HIV, Intimate Partner Violence, and Women: New Opportunities Under the Affordable Care Act

Introduction

Women in the United States experience high rates of violence and trauma, including physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, and women with HIV, who represent about a quarter of all people living with HIV in the U.S., are disproportionally affected.1,2,3 Intimate partner violence (IPV), also called domestic violence (DV)4, in particular has been shown to be associated with increased risk for HIV among women as well as poorer treatment outcomes for those who are already infected.5,6 In addition, it has been suggested that women are at risk of experiencing violence upon disclosure of their HIV status to partners.7 In recognition of the risks experienced by women with HIV, President Obama issued a Presidential Memorandum in 2012 establishing an interagency working group to examine the intersection of HIV, violence against women and girls, and gender-related health disparities, noting, among other things, that “[g]ender based violence continues to be an underreported, common problem that, if ignored, increases risks for HIV and may prevent women and girls from seeking prevention, treatment, and health services.”8 Given the role that IPV plays in HIV risk, transmission, and care and treatment, finding ways to mitigate its effects is an important part of addressing the HIV epidemic among women in the United States.

| Table 1. Key Terms and Definitions | |

| Term | Definition |

| Violence | Four categories: physical violence, sexual violence, threat of physical or sexual violence, and psychological/emotional abuse.9 |

| Intimate Partner | Intimate partners can include current and former heterosexual or same-sex: spouses (including common-law spouses), non-marital partners, dating partners such as boyfriends/girlfriends, and separated spouses. Partners may or may not be cohabiting and the relationship may or may not involve sexual activities.10 |

| Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) | “Intimate partner violence includes physical violence, sexual violence, threats of physical or sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner.”11 |

| Trauma | Trauma “can refer to a single event, multiple events, or a set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically and emotionally harmful or threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.”12 |

One potential avenue for doing so is the Affordable Care Act (ACA) which, in addition to expanding health coverage to millions of uninsured individuals in the United States, offers new opportunities for addressing the needs of women at risk for and living with HIV who have experienced IPV. This issue brief provides an overview of these new opportunities, as well as a summary of key statistics and definitions. While the focus of this brief is on the experience of IPV and HIV among women, it is important to recognize that men too experience IPV and other forms of violence that put them at increased risk for HIV.13

Key Statistics

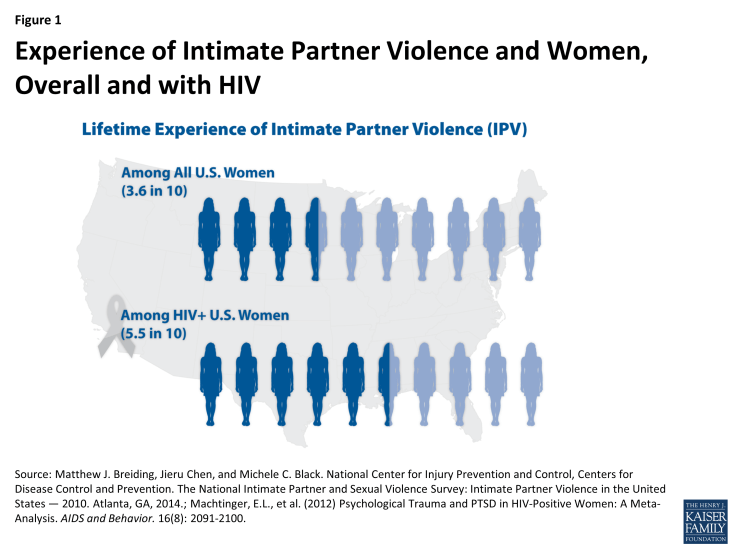

Women in the United States experience high levels of violence, including sexual violence, across their lifetimes, with the most recent data indicating that approximately 27% of US women report ever having experienced unwanted sexual contact.14 Moreover, an estimated 36% of all US women report ever having experienced IPV including rape, physical violence, and/or stalking.15 Among HIV positive women, IPV is even more prevalent, reported by 55% of women living with HIV.16 In addition to the traumatic impact IPV has on all women, the experience of trauma and violence is also associated with poor treatment outcomes and higher transmission risk among HIV positive women.17,18

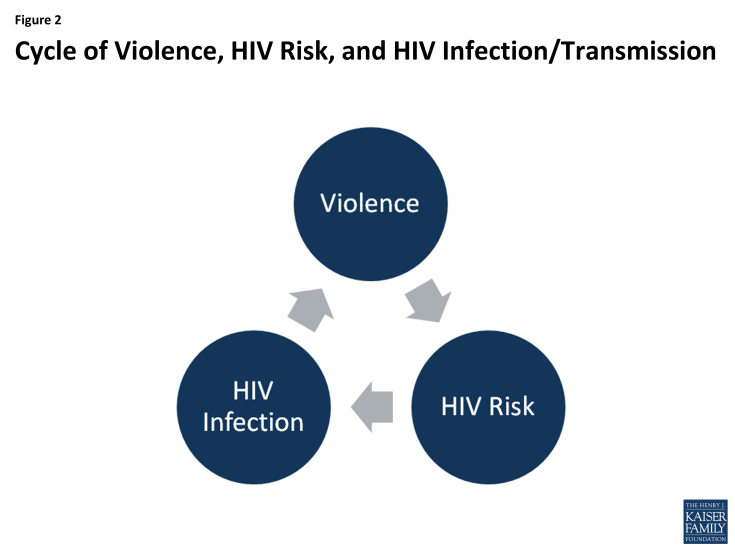

In many cases, the factors that put women at risk for contracting HIV are similar to those that make them vulnerable to experiencing trauma and IPV. Women in violent relationships are at a four times greater risk for contracting STIs, including HIV, than women in non-violent relationships and women who experience IPV are more likely to report risk factors for HIV.19 A nationally representative study found 20% of HIV positive women had experienced violence by a partner or someone important to them since their diagnosis and that of these, half perceive that violence to be directly related to their HIV serostatus.20 Indeed, these experiences are interrelated and can become a cycle of violence, HIV risk, and HIV infection. In this cycle, women who experience IPV are at increased susceptibility for contracting HIV and HIV positive women are at greater risk for becoming victims of IPV.21,22

How The ACA Addresses Intimate Partner Violence

The ACA, signed into law in 2010, aims to expand access to affordable health coverage and reduce the number of uninsured Americans through the creation of new health insurance marketplaces in each state and by expanding Medicaid, in states that choose to expand their programs, as well as through other reforms. Beyond these broad changes, there are several provisions that are specifically designed to protect individuals who have experienced IPV, including those with HIV. These include explicit protections in the law, as well as regulatory interpretation and guidance, as follows:

- The elimination of pre-existing condition exclusions and premium rate setting based on health status, such as HIV, and other factors, including whether someone is a survivor of IPV. Prior to the ACA, health insurance companies were able to deny insurance coverage or charge individuals different rates based on a range of factors including whether someone was a survivor of IPV; in fact, seven states specifically allowed insurers to deny coverage to survivors and fewer than half of states (22) had enacted comprehensive IPV related anti-discrimination insurance protections.23 Under the ACA, issuers are no longer permitted to deny an individual coverage or charge higher rates based on past or current experience of IPV or gender. Rates are permitted to vary by only age, geographic location, and smoking status. This provision is important for HIV positive domestic violence survivors who in the past could have faced denials or higher rates based on that experience, their gender, or their HIV status.

- A range of no-cost preventive services for women including screening and counseling for IPV. Screening and counseling for IPV is now a preventive service under the ACA that must be covered without cost-sharing. Most private health plans and all Medicaid expansion programs, in states that expand, must provide such services free of charge. However, there is no requirement that traditional state Medicaid programs provide no-cost IPV screenings as part of the state benefit package. Screening might occur during a routine office visit or well-woman exam and might entail a provider asking a patient about their current and past relationships. The Department of Health and Human Services’ Office on Women’s Health states that if IPV/DV is disclosed, counseling can consist of a brief session that 1) addresses a patient’s immediate safety; 2) discusses the connection between IPV/DV and other health concerns; and 3) provides linkage to support services and resources.24

- Exemption from the individual mandate due to recent experience of IPV. Beginning in 2014, the ACA required most individuals to carry comprehensive health coverage, also known as “minimum essential coverage” or the “individual mandate.” Those without coverage must either qualify for an exemption or pay a tax penalty. One exemption category is for individuals who have recently experienced domestic violence. No additional supporting documentation needs to be provided to qualify, though the applicant is asked to explain how “the hardship,” in this case experience of domestic violence, prevented them from gaining coverage. This exemption recognizes that those who have recently experienced domestic violence may lack financial security, stable housing, or be dealing with other complicated life situations that make obtaining insurance coverage difficult.

- Allowance for married survivors of IPV to file taxes separately from their spouse and claim a premium tax credit. To help make insurance coverage more affordable, the ACA provides advanced premium tax credits to individuals between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level who purchase private insurance through state and federal exchanges. Per the ACA, a married individual needs to file taxes jointly with their spouse to be eligible for premium tax credits which can help make health insurance coverage purchased through a marketplace more affordable. The Department of Treasury and Internal Revenue Service (IRS) issued guidance and subsequent regulations in April and July of 2014 that permit a survivor of IPV living apart from their spouse at the time of tax filing and unable to file a joint return, to claim a premium tax credit while using a married filing separately tax status for up to three consecutive years.25 Allowing DV survivors to file using this tax status and still obtain premium tax credits is designed to protect them from having to interact with an abuser at tax time while still being able to access insurance subsidies.

- Special Enrollment Period for survivors of IPV. While enrollment in private health plans through the insurance marketplaces must occur during a specific open enrollment period in most cases, there are exceptions. Individuals experiencing certain qualifying events, such as a marriage, divorce, or birth of a child, may be granted a Special Enrollment Period (SEP) and permitted to enroll outside of the specified open enrollment window. At the close of the first open enrollment period in 2014, in light of the Treasury Department and IRS guidance and regulations (explained above), a special enrollment period (SEP) was extended to victims of IPV in federally facilitated marketplaces and state-run marketplaces were allowed to do the same.26 In this case, the SEP allowed those eligible an additional opportunity to access coverage with tax credits as described above. The SEP lasted through May 30, 2014, a two month extension of the original open enrollment deadline.

- Most individual and small group plans and all Medicaid expansion plans now cover mental health and substance use services as one of ten “essential health benefit” categories. The ACA requires that individual and small group plans, sold both inside and outside the health insurance marketplaces, as well as Medicaid expansion plans, provide ten categories of essential health benefits including among others: ambulatory services; hospitalization; prescription drugs; and of note in this instance, mental health and substance use disorder services. Prior to this requirement, it was estimated that about one-third of those enrolled in individual market products lacked coverage for substance use services and about 20 percent were without coverage for mental health services.27 In addition, the ACA applies Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 standards to the individual and small group insurance markets which means that these services must now be covered at parity with medical and surgical benefits. Numerous studies have observed an association between IPV and an array of mental health conditions, including Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety, among others.28,29 Additionally, people with HIV experience mental health and substance abuse comorbidities at higher rates than the population overall.30,31,32 Access to mental health and substance use services, therefore, is an important component of comprehensive health coverage for many people living with HIV and perhaps especially for those dealing with current or past IPV and trauma.

- Maternal and child home visitation program includes focus on domestic violence. The ACA funded the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting initiative, a competitive grant program that provides states with resources to respond to the needs of children and families in at risk communities and includes specific opportunities to address domestic violence. Seeking to improve, coordinate, and provide home visitation services, the statute required states to conduct a statewide needs assessment for FY11 including identification of communities with concentrations of domestic violence. Participating states are required to demonstrate a reduction in crime or domestic violence, among other benchmarks which were also identified as target outcomes for participating families. A 2013 study of 260 HIV positive women with a mean age of 46, found that 86% of those surveyed were mothers and 31% had children living at home.33 Given that a large share of women with HIV are likely to be parents and that women with HIV are disproportionately affected by IPV, home visits that include opportunities to address domestic violence could be particularly important for this population.

- Competitive grant program to support pregnant teens and women, including those experiencing domestic and sexual violence, established under the Pregnancy Assistance Fund. The ACA also established a competitive grant program for states to support pregnant and parenting teens and women, allowing states to use funds to provide intervention and support services to pregnant women who are victims of domestic, sexual violence or stalking. The fund is also available to support the provision of assistance and training related to these issues for federal, state, local and other partners.

- The National Prevention Strategy includes Injury and Violence Free Living as a priority area. Finally, the ACA established the National Prevention Council and called for the development of the National Prevention Strategy. With an aim of realizing the benefits of prevention in healthcare, the strategy includes seven national priority areas including Injury and Violence Free Living.34 In framing this this priority area, the strategy makes specific references to intimate partner violence, including the recommendation that the federal government “research and disseminate effective methods to prevent intimate partner violence and sexual violence.”

As mentioned above, in addition to the changes brought on by the ACA, and recognizing the complexity of these issues, in March 2012, President Obama issued a Presidential Memorandum establishing an interagency working group on the intersection of HIV/AIDS, violence against women and girls, and gender-related health disparities.35 The memorandum identifies the need to address violence against women within the Nation’s approach to the domestic HIV epidemic. It required the working group to provide recommended relevant updates to the National HIV/AIDS Strategy to the administration as well as to effectively take on a monitoring role to coordinate efforts to address HIV and violence against women and girls across federal agencies. Two reports have been issued by the working group thus far.36

Looking Ahead

Addressing trauma and violence experienced by both HIV positive and negative women aims to provide critical care and support to women in the immediate term, but in the longer term, may also be an important contribution in combating the domestic HIV epidemic. The ACA provisions outlined above provide important opportunities for targeted interventions to address IPV in HIV positive and at risk women, although several challenges remain.

With respect to screening and counseling for IPV, as with all preventive services, coverage does not necessarily equate with uptake by consumers or with the service being offered by providers. Inclusion of DV screening as a reimbursable service and the associated federal and advisory body recommendations may drive up some provision of the intervention but additional efforts may be necessary to generate more widespread provider led IPV screenings. One recent study found that just 23% of women ages 15 to 44 have discussed dating or domestic violence with a provider in the past three years, demonstrating that these screenings are still relatively rare.37(See CDC compilation of IPV screening tools: http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/pub-res/images/ipvandsvscreening.pdf.) In addition, it is important to consider how to maintain confidentiality for women seeking violence-related care, particularly since more women will be covered by private insurance plans that typically send an Explanation of Benefits (EOB) that documents provided services to the principal policy holder, such as a spouse. There also remains the need to raise awareness among providers and women at risk for and living with HIV about the interrelatedness between HIV and intimate partner violence.

Finally, as states make different decisions about ACA implementation, coverage opportunities for enrollees vary across the nation. For example, whether states with state based marketplaces decided to implement the SEP for victims of IPV discussed above is one example. More generally, whether a state decides to expand its Medicaid program to all those below 138% of the Federal Poverty Level (currently 28 states are expanding while 23 are not), as permitted under the ACA, has significant implications for access to coverage for low income individuals. Given that multiple studies have demonstrated that incidence of HIV and IPV both trend with poverty, access to Medicaid expansion, including the associated IPV screening, could play a particularly important role for these populations.38 In addition, access to services, varies by coverage and as noted, IPV screening is not a required covered service for those in traditional Medicaid.

While certain implementation challenges exist, the ACA protections discussed above could present significant opportunities to address IPV, for both women living with HIV as well as those at risk.