices. Research efforts also increased to understand disparities, the factors driving them, and effective interventions to mitigate them. Implementation of President Trump’s executive orders eliminates much of this work, which will likely lead to widening disparities in health.

Elimination of focused efforts to address health disparities will potentially further exacerbate disparities, contributing to worsening overall health and unnecessary health care costs. To comply with the President’s executive orders, federal agencies have eliminated health equity plans, strategies, and guidance focused on mitigating disparities. For example, the administration ordered the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to disband its Health Equity Advisory Committee, which was charged with addressing systemic barriers to access that included structural racism, and Federal Drug Administration draft guidance on diversity in clinical trials (although it was restored pursuant to a court order). Focused plans and initiatives to mitigate health disparities seek to address the underlying inequities that drive disparities and meet the needs and preferences of diverse populations. These efforts are important for equity and for improving the nation’s overall health and economic prosperity. Racial and ethnic health disparities result in higher rates of illness and death across a wide range of health conditions. Research also shows that disparities are costly, resulting in excess medical care costs and lost productivity, as well as economic losses due to premature deaths. In the absence of focused efforts, disparities will likely widen because the underlying inequities that contribute to them persist, leading to worse overall health and unnecessary health care costs.

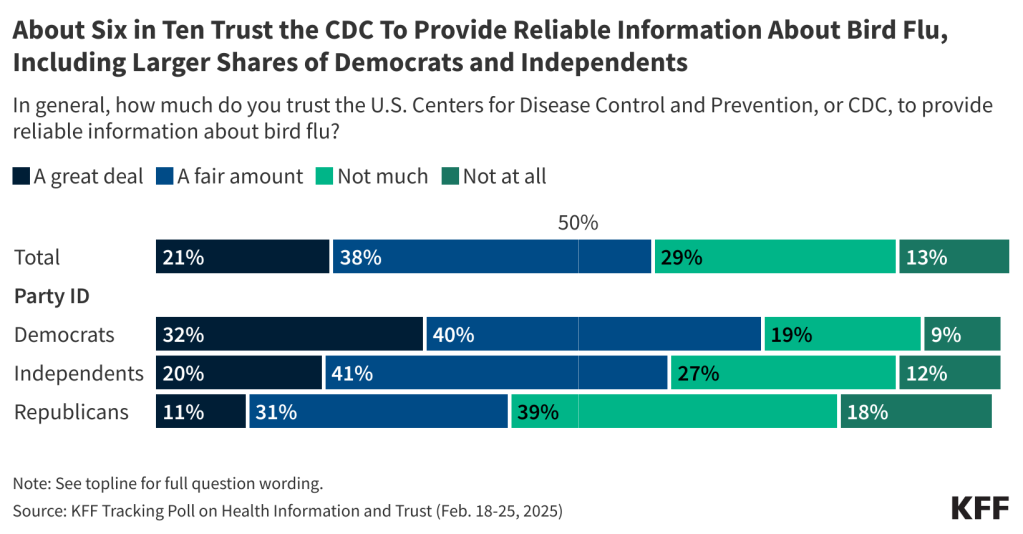

Loss of information, data, and research will inhibit the ability to identify disparities and understand the factors driving them. In implementing the executive orders, agencies removed health information, such as HIV-related content, and reports on current disease threats, like bird flu, as well as federal data, including data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Census. While some of the datasets were returned, they were marked with a warning message suggesting there could be future changes, leaving uncertainty about what data will be available over the long-term. Additionally, as noted, federal agencies are now screening and halting research related to disparities, equity, and inclusion, which will likely lead to reductions in funding to support research on disparities. Data are a cornerstone for efforts to address health disparities and advance health equity. Data are essential for identifying where disparities exist, directing efforts and resources to address disparities as they are identified, measuring progress toward achieving greater equity, and establishing accountability for achieving progress. Without adequate data and research disparities may remain unseen and unaddressed.

Elimination of DEI efforts among the federal workforce and contractors as well as in education will likely lead to a less diverse health care workforce, which would contribute to widening disparities in health care experiences and outcomes. People of color have historically been underrepresented in the health care workforce relative to their share of the population. Research shows that increasing the racial and ethnic diversity and cultural competency of health professionals is associated with improved access to care, greater patient choice and satisfaction, and other benefits. KFF 2023 survey data show Black, Hispanic, and Asian adults who have more health care visits with providers who share their racial and ethnic background report more frequent positive and respectful interactions. Other research suggests that patient and provider racial concordance contributes lower emergency department use, increased visits for preventative care, and greater treatment adherence. One study found that greater representation of Black primary care physicians led to increased life expectancy and lower mortality among Black people. The recent actions to eliminate diversity efforts among federal agencies and contractors as well as in education will likely reverse progress diversifying the health care workforce. For example, research suggests that the 2023 Supreme Court ruling banning affirmative action resulted in a decline in Black, Hispanic and American Indian and Alaska Native medical school students. Moreover, it remains unclear whether hospitals and providers are considered federal contractors subject to the executive orders to eliminate DEI-related activities, but there are concerns about the potential impact to hospital hiring, training, and programming.

Elimination of diversity efforts will lead to a less diverse and inclusive workforce among federal agencies and contractors with fewer protections against discrimination. The new executive orders undo longstanding policies that grew out of antidiscrimination laws focused on increasing employment opportunities for historically underrepresented groups in the federal government and among federal contractors. It reverses efforts by President Biden to strengthen the federal government’s ability to “recruit, hire, develop, promote our nation’s talent and remove barriers to equal opportunity.” Reports suggest that DEI initiatives can support talent acquisition and performance. Prior analysis from the Office of Personnel Management, which has since been removed from the web, found that the federal government achieved significant declines in the gender pay gap for women over time and has a much smaller gap compared to the national gap. Without diversity efforts, certain groups may face increased barriers to employment and advancement, which has impacts for health care access and health.

Federal actions to eliminate diversity and disparities-related efforts are having ripple effects in the private sector, schools, and states. As part of federal actions to eliminate DEI efforts, the federal government issued a statement that they will “investigate, eliminate, and penalize illegal DEI and DEIA preferences” at private companies and universities that receive federal funds. Reports show a wide range of private companies ending or reframing DEI related initiatives in the last several months as well as reversal of DEI efforts in universities and schools. Some states also are reversing or prohibiting DEI-related work, including efforts that began prior to President Trump taking office. In 2024, state legislatures introduced over 30 bills aimed at restricting DEI initiatives in public colleges and universities. Some states also have imposed limits on teaching concepts related to systemic racism, historical inequities, and unconscious bias.