The Uninsured Population in Texas: Understanding Coverage Needs and the Potential Impact of the Affordable Care Act

Katherine Young and Rachel Garfield

Published:

Executive Summary

Introduction

In January 2014, the major coverage provisions of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) went into full effect. While millions have gained coverage under the law, many remain outside its reach. In Texas, which had the highest uninsured rate in the nation prior to the ACA and has opted not to expand its Medicaid program, many uninsured residents remain. Much attention has recently focused on the population that is newly-enrolled in coverage, but a focus on the uninsured population, their needs, and the consequences they face because they lack coverage can also inform ongoing policy development in the state. This report uses findings from the 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA to explore who the uninsured in Texas are and to understand their ongoing health care and health coverage needs.

Key Findings

Characteristics of Uninsured Adults in Texas

While the population without health insurance coverage in Texas includes people from a range of backgrounds, most uninsured Texan adults are low-income workers: nearly 70% of uninsured adults are in a working family, and 40% live below the poverty level. Uninsured adults in the state are also, on average, younger and more likely to be people of color than those who have insurance. In addition, 20% of uninsured adults in Texas are undocumented immigrants, who remain outside the reach of many provisions of the ACA.

Patterns of Coverage Among Adults in Texas

While some people lack health insurance coverage during short periods of unemployment or job transitions, for most uninsured adults in Texas, lack of coverage is a chronic problem. Over half of uninsured adults in the state (53%) reported being uninsured for five years or more, including 31% of the uninsured who reported that they have never had coverage in their lifetime. In addition, many Texans experience spells of uninsurance throughout the year, and coverage among those with insurance may not be stable. Among Texan adults who were insured at the time of the survey, 8% reported being uninsured at some point in the past year, and 11% had coverage for the full year but had a change in their coverage source.

Access to Coverage Among Uninsured Adults in Texas

Many uninsured adults in Texas report trying to obtain insurance coverage in the past, but most did not have access to affordable coverage. Most (84%) uninsured adults in Texas report that they do not have access to employer-sponsored coverage through either their job or a spouse’s job. Of the 16% who do have access to coverage through an employer, the majority report that the coverage offered to them is not affordable. In addition, uninsured adults report problems accessing Medicaid, which is not surprising given the limited eligibility for this group in Texas. More than one fifth (21%) of uninsured adults said they tried to sign up for Medicaid in the past 5 years, but the vast majority were told they were ineligible. Some who applied for Medicaid also reported challenges with the application process, with 57% who applied to Medicaid (including those who enrolled) indicating that some part of the process—was somewhat or very difficult. Last, uninsured Texans report problems in finding affordable coverage on their own: prior to the ACA, 15% tried to purchase a plan directly from an insurer, but most said that the policy offered to them was too expensive.

Access to Health Care Services Among Uninsured Adults in Texas

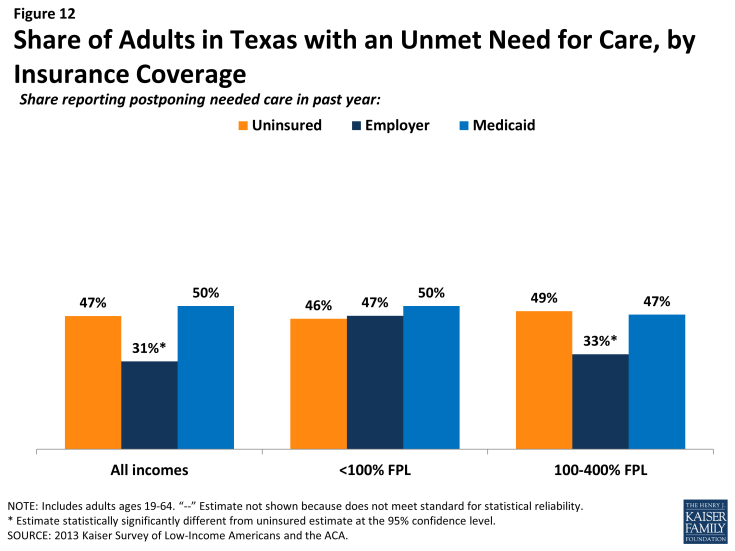

A large segment of uninsured adults in Texas have little or no connection to the health care system.Only 48% of uninsured adults report that they have a usual source of care, or a place to go when they are sick or need advice about their health, and only 28% of uninsured adults say they have a regular doctor at a usual source of care, less than half of the rate of insured adults in Texas. This lack of a connection to the health care system leads many uninsured adults to go without care. Fifty-six percent of uninsured adults in Texas reported at least one health care visits in the past year, compared to 89% of Medicaid beneficiaries and 85% of adults with employer coverage. Still, many uninsured Texans have health needs.Uninsured adults are less likely than those with employer coverage to report receiving care for an ongoing health condition. About half (47%) of the uninsured and half (50%) of Medicaid beneficiaries in Texas report needing but postponing care, compared to 31% of adults with employer coverage. The most common reason for postponing care among the uninsured is cost.

Financial Security Among Uninsured Adults in Texas

Health care costs pose a challenge for poor and moderate-income families in Texas, particularly if they are uninsured. Health care costs translate to medical debt for many poor adults. Over a third (36%) of uninsured adults in Texas have outstanding medical bills. These medical bills can cause serious financial strain. In addition, the vast majority of uninsured Texas adults across all income groups reported that they lack confidence in their ability to afford health care, given their current finances and health insurance situation. Difficulty or worry about paying for health care translates to expenses in other areas as well, and almost six in ten uninsured adults below poverty (59%) reported that they feel generally financially insecure. This general financial insecurity translates to concrete financial difficulties in making ends meet. Patterns across coverage groups indicate that this issue is common among people in poverty, regardless of insurance.

Policy Implications

The survey shows that affordability and access are major challenges to obtaining coverage for adults in Texas. Though most uninsured adults or their spouses work, most still live on very limited means and are unlikely to be able to afford coverage on their own.

For those who are eligible for coverage, the ACA can help facilitate access to affordable coverage by requiring employers to offer coverage, making available tax credits for Marketplace coverage, and prohibiting denials of coverage. These provisions could address barriers that Texans have faced in accessing private coverage, such as not having coverage through a job, not being able to afford coverage, or having a health condition that might price them out of the market. Further, provisions to simplify Medicaid application and enrollment may lead to smoother enrollment and renewal in the Medicaid program.

Open enrollment has ended for Marketplace coverage in 2014, but as of November, people can sign up for Marketplace plans to begin in 2015. In addition, the survey findings reveal that many Texans lose and gain coverage throughout the year because of job changes, income fluctuations, or problems at renewal. Thus, enrollment is an ongoing process, and ongoing efforts to enroll and keep people in coverage will influence the number of people who gain coverage. A substantial share of the uninsured population has been outside the insurance system for quite some time and may require targeted outreach and education efforts to link them to the health care system and help them navigate health insurance should they gain coverage.

However, because Texas is not expanding Medicaid, over a million uninsured Texans who would have been eligible for Medicaid under the ACA instead fall into the coverage gap. They are not eligible for the Marketplace subsidies and tax credits, most do not have access to coverage through a job, and they likely are unable to afford coverage on their own. These remaining uninsured adults are likely to continue to face access barriers and financial hardship due to health care costs. These individuals will continue to have health care needs and may continue to lack a usual source of care, forego preventive care, and face cost barriers to using services. As attention shifts to the newly-insured population, the uninsured in the state will still need care, and clinics and health centers will continue to help serve the poor and moderate-income population.

Report

Introduction

Background

Lack of insurance coverage has been a longstanding policy challenge both nationwide and especially in Texas. Prior to the ACA, the uninsured rate in Texas was 27%, the highest in the nation and well above the national rate of 18%.2 This high uninsured rate reflects limited availability of both private and public coverage. Private coverage is closely tied to employment, but not all workers are offered affordable coverage through their jobs. In particular, people who work in certain industries (such as service or agriculture), who work part-time, or who earn low wages are less likely to be offered coverage than other workers.3 Private coverage purchased directly from insurers (nongroup coverage) was not guaranteed in Texas prior to the ACA, and insurance companies could charge higher premiums for sicker or older individuals, making coverage unaffordable for many uninsured adults.4 Last, Medicaid eligibility in the state has historically been very limited for adults. While children in the state may be eligible for Medicaid or CHIP if their family income is below 206% of poverty (about $40,800 for a family of three in 2014), parents must have income below 20% of poverty, or about $3,900 a year for a family of three, to qualify for coverage. Further, adults without dependent children and undocumented immigrants are ineligible for Medicaid in Texas, regardless of their income.5

To address the challenge of the uninsured, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) includes an expansion of Medicaid and the creation of new Health Insurance Marketplaces. With the Supreme Court ruling in June 2012, the Medicaid expansion essentially became optional for states, and as of June 2014, Texas had opted not to expand its Medicaid program. This decision has created a “coverage gap” among low-income adults. Under the ACA, people with incomes between 100% and 400% of poverty may be eligible for premium tax credits when they purchase coverage in a Marketplace. Because the ACA envisioned low-income people receiving coverage through Medicaid, people below poverty are not eligible for Marketplace subsidies. Thus, some poor adults in Texas will fall into a “coverage gap” of earning too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to qualify for premium tax credits. People in the coverage gap, all of whom have incomes below 100% of poverty, are ineligible for financial assistance under the ACA, while people with higher incomes will be eligible for tax credits to purchase coverage.

While the state is not expanding Medicaid eligibility under the ACA, there are some ACA-related changes to the state’s Medicaid program. Changes to the Medicaid enrollment process occurred in 2014, regardless of expansion decisions. Texas must make Medicaid determinations based on new modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) eligibility levels. The ACA also established a streamlined enrollment process for all states that allows people to use one single application for Marketplace or Medicaid coverage. Individuals are able to apply for coverage through HealthCare.gov, the state Medicaid/CHIP website, in person, on the phone, or through the mail. In addition, Medicaid eligibility determinations will now use verification based on existing data sources such as Social Security Administration data, rather than requiring families to provide paper documentation.6

Characteristics of Uninsured Adults in Texas

While the population without health insurance coverage in Texas includes people from a range of backgrounds, most uninsured Texan adults are low-income workers. Uninsured adults in the state are also, on average, younger and more likely to be people of color than those who have insurance. In addition, while most uninsured adults are citizens or legal immigrants, a notable share of uninsured adults in Texas are undocumented immigrants, who remain outside the reach of many provisions of the ACA.

Most uninsured adults are in low-income working families.

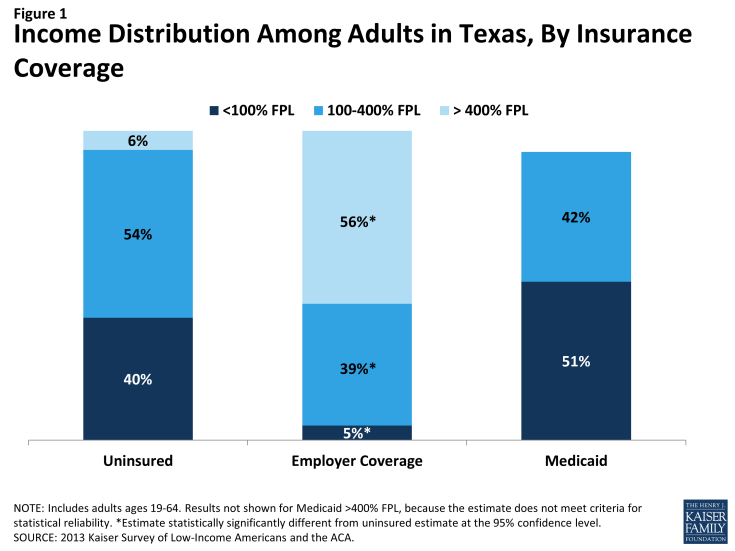

Uninsured adults in Texas are more likely than other residents to be low-income. For example, 40% of uninsured adults are poor (that is, living below the poverty level) in contrast to 5% of adults with employer coverage (Figure 1 and Appendix Table A1). People living below the poverty level live on limited resources: In 2014, the poverty level for a family of three is less than $20,000 a year.1 In Texas, most poor uninsured adults are ineligible for coverage expansions under the ACA. Adults with Medicaid are the most likely of any coverage group to be poor, reflecting the fact that adult income eligibility is limited to those with very low incomes.2

About half of uninsured adults in Texas have family incomes between 100 and 400% of poverty (Figure 1), the income range for premium tax credits for Marketplace coverage. Some of these people may be not be able to obtain tax credits due to their immigration status or because they have an offer coverage from an employer. However, most are potentially eligible for financial assistance in purchasing coverage.

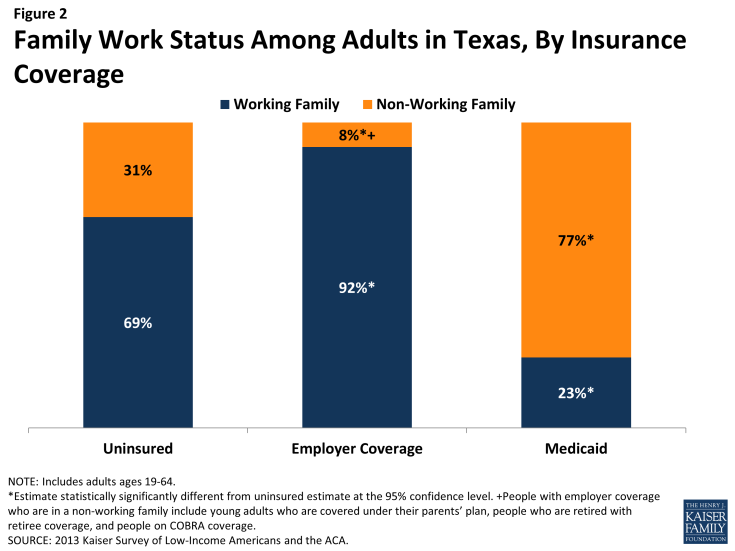

Though they are primarily low-income, most uninsured Texans are in a working family. Nearly seven in ten (69%) uninsured Texan adults live in families where they or their spouse are working either full or part-time (Figure 2). These workers may be employed by someone else or may be self-employed. Few adults who meet the limited income levels for Medicaid eligibility in the state are in a working family (23%), as even limited earnings are likely to make adults ineligible. However, not surprisingly, most adults with employer coverage are in a working family, which is the main pathway to their coverage.

The data on the income and work status of uninsured Texas adults indicates that the challenge of extending coverage may be linked more to affordability and access than to lack of jobs. Though most uninsured adults or their spouses work, most still live on very limited means and are unlikely to be able to afford coverage on their own.

Demographic characteristics of uninsured adults could inform outreach efforts.

Uninsured adults in Texas also differ from insured adults with regards to demographic characteristics, often reflecting an association with income or work status. For example, uninsured adults are likely to be younger than insured adults, as younger adults have lower incomes and looser ties to employment than older adults. Nearly seven in ten (69%) uninsured adults in Texas are ages 19-44 compared to 55% of adults with employer coverage and 44% with Medicaid (Appendix Table A1). There also are significant racial and ethnic differences in health coverage among nonelderly adults in the state, primarily reflecting differences in income by race/ethnicity. For example, uninsured adults are more likely to be Hispanic (56%) than adults with employer coverage (24%).

Most (62%) uninsured adults in Texas are U.S. citizens. Of those who are not citizens, however, many are undocumented immigrants. The survey estimates that undocumented immigrants make up 20% of the uninsured adult Texas population.3 Under federal law, undocumented immigrants are not eligible for Medicaid. As a result, even if Texas were to expand the Medicaid program, a sizeable number of Texas residents would remain uninsured. Further, many Texas families include both documented and undocumented immigrants, and these families often see government-run programs through the prism of protecting immigration status information about their family members.

Understanding the demographic characteristics of the remaining uninsured population in Texas can inform efforts to reach, educate, and enroll individuals into health coverage under the ACA and to continue to serve the uninsured in the state. Information on how to navigate the health care system can be tailored to specific age groups or ethnic groups to reach them more effectively. Conveying how the ACA does or does not tie into immigration may be important for outreach and communication with the immigrant community.

Patterns of Coverage Among Adults in Texas

Health insurance coverage is dynamic, and every year thousands of Texans gain, lose, or change it. However, for most uninsured adults in Texas, lack of coverage is a long-term issue that spans many years. In addition, many insured Texans face unstable coverage that puts them at risk for becoming uninsured.

For most uninsured adults in Texas, lack of coverage is a long-term issue.

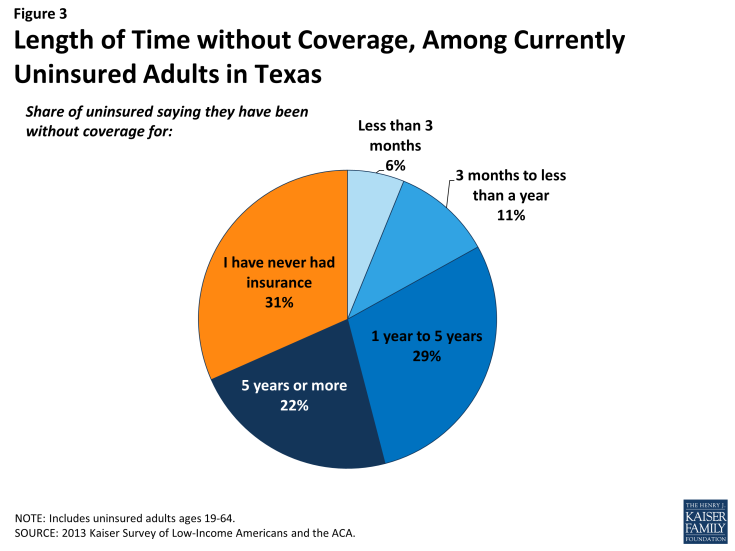

While some people lack health insurance coverage during short periods of unemployment or job transitions, for many uninsured adults in Texas, lack of coverage is a chronic problem. Over half of uninsured adults in the state (53%) reported being uninsured for five years or more, including 31% of the uninsured who reported that they have never had coverage in their lifetime (Figure 3). Of note, over 4 in 10 (44%) poor uninsured adults (<100% FPL) reported never having coverage in their lifetime, and over 6 in 10 poor uninsured adults have been uninsured for at least five years. These adults will likely remain uninsured without a Medicaid expansion (see Appendix Table A2). A smaller share of moderate-income (100-400% FPL) uninsured Texan adults are long-term uninsured, but at 24%, a sizeable share of the latter still has never had health insurance.

The data on length of time uninsured indicate that many uninsured adults in the state are likely to remain uninsured for extended periods without a substantial change in the availability of coverage. While some may move into coverage after a brief period of uninsurance, most are likely to remain uninsured. In addition, the uninsured in Texas have varying levels of experience with the insurance system. While some previously had coverage, a substantial share has been outside the insurance system for quite some time. The long-term uninsured may require targeted outreach and education efforts to link them to the health care system and help them navigate health insurance should they gain coverage.

Many Texans will experience spells of uninsurance throughout the year, and coverage among those with insurance may not be stable.

For most insured adults in Texas, coverage is continuous throughout the year and over time. However, when accounting for both insured people with a gap in their coverage and uninsured people who had only recently lost coverage, the survey indicates that sizeable shares of adults in Texas lose or gain coverage over the course of a year. Among Texan adults who were insured at the time of the survey, 8% reported being uninsured at some point in the past year (see Table 1), and those who had a gap in coverage were uninsured for close to half a year (5.7 months) on average (data not shown).

Even for those who have coverage throughout the entire year, coverage may not be stable. Among adults with insurance coverage, 11% had coverage for the entire year but reported that they had a change in their coverage (Table 1). Coverage changes may be due to a number of different factors including changes in employment, changes in eligibility for public programs, or simply a change in plan or insurance carrier. The most common reasons for a change in coverage appear to be related to changes in employment or changes in plans during open enrollment, as most Texans with a coverage change reported changing from an employer plan to another employer plan.

| Table 1: Coverage Dynamics Among Insured Adults in Texas, by Income and Current Coverage | ||||||||

| All | By Income | By Current Coverage | ||||||

| % | <100% FPL% | 100-400% FPL% | >400% FPL% | Employer% | Medicaid% | |||

| Insured Adults | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| Gap in Coverage in Past Year | 8% | — | 14% | — | 7% | — | ||

| Changed Coverage During Year | 11% | — | 8% | 15% | 14% | — | ||

| Same Coverage for Full Year | 80% | 78% | 78% | 83% | 79% | 80% | ||

| NOTES: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown. “–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or sample size too small for analysis are not provided. SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. |

||||||||

In addition, a small number of insured adults in Texas (5%) reported challenges in either renewing or keeping their coverage, another indication of instability in coverage throughout the year (data not shown). In regards to Medicaid, eligibility is closely tied to income, and adults’ income may fluctuate throughout the year; adults must report changes in income that may affect their eligibility throughout the year, and poor and moderate-income people are very likely to have part-time or seasonal work that leads to income fluctuations over the course of a year. In addition, adults must renew their Medicaid coverage either in person, by phone, or online annually.

The survey findings on changes in insurance coverage during the year have implications for ongoing ACA implementation in the state. Though open enrollment is over, people may still enroll in Marketplace coverage during “special enrollment periods,” such as loss of job-based coverage, marriage, birth of a child, or another change in family circumstance.1 Further, while Medicaid eligibility is limited, as adults’ income fluctuates, they may gain Medicaid eligibility, and people who are eligible can gain coverage at any point during the year. Survey findings demonstrate that people frequently move around within the insurance system throughout the year, and many are likely to find themselves in a situation where they could gain ACA coverage. Conversely, people may lose coverage—either due to loss of a job or changes income that lead to loss of Medicaid— and find that they fall into the coverage gap.

Access to Coverage Among Uninsured Adults in Texas

Many uninsured adults in Texas report trying to obtain insurance coverage in the past, but most did not have access to affordable coverage. Prior to the ACA, options for coverage—particularly for the poor or moderate-income—were very limited. For most poor adults in the state, coverage options continue to be limited under the ACA.

Very few uninsured Texans have access to affordable coverage through an employer.

The vast majority of uninsured adults in Texas do not have access to employer coverage. More than eight in ten (84%) uninsured adults in Texas report no access to employer coverage, either because no one in their family is working for an employer, their or their spouse’s employer does not offer coverage, or they are ineligible for that coverage (Table 2). For example, 41% of uninsured adults in Texas are in a family without an employer, meaning both they and their spouse (if married) are either not working or are working but are self-employed. Over a third (38%) of uninsured adults are in a family that has an employer who does not offer coverage to any workers, and one in twenty (5%) are in a family that works for an employer who offers coverage but they are ineligible for that coverage. Most are ineligible because they work part-time or are in a waiting period.

| Table 2: Access to Employer Health Coverage Among Uninsured Adults in Texas | ||||

| All | By Income | |||

| <100% FPL | 100-400% FPL | |||

| % | % | % | ||

| No Access to ESI | 84% | 90% | 81%^ | |

| No one in family has an employer1 | 41% | 41% | 41% | |

| Firm doesn’t offer coverage | 38% | 44% | 34% | |

| Not eligible for coverage | 5% | — | — | |

| Access to ESI | 16% | 10% | 19%^ | |

| Cannot afford premium | 12% | 8% | 14% | |

| Don’t think need coverage | — | — | — | |

| Some other reason | 3% | — | — | |

| NOTES: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown. 1 Individuals who are self-employed without other employment are treated as not having an employer. “–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or sample size too small for analysis are not provided. ^ Estimate statistically significantly different from <100% FPL at the 95% confidence level. SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. |

||||

About one in six (16%) uninsured adults in Texas does have access to coverage through an employer, but the majority report that the coverage offered to them is not affordable. Notably, lack of access to employer coverage is particularly high among poor, uninsured adults (90%), a group that generally will not be eligible for financial assistance in gaining coverage under the ACA.

Some of the barriers to employer-sponsored coverage that the uninsured have reported facing in the past are addressed by the ACA. In the future, large employers (>50 workers) will face penalties if they do not offer affordable coverage to their workers.1 Additionally, private premiums can only vary based upon age, location, and tobacco use; health plans may not use annual or lifetime spending caps; and plans must allow dependents on the plan until age 26. However, many uninsured adults in the state may not be captured by these provisions and will continue to lack access to coverage through a job.

low-income adults reported limited access to coverage through Medicaid.

While the state had expanded eligibility to children through Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, Medicaid eligibility for adults in Texas remains very limited. To qualify for Medicaid in Texas, parents must have incomes less than 20% of the poverty level. Adults without dependent children are generally ineligible for Medicaid in Texas unless they qualify due to having a disability. In addition, some individuals eligible for Medicaid remain uninsured because they are not aware that they are eligible for coverage or they face application or enrollment barriers.

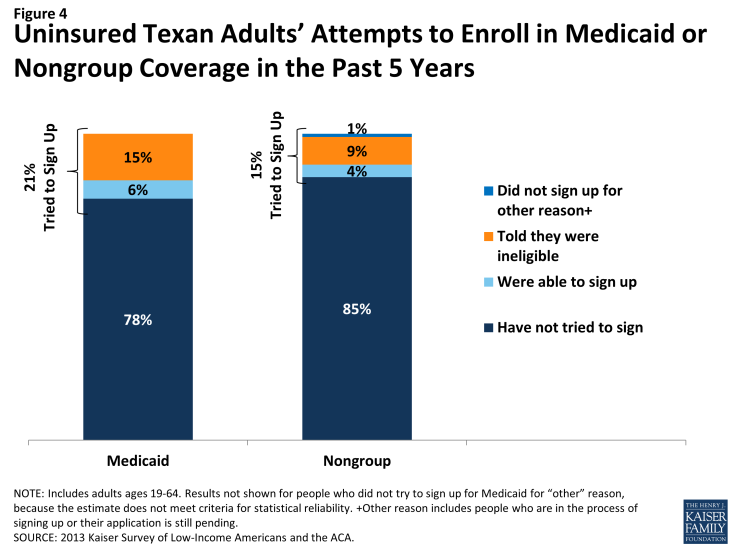

The gaps in Medicaid eligibility for adults and difficulties with the enrollment process pose barriers for many low-income adults seeking coverage. Twenty-one percent of uninsured adults in Texas reported trying to sign up for Medicaid in the past five years (Figure 4). Most uninsured adults in Texas who unsuccessfully tried to enroll in Medicaid (15% of the uninsured) were told they were ineligible (Figure 4). Most of the adults who were told they were ineligible will likely remain ineligible for public coverage, barring a change in their income.

Figure 4: Uninsured Texan Adults’ Attempts to Enroll in Medicaid or Nongroup Coverage in the Past 5 Years

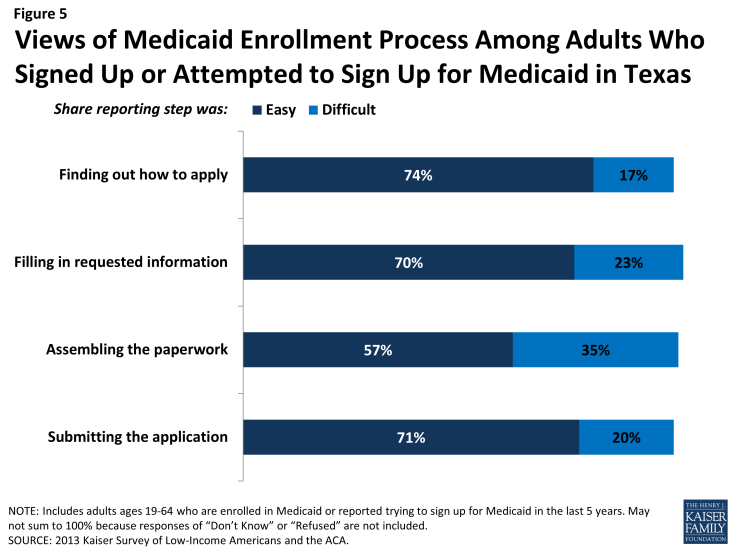

Ineligibility is likely the most substantial barrier that uninsured Texas adults will face in accessing Medicaid coverage. However, enrollment barriers may pose a challenge to enrollment for the small share that are eligible for coverage. Adults in Texas who currently have Medicaid or who have attempted to enroll in the past five years reported little difficulty in enrolling in Medicaid. Over 4 in 10 adults (43%) who applied to Medicaid said the entire process was very or somewhat easy. However, the rest found at least one aspect of the process – finding out how to apply, filling out the application, assembling the required paperwork, or submitting the application – to be somewhat or very difficult. The most commonly reported difficulty was assembling the required paperwork, which over a third (35%) of Texans who enrolled or applied said was somewhat or very difficult (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Views of Medicaid Enrollment Process Among Adults Who Signed Up or Attempted to Sign Up for Medicaid in Texas

About a quarter of Texan adults (24%) who applied to Medicaid in the past five years reported that they did so through traditional routes—that is, in person at a state or county office—and only 17% reported using an online application (Figure 6). The ACA includes provisions to further simplify the application, enrollment, and renewal process for coverage in all states, regardless of whether they expand their Medicaid programs under the ACA. These requirements include the adoption of a single streamlined application that is available online, by phone, and on paper and that screens for all health coverage options; electronic transfers of accounts between agencies to facilitate transitions across health coverage programs; and reliance on trusted sources of electronic data, rather than requesting paper documentation, to verify eligibility criteria.2

Figure 6: Mode of Application Among Adults in Texas Who Signed Up or Attempted to Sign Up for Medicaid

Once simplified enrollment processes are fully implemented, it is possible that people applying for Medicaid in Texas will experience a smoother application and enrollment process than applicants have in the past. However, with Texas not expanding Medicaid and with the state having very low income eligibility for parent coverage, many poor uninsured adults will remain ineligible. Further, as was the case before the ACA, undocumented immigrants remain ineligible to enroll in Medicaid or Marketplace coverage, and recent lawfully residing immigrants are subject to certain Medicaid eligibility restrictions.

Prior to the ACA, there were also barriers to obtaining coverage on the nongroup, or individual, market.

Uninsured Texans also report trying to obtain nongroup coverage in the past. Before the ACA, nongroup coverage was not guaranteed in Texas, and insurance companies could charge higher premiums for sicker or older individuals, making coverage unaffordable for many uninsured adults.3 Fifteen percent of uninsured adults in Texas reported trying to obtain nongroup coverage in the past five years. Most of these Texans (9% of the uninsured) did not purchase a plan because the policy they were offered was too expensive (Figure 4 and Appendix Table A2).

Under the ACA, thousands of uninsured families are now able to purchase coverage in the Marketplace and receive premium tax credits to reduce the cost. In addition, insurers are no longer able to deny coverage based on health status and are limited in what they charge people based on age, location, and tobacco use status. However, as of April 2014, just over 23% of the potential Marketplace population in Texas had enrolled in coverage, lower than the national average of 28%.4 People who have attempted to obtain coverage in the past may have been unaware that rules and costs have changed under the ACA. Indeed, 71% of uninsured Texas adults in the income range for premium tax credits reported knowing only a little or nothing at all about the Marketplace prior to open enrollment.5 Further, there is anecdotal evidence that misinformation about the ACA was pervasive in Texas.6 In more recent months, media coverage of the rocky start to the open enrollment period may have led Texas residents to become more familiar with the presence of the federal marketplace. In the future, outreach and education could help inform people that eligibility rules have changed and that financial assistance is available to offset the cost of coverage.

Access to Health Care Services Among Uninsured Adults in Texas

Uninsured adults in Texas generally do not seek or receive health care services at the same rate as insured adults, even when they have a need for care. Many uninsured adults have substantial health care needs that are not monitored by a physician. Cost is the main reason uninsured Texans do not receive care when needed, and many lack a regular provider to facilitate follow-up or ongoing care. When uninsured adults do receive care, they often have limited options. As coverage expands under the ACA, some uninsured adults are likely to get care more frequently and establish relationships with providers, yet many uninsured adults will remain without a coverage option and continue to have unmet need for care.

A large segment of the uninsured in Texas has little or no connection to the health care system.

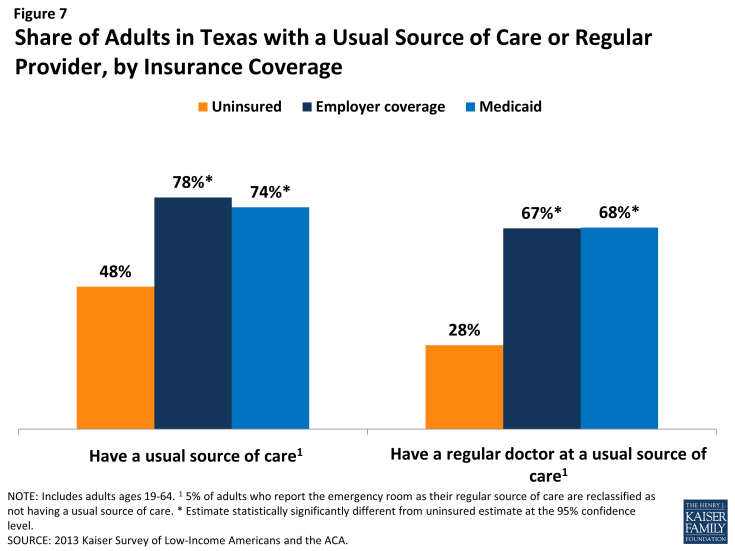

While some uninsured adults in Texas do report receiving health care services, most report few connections to the health care system. Less than half of uninsured adults in Texas (48%) report that they have a usual source of care, or a place to go when sick or need advice about their health (not including the emergency room). Having a usual source of care is an indicator of being linked in to the health care system and having regular access to services. In comparison, nearly all insured adults in Texas —78% of those with employer coverage and 74% of those with Medicaid coverage— have a usual source of care (Figure 7). In addition, uninsured adults in Texas are less likely to have a regular doctor at their usual source of care, with 28% of uninsured adults reported having a regular doctor, well below the rate of insured adults. Notably, poor uninsured adults in Texas, most of whom fall in the coverage gap, are the least likely to have a usual source of care or a regular physician (Table 3).

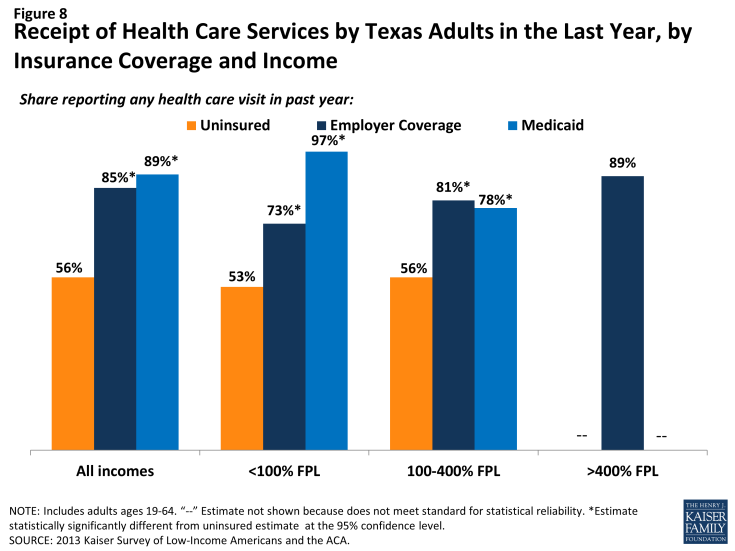

Figure 7: Share of Adults in Texas with a Usual Source of Care or Regular Provider, by Insurance Coverage

This lack of a connection to the health care system leads many uninsured adults in Texas to go without care. About six in ten uninsured adults in Texas (56%) reported a health care visit—including hospital visits, doctor’s office or clinic visits, mental health services, or trips to the emergency room— in the past year, compared to 89% of Medicaid beneficiaries and 85% of adults with employer coverage (Figure 8). Of particular concern is the lack of preventive visits among uninsured adults in Texas. Three in ten (31%) of uninsured adults reported a preventive visit with a physician in the last year, compared to 73% of adults with employer coverage and 71% of adults with Medicaid (data not shown).

Figure 8: Receipt of Health Care Services by Texas Adults in the Last Year, by Insurance Coverage and Income

|

Table 3: Share of Adults in Texas with Usual Source of Care or Regular Provider,

by Income and Coverage

|

||||

| Uninsured | Insured | |||

| Employer | Medicaid | |||

| Has a usual source of care1 | ||||

| All | 48% | 78%* | 74%* | |

| By Income | ||||

| <100% FPL | 43% | 59% | 82%* | |

| 100-400% FPL | 48% | 76%* | 61% | |

| >400% FPL | — | 81% | — | |

| Has a regular provider at usual source of care1 | ||||

| All | 28% | 67%* | 68%* | |

| By Income | ||||

| <100% FPL | 24% | 49%* | 79%* | |

| 100-400% FPL | 28% | 63%* | 51%* | |

| >400% FPL | — | 72% | — | |

| NOTES: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown. “–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or sample size too small for analysis are not provided. 15% of adults who report the emergency room as their regular source of care are reclassified as not having a usual source of care. *Estimate is statistically significantly different from uninsured estimate at the 95% confidence level. SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. |

||||

The survey findings reinforce conclusions based on prior research: having health insurance affects the way that people interact with the health care system, and people without insurance have poorer access to services than those with coverage.1,2,3 The remaining uninsured in Texas are likely to continue to face many of the barriers to health care that they had encountered previously, including a lack of usual sources of care, and a lack of preventative care.

Many uninsured Texans have health needs, many of which are unmet or are being met with difficulty.

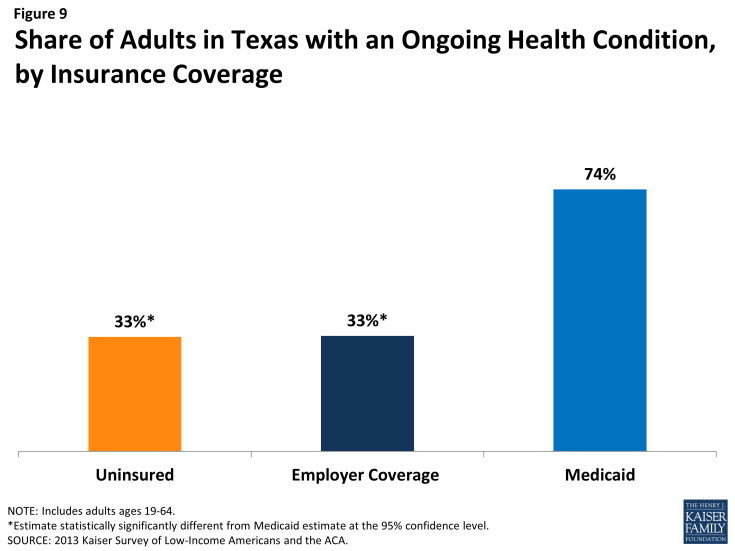

Texans who lack health insurance still have health care needs. About three in ten (33%) uninsured adults reported an ongoing health condition, compared to 74% with Medicaid (Figure 9). Medicaid beneficiaries are most likely to report having an ongoing health condition of all coverage groups, which reflects Medicaid’s role in caring for people with substantial health needs, such as individuals with disabilities or people who become impoverished due to high health care expenses. These findings hold across income groups (Table 4).

| Table 4: Health Status of Adults, by Income and Coverage | ||||||

| Uninsured | Insured | |||||

| Employer Coverage | Medicaid | |||||

| Fair or Poor Overall Health | All Incomes | 40% | 11%* | 67%* | ||

| <100% FPL | 50% | — | 75%* | |||

| 100-400% FPL | 34% | 17%* | 55% | |||

| Fair or Poor Mental Health | All Incomes | 16% | 6%* | 28%* | ||

| <100% FPL | 22% | — | 42%* | |||

| 100-400% FPL | 12% | 11% | — | |||

|

Have ongoing health condition that

needs to be monitored regularly

or needs regular care

|

All Incomes | 33% | 33% | 74%* | ||

| <100% FPL | 31% | — | 84%* | |||

| 100-400% FPL | 29% | 30% | 60%* | |||

| Take prescription medication on regular basis1 | All Incomes | 31% | 44%* | 69%* | ||

| <100% FPL | 33% | — | 80%* | |||

| 100-400% FPL | 27% | 42%* | 50%* | |||

| NOTES: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown. “–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or sample size too small for analysis are not provided. 1Excludes birth control. *Estimate statistically significantly different from uninsured estimate at the 95% confidence level. SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. |

||||||

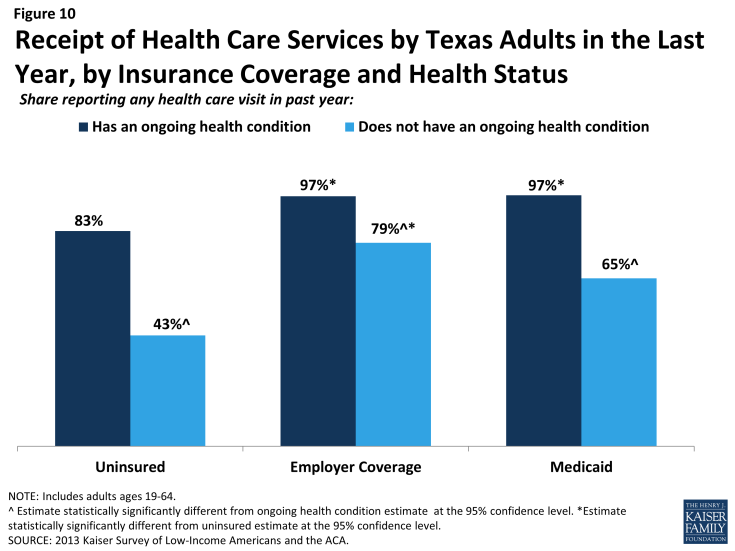

While uninsured Texans with an ongoing health condition are more likely than those without to report receiving services (Figure 10), they are still less likely than their insured counterparts to receive care. Less than half (43%) of uninsured adults without an ongoing health condition say they received health care services in the last year, and more than eight in ten (83%) uninsured adults with a health condition received health care services. However, the latter rate is still lower than adults who have a health condition and have employer coverage or Medicaid, nearly all of whom (97% and 97%, respectively) reported receiving medical services over the course of the year.

Figure 10: Receipt of Health Care Services by Texas Adults in the Last Year, by Insurance Coverage and Health Status

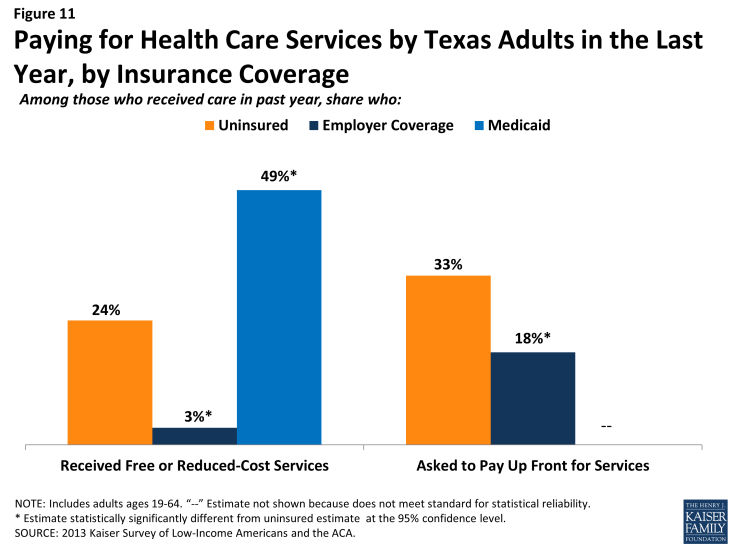

When uninsured Texans do receive care, they sometimes receive free or reduced-cost care, though the majority does not. Among adults in Texas who reported that they received a health care service in the past year, 24% of uninsured adults in Texas reported receiving free or reduced cost care, versus just 3% of those with employer coverage (Figure 11). Notably, 49% of adults with Medicaid who received services reported that they received free or reduced cost care. They may have done so during a period of uninsurance in the previous year or may associate the fact that they pay little or no costs when they see a provider as receiving “free or reduced cost” care. Uninsured adults in Texas who received care were much more likely than their insured counterparts to be asked to pay up front for care: one-third (33%) reported being asked to pay for the full cost of medical care (not counting copayments) before they could see the doctor or provider, compared to just 18% of those with employer coverage. Adults with employer coverage may have experienced these issues during a period in the past year when they lacked coverage or when using a service not covered by their insurance.

Although some uninsured and insured adults in Texas reported receiving free or reduced cost health care services, a larger share reported an unmet need for care. Nearly half (47%) of the uninsured and Medicaid (50%) beneficiaries in Texas reported needing but postponing care, compared to 31% of adults with employer coverage (Figure 12).

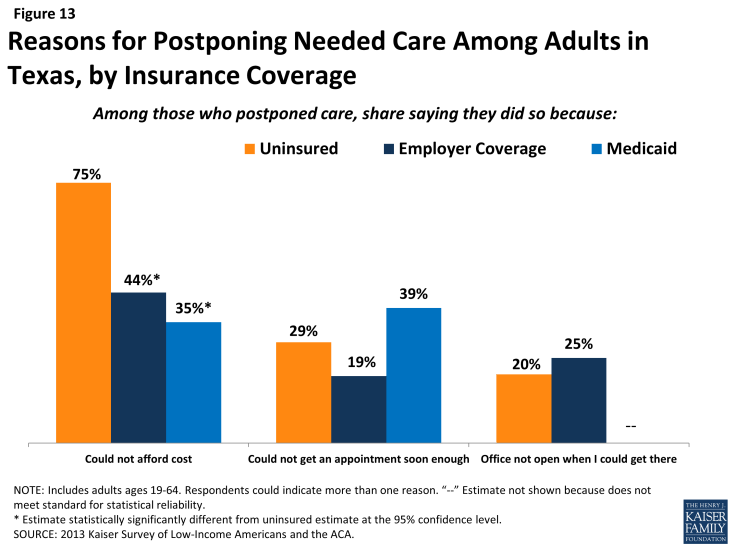

The most common reason for postponing care among uninsured Texans is cost (75%). Adults with employer coverage (44%) or Medicaid (35%) are less likely to report cost as a reason for postponing care because presumably their insurance pays most or all of that cost (Figure 13). However, adults with employer coverage or Medicaid may report postponing care due to cost if their health insurance does not cover a specific treatment that they need. Appointment availability was also reported as a significant reason for postponing care. Almost four in ten adults with Medicaid (39%) and nearly three in ten uninsured adults (29%) reported postponing care because they could not get an appointment soon enough. A quarter of adults with employer coverage reported that the office not being open when they could get there as a reason for postponing. Many physicians do not have hours outside of the normal workday, so some working adults may need to take time off to get care.

As resources and attention shift to the newly-insured population, individuals left out of coverage expansions (such as poor adults) will continue to have health needs. The ACA included funds to expand service capacity in medically underserved areas, including expansion of community health centers, nurse-managed health centers, and school-based clinics. To meet the health care needs of both insured and uninsured individuals, these systems will be challenged to develop flexible treatment times and new models of care to accommodate people’s availability and to expand capacity in areas where low-income individuals reside or seek care.

Many uninsured Texans reported limited options for receiving health care when they need it.

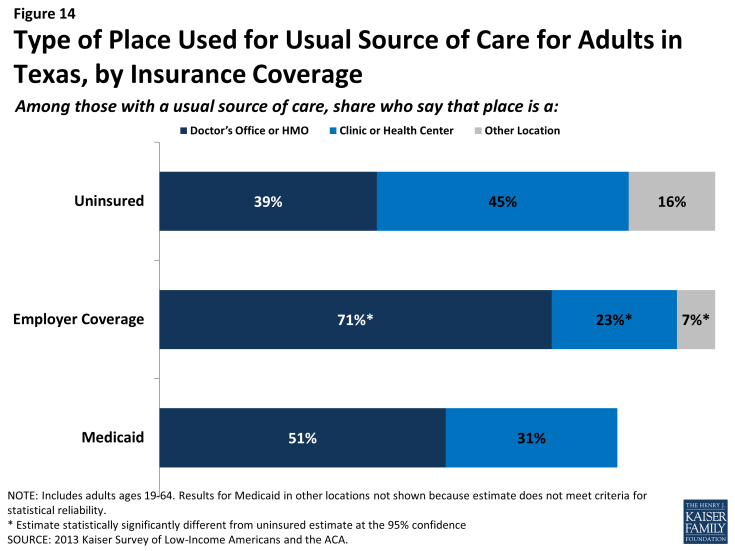

Uninsured adults in Texas are less likely than their insured counterparts to receive care in a private physician’s office. Uninsured adults in Texas are also more likely to go to a clinic or health center than a private physician’s office when receiving care. Nearly four in ten (39%) uninsured Texas adults who have a regular source of care reported that it is a physician’s office or HMO, compared to over seven in ten (71%) of adults with employer coverage (Figure 14). Meanwhile, 45% of uninsured adults in Texas who have a regular source of care reported clinics or health centers as their usual source of care, nearly twice as high as adults with employer coverage (23%). Notably, 17% of uninsured adults in Texas reported the emergency room as their usual source of care – substantially higher than adults with private insurance (data not shown).

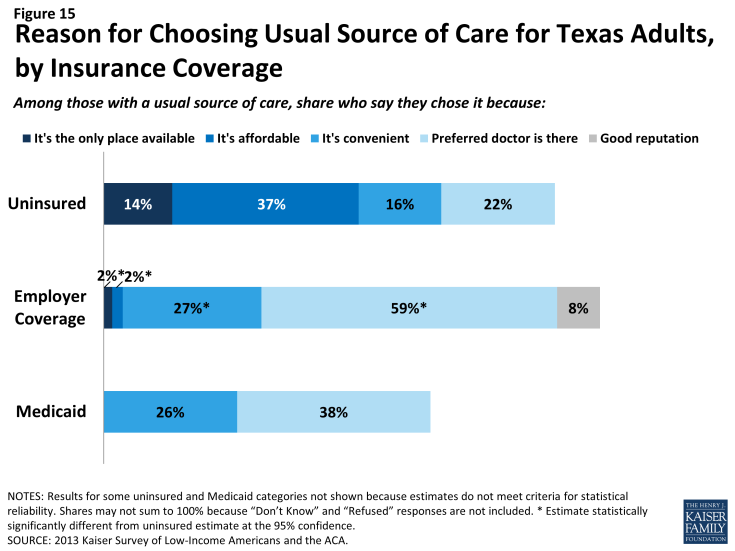

Uninsured adults in Texas are more likely than other adults to report that they have limited options for their usual source of care. Among people with a usual source of care, 37% of the uninsured reported that they chose their usual source of care because it is affordable, compared to 2% with employer coverage (Figure 15). Adults with employer coverage are more likely to choose a site of care based on the ability to see their preferred provider compared to uninsured adults. Most of those who say they chose their usual source of care based on cost chose to go to a clinic or health center, reflecting the fact that these providers often have a mission to serve low-income populations and offer services with sliding scale fees.4

Financial Security Among Uninsured Adults in Texas

Poor and moderate-income families in Texas face multiple financial challenges on a daily basis, but a major challenge is the cost of health care. Poor and moderate -income adults without coverage are particularly vulnerable, facing even more financial strain than their insured counterparts. Both insured and uninsured adults in Texas struggle with medical bills and debt. Coverage expansions, assistance with premium costs, and limits on out-of-pocket costs under the ACA have the potential to ameliorate the financial issues associated with the cost of health care, but many uninsured adults, primarily poor adults, will be left without any assistance.

Health care costs pose a challenge for poor and moderate-income families in Texas, particularly if they are uninsured.

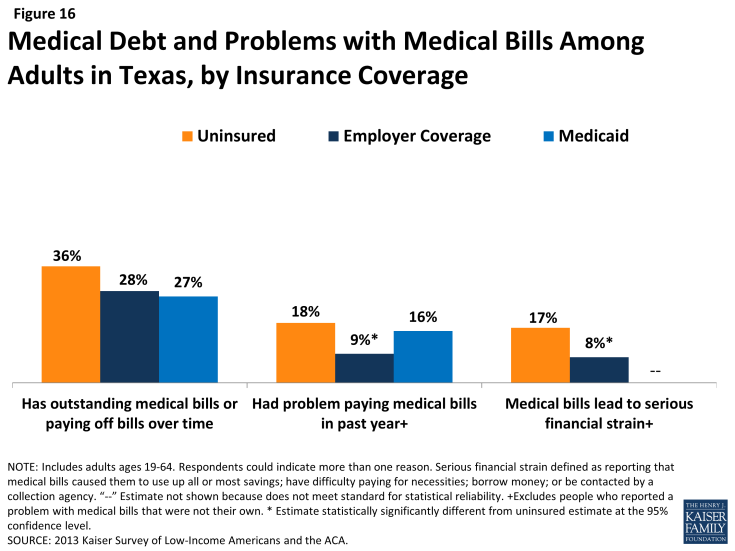

Health care accounts for a major budget item for low-income families, and affordability is a concern for many. Health care costs translate to medical debt for many poor adults. Over a third (36%) uninsured adults in Texas have outstanding medical bills (Figure 16). Notably, many insured Texas adults also report having medical bills that are unpaid or being paid off over time. However, given that the uninsured use less care than the insured, the high rates of medical debt among the uninsured indicate particular financial burden of having to pay the full cost of care on their own.

People may report medical debt but not have a problem paying that debt. However, when asked directly whether they had problems paying medical bills in the past year, notable shares of uninsured adults (18%) and adults with Medicaid (16%) reported that they did (Figure 16). In many cases, the problems people had paying medical bills were severe. Many reported that medical bills caused them to either use up all or most of their savings, have difficulty paying for necessities, borrow money, or be contacted by a collection agency.

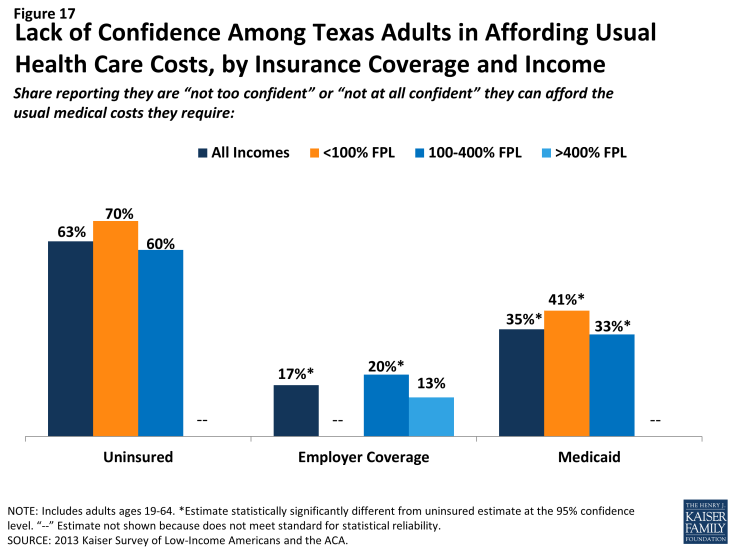

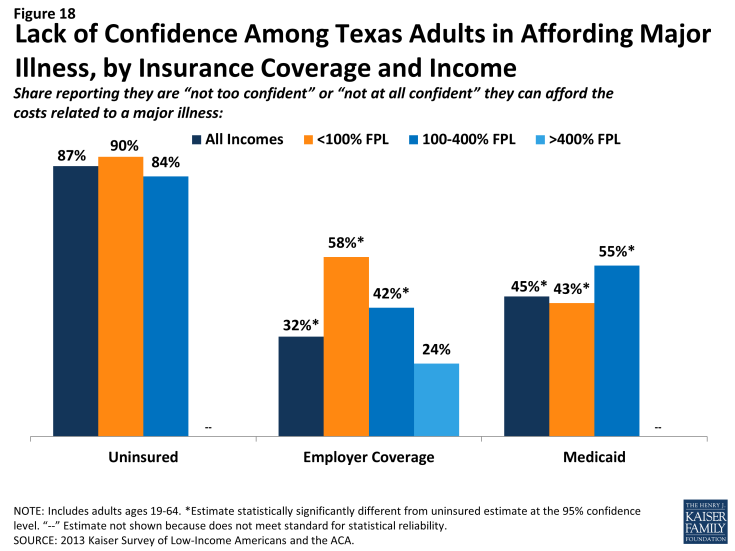

Figure 16: Medical Debt and Problems with Medical Bills Among Adults in Texas, by Insurance Coverage

In addition to many poor adults in Texas reporting that they experienced financial strain or difficulty with health care costs, many live with worry about their ability to afford costs in the future. The vast majority of uninsured Texas adults across all income groups reported that they lack confidence that they can afford either the cost of care for services they typically require (Figure 17) or the cost of care should they face a major illness (Figure 18). While not surprising, this finding indicates that uninsured adults in Texas are aware of the high cost of health care services, as even those with moderate or high incomes do not believe they can afford these costs.

Figure 17: Lack of Confidence Among Texas Adults in Affording Usual Health Care Costs, by Insurance Coverage and Income

Figure 18: Lack of Confidence Among Texas Adults in Affording Major Illness, by Insurance Coverage and Income

Affordability provisions in the ACA could ameliorate some of the challenges that poor insured Texans face in affording care. Under the law, qualified health plans must cover preventive services with no cost sharing and are prohibited from placing annual or lifetime caps on the dollar value of insurance coverage. In addition, plans may not exclude coverage for pre-existing conditions, which often were excluded from nongroup plans in the past and may have led to high out-of-pocket costs for insured individuals. Last, Texans who purchase coverage through the Texas Marketplace and have incomes up to 400% FPL receive tax credits to help them pay for their premiums, and those with incomes up to 250% FPL also receive subsidies to help with cost sharing under their plans. However, given survey findings that many poor insured people continue to face financial challenges related to health care, people may perceive even limited out-of-pocket costs to be unaffordable. It will be important to track whether there are ongoing financial barriers as people enroll in coverage and seek care. Further, many poor uninsured adults in the state will remain ineligible for financial assistance and are likely to continue to face financial hardship due to health care costs.

Uninsured adults living in poverty face fragile financial circumstances.

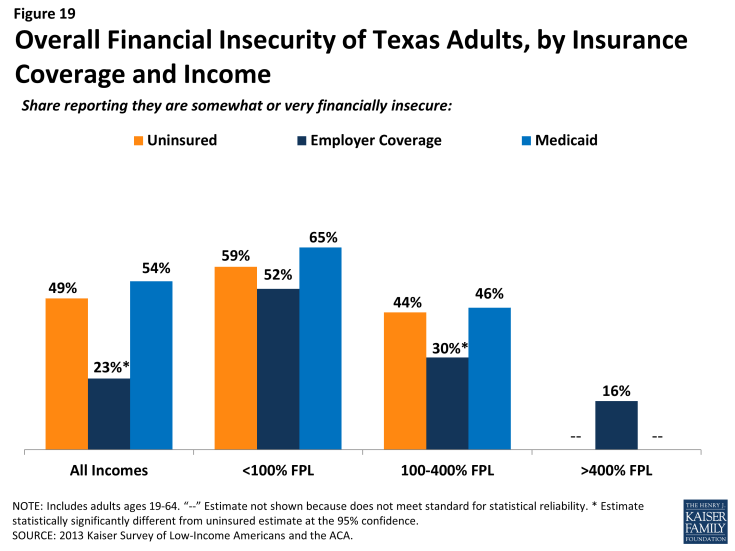

Difficulty or worry about paying for health care translates to expenses in other areas as well, and poor and moderate-income adults across coverage groups reported not being financially secure. However, adults in Texas who are poor and uninsured or covered by Medicaid are particularly vulnerable to financial insecurity even outside of health care. Among those with incomes <100% FPL, almost six in ten uninsured adults (59%) reported that they feel generally financially insecure (Figure 19). Notably, there are no significant differences across coverage groups among poor adults. This pattern may reflect the tenuous financial situation of adults with incomes below 100% FPL, regardless of insurance.

Figure 19: Lack of Confidence Among Texas Adults in Affording Major Illness, by Insurance Coverage and Income

General financial insecurity translates to concrete financial difficulties in making ends meet. Uninsured adults and those enrolled in Medicaid are more likely than those with employer coverage to have difficulty paying for other necessities, such as food, housing, or utilities, with 58% and 67%, respectively, reporting such difficulty, compared to 20% of those with employer coverage (Table 5). While poor adults (<100% FPL) in Texas across the coverage spectrum reported high rates of difficulty paying for necessities, those with employer coverage reported the lowest rates in this income group. These individuals may have the stronger or more stable ties to employment than their counterparts with other or no insurance coverage. A similar pattern holds for people’s ability to get ahead financially, either saving money or paying off debt.

Large shares of adults across income and coverage groups have also reported that they have taken on debt or taken money out of their savings to pay bills in the past year. About a third of uninsured adults and of those enrolled in Medicaid report changing their living situation or postponing marriage or children for financial reasons (Table 5).

| Table 5: Financial Difficulty Among Adults in Texas, by Income and Coverage | ||||

| Uninsured | Insured | |||

| Employer | Medicaid | |||

| Has difficulty paying for necessities | ||||

| All incomes | 58% | 20%* | 67% | |

| <100% FPL | 68% | 53% | 84%* | |

| 100-400% FPL | 54% | 24%* | 53% | |

| >400% FPL | — | 14% | — | |

| Has difficulty saving money | ||||

| All incomes | 84% | 49%* | 83% | |

| <100% FPL | 89% | 83% | 85% | |

| 100-400% FPL | 80% | 57%* | 86% | |

| >400% FPL | — | 40% | — | |

| Has difficulty paying off debt | ||||

| All incomes | 58% | 37%* | 53% | |

| <100% FPL | 62% | 71% | 65% | |

| 100-400% FPL | 55% | 41%* | 48% | |

| >400% FPL | — | 31% | — | |

| Taken on debt or took money out of savings to pay bills | ||||

| All incomes | 47% | 40% | 36% | |

| <100% FPL | 41% | 41% | 23%* | |

| 100-400% FPL | 51% | 44% | 57% | |

| >400% FPL | — | 38% | — | |

| Changed living situation or postponed marriage/children for financial reasons | ||||

| All incomes | 33% | 21%* | 31% | |

| <100% FPL | 34% | 42% | 35% | |

| 100-400% FPL | 33% | 21%* | — | |

| >400% FPL | — | 18% | — | |

| Notes: “–“: Estimates with relative standard errors > 30% or sample size too small for analysis are not provided. *Estimate statistically significantly different from uninsured estimate at the 95% confidence level. SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. |

||||

Though it is not surprising that many poor families are in a precarious financial situation, it is notable that poor adults who lack insurance coverage or who were covered by Medicaid before the ACA are more financially unstable than their privately-insured counterparts. This finding is of particular concern given many poor adults remain ineligible for Medicaid in the state. In Texas, Medicaid coverage for adults is targeted to those with the greatest need, and this role is reflected in the fact that they face similar financial challenges as their uninsured counterparts. While insurance coverage can provide financial protection in the event of illness or injury, it is not curative of all of the financial burdens faced by poor families. Given their overall situation, health insurance alone may not lift poor people out of poverty, and many poor adults may continue to face financial challenges even after gaining coverage. Coverage under the ACA may help address some of the consequences of financial instability among moderate-income families, and linking adults with other support systems may help address the broader financial challenges that they face.

Policy Implications

The survey findings have implications for early implementation of the ACA in Texas and for ongoing policy development in the state. Uninsured adults in Texas are generally in low-income, working families and have lacked insurance coverage for quite some time. Most do not have access to coverage through their jobs, and many have unsuccessfully tried to enroll in coverage in the past. Many uninsured adults in Texas have substantial health care needs but have only loose ties to the health system, facing considerable barriers in trying to access care when they need it.

Removing Some Barriers to Health Insurance and Care

Many ACA provisions may facilitate moderate-income adults’ access to health insurance in Texas. Large employers will face penalties if they do not provide coverage to their workers, and insurers may not deny coverage based on health status and history. In addition, private premiums can only vary based upon age, location, and tobacco use, and health plans may not use annual or lifetime spending caps. Texans who purchase health plans through the Marketplace, and have incomes between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level, may receive tax credits to help them pay for premiums, with those who have incomes between 100% and 250% of the federal poverty level also eligible for subsidies to aid with the cost sharing. The survey results indicate that these provisions may address many of the barriers that Texans have faced in accessing coverage, such as not having coverage through a job, not being able to afford coverage, or having a health condition that might price them out of the market. While open enrollment has ended for Marketplace coverage in 2014, as of November people can sign up for Marketplace plans to begin in 2015.

Not expanding Medicaid limits the coverage options for poor Texans. Because Texas is not expanding Medicaid, over a million uninsured Texans who would have been eligible for Medicaid fall into the coverage gap. They are not eligible for the Marketplace subsidies and tax credits, most do not have access to coverage through a job, and they likely are unable to afford coverage on their own. These remaining uninsured adults are likely to continue to face the access to care issues that they currently face by being unlinked to the health care system. The survey shows that currently less than half of the uninsured have a usual source of care, and even uninsured Texans with an ongoing health condition face barriers to receiving care compared to their insured counterparts.

Although Texas is not expanding Medicaid, the ACA does include other provisions that affect low-income Texas residents who were already eligible for Medicaid. The survey shows that 35% of adults who attempted to sign up for Medicaid found assembling the paperwork difficult. The ACA included provisions to simplify the Medicaid application, enrollment, and renewal processes. These requirements included implementing a single application that is available online, by phone, and on paper; electronic transfers of accounts between health coverage programs; and reliance on electronic data to verify eligibility, rather than requiring paper documents. These provisions may lead to smoother enrollment and renewal in the Medicaid program.

Reaching Eligible Uninsured Adults

There are many challenges to reaching uninsured adults who are eligible for coverage under the ACA. Some uninsured adults in Texas may be hard to reach as part of outreach efforts: many do not speak English, and the eligible population is very diverse. Over half (56%) of the uninsured identify as Hispanic and 40% are under age 35. Additionally, many families have mixed citizenship status, and effectively reaching these families and building enough trust to enroll the eligible in health insurance is a challenge. Many uninsured Texan adults have been outside the insurance and health care system for quite some time and may not be easily reached through traditional avenues.

Outreach and enrollment is an ongoing process. While there was much focus on the initial push to enroll people in coverage under the ACA, enrollment is not a “one shot” effort that will be completed in the first few months of implementation. The survey findings reveal that nearly one in five (19%) of Texans lose and gain coverage throughout the year because of job changes, income fluctuations, or problems at renewal. Thus, implementing the ACA is an ongoing effort to enroll and keep people in coverage.

The Continuing Role of Safety Net Providers in Texas

Many people will remain without coverage in Texas. Uninsured residents access health care less frequently than insured individuals, often forgoing preventive care measures. The survey shows that nearly half (47%) of the uninsured postponed needed care in the previous year, and three quarters of those uninsured who postponed care did so because of the cost. The low-income uninsured are particularly vulnerable, as they face even more financial strain when they do get sick than their insured counterparts. Many uninsured adults rely on federally qualified health centers and public hospitals when they do access care. However, many health centers are already operating at capacity, and these facilities are generally not equipped to provide specialty care. Additionally, DSH funding will be reduced in next several years. It will be important to monitor how well the safety net in Texas is able to meet the continuing and growing demand for services in this context.

Methodology

This report is based on findings from the Texas component of the 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. This survey, conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), examines health insurance coverage, health care use and barriers to care, and financial security among insured and uninsured adults across the income spectrum, with a focus on populations targeted for coverage expansions under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The survey provides a baseline against which future surveys can assess the impact of the ACA on low- and moderate-income adults. The 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA includes a national sample as well as three state-specific samples in California (conducted with support the Blue Shield of California Foundation (BSCF)), Missouri (conducted with support from Missouri Foundation for Health (MFH)), and Texas.

The survey was designed and analyzed by researchers at KFF, with feedback on the California and Missouri state-specific components from BSCF and MFH, respectively. Social Science Research Solutions (SSRS) collaborated with KFF researchers on sample design and weighting; SSRS also supervised the fieldwork.

The survey was conducted by telephone from July 24 through September 29, 2013, from a representative random sample of Texas residents between the ages of 19-64. In total, 1,809 interviews were completed with respondents living in Texas. Computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI) conducted by landline (892) and cell phone (917) were carried out in English and Spanish by SSRS.

Because the study was designed to focus on the low-income population, the sample was designed to over-sample this group. To efficiently reach lower-income respondents, the sample was stratified based on the estimated income level of geographic areas within the state. This process was done separately for the landline and cell phone sampling frames. For the landline sample, strata were defined based on the median income within telephone exchanges; for the cell phone sample, strata were defined based on the household income associated with the billing rate-center to which the cell phone number is linked. The exact criteria for distinguishing between the strata varied from state to state. In addition, a small number of interviews (<1% of the total sample) were conducted with respondents who were previously interviewed by SSRS as part of omnibus surveys of the general public and indicated they were ages 19-64, resided in the state, and reported annual income of less than $25,000. These previous surveys were conducted with nationally representative, random-digit-dial landline and cell phone samples.

Screening for the survey involved verifying that the respondent (or another member of the household for the landline sample) met the criteria of: 1) being 19-64 years old; and 2) providing income information that allowed them to be classified by family income. Respondents were classified by family income as a share of the federal poverty level (FPL) based on their family size and total annual gross income.1 Poverty level groups included income < 138% of FPL (the income range for the Medicaid expansion), income of 139-400% FPL (the income range for Marketplace tax credits), and income of over 400% FPL (eligible only for unsubsidized coverage). For the landline sample, if two or more people met the criteria, a respondent was randomly selected by the CATI program. Selected respondents were asked to confirm their state of residence.

A multi-stage weighting approach was applied to ensure an accurate representation of the various income groups ages 19 to 64. The weighting process involved corrections for sample design as well as sample weighting to match known demographics of the target populations in order to correct for systematic non-response along these parameters. The base weight accounted for the oversamples used in the sample design, as well as the likelihood of non-response for the re-contact sample, number of eligible household members for the landline sample, and a correction to account for the fact that respondents with both a landline and cell phone have a higher probability of selection. Demographic weighting parameters were based on population estimates for the 19-64 year old poverty-level population in the state based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2011 American Community Survey (ACS). The weighting parameters for each poverty-level group were: age, education, race/ethnicity, presence of own child in the household, marital status, region, and phone-status. All statistical tests of significance account for the effect of weighting.

The number of respondents and margin of sampling error (including the design effect) for the entire Texas sample and for subgroups based on income are shown in Table A. For results based on other subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher. Sample sizes and margin of sampling errors for other subgroups are available by request. In reporting results, any estimate with a relative standard error (standard error divided by the point estimate) greater than 30% is considered unreliable and not reported. Note that sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error in this or any other survey.

| Table A: Number of Respondents and Margin of Sampling Error for Texas Sample | ||

| N | Margin of Sampling Error | |

| Texas Total | 1,809 | +/- 4 percentage points |

| <138% FPL | 754 | +/- 6 percentage points |

| 139% – 400% FPL | 753 | +/- 5 percentage points |

| >400% FPL | 302 | +/- 8 percentage points |

In analyzing results, we group respondents into the mutually exclusive insurance categories of: Uninsured (report that they are not covered by health insurance), Employer Coverage (report that they have a plan through their own employer, a spouse’s employer, or a parent’s employer), and Medicaid (including people who are dually eligible for Medicare coverage). In capturing Medicaid coverage, the state-specific program name was used. A small number of people report that they are covered by other sources, including Medicare (<5%), a government program besides Medicaid or Medicare (<3%), or some other source such as the VA, school-based coverage, or an unnamed source (<3%). We do not report results for people covered by these other coverage categories, as sample sizes were generally too small for reliable estimates.

Because eligibility for two of the law’s main coverage provisions– the Medicaid expansion and tax credits to purchase insurance through Marketplace– is based on an individual’s family income relative to the federal poverty level (FPL), we report survey results by FPL categories that match eligibility levels under the ACA. In Texas, these categories are 1) those with incomes under 100% FPL or less (roughly $20,000 a year for a family of 3); 2) those with incomes of 100 to 400% FPL (roughly $20,000-$79,000 for a family of 3), the income range for tax credits in the Marketplace; and 3) those with incomes above 400% FPL, who are not be eligible for financial assistance in gaining coverage. These classifications are not intended to fully capture eligibility, as not everyone in these income ranges will be eligible for coverage under the ACA. For example, undocumented immigrants are ineligible for coverage under the ACA, and recent legal immigrants with incomes below poverty can purchase subsidized coverage through the Texas Marketplace. In addition, some people may be ineligible for premium subsidies through the Texas Marketplace because they have access to affordable employer coverage. However, the income categories provide a picture of the population targeted by various expansions, rather than a picture of the specific population eligible under the law.

We define undocumented immigrants as those who reported 1) they were born outside the United States, 2) are not a citizen, 3) did not have a green card when they arrived in the United States, and 4) have not received a green card or become a permanent resident since arriving. This measure may be subject to error in several ways. First, it relies on self-reporting, and respondents have an incentive not to reveal unlawful immigration status. Second, those that did not answer all questions in the series of immigration status items (3 respondents) were not able to be categorized and were therefore included; if they are in fact undocumented, then the results may differ slightly. Third, a small number of people may have a legal status besides permanent residency or green card (such as refugees, asylees or other humanitarian immigrants). Unfortunately, due to time constraints, the survey was not able to fully explore all of these immigration pathways.

This report includes analysis of findings from the survey that may inform early challenges in implementing health reform. It does not include a full reporting of all the findings from the survey. Survey toplines with overall frequencies for all items in the questionnaire are available upon request.

Appendix

Additional Tables

| Table A1: Demographics of Adults in Texas, by Insurance Coverage | |||

| Uninsured | Insured | ||

| Employer | Medicaid | ||

| Income | |||

| <100% FPL | 40% | 5%* | 51% |

| 100-400% FPL | 54% | 39%* | 42% |

| >400% FPL | 6% | 56%* | — |

| Family Work Status | |||

| Working Family | 69% | 92%* | 23%* |

| Non-Working Family | 31% | 8%* | 77%* |

| Age | |||

| 19-25 | 16% | 14% | — |

| 26-34 | 24% | 19% | — |

| 35-44 | 29% | 22% | 26% |

| 19-44 | 69% | 55%* | 44%* |

| 45-64 | 31% | 45%* | 56%* |

| Health Status | |||

| Ongoing Health Condition | 33% | 33% | 74%* |

| No Ongoing Health Condition | 66% | 67% | 25%* |

| Fair or Poor Health Status | |||

| Excellent/Very Good/Good | 59% | 89%* | 33%* |

| Fair or Poor | 40% | 11%* | 67%* |

| Race | |||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 30% | 58%* | 28% |

| Hispanic | 56% | 24%* | 50% |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 11% | 10% | 15% |

| Citizenship | |||

| Citizen | 62% | 94%* | 86%* |

| Non-Citizen | 38% | 6%* | — |

| Notes: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown. “–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or sample size too small for analysis are not provided. * Estimate statistically significantly different from uninsured estimate at the 95% confidence level. Source: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. |

|||

| Table A2: History of Uninsurance and Attempts to Gain Coverage Among Currently Uninsured Adults in Texas, by Income | ||||

| All | By Income | |||

| <100% FPL | 100-400% FPL | |||

| Length of Time Uninsured | ||||

| < 3 months | 6% | — | 6% | |

| 3 Months to Less than a Year | 11% | 9% | 11% | |

| 1 Year to 5 years | 29% | 22% | 33%^ | |

| 5 Years or More | 22% | 18% | 25% | |

| Have Never Had Coverage | 31% | 44% | 24%^ | |

| Attempts to Gain Coverage | ||||

| Applied for Medicaid in past 5 years | 22% | 25% | 20% | |

| Applied for Medicaid but did not enroll | 16% | 16% | 15% | |

| Applied for Medicaid but told ineligible | 15% | 13% | 15% | |

| Tried to purchase nongroup coverage in past 5 years | 15% | 12% | 16% | |

| Tried to purchase nongroup coverage but did not purchase policy | 11% | 8% | 13% | |

| Tried to purchase nongroup coverage but too expensive | 9% | 6% | 11% | |

| NOTES: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown. “–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or sample size too small for analysis are not provided. NA: Not applicable. Estimates not shown for >400% as estimates do not meet criteria for statistical reliability. ^ Estimate statistically significantly different from <100% FPL estimate at the 95% confidence level. SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. |

||||

Endnotes

Report

Introduction

“Marketplace Enrollment as a Share of the Potential Marketplace Population” https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/marketplace-enrollment-as-a-share-of-the-potential-marketplace-population/.

Kaiser Family Foundation, “The Uninsured: A Primer” (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2013), https://www.kff.org/uninsured/report/the-uninsured-a-primer-key-facts-about-health-insurance-on-the-eve-of-coverage-expansions/.

Ibid.

See “Protections in individual insurance markets” at https://www.kff.org/state-category/health-insurance-managed-care/.

Based on data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), State Medicaid and CHIP Income Eligibility Standards Effective April 1, 2014.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Texas Medicaid.

Characteristics of Uninsured Adults in Texas

“2014 Poverty Guidelines” (Office of The Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation) http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/14poverty.cfm.

Adults who qualify through a disability pathway may have higher income levels than adults who qualify through a parent pathway.

These percentages are possibly over-estimates, as the survey is unable to differentiate between undocumented immigrants and residents with refugee or asylee status.

Patterns of Coverage Among Adults in Texas

“Getting Coverage outside Open Enrollment” https://www.healthcare.gov/how-can-i-get-coverage-outside-of-open-enrollment/#part=2.

Access to Coverage Among Uninsured Adults in Texas

On February 10, 2014, the Obama Administration delayed penalties associated with this Employer Responsibility Provision until 2015. U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury and IRS Issue Final Regulations Implementing Employer Shared Responsibility Under the Affordable Care Act for 2015” (February 10, 2014). http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl2290.aspx.

For more information, see: M. Heberlein, T. Brooks, S. Artiga, and J. Stephens, “Getting into Gear for 2014: Shifting New Medicaid Eligibility and Enrollment Policies into Drive”(Washington DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, November 2013). http://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/getting-into-gear-for-2014-shifting-new-medicaid-eligibility-and-enrollment-policies-into-drive/.

See “Protections in individual insurance markets” at https://www.kff.org/state-category/health-insurance-managed-care/.

Excludes undocumented immigrants.

B. Aaronson, “Advocates Target Latinos in ACA Enrollment Outreach.” (The Texas Tribune, October 14, 2013). http://www.texastribune.org/2013/10/14/advocates-target-latinos-aca-enrollment-outreach/.

Access to Health Care Services Among Uninsured Adults in Texas

Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance, Board on Health Care Services, “Care without Coverage: Too Little, Too Late” (Washington DC: National Academy Press: Institute of Medicine, May 2002). http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2003/Care-Without-Coverage-Too-Little-Too-Late/Uninsured2FINAL.pdf.

Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance, Board on Health Care Services “Coverage Matters: Insurance and Health Care” (Washington DC: National Academy Press: Institute of Medicine, 2001).

J. Paradise and R. Garfield, “What is Medicaid’s Impact on Access to Care, Health Outcomes, and Quality of Care? Setting the Record Straight on Evidence”(Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, August 2, 2013). https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/what-is-medicaids-impact-on-access-to-care-health-outcomes-and-quality-of-care-setting-the-record-straight-on-the-evidence.

Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, “Community Health Centers in an Era of Health Reform: An Overview and Key Challenges to Health Center Growth”(Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 1, 2013). https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/community-health-centers-in-an-era-of-health-reform-overview/.

Methodology

In capturing family size, we include all members of the respondents’ immediate family, including themselves, spouse (if married), and any dependents, as well as parents if the respondent is a dependent. These groupings mimic “health insurance units” that are used to determine eligibility for Medicaid and Marketplace coverage.