To Switch or Not to Switch: Are Medicare Beneficiaries Switching Drug Plans To Save Money?

STUDY HIGHLIGHTS

Each year during the Medicare Part D annual enrollment period that runs between October 15 and December 7, people on Medicare have the opportunity to review and compare the plan options available to them and switch plans if they choose. This analysis examines rates of plan switching among Part D enrollees between 2006 and 2010, focusing on enrollees who do not receive the program’s Low-Income Subsidy. The study finds that relatively few people on Medicare have used the annual opportunity to switch Part D prescription drug plans (PDPs) voluntarily—even though those who do switch often lower their out-of-pocket costs as a result of changing plans. Key findings from this study are:

- A small share of all Medicare Part D enrollees voluntarily switch plans during the annual enrollment period—13 percent, averaged across four enrollment periods.

- Seven out of ten Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in stand-alone PDPs during all four annual open enrollment periods from 2006 to 2010 did not voluntarily switch plans in any of the four enrollment periods.

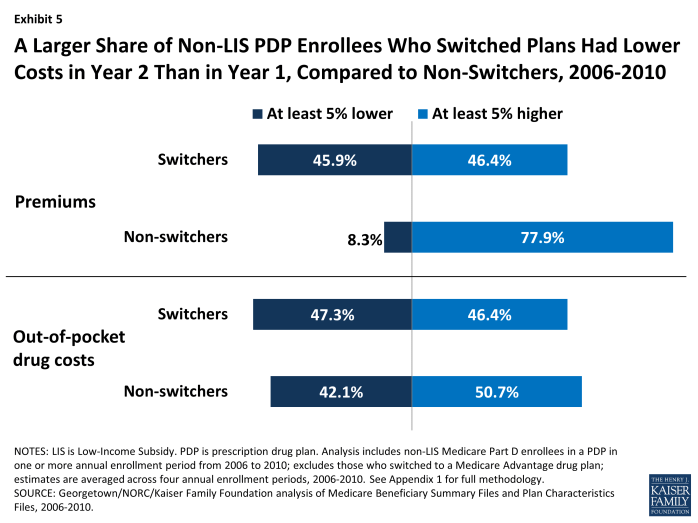

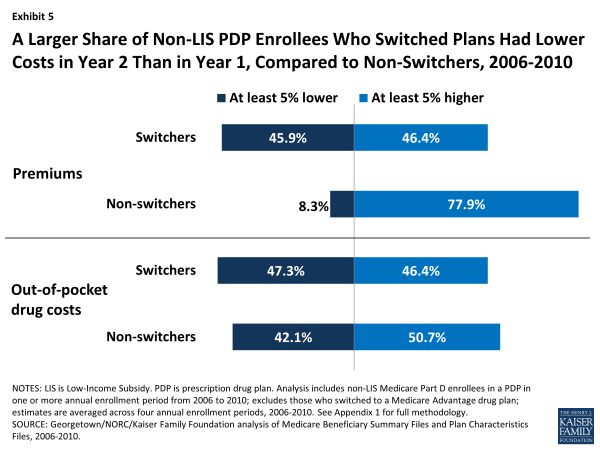

- The relatively small share of PDP enrollees who switched plans at some point between 2006 and 2010 were more likely than those who did not switch to end up in a plan that lowered their premiums. Nearly half (46 percent) of enrollees who switched plans saw their premiums fall by at least 5 percent the following year, compared to 8 percent of those who did not switch plans. But those who switched plans were only slightly more likely than those who did not switch to face lower out-of-pocket costs for drugs during the year.

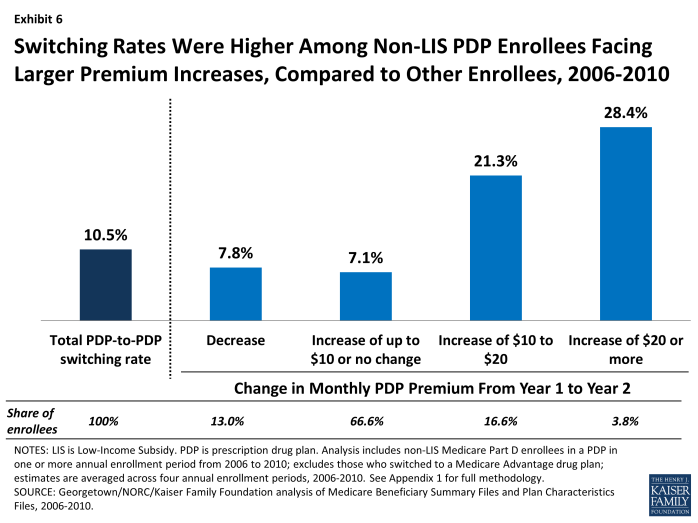

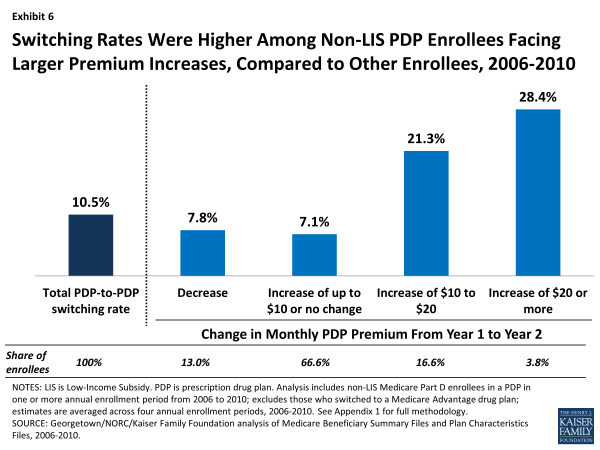

- Relatively large premium increases for a PDP from one year to the next were associated with higher rates of plan switching between 2006 and 2010; but most enrollees with relatively large premium increases (such as $10 or more per month) did not switch plans in any of the four annual enrollment periods.

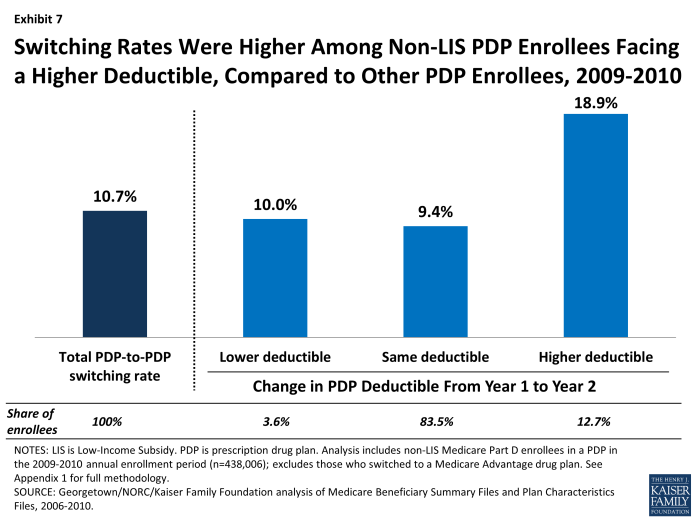

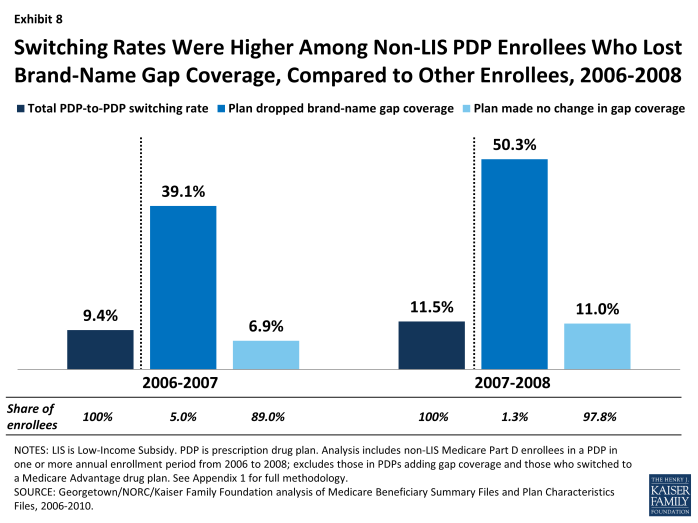

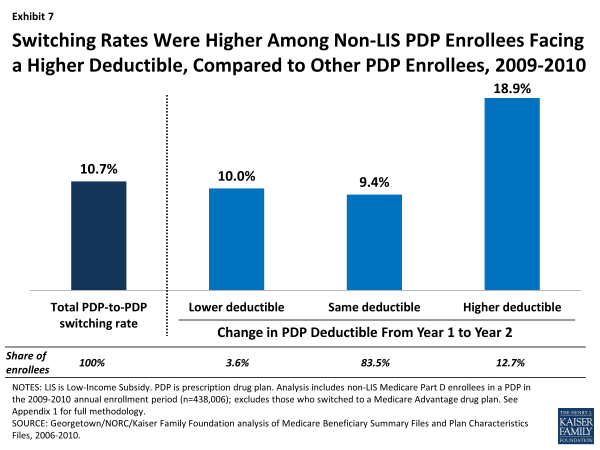

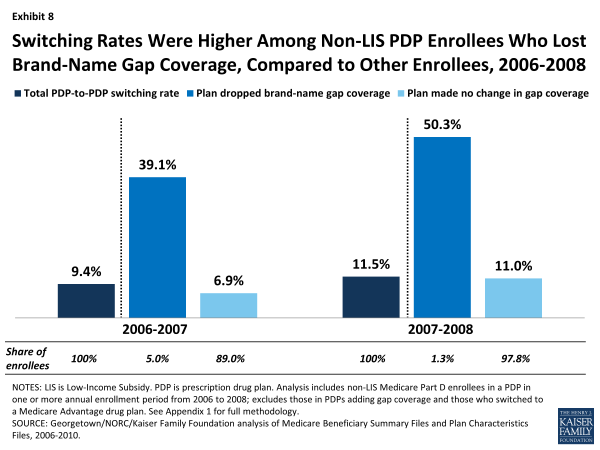

- Enrollees in PDPs that increased deductibles or dropped coverage of brand-name drugs in the coverage gap were more likely to switch out of these plans than enrollees in PDPs that did not change their benefit design.

.

INTRODUCTION

The Medicare Part D program is structured as a marketplace for prescription drug coverage where all Medicare beneficiaries must be enrolled in a private plan to receive Medicare’s prescription drug benefit. Ideally, beneficiaries will research the array of available drug plans and choose the one that best meets their needs, and further review and compare their options each year during the annual open enrollment period. The annual open enrollment period provides Part D enrollees with an opportunity to review any changes in their current plan, compare the coverage and costs of plans in their area in light of their current drug needs, and assess whether or not to stay in their plan or switch to another plan that would cover the drugs they need at a lower cost. In general, unless enrollees make an active choice to switch plans, they will remain in the same plan from one year to the next.1

The Part D program, which started in 2006, has reduced the share of Medicare beneficiaries without drug coverage, and provided beneficiaries a choice among many plans offered in their area. In 2013, for example, the average Part D enrollee has a choice of 31 stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) and about 20 Medicare Advantage prescription (MA-PD) drug plans.2 Part D plans vary in a number of ways that can affect beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs, including premiums, cost-sharing amounts, formulary coverage, gap coverage, deductibles, and utilization management approaches. To assist people on Medicare with comparing and choosing plans, CMS offers an online Plan Finder tool that calculates the expected total cost for any plan for a given drug regimen.

Only a small fraction of enrollees, however, are enrolled in the lowest-cost Part D plan available to them, based on the specific drugs they take.3 Therefore, many Part D enrollees incur higher out-of-pocket costs than would be the case with a different plan selection. This is true especially in situations where the plan premium is not a good indicator of overall value, such as plans that include coverage for generic drugs in the coverage gap or plans with no deductible.4 Part D enrollees often have difficulty with the plan selection process and find the decision-making complicated, especially because of the large number of available plans.5

Each year, Medicare Part D plans can and do make changes in their premiums and in benefit design parameters that affect the total out-of-pocket costs enrollees will pay. While some plans make changes that reflect broad trends in the Part D market, other plans make changes (such as premium increases well above the overall trend) that affect their position in the marketplace. Yet, in a recent survey, only six in ten seniors said they (or someone on their behalf) review their plan options every year; one-fourth said they rarely or never do so.6 Some plan enrollees could be better off financially by reacting to these changes and selecting a different plan, and not doing so can increase the cost difference between the chosen plan and other available alternatives. According to one recent paper, the combined impact of inertia for those staying put and suboptimal choices made by those who do change plans means that the cost of not engaging in the plan review process at all or not choosing the highest-value plan has increased over time.7

This purpose of this study is to determine the extent to which Part D enrollees voluntarily switch plans from one year to the next, and to identify plan and beneficiary characteristics that are associated with higher or lower rates of switching. The study examines enrollment dynamics in Part D during the annual enrollment periods between 2006 and 2010 for beneficiaries who are not enrolled in the program’s Low-Income Subsidy (LIS), focusing primarily on enrollees in stand-alone PDPs. We exclude LIS enrollees entirely and MA-PD plan enrollees from most of the analysis because the enrollment dynamics and factors affecting plan switches are different for these two markets and populations.8 Our study makes a unique and important contribution to understanding of the Part D marketplace because it is the first to take an in-depth look at enrollment dynamics across multiple years since the start of the program and examine plan features associated with higher rates of plan switching. In doing so, it goes beyond the analysis recently published by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC).9 These findings have implications for efforts to increase the level of private plan participation in the broader Medicare program.

.

DATA AND METHODS

The analysis for this study is based on a 5-percent random sample of Medicare beneficiaries, obtained from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), for each year from 2006 to 2010. The sample dataset includes information on the characteristics of beneficiaries and Part D plan information (encrypted at the level of the contract ID and plan ID).

From the five one-year samples, we matched non-LIS beneficiaries across years to build samples of beneficiaries who were enrolled in Part D for each of four two-year periods (2006-07, 2007-08, 2008-09, and 2009-10) and another sample of beneficiaries who were enrolled in the program for the entire 2006-10 period. For the analysis of overall switching rates, sub-samples were created for those who were enrolled in a PDP in the first year of each two-year cycle and those in a MA-PD plan in the first year; most of the analysis reported here uses the PDP sample. For the analysis examining the impact of plan characteristics, we further subset the two-year samples to include only PDP enrollees who remained in a PDP in the second year. Similarly, the five-year sample was restricted to those in PDPs the entire time.

In each two-year sample, we define a plan switch based on enrollment in a different plan in January of the second year, compared to December of the first year, thus focusing on changes in the annual enrollment period; switches in the five-year sample were defined similarly. We do not count plan switches that are involuntary under the following two circumstances: (1) a plan enrollee whose plan changes, but the old plan and the new plan are matched (“crosswalked”) by the plan sponsor, and the enrollee is therefore automatically transferred to the crosswalked plan; and (2) a plan enrollee whose plan exits the program without any crosswalked plan and who therefore must select a new plan to remain in Part D.

For a more detailed discussion of the data and methods, including other limitations, see Appendix 1: Study Methodology. Findings on the impact of individual enrollee characteristics (age, sex, race,10 original reason for Medicare entitlement, and geographic location), measures of beneficiary health status (number of chronic conditions and total Medicare expenditures), and drug spending are available in Appendix 2: Data Tables.

.

KEY FINDINGS

A small share of all Medicare Part D enrollees voluntarily switch plans during the annual enrollment period.

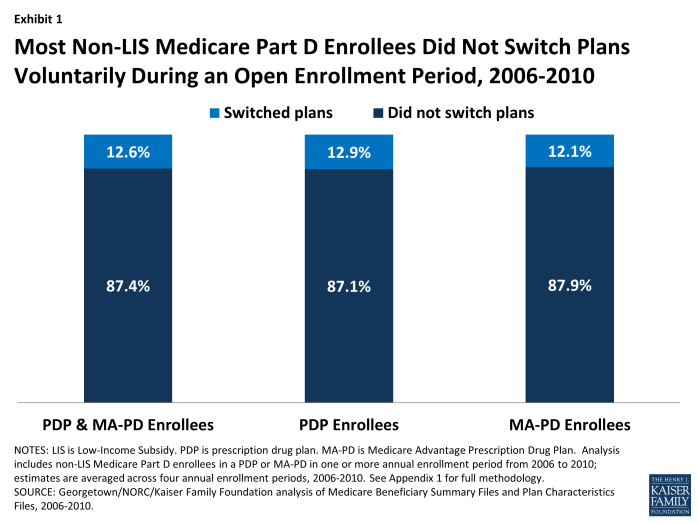

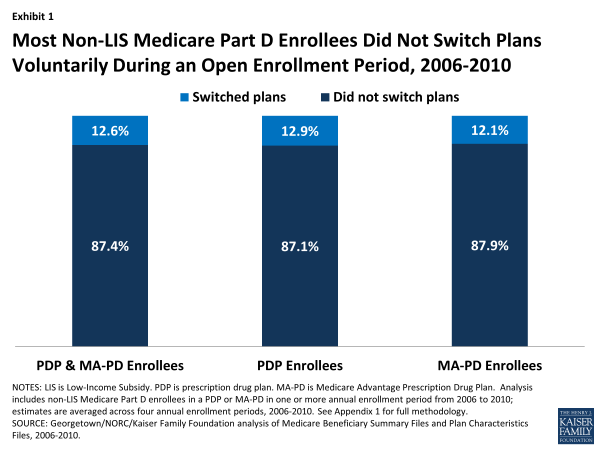

Most Part D enrollees (87 percent, averaged across four enrollment periods), whether in PDPs or MA-PD plans, made no change in their selected plan during any particular year’s annual enrollment period (Exhibit 1).11 Despite the fact that plans typically adjust premiums each year and some also make substantial changes to their benefit designs (gap coverage, deductibles, cost sharing, and formulary coverage), most beneficiaries do not change their current plan. On average, about 1.7 million Part D enrollees out of 13.4 million non-LIS Part D enrollees switched plans voluntarily in each annual enrollment period between 2006 and 2010.

Most Non-LIS Medicare Part D Enrollees Did Not Switch Plans Voluntarily During an Open Enrollment Period, 2006-2010

The percent of enrollees staying in the same plan from one year to the next was nearly the same for PDPs and MA-PD plans (Exhibit 1). Of those beneficiaries enrolled in stand-alone PDPs in any given year between 2006 and 2010, the vast majority (87 percent, on average) stayed in the same PDP from one year to the next. A virtually identical share of beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage prescription drug plans during these years (88 percent, on average) stayed in the same MA-PD plan from one year to the next.

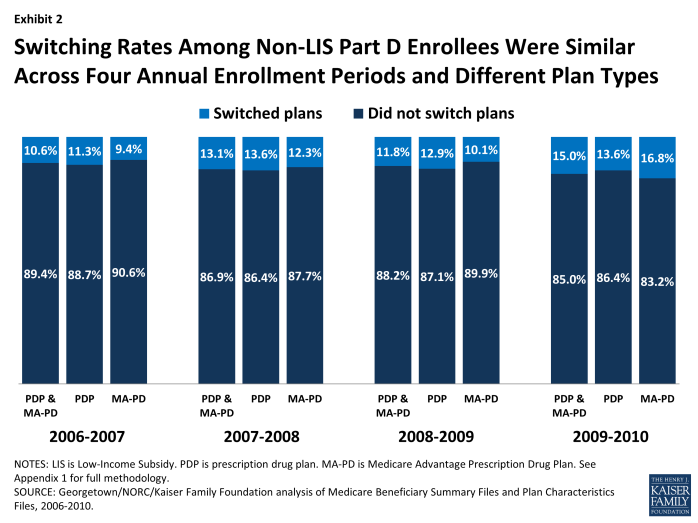

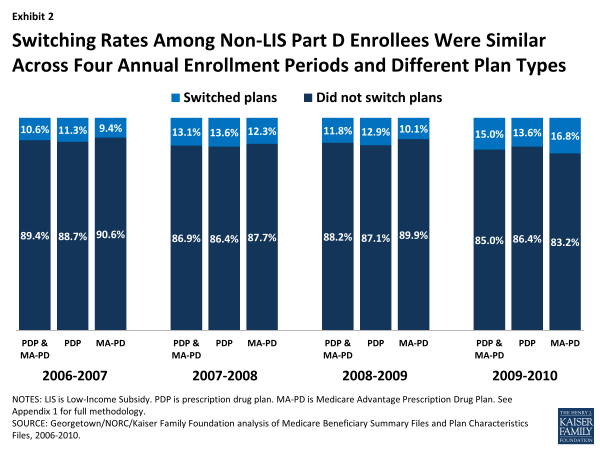

Switching rates have varied little from year to year (Exhibit 2). There was slightly greater stability in the first annual enrollment period (2006-07), perhaps because it came soon after the original selection of drug plans. There was slightly more switching among MA-PD enrollees in 2010, which may reflect changes unique to the Medicare Advantage market unrelated to the drug benefit, including changes in the availability of private fee-for-service plans.12

Switching Rates Among Non-LIS Part D Enrollees Were Similar Across Four Annual Enrollment Periods and Different Plan Types

There were relatively few differences in the rate of switching by beneficiary characteristics. For example, women switched plans slightly more often than men, and those with more chronic health conditions or with higher drug spending were somewhat more likely to switch plans. Enrollees ages 64 to 74 were slightly more likely to switch than those ages 85 and older. But the observed differences in switching rates based on these characteristics are small and not always consistent from one annual enrollment period to the next. Switching rates varied more across PDP regions, ranging from nearly 20 percent, on average, in the New Jersey and Pennsylvania-West Virginia regions to about 5 percent in New Mexico and Hawaii. The participation of local PDPs and the presence of state pharmacy assistance programs could be partial factors in explaining regional differences. Tables illustrating these comparisons are available in Appendix 2.

Seven out of ten Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in stand-alone PDPs during all four annual open enrollment periods from 2006 to 2010 did not voluntarily switch plans in any of the four enrollment periods.

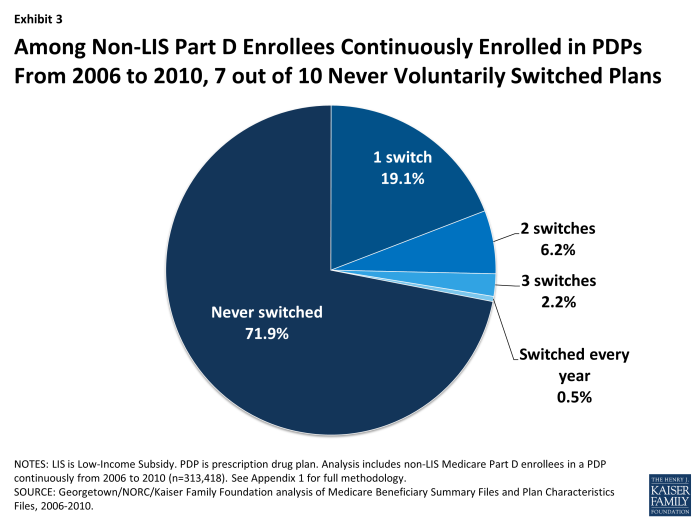

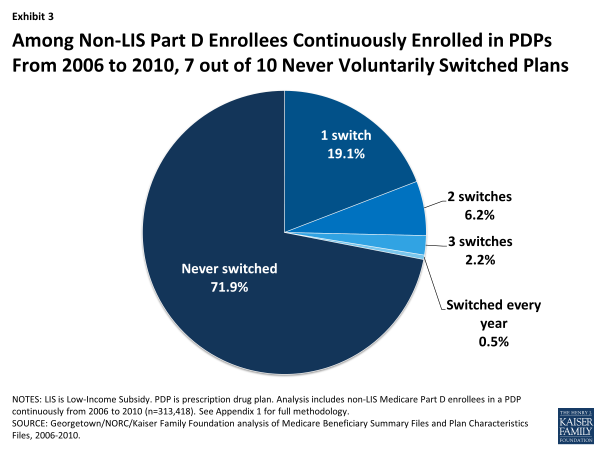

A large majority (72 percent) of Part D enrollees who were in PDPs continuously over the program’s first five years made no voluntary switch in any of the program’s first four annual enrollment periods (Exhibit 3).13 Another two in ten (19 percent) switched once over the five-year period. A similarly large share (71 percent) of MA-PD plan enrollees never made a switch in any of the enrollment periods.

Among Non-LIS Part D Enrollees Continuously Enrolled in PDPs From 2006 to 2010, 7 out of 10 Never Voluntarily Switched Plans

Of the five-year Part D enrollees who did switch PDPs at least once during the four enrollment periods, about two of every three made only a single switch. A small subset of PDP enrollees (about 3 percent) made frequent use of the opportunity to select a new PDP by switching plans in at least three of the first four annual enrollment periods, if not every year.

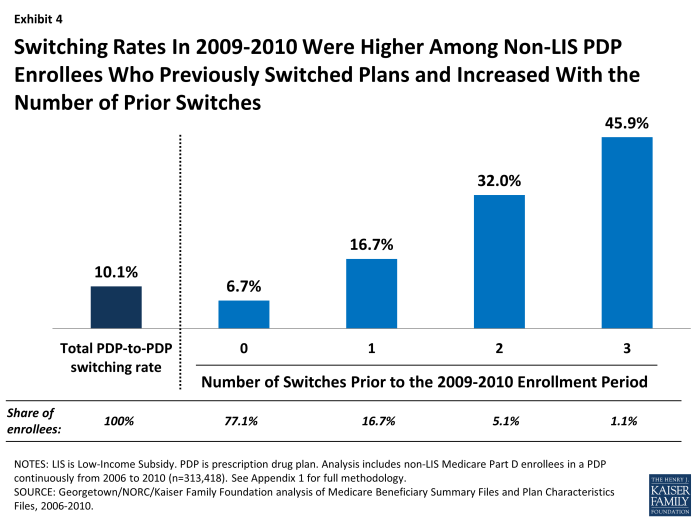

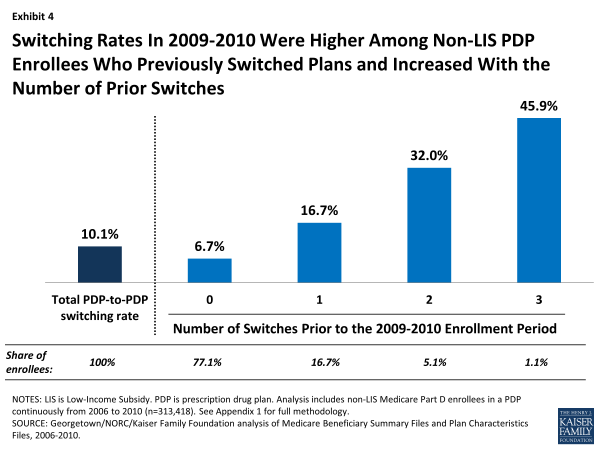

PDP enrollees were more than twice as likely to select a different PDP if they had made a switch in at least one previous year (Exhibit 4). Nearly one in five (17 percent) PDP enrollees who had switched plans in one previous annual enrollment period switched plans in 2010, compared to only 7 percent of PDP enrollees who had not switched in any previous enrollment period. Nearly half (46 percent) of those with three prior switches, and one-third (32 percent) of those with two prior switches, again chose a new PDP in 2010.

Switching Rates In 2009-2010 Were Higher Among Non-LIS PDP Enrollees Who Previously Switched Plans and Increased With the Number of Prior Switches

It is not possible to tell from administrative data how many enrollees who did not switch plans researched their options and made an active decision to stay in their original plan. However, these results suggest that some Part D enrollees are more engaged than others in reviewing their plan options every year and making active decisions about their plan choices.

The relatively small share of PDP enrollees who switched plans at some point between 2006 and 2010 were more likely than those who did not switch to end up in a plan that lowered their costs.

Those PDP enrollees who switched to a different PDP tended to face lower costs as a result, yet the effect was greater in terms of reducing the amount they spent on premiums than reducing their total out-of-pocket costs (Exhibit 5). Both switchers and non-switchers alike may face changes in their premiums from one year to the next. During the 2008 annual enrollment period, for example, 92 percent of PDP enrollees faced higher premiums in 2009 if they did not change PDPs, and 27 percent faced an increase of at least $10 per month.14 Our analysis shows that 46 percent of those who switched plans (averaged across the four annual enrollment periods) reduced their premiums by 5 percent or more as a result of switching, whereas only 8 percent of those who did not switch plans experienced the same reduction in their premium. Conversely, 78 percent of those who did not switch plans paid a premium at least 5 percent higher than the year before, compared to only 46 percent of those who did switch plans.

A Larger Share of Non-LIS PDP Enrollees Who Switched Plans Had Lower Costs in Year 2 Than in Year 1, Compared to Non-Switchers, 2006-2010

By contrast, PDP enrollees who switched plans were only slightly more likely than those who did not switch to experience a reduction in the amount they paid out of pocket for drugs during the year (Exhibit 5). In the second year, 47 percent of switchers, compared to 42 percent of non-switchers, lowered their out-of-pocket drug costs (including deductibles, copayments, coinsurance, and costs in the gap, but not premiums) by at least 5 percent. Differences in formularies or cost sharing—whether in a continuing plan or a new plan—were one reason for changes in these costs, but costs also rise and fall as a result of the need for different drugs from one year to the next. If switchers were more likely than non-switchers to experience changes in their prescription drug needs, it would bias this comparison.

Based on a combined measure of total out-of-pocket spending, including premiums and cost sharing for drugs, 44 percent of switchers had overall costs that were at least 5 percent lower, whereas only 28 percent of non-switchers experienced the same level of cost reduction.

The findings from these comparisons are consistent with a conclusion that Part D enrollees achieved lower costs when they selected a different plan during the annual enrollment period. But the findings also suggest that plan choice is driven more by premium changes than by a comparison of total out-of-pocket costs. At least two other recent studies have used Part D administrative and claims data to offer evidence on this distinction and concluded that Part D enrollees overvalue premiums in their plan selection decisions.15 The online Plan Finder offers enrollees the opportunity to look beyond premiums and identify plans with lower overall out-of-pocket costs, to the extent that their drug needs do not change from one year to the next.16 But survey data show that among the small share of beneficiaries who say they themselves have gone online and used the Internet, most have not visited the Plan Finder website (though someone else may have done so for them).17

Relatively large premium increases for a PDP from one year to the next were associated with higher rates of plan switching between 2006 and 2010; but most enrollees with relatively large premium increases did not switch plans in any given year.

Non-LIS Part D enrollees typically see an increase in their plan’s premium if they remain in the same plan from one year to the next. As noted above, 92 percent of PDP enrollees faced higher premiums in 2009 compared to 2008 if they did not switch to a different PDP.18 Most Part D enrollees have PDPs available to them that would charge a lower premium, although the lower-premium PDPs do not always produce lower overall out-of-pocket costs.

PDP enrollees facing a monthly premium increase of $20 or more switched at two to four times the average rate overall. Still, over two-thirds of enrollees in PDPs that raised premiums by at least $20 stayed in that PDP the following year. PDP enrollees who faced especially large monthly premium increases were more likely to change PDPs than those facing lower premium increases (Exhibit 6). For example, 28 percent of PDP enrollees facing a monthly premium increase of at least $20 switched PDPs during the annual enrollment period (averaged across the four enrollment periods between 2006 and 2010). By contrast, only 7 percent of those facing a more modest premium increase (up to $10 or no change in their premium) switched PDPs, while 8 percent of those facing a premium decrease switched PDPs. Still, a significant majority of enrollees stayed with the same PDP regardless of the premium change they were facing in their current plan.

Switching Rates Were Higher Among Non-LIS PDP Enrollees Facing Larger Premium Increases, Compared to Other Enrollees, 2006-2010

Enrollees in PDPs that made changes to their benefit designs, such as increasing deductibles or dropping coverage of brand-name drugs in the gap, were more likely to switch plans than enrollees in PDPs that did not change their benefit design.

Most PDPs retain the same basic benefit design from one year to the next: PDPs with coverage in the gap retain that coverage, those with deductibles continue to use deductibles, and those using cost-sharing tiers continue doing so. But in every year, some plans do make changes to their benefit designs. For example, about one in six PDPs made changes to their deductibles between 2009 and 2010, and a smaller subset of PDPs dropped coverage that they had offered for brand-name drugs in the coverage gap in the years from 2006 to 2008.

Through their plan choices, Part D enrollees who switched plans demonstrated a preference for PDPs with no deductibles or relatively small deductibles. Although most plans tend to make no change in their benefit design from year to year with regard to the deductible, there were more notable changes between 2009 and 2010. In 2009, about 13 percent of PDP enrollees were in plans that were adding or raising the deductible for the 2010 plan year, and another 4 percent were in plans that were lowering or eliminating the deductible. Among PDPs that were increasing the deductible between 2009 and 2010, the weighted average increase in the deductible was $120 (the maximum deductible in 2010 was $310).

PDP enrollees in plans that increased or added a deductible for 2010 were about twice as likely to switch PDPs as those in plans that did not change how deductibles were used or that lowered or eliminated deductibles (Exhibit 7). Furthermore, enrollees in PDPs retaining an existing deductible in 2010 were much more likely to switch to another plan than those in PDPs with no deductible.19 Other evidence supports the idea that beneficiaries tend to overpay (in terms of premiums) for plans without a deductible.20

Switching Rates Were Higher Among Non-LIS PDP Enrollees Facing a Higher Deductible, Compared to Other PDP Enrollees, 2009-2010

Enrollees in plans that dropped coverage of brand-name drugs in the gap in the first two years of the program were more likely to switch plans than enrollees in plans that made no changes to gap coverage, although only a very small share of the PDP population had this generous gap coverage of brand-name drugs, and only a handful of PDPs offered it (Exhibit 8). In 2006 and 2007, most of the small number of PDPs that offered some coverage for brand-name drugs in the coverage gap faced costly adverse selection, whereby the more extensive gap coverage was worth the higher premium only for those who expected to reach the coverage gap. As a result, nearly all of these PDPs elected to modify or drop that coverage (or left the market) for either the 2007 or 2008 plan year.

Switching Rates Were Higher Among Non-LIS PDP Enrollees Who Lost Brand-Name Gap Coverage, Compared to Other Enrollees, 2006-2008

Enrollees whose plans were dropping coverage of brand-name drugs in the gap at the end of 2006 or 2007 switched PDPs at a rate four times greater than the average rate of switching among PDP enrollees. A large share of enrollees in this situation (39 percent in 2006 and 50 percent in 2007) switched out of their plans in those two enrollment cycles, compared to a smaller share (7 percent in 2006 and 11 percent in 2007) of those enrolled in PDPs that made no change in their gap coverage. These counts do not include enrollees forced to pick a new plan because their PDP exited the program entirely. Through the process of adverse selection leading to a “death spiral,” the availability of PDPs with generous gap coverage for brand-name drugs mostly disappeared by 2008.21

DISCUSSION

Our analysis shows that most Part D enrollees did not change their selection of a plan from one year to the next during the annual enrollment period for Medicare prescription drug coverage. Even over a five-year period, most did not change plans outside of special circumstances, such as when a plan sponsor reorganized plan offerings or acquired another company’s plans. The low rate of plan switching in Part D is similar or somewhat higher than those in some other settings, where choice of plans may be more consequential since it involves a full array of health services and may require switching doctors rather than pharmacies. For example, in the Federal Employees Health Benefit Program, about 12 percent of federal employees switched plans annually between 1996 and 2001.22 A similar rate of switching (13 percent) has been reported for all nonelderly Americans with employer-sponsored health insurance, although that rate includes involuntary switching resulting from changes in jobs or in employer plan offerings.23 In some other settings, switching rates have been lower than in Part D. For example, the switching rate in the Massachusetts Commonwealth Care/Health Connector ranged from 2.5 percent to 6.9 percent between 2009 and 2013.24 Although there are no recent published studies of switching in Medicare Advantage, a 1996 survey of Medicare managed care enrollees found that about 7 percent had switched from one Medicare Advantage plan to another in the previous year, and a 2000 survey found that only 4 percent switched Medicare Advantage plans.25

The evidence presented here and in other studies suggests that many Part D enrollees could lower their costs by engaging annually in the process of reviewing and comparing their plan options during the annual enrollment period, and when appropriate, switching to a lower-cost plan.26 The reasons for the low level of switching in Part D are not clear. In one view, enrollment stability could be a sign of enrollees’ satisfaction with their plans. Another view is that beneficiaries avoid “rocking the boat,” by staying in their current plans, preferring the status quo (even at a higher cost) over the unknowns of a new plan.27 Alternatively, the low rate of switching plans could indicate that Medicare beneficiaries are not fully engaged in the Part D program’s choice-based system and that the task of reviewing and comparing plans in the face of many different options may be too difficult or may not seem worth the effort. This view is supported by some qualitative evidence from polls and focus groups, where beneficiaries have reported that they would prefer less choice and a simpler system.28 This view is also supported by behavioral economics research which suggests that decision makers who face a wide range of choices have more difficulty making decisions, make poorer choices, and may in fact fail to make any decision whatsoever.29

Our analysis suggests that higher premiums, higher deductibles, and less generous coverage in the gap are associated with higher than average PDP switching rates, but even with these changes, only a small share of Part D enrollees switched away from PDPs that raised premiums, increased deductibles, or dropped brand gap coverage. Enrollees who switched PDPs were more likely to face lower premiums than those who did not. However, switching plans was much less likely to lead to a reduction in the overall amount that enrollees pay out of pocket for their drugs (excluding premiums). This finding suggests that even those enrollees who undertake the task of reviewing their plan options may not be fully aware of the tools available that would help them compare total costs. For example, if a beneficiary enters their drug regimen into the Plan Finder website developed by CMS, the program will calculate total costs for all plans in the beneficiary’s area and array them in order from least to most costly—simplifying the information the beneficiary needs to review. Some observers have suggested that more availability of one-on-one counseling or more targeted information provided regularly to Part D enrollees could reduce the transaction costs associated with switching plans.30

To the extent that Part D enrollees do not regularly evaluate their plan options or select a new plan even in the face of higher costs, the competitive model inherent to Part D may fall short of expectations. Policymakers may want to consider ways to simplify the required decision making for beneficiaries and provide better decision-support tools. CMS has taken some key steps in the last few years by reducing the number of competing plans and requiring that multiple plan offerings by the same plan sponsor have meaningful differences. CMS has also taken steps since the start of the program to improve the quality of available plan information with enhancements to the online Plan Finder and the availability of better performance measures in the star rating system. Nevertheless, many beneficiaries do not take advantage of these tools on a regular basis, and some are reluctant to initiate research into alternate plan selections because they underestimate the potential savings they could achieve.31 This suggests that more could be done to reduce the number of plan offerings and make it easier for beneficiaries to compare plans, thereby improving the environment for reviewing and selecting plans.32

Our findings have implications beyond Part D, as policymakers debate options for broader Medicare restructuring, including options that would increase the role of private plans in Medicare. The evidence to date from Part D suggests that most beneficiaries, once enrolled, tend to stick with the plans they have chosen, even when they are faced with relatively large premium increases. While this tendency likely reflects a mix of both satisfaction with the status quo and some reluctance to examine alternatives or make a change, it also points to a disconnect between theory and reality in this and potentially other choice-based systems for Medicare. In the face of evidence suggesting that plans will retain most of their enrollees regardless of premium increases or modifications to other plan features, plan sponsors may have less incentive to keep costs down. The result could be higher costs for both beneficiaries and the federal government, because under the structure of Part D, where both the government’s share of the premium and the beneficiary’s premium amount are derived from the average of plan bids, these costs go up as plan bids increase. Results of our study raise questions about the degree to which beneficiaries are willing or able to let cost be their ultimate guide in choosing a plan. As a result, the competitive signal is not sent to plan sponsors, and beneficiaries could miss out on an opportunity to achieve savings.

This issue brief was authored by Jack Hoadley and Laura Summer of Georgetown University; Elizabeth Hargrave of NORC at the University of Chicago; and Juliette Cubanski and Tricia Neuman of the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The authors thank Amanda Tzy-Chyi Yu, Jean-Ezra Yeung, Tianne Wu, and Samuel Stromberg at NORC at the University of Chicago for programming services; Christopher Powers at CMS for assistance in the data acquisition process; Gretchen Jacobson at the Kaiser Family Foundation and Tom Rice at UCLA for additional input and review.