Ebola in West Africa: Four Questions for the U.S. Response Going Forward

As of August 14, 2014, the Ebola virus has infected an estimated 1,975 individuals across four countries in West Africa, leading to 1,069 deaths (including three Americans). The official reported numbers, frightening as they are, likely vastly underestimate the true magnitude of the outbreak. Ebola has severely impacted the daily life of affected communities, and raised concerns across the globe about its ongoing spread. The fact that this outbreak has led to so many cases and deaths (approximately 45% of all cases of Ebola ever reported have come since March of this year) is concerning for the individuals and families struggling with the disease, and leads to questions regarding the global capacity to detect and respond to such events. It also brings up four key policy questions for the U.S. concerning its engagement with the international community’s efforts to combat Ebola and other emerging infectious disease outbreaks.

HAS THE U.S. RESPONSE MATCHED THE NEED?

The U.S. government has incrementally ratcheted up its assistance to address the growing Ebola outbreak. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) initially gave $2.1 million in emergency support to multilateral agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) for their response to Ebola in the region, and a limited number of experts from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Department of Defense (DoD), and other U.S. agencies were in the region providing technical assistance and support. As case numbers continued to climb, the disease spread to additional countries, and the three Americans were diagnosed with Ebola, USAID announced the deployment of a Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) and the release of an additional $12.45 million in emergency support for the public health response in the region. The State Department issued a travel warning and ordered the departure of family members of its mission staff in Liberia while the CDC announced on August 7 its intention to provide 50 infectious disease experts within 30 days to assist in the response and issued its own travel warnings for the region. U.S. personnel and resources are meant to join and bolster the broader national and international responses focused on the disease.

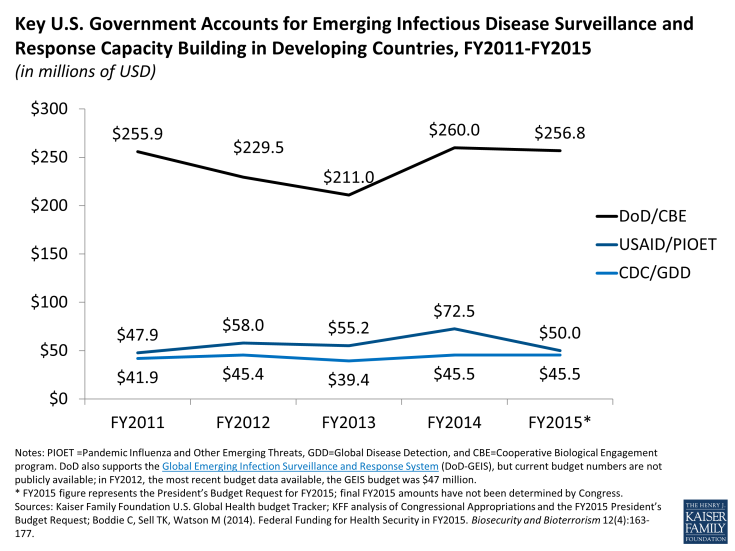

The emergency funding made available for this particular outbreak is in addition to ongoing U.S. support for global emerging infectious disease preparedness and response. Key bilateral USG funding mechanisms for this work include (but are not limited to) the CDC’s Global Disease Detection (GDD) efforts, USAID’s Pandemic Influenza and Other Emerging Threats (PIOET) efforts, and Department of Defense’s Cooperative Biological Engagement (CBE) program (see chart).1

Key U.S. Government Accounts for Emerging Infectious Disease Surveillance and Response Capacity Building in Developing Countries, FY2011-FY2015

Whether or not the U.S. response has matched the need is a complex question. As the chart indicates, however, U.S. funding for these programs has remained mostly stable over the last 5 years. The White House, HHS, CDC, USAID, DoD and other agencies, noting the need for greater attention and investment in such programs, did announce in February 2014 the launch of a new “Global Health Security Agenda” meant to catalyze further action by U.S. government and its partners on emerging diseases and global health security. While no additional funding for this effort has been made available yet, the President’s FY2015 budget request does include an additional $45 million to support CDC’s work on the agenda.

In addition, none of the funding had focused on West Africa prior to this Ebola outbreak. USAID/PIOET has focused on central and eastern Africa, along with South America and South and Southeast Asia, while the DoD/CBE program has been primarily focused on former Soviet states along with parts of Asia and central/Eastern Africa. The CDC maintains or is in the process of setting up 10 GDD centers around the globe, though none are in West Africa (the nearest GDD centers are in Egypt and Kenya). This shows the limitations of the current levels of funding and also the inherent difficulty of trying to predict where the next important infectious disease epidemic might spring up, because such outbreaks are by their nature unpredictable. In another recent example, the 2009 H1N1 outbreak emerged from Mexico, not Asia as had been presupposed by epidemiologists and where the global influenza surveillance effort had been primarily focused.

Despite U.S. contributions and a growing international response to the Ebola outbreak, the needs are still great in the region, with health workers and basic supplies still lacking in many areas. Sierra Leone reports receiving just $7 million of the $25 million it says it needs for Ebola response while Liberia has received $6 million of the $21 million it needs.

HOW DOES THE EBOLA RESPONSE FIT INTO THE BROADER U.S. GLOBAL HEALTH EFFORT?

The U.S. provides ongoing funding for global health programs in all of the Ebola-affected countries, including (depending on the country) HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, maternal and child health, family planning/reproductive health, and water programs (see Table 1). The $14.55 million made available to combat Ebola this year is equal to just a small proportion (2 percent) of the $625.97 million Nigeria received in U.S. global health assistance in FY2013, though it also represents a funding level almost thirty times as large as U.S. global health assistance to Sierra Leone.

| Table 1. U.S. Global Health Assistance to Ebola-Affected Countries, FY2013 Total and by Program Area | |||||||

| Country | Total U.S. Global Health Assistance | Bilateral HIV | TB | Malaria | MCH | FPRH | Water |

| Guinea | $17,880,000 | – | – | $12,371,000 | $2,502,000 | $3,007,000 | – |

| Liberia | $46,932,000 | $3,500,000 | – | $12,370,000 | $11,038,000 | $7,004,000 | $13,020,000 |

| Sierra Leone | $500,000 | $500,000 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nigeria | $625,974,000 | $455,746,000 | $13,008,000 | $73,272,000 | $45,675,000 | $33,496,000 | $4,777,000 |

| Data source: www.foreignassistance.gov | |||||||

An oft-debated question in global health policy has been: do global health programs that focus on specific diseases or conditions contribute – should they contribute – to building general health capacity and community resilience? The circumstances of the Ebola outbreak underscore the links between poor public health capacity and the ability to address specific diseases. After all, any global health or development program is likely to be affected when health workers are becoming infected and dying at an alarming rate, clinics and hospitals are being inundated with patients or shut down, medical staff are not reporting to work or striking for better working conditions, and restrictions on travel and border crossings are in effect. In this case, there is already significant concern about the effects of Ebola on the ability of these countries to address other diseases.

HOW TO STRIKE THE RIGHT BALANCE BETWEEN ACCESS AND REGULATORY SAFETY?

The two candidate Ebola treatments far enough along in the process for use in humans were funded by the DoD, and the National Institutes of Health and Biomedical Advanced Research Development Authority (both within the Department of Health and Human Services), along with the Canadian government, primarily for purposes of developing countermeasures to potential bioterrorism incidents involving the Ebola virus. Though none of the treatments has yet been clinically tested on humans, one of the drugs, ZMapp, has been administered to three people this month (two Americans and a Spanish citizen), and is expected to be provided to several Liberian Ebola patients soon. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), responsible for regulating the development and use of such treatments has taken the unusual step of making an Expanded Access (“compassionate use”) exemption for Ebola treatment, making it available despite the lack of human testing. These actions have sparked debates about innovation, research, development, and access to medicines for neglected diseases such as Ebola, the use of drugs or vaccines prior to regulatory approval, the merits of fast-tracking approval of treatments, and the ethics of first access to limited quantities of life-saving drugs or vaccines. A World Health Organization-convened panel to examine these questions for the current Ebola outbreak recently concluded that, provided certain conditions are met, it is ethical to offer unproven interventions. While these recent debates revolve around the circumstances of this particular Ebola outbreak, they have implications for global health more generally.

CAN THE U.S. HELP COUNTRIES GET AHEAD OF THE CURRENT OUTBREAK OR WILL THIS REMAIN A CATCH UP GAME?

The international response so far has not been able to meet the needs of the countries facing this Ebola outbreak. By many accounts, there remains a serious lack of basic supplies, protective gear, and laboratory capacity, and an insufficient number of health workers to put into place all of pieces of the response that will be necessary to contain this outbreak. There remains an urgent need to fill these gaps, that the U.S., along with other countries and multilateral organizations, can help address with continuing and expanded support as needed. Given the attention to this topic, as Congress and the Administration consider what comes after addressing the immediate needs in West Africa they face a uniquely powerful and opportune moment to focus on the key questions and debates that have been raised by the outbreak and response.

Endnotes

- The DoD also supports the Global Emerging Infection Surveillance and Response System (DoD-GEIS), but current budget numbers are not publicly available. In FY2012, the most recent budget year available, the GEIS budget was $47 million.