Tax Subsidies for Private Health Insurance

Matthew Rae, Gary Claxton, Nirmita Panchal, and Larry Levitt

Published:

Introduction

The federal and state tax systems provide significant financial benefits for people with private health insurance. The largest group of beneficiaries is people who enroll in coverage through their jobs. There also are tax benefits for people who are self-employed and for people with high medical costs. Recently, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) provided for new premium tax credits to assist low and moderate income families purchasing coverage directly from insurers (nongroup coverage).

The value of these tax benefits is substantial. The largest tax subsidy for private health insurance — the exclusion from income and payroll taxes of employer and employee contributions for employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) – was estimated to cost approximately $250 billion in lost federal tax revenue in 2013.1 The new premium tax credits under the ACA were estimated by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to cost $45 billion in 2014, and increase to $146 billion in 2017, as more individuals enrolled in subsidized coverage.2 In addition, the federal tax deduction for health expenses (including premiums) exceeding 10% of the adjusted gross income is estimated to cost $12.4 billion in lost tax revenue in 2014.3

Despite the important role that the tax system plays in subsiding private coverage, the amount of the benefit received by individuals and families is often not well understood because the tax code is complex, and the value that families receive from tax exclusions and other tax subsidies can vary substantially with income and individual circumstances. Another complicating factor is that the largest tax incentive for private insurance — the exclusion of the cost of ESI — is an indirect subsidy that is never actually reported to the individuals and families who benefit from it. Many people with employer coverage are probably not aware that the federal and state tax exclusions for private health insurance provides them with a subsidy worth several thousands of dollars a year.

In this brief we describe the different forms of tax assistance for private health insurance and provide examples of how they work and how the amounts may differ by income and type of coverage. The examples focus on taxes for 2012, the latest year for which the tax simulation model we used provides complete estimates.4 The model estimates a household’s state and federal taxes based on relevant details, including income and deduction. Tax credits available for non-group coverage were estimated using the Kaiser Family Foundation subsidy calculator.5

Issue Brief

I. Federal and State Tax Exclusions for ESI

Federal and state tax laws do not include the value of employer contributions for health insurance (or health benefits when paid directly by employers) in the income of employees. Employees often also can make their contributions towards the premium for ESI with income before it is taxed. This lowers the amount employees owe in income taxes, and lowers payroll taxes paid for Medicare and Social Security (collectively known as FICA, or the Federal Insurance Contributions Act taxes).1 The exclusions of employer and employee contributions from income and payroll taxes are the largest tax subsidy for private health insurance. We follow with some examples to show how the exclusions work and show how it ranges in value for families in different circumstances.

Exclusion of Employer Premium Contributions for ESI

This first example looks solely at employer contributions for health insurance. For simplicity, it looks only at federal income and payroll taxes and is illustrated in Table 1. Person A works at a job and is paid wages of $60,000. Person A’s employer does not provide health insurance. Person B works at a job and in addition to being paid $50,000 in wages, receives a $10,000 contribution to an employer-sponsored health plan. In this example, the value of Person B’s health insurance policy is $12,500. So, the employer pays $10,000 and Person B pays the remaining $2,500 from his/her wages.

| Table 1: Compensation and Tax Liabilities of Two Workers: With and Without Health Insurance | |||

| Person A (without health insurance) |

Person B (with health insurance) |

Difference (Person A – Person B) |

|

| Total Compensation | $60,000 | $60,000 | $0 |

| Taxable Wages | $60,000 | $50,000 | $10,000 |

| Employer Contributions to Health Insurance Premiums | $0 | $10,000 | ($10,000) |

| Taxes (Total Tax Liability) | $13,245 | $10,215 | $3,030 |

| Federal Income Taxes | $4,065 | $2,565 | $1,500 |

| Employer FICA Assessment | $4,590 | $3,825 | $765 |

| Employee FICA Assessment | $4,590 | $3,825 | $765 |

| NOTE: This analysis assumes a couple filing jointly with two dependents and no other deductions. | |||

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation’s Analysis of the National Bureau of Economic Research’s “Internet TAXSIM, Version 9”. | |||

Both Person A and Person B receive $60,000 total in compensation, but they owe different amounts in taxes. Since Person B receives $10,000 of his/her compensation as contributions towards a health insurance premium, which is excluded from a person’s taxable income, he/she pays $3,030 less in taxes. Person A would pay income tax and FICA based on a $60,000 salary (a total of $9,180 in FICA and $4,065 in income tax).2 In contrast, Person B would pay taxes on $50,000, meaning they would be responsible for $1,500 less in federal income tax and $1,530 less in employer and employee FICA assessments. The total reduction in tax burden ($3,030) is equal to about 30% of the employer premium contribution ($10,000). Note here that while the employer actually pays one-half of the FICA taxes, it is generally accepted that the incidence of the whole tax falls on the employee because it is a nondiscretionary cost that is tied directly to earnings. We therefore treat the extension as benefiting the employee rather than the employer.

Exclusion of Employee Premium Contributions for ESI

In the example above, Person B paid for his/her share of the total health insurance premium from his/her take-home pay. Section 125 of the Internal Revenue Code permits employers to sponsor arrangements that allow employees to pay for their share of insurance premiums with funds deducted from their wages before they are taxed.3 Section 125 plans can be used by employees for a wide variety of benefits including medical expenses, as well as, ancillary benefits like life insurance or vision coverage. Since their inception in 1978, Section 125 plans have become quite common; in 2012, 41% of small firms (3 to 199 workers) and 91% of larger firms offered such an arrangement.4 Section 125 plans allow covered employees to further reduce their tax liability. Table 2 compares the tax liabilities of two employees receiving $10,000 in employer contributions towards a health insurance policy – one whose employer does not offer a Section 125 plan (Person B1) and one whose employer does (Person B2).

| Table 2: Compensation and Tax Liabilities of Two Workers Offered Health Insurance: With and Without a Section 125 Plan | |||

| Person B1 (without 125 plan) |

Person B2 (with 125 plan) |

Difference (Person B1 –Person B2) |

|

| Total Compensation | $60,000 | $60,000 | $0 |

| Taxable Wages | $50,000 | $47,500 | $2,500 |

| Employer Contributions to Health Insurance Premiums | $10,000 | $10,000 | $0 |

| Employee Contribution to Health Insurance through 125 arrangement | N/A | 2500 | ($2,500) |

| Taxes | $10,215 | $9,458 | $758 |

| Federal Income Taxes | $2,565 | $2,190 | $375 |

| Employer FICA | $3,825 | $3,634 | $191 |

| Employee FICA | $3,825 | $3,634 | $191 |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation’s Analysis of the National Bureau of Economic Research’s “Internet TAXSIM, Version 9”. | |||

Since Person B2 is able to pay the $2,500 employee premium share through a Section 125 plan, Person B2’s taxable wages falls from $50,000 to $47,500. This translates to federal income tax liability falling by $375, and employer and employee federal payroll taxes each falling by $191, for a combined tax reduction in federal taxes of $758.5 This tax reduction is approximately 30% of the employee’s share of the premium contribution. A worker in a state with an income tax would see additional savings.6

The impact of these tax exclusions is larger when comparing the tax liability of Person B2, who has a section 125 plan and an employer contribution, to Person A from Table 1 who received all of his/her compensation as wages. Although both Person A and Person B2 each receive $60,000 in total compensation, Person B2 is responsible for $3,788 less in taxes than Person A due to tax treatment for ESI ($3,030 for the employer contribution and $758 for the section 125 contribution).

Impact of Exclusion for Employer and Employee Premium Contributions by Income

The previous examples demonstrate that the exclusion of employer-sponsored health insurance premiums reduces tax liability. In this section, we illustrate the following two reasons why these tax reductions vary by household income, namely:

- Progressive income tax schedules, particularly for federal income taxes.

- Annual caps on the portion of federal payroll tax payments that support the Social Security program.

I. Progressive Income Tax Schedules

Under the federal income tax system, the percentage of income that is taxed increases for each portion of income that exceeds predefined thresholds. Table 3 shows the federal income tax rates for married families filing jointly in 2012. Under the schedule, a family with $75,000 of taxable income7 would pay a tax equal to 10% of the first $17,400 of income (or $1,740), 15% of their next $53,300 of income (or $7,995) and 25% of the last $4,300 of income (or $1,075), for a total tax payment of $10,810. What this means for the tax exclusion for premium payments is that the value of the exclusion grows as income increases. For example, a family with $75,000 of taxable income would save $0.25 in federal income tax for each dollar reduction in their taxable income, but a family with $50,000 in taxable income would save only $0.15 in federal taxes for each dollar reduction in taxable income. The percentage rate at which the last dollar of family income is taxed is referred to as the family’s marginal tax rate. In addition to federal tax, many states have progressive income schedules.

| Table 3: Income Tax Brackets, Tax Rates, and Taxable Income, Married Couples, 2012 | |||

| Taxable Income Bracket | Tax Rate | Taxable Income | |

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||

| $0 | $17,400 | 10% | 10% of the amount over $0 |

| $17,400 | $70,700 | 15% | $1,740 plus 15% of the amount over 17,400 |

| $70,700 | $142,700 | 25% | $9,735 plus 25% of the amount over $70,700 |

| $142,700 | $217,450 | 0.28 | $27,735 plus 25% of the amount over 142,700 |

| $217,450 | $388,350 | 33% | $48,665 plus 33% of the amount over $217,450 |

| $388,350 | No limit | 35% | $105,062 plus 35% of the amount over $388,350 |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation’s Analysis of the National Bureau of Economic Research’s “Internet TAXSIM, Version 9”. | |||

II. Annual Caps on Tax Payments Supporting the Social Security Program

The other major reason that the tax reduction varies by income is that there is an annual cap on the portion of federal payroll tax payments that support the Social Security program (which, in combination with tax payments to support Medicare, is known as the FICA tax). Under the Social Security portion of the payroll tax, both employees and employers pay 6.2% of wages (for a total of 12.4%) to support the program. However, the 12.4% employee-employer assessment to support Social Security is capped; the assessment is only collected on wages up to an annual per employee earnings limit. The limit in 2012 was $110,100 per worker.8 Therefore, an employer with wages of $150,000 in 2012 would pay 6.2% towards FICA only on $110,100 of the employees’ wages.9 The annual cap means that for workers with wages lower than the annual limit, the exclusion of employer and employee premium payments from the Social Security portion of FICA results in a tax reduction of $0.124 for each dollar excluded. Workers with wages above the annual limit, however, have already stopped paying the Social Security portion of FICA for wages earned beyond the annual limit, so additional income shielded by the tax exclusion would not be subject to the 12.4% anyways. It is important to note that FICA is assessed based upon a workers income and not on a households combined income.

Whereas the progressive tax rates mean that wealthier households receive a higher-valued reduction in their tax bill, the Social Security limit works the other way providing relief only to households with incomes less than the $110,100 limit.

The Medicare payroll tax is structured differently from that of Social Security. The Medicare tax is uncapped; every dollar in taxable wages is subject to it. Like the Social Security tax, both employers and employees contribute a fixed percentage, which in this case is 1.45% of wages or (2.9% in total), to support Medicare. The combined employee and employer portions of the Social Security and Medicare payroll tax for workers below the Social Security earnings limit is 15.3% of taxable wages.

Demonstrating Varying Impacts of Tax Exclusion by Family Income

The amount of tax reduced by the health insurance tax exclusion varies with family income. (See Appendix A for a description of how tax reduction is calculated.) For the following examples we assumed the characteristics below of a family, relating to their tax liability:

- The family has four members, two of which are working spouses and two are dependent children;

- The family has only wage income;10

- The wages after all insurance contributions are equally divided between the spouses;

- One spouse receives a family health insurance policy valued at $12,500 through his or her employer;

- The employer contributes $10,000 toward the cost of the policy and the family contribution of $2,500 is paid through a Section 125 plan; the family does not itemize deductions. This means that the household takes the standard tax deduction of $11,900 for a couple filing jointly in 2012.

- The family resides in California, which has a progressive income tax schedule.

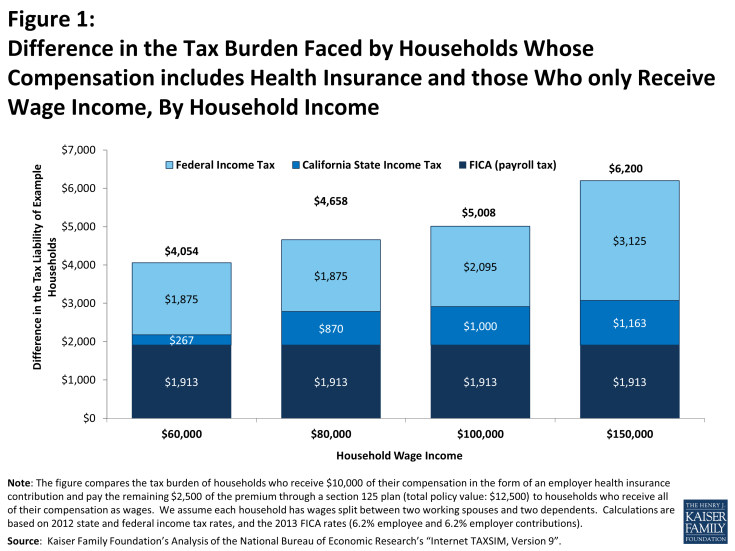

Figure 1 shows the difference in tax reductions for households whose compensation includes ESI versus households without ESI coverage. For this figure, we look at sample families with annual wages at $60,000, $80,000, $100,000, and $150,000.11 Each bar in the figure represents the difference in the tax burden of a household with an employer plan subtracted by the tax liability of a family without coverage. For example, a household with a wage income of $60,000 that receives employer healthcare coverage pays $4,054 less in total taxes than a household whose compensation does not include coverage. The income tax reductions and the total tax reduction grow steadily with income, reflecting the progressive income taxes at the federal and state level. The FICA reduction is the same in each case, reflecting how the tax is the same percentage for each of the example households, despite the variation in income levels. In these examples, while family income exceeded the threshold for Social Security taxes for the highest family income categories, since we assumed the family has two wage earners making equal amounts, no individual worker’s salary exceeded the annual cap. The total tax reduction varies from over $4,000 at the lower end of the income range presented to over $6,000 at the higher end, or between 32% and 50% of the total premium value.

Figure 1: Difference in the Tax Burden Faced by Households Whose Compensation includes Health Insurance and those Who only Receive Wage Income, By Household Income

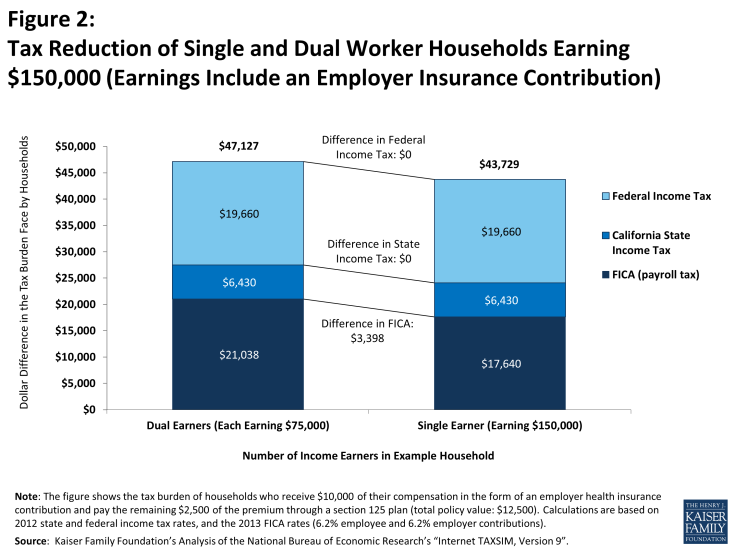

Figure 2 demonstrates the impact of the annual Social Security earnings limit for FICA tax liability. Two families both earning $150,000 in wages and receiving a $12,500 health insurance policy through an employer face different tax burdens. As in the previous example, the employer makes a $10,000 contribution and the employee contributes $2,500 through a Section 125 plan. The two workers family has two earners both under the annual Social Security earnings limit ($110,100 in 2012). On the other hand, the single worker family stops paying the Social Security portion of FICA once his or her wages reaches the limit,12 so the tax exclusion for health insurance does not reduce the FICA contribution that that worker makes for the Social Security portion of FICA. The worker in the two earner family is taxed for the full FICA assessment for each additional dollar of earnings. The tax exclusion for the one earner family is over $3,000 larger than the exclusion for two earner family because of the cap for the Social Security portion even though their total earnings ($150,000) exceeds the cap.

Figure 2: Tax Reduction of Single and Dual Worker Households Earning $150,000 (Earnings Include an Employer Insurance Contribution)

These examples show that the federal tax exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance results in substantial levels of tax reduction for families at different earnings levels and that the total tax reduction increases with family earnings. The primary reason that the tax reduction increases with family earnings is due to progressive income tax rates – the marginal tax rate for each dollar of income tends to be higher as income grows (until family income reaches the top federal and state income tax rates).

Of course, actual families have much more complicated earnings and income situations than shown here. For example, some families will have itemized deductions which will lower their taxable income and may lower their marginal tax rate, effectively lowering the amount of tax reduced by the exclusion. Conversely, families may have other types of income, such as interest income, that would increase their total taxable income, potentially raising their marginal tax rate and the amount of tax reduced by the exclusion. The situation can be even more complex for lower-income families, because employer contributions for ESI are not considered as income when considering eligibility for programs such as the earned income tax credit (EITC) or the child care tax credit. While there are many potential scenarios that could be provided with differing family circumstances and differing tax reduction impacts, the important point is that, because health insurance is costly, the decision not to tax employer and employee premium payments often has a significant impact on family tax liability. Given that higher-income households are more likely to be offered coverage and more likely to receive a larger employer contribution, the effects of the tax subsidy are more dispersed by income when examining the country as a whole. The tax preference for employer coverage may in part explain why health insurance continues to be an important recruiting tool for employers, and some employees continue to expect coverage from their employer.

II. Non-Group Coverage

Unless they are eligible for public coverage, people who are not offered health insurance from an employer must seek individual health insurance, sometimes known as non-group coverage. The ACA instituted significant reforms to the non-group market, including establishing state and federal marketplaces where individuals can shop and purchase coverage. Starting in 2014, qualifying households are able to receive premium tax credits to purchase discounted coverage on the exchanges. In addition to tax credits, existing law allows households to deduct certain medical expenses from their taxes, including the cost of health insurance premiums. The tax benefits for non-group coverage are structured progressively, with greater relief for lower-income households. This section first examines the value of tax-deduction for non-group plans before looking at examples of households who receive the tax-deduction and a premium tax credit.

Federal Tax Deduction for Medical Expenses

Families that itemize their deductions can deduct the portion of their medical expenses, including health insurance premiums that exceed 10% of their adjusted gross income.1 A wide variety of medical expenses qualify for this deduction including: out-of-pocket expenses, such as acupuncture, ambulance services, and smoking cessation programs, as well as insurance premiums. So, even if a family purchases a health insurance plan with a low premium, they may still claim the deduction if they incur other health care costs exceeding the 10% threshold. The ACA increased the income threshold at which households could claim medical expenses in two ways. First, the threshold was increased for non-elderly families, from 7.5% to 10% of income. For example, a household earning $100,000 can now deduct expenses greater than $10,000 a year as opposed to $7,500. Secondly, elderly families also have to meet the 10% threshold when their income is high enough to invoke the alternative minimum tax.

There are two important limitations associated with the medical expense deduction. The first is that it is only available to families who itemize their deductions. Families generally itemize their deductions when the amount of itemized deductions exceeds the standard deduction otherwise available to tax filers. In 2012 the standard deduction amounts were $5,950 for people who were single or married couples filing separate tax returns, $11,900 for married couples filing a joint tax return (or certain widowers with dependent children), and $8,700 for people filing as head of a household.2 Federal tax law permits itemized deductions for a number of different expenses, including medical and dental expenses, certain state and local taxes paid by the family, real estate and property taxes, interest on a home mortgage loan (and other home mortgage expenses), charitable gifts, casualty and theft losses, and certain business expenses. Families that pay mortgage interest, for example, are likely to benefit from itemizing their deductions, and may then be able to deduct a portion of their non-group health insurance premiums as well. The percentage of households who itemize deductions increases with a household’s income; 22% of households with adjusted income between $20,000 and $50,000 itemize their deductions, compared to 55% of households between $50,000 and $100,000, and 84% of households between $100,000 and $200,000.3

The second limitation is that the medical and dental expense deduction is limited to expenses that exceed 10% of adjusted gross income for non-elderly households. If the only medical expense for a family earning $80,000 was a $12,500 family non-group premium, the family could deduct $4,500 of the premium ($12,500 premium minus 10% of the $80,000 income, or $8,000). The amount of the tax deduction would depend on the family’s marginal income tax rate, which would be largely determined by the amount of their other deductions. Note, a family with $80,000 of adjusted gross income who opts for a lower, non-group premium of $8,000 could not take a deduction in this case, because 10% of their adjusted gross income ($8,000) is equivalent to the premium amount. Families with higher incomes are unlikely to be able to take a deduction for their non-group premiums unless they have significant amounts of other medical expenses, or purchase an expensive policy.

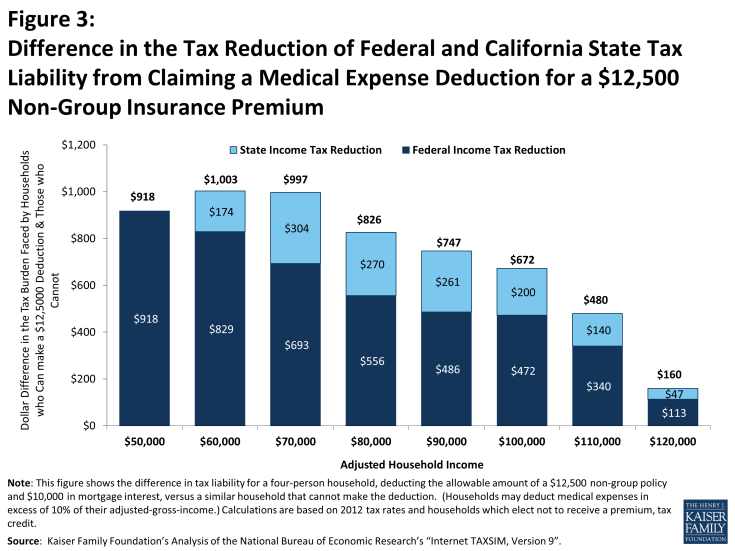

Figure 3 shows examples of how the medical expense deduction could work for families with different incomes. The example shows families with different levels of wage income and no other income, similar to the examples above, but these families do not have ESI and do not receive tax credits authorized under the ACA. The families are assumed to purchase a non-group health insurance policy with an annual premium of $12,500, and have no other medical or dental expenses to deduct. To ensure that the families have sufficient deductions to itemize, we also assume that the families pay $10,000 in mortgage interest and take deductions for state taxes (the amounts deducted vary with income and are calculated through the TAXSIM model). We are comparing families who can take the tax deduction versus similarly-earning families who do not. So, for families who can take the deduction, we first deduct the portion of the $12,500 premium that exceeds 10% of their adjusted gross income and then use the model to calculate federal and state income tax liabilities. The differences in tax reductions for these families are shown in the Figure 3.4 A family with an income of $60,000 will owe $1,003 less in taxes than a family earning the same income who does not take the deduction. A family with $100,000 of income will only save $672 in taxes compared to its counterpart.

Figure 3: Difference in the Tax Reduction of Federal and California State Tax Liability from Claiming a Medical Expense Deduction for a $12,500 Non-Group Insurance Premium

The tax deduction has a smaller impact for higher income households, because they can deduct a smaller portion of their medical expenses. In our example, the family with $60,000 of income can deducted $6,500 of the premium while the household earning $100,000 can only deduct $2,500. Partially offsetting the impact of falling deduction amounts is that the marginal tax rates increase with income, so families at higher incomes save a larger share of the smaller amount that they can deduct (see Table 3). For example, the family at $50,000 can deduct $7,500, but because their tax rate is relatively low, their federal savings are only about 15% of their deduction. In contrast, the family at $100,000 can deduct only $2,500, but their federal tax reduction is about 25% of the amount deducted. It is important to note that this medical expense deduction is an income tax deduction which, unlike the tax exclusion for ESI discussed above, works only to reduce income tax liability and not the amount of FICA taxes paid.

Premium Tax Credits for Non-Group Coverage

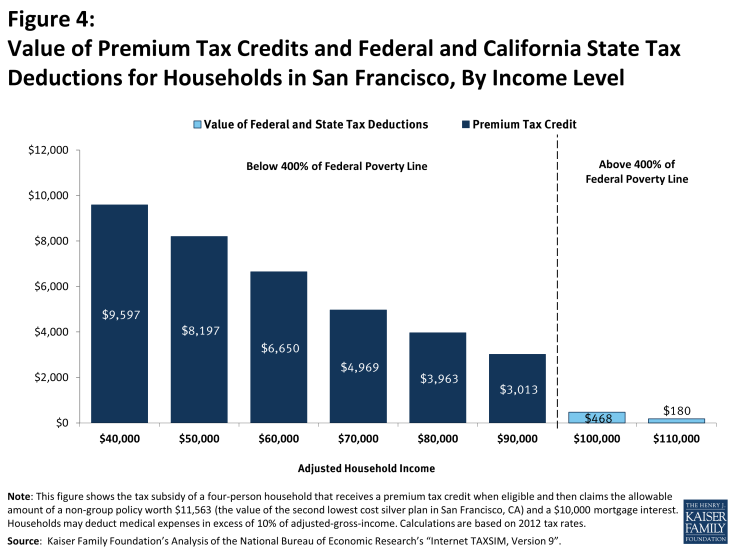

The establishment of tax credits for non-group coverage has meaningfully changed the tax incentives for households purchasing non-group coverage. Starting in 2014, low-income households without an offer of employer coverage and incomes between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level will be eligible for tax credits for qualifying non-group coverage on health insurance exchanges. Tax credits will be assessed on a sliding scale, with higher income families’ receiving a smaller credit than households with more modest incomes. Households between 100% and 250% of the federal poverty line may qualify for additional tax credits designed to lower the cost sharing required for the plan they choose. Premium subsidies are structured so households with incomes beneath 400% of poverty are not required to contribute more than 9.5% of their income to purchase a silver plan (a plan that covers on average 70% of the cost of health benefits)5. This provision means that fewer households will be able to take advantage of the tax deduction of medical expenses without incurring out-of-pocket expenses. Families may elect to purchase a higher cost, gold or platinum plan, which could increase their premium contribution above the 10% threshold. Figure 4 looks at the premium tax credits and tax deductions available to example households in San Francisco.

Figure 4: Value of Premium Tax Credits and Federal and California State Tax Deductions for Households in San Francisco, By Income Level

San Francisco is a relatively high cost area. The second lowest-cost silver plan, which covers roughly 70% of an average enrollees’ expenses, is valued at $11,563 for a non-smoking couple with two children. Households earning between $40,000 and $90,000 in income qualify for subsidies ranging from $9,597 to $3,013 a year. The tax credits lowered the medical spending for the example households with incomes between $40,000 and $90,000 below the 10% threshold required to deduct expenses. For example, a household with an income of $40,000, premium costs of $11,563, and a tax credit of $9,597 has medical expenditures equivalent to 4.9% of the total income ($1,966 in medical expenses, assuming no other medical expenses are made). The premium tax credits available on health insurance exchange provide a much higher tax subsidy to households than they would have been able to receive before 2014. An example household with an income of $60,000 who purchase non-group coverage without a premium tax credit could receive a $1,003 worth of tax deductions (figure 3) whereas the example household who purchase a plan on the health insurance exchange can receive a tax credit of $6,650 (figure 4).

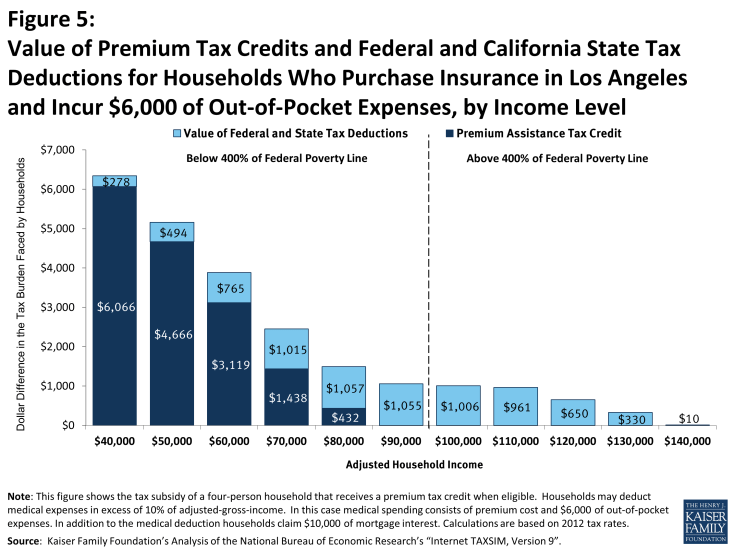

Figure 5: Value of Premium Tax Credits and Federal and California State Tax Deductions for Households Who Purchase Insurance in Los Angeles and Incur $6,000 of Out-of-Pocket Expenses, by Income Level

Households making between $100,000 and $110,000 dollars a year earn too much to qualify for premium assistance tax credits but have incomes low enough that at least part of their premium can be deducted.6 Households earning $120,000 or more a year are not eligible to deduct any medical expense unless they incur other out-of-pocket medical expenses.

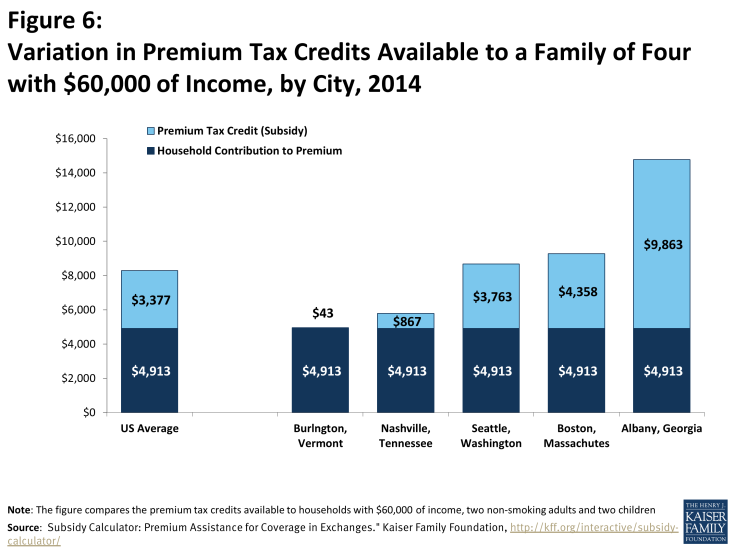

The tax credits available on the health insurance exchange vary in important ways other than income. In many parts of the country, health insurance premiums are less than in San Francisco; in cases in which the premium is less than $10,000, no household will be able to deduct any of the cost of the premium unless they have other out-of-pocket expenses. Since premium tax credits limit the amount of a household’s income they are required to spend on coverage, households in areas with higher premiums receive a larger tax credit. Figure 6 shows examples of regional variation for the same four person family earning $60,000 dollars in different cities.

Figure 6: Variation in Premium Tax Credits Available to a Family of Four with $60,000 of Income, by City, 2014

Examples with Premium Tax Credits And Medical Deductions

Many non-group plans require considerable cost-sharing from enrollees. Households who incur out-of-pocket expenses may receive both a premium tax credit and deduct medical expenses. For example, we calculated the tax burden of households who purchased coverage in Los Angeles and have $6,000 dollars of out-of-pocket medical expenses, such as deductibles or copayments.7 The second lowest cost silver premium is less expensive than in San Francisco, costing a non-smoking couple with two kids $8,032. Table 4, illustrates the amount that households are able to deduct by income level; for example the household with a $100,000 of income can deduct 4,032, which accounts for the value of their premium ($8,032) plus the value of their out of pocket spending ($6,000). The example households with incomes between $40,000 and $80,000 qualified for the premium assistance tax credits on the health insurance exchanges. While the example household with $90,000 earns less than 400% of the federal poverty line, the total cost of the premium does not exceed 9.5% of their household income and they therefore do not qualify for a premium assistance tax credit. All of the example households below 400% of poverty are able to deduct medical expenses ranging from $3,965 to $5,032; in each case, these households’ contributions to the insurance premium in addition to their out-of-pocket expenses exceeded 10% of their income. While households between $90,000 and $140,000 dollars are not eligible for a premium assistance tax credit they are able to deduct the portion of their medical spending that exceeded 10% of their income.

| Table 4 | ||||

| Individual Premium Contribution (value of premium – premium assistance tax credit) |

Assumed Out-of-Pocket Spending | Medical Spending (premium contribution + out-of-pocket spending) | Deductible Medical Spending (Medical Spending -10% of Income) |

|

| $40,000 | 1,965 | 6,000 | 7,965 | 3,965 |

| $50,000 | 3,365 | 6,000 | 9,365 | 4,365 |

| $60,000 | 4,913 | 6,000 | 10,913 | 4,913 |

| $70,000 | 6,594 | 6,000 | 12,594 | 5,594 |

| $80,000 | 7,600 | 6,000 | 13,600 | 5,600 |

| $90,000 | 8,032 | 6,000 | 14,032 | 5,032 |

| $100,000 | 8,032 | 6,000 | 14,032 | 4,032 |

| $110,000 | 8,032 | 6,000 | 14,032 | 3,032 |

| $120,000 | 8,032 | 6,000 | 14,032 | 2,032 |

| $130,000 | 8,032 | 6,000 | 14,032 | 1,032 |

| $140,000 | 8,032 | 6,000 | 14,032 | 32 |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, “Analysis of Subsidy Calculator: Premium Assistance for Coverage in Exchanges.” Kaiser Family Foundation, n.d. Web. 21 Mar. 2014. https://www.kff.org/interactive/subsidy-calculator/. | ||||

Given the high cost sharing in plans being offered on the exchanges, many households receiving premium tax credits will face considerable out-of-pocket spending if they use services. The medical spending deduction will continue to provide tax relief to these households. The combination of premium tax credits and the medical deduction provide a larger tax subsidy to lower income households’ families. The example households who receive smaller premium tax credits (those with incomes between 300% and 400% of federal poverty) received the most benefit from the medical deduction.

III. Special Tax Deduction for Health Insurance Premiums for the Self-Employed

People who are self-employed often look to the non-group market for health insurance. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that one-in-nine workers, or 15.3 million people, were self-employed in 2009.1 Starting in 2014, these households are able to access health care coverage and premium tax credits through the health insurance exchanges. In addition to premium tax credits, self-employed households can deduct the full cost of qualifying medical expenses.

Self-employed individuals are subject to federal income tax as well as self-employment tax, which is the equivalent to the FICA payroll taxes.2 A special tax provision permits the self-employed to take a deduction when calculating their income tax for the amount paid for health insurance for themselves and their spouse or dependents.3 To qualify for the deduction, health insurance must be established under the self-employed person’s business. This deduction, however, has several limitations. First, the deduction may not be taken if the self-employed individual, or his/her spouse, was eligible for subsidized coverage offered by an employer. For example, if a self-employed individual was eligible for health benefits offered by the spouse’s company from January through March but the self-employed individual was paying premiums for an individual plan, those premiums would not be eligible for the deduction. A second limitation is that the amount deducted cannot exceed the net profit and other earned income from the business under which the health insurance plan is established. For example, a person with a small amount of self-employment income and additional income from other sources cannot deduct the full amount of his or her health insurance premiums if the premiums exceed the net profit of the business. A third limitation is that self-employment health insurance deductions reduce income for income tax purposes only, and may not be deducted when calculating the net earnings subject to the self-employment tax.

Self-employed households have the same income eligibility requirements for premium tax credits as households with wage income. Unlike individuals in the non-group market, self-employed households are able to deduct the full value of their qualified medical spending pending that their business generates sufficient net profit.

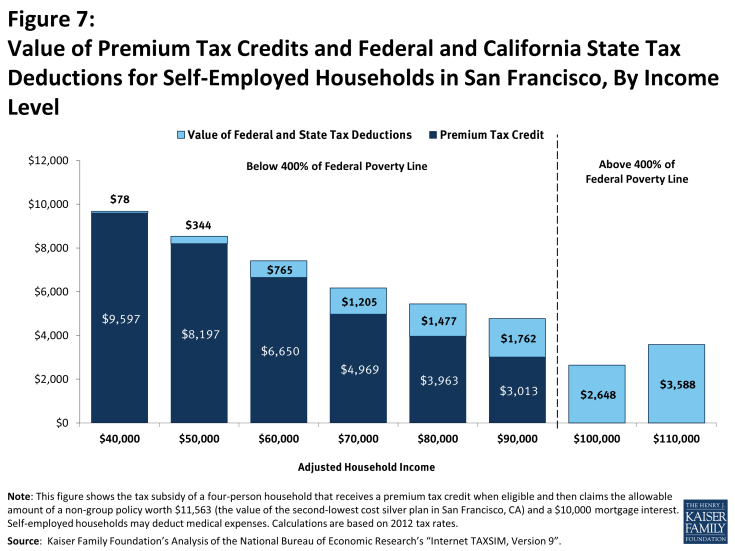

Figures 7 shows examples of the tax reductions for self-employed households enrolled in the second lowest-cost plan in San Francisco. The scenarios are the same as those assumed under Figure 4, except that the families deduct the full amount of their health insurance premium.4 The reduction amounts shown are calculated by computing each family’s taxes with and without a deduction for health insurance. The example households below $100,000 benefit from both the premium tax credit and the self-employed health insurance deduction. Similar to the dynamics for individuals in the non-group market, the tax deduction is regressive as it rewards wealthier families more; and the premium tax credit is progressive as it provides a higher subsidy for lower income households. The example households at or above $100,000 earn more than 400% of the federal poverty line and therefore pay the full premium cost ($11,563). Self-employed households at all income levels receive a higher tax subsidy than households with wage income, reflecting the fact that those that are self-employed can deduct the full amount of health insurance premiums, while people taking the medical expense deduction can only deduct expenses exceeding 10% of their adjusted gross income. Another interesting component of the tax burden faced by self-employed households is that they are unable to deduct health insurance spending from their self-employed tax liability. Because workers who receive an employer sponsored plan are not assessed FICA taxes on the value of their plan, employed-workers pay a smaller tax burden than similarly situated self-employed workers.

Figure 7: Value of Premium Tax Credits and Federal and California State Tax Deductions for Self-Employed Households in San Francisco, By Income Level

IV. Conclusion

The examples show that the availability and amount of tax subsidies for health insurance vary by a number of factors, including the amount and types of income that a person or family may have and whether they receive coverage through work. Importantly, the different tax subsidies relate to income in different ways. The exclusion of employer and employee contributions from income taxes favor higher income families more than lower income families because these families face higher marginal tax. The accompanying exclusion from FICA payroll taxes behaves differently: it is the same for everyone with the same earnings until the earnings reach the Social Security limit. In contrast, the new tax credit for nongroup coverage is structured to provide more benefit to lower income families, and phases out as income rises, with no benefit for families with incomes above 400 percent of the federal poverty line. Families with higher incomes purchasing nongroup coverage can only receive tax assistance if they have high medical expenses (including their health insurance premiums) relative to their incomes.

These different tax subsidies can lead to quite different results for similar families receiving similar coverage, but through different sources. For example, a low-income family that purchases nongroup coverage in a public marketplace may be eligible for a premium tax credit that pays for most of their premium, but if that same family received the same coverage through work, the tax subsidy would equal only a small percentage of the premium. At the other end of the spectrum, a higher income person who receives coverage through work may receive a tax subsidy of over 40 percent of the premium, but may receive no assistance if they purchased an identical policy in the nongroup market.

The reason for the widely different results is that we have several different tax subsidies that were enacted at different times with different goals. There is no clear policy relating the availability of assistance to income or resources, which means that families with similar economic needs are treated quite differently depending on the source of their coverage.

This brief is an update of “Tax Subsidies for Health Insurance” published in June 2008 by Gary Claxton of the Kaiser Family Foundation and Paul Jacobs who formerly worked in that division.

Key Terms

Premium assistance tax credits. Tax-credits available to individuals without an offer of employer coverage and incomes between 100% and 400% of the Federal Poverty Level. Individuals can use premium assistance tax credits to purchase private coverage on health insurance marketplaces. Information on eligibility and value of premium assistance tax credits is available at: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/faq/health-reform-frequently-asked-questions/

Pre-tax income. The term “pre-tax” is used to describe compensation that an employee receives from an employer that is not subject to income tax or FICA payroll taxes. Normally, if an employee earns a dollar in wages, the employee must pay federal and state taxes on that dollar. Federal law provides that certain types of compensation received by an employee, including employer contributions to health insurance, are not subject to federal income tax or FICA taxes. Federal law also permits employers to establish arrangements that permit employees to pay their share of health insurance premiums with income that is not subject to income or payroll taxes.

Adjusted gross income (AGI). AGI is defined as: “taxable income from all sources . . . minus specific deductions such as education expenses, the IRA deduction, student loan interest deduction, tuition and fees deduction, Archer MSA deduction, moving expenses, one-half of self-employment tax, self-employed health insurance deduction, self-employed SEP, SIMPLE, and qualified plans, penalty on early withdrawal of savings, and alimony paid by [the tax payer].” (Available online at: http://www.irs.gov/app/freeFile/html/moreInfo/more_info_agi.html.)

Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI). MAGI is a households income when determining eligibility for premium assistance tax credit. In addition to AGI, MAGI includes non-taxable Social Security benefits, tax-exempt interest, and foreign income. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/faq/health-reform-frequently-asked-questions/#tag-magi

Deduction. A deduction is an amount that a person can subtract from their adjusted gross income when calculating the amount of tax that they owe.

Standard deduction. The basic standard deduction is a specified dollar amount that taxpayers can deduct from their income in determining their taxes. (See Table 7, available online at http://www.irs.gov/publications/p501/ar02.html.) The amount varies with the filing status (e.g., single, married filing jointly, etc.) of the taxpayer. A taxpayer can take the standard deduction or can take deductions related to specified expenses (referred to as itemized deductions).

Credit. A tax credit is an amount that a person can subtract from the amount of income tax that they owe. If a tax credit is refundable, the taxpayer can receive a payment from the government to the extent that the amount of the credit is greater than the amount of tax that the individual would otherwise owe.

Personal exemption. A personal exemption is an amount that a taxpayer can deduct for themselves and their dependents when calculating taxable income.

FICA. The Federal Insurance Contributions Act requires individuals and employers to pay a tax on compensation to fund Social Security and Part A of Medicare. Both the employer and the employee pay 6.2% (12.4% combined) on earnings up to the Social Security wage base ($117,000 in 2014, 113,700 in 2013 and 110,100 in 2012) for the Social Security Program. Both the employer and the employee pay 1.45% (2.9% combined) of all wages for Part A of Medicare. The total combined FICA contribution on a dollar of earnings (for 2012) is 15.3% for wages up to $110,000 and 2.9% for wages above $110,000.

Medical expense deduction. Federal law permits taxpayers to deduct the portion of medical expenses, including premiums for health insurance that exceeds 10% of adjusted gross income as an itemized deduction. (See IRS Publication 502 for more information, available online at: http://www.irs.gov/publications/p502/ar02.html.)

Appendix

Appendix A. Calculation of Tax Reduction for ESI Tax Exclusion Examples

The tax reductions shown in this paper were calculated using Taxsim Version 9, which is a program that permits users to calculate federal and state taxes for individuals and families with various characteristics. For this exercise we calculated each family’s tax liability under current law and then recalculated it assuming that the family received the amount of the employer contribution for health insurance as additional wage income. The differences in the federal and state income tax liability and the FICA tax liability are the reduction amounts shown in the figures. For example, one of the sample families has $60,000 in wage income and a $10,000 health insurance contribution from their employer. The family contributes their share of the $12,500 premium, or $2,500, through a Section 125 plan. For the comparison, we first reduced the family’s wage income to $48,500, reflecting that the family is able to pay their $2,500 share of the premium with pre-tax income, and then calculated the federal, state, and FICA taxes. We then recalculated the family’s tax liability assuming wage income of $60,000 ($50,000 of wage income, all of it subject to tax, plus $10,000 of income equal to the employer’s contribution to health insurance). The tax liability differences between these two scenarios are the tax reduction amounts shown in the figures.

Endnotes

Introduction

"Options for Reducing The Deficit: 2014 TO 2023." Congressional Budget Office, Nov. 2013. Web. 21 Mar. 2014. < http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/44715-OptionsForReducingDeficit-3.pdf. See Health Revenues - Option 15, page 243

"Letter to the Honorable John Boehner Providing an Estimate for H.R. 6079, the Repeal of Obamacare Act." Congressional Budget Office, July 2012. Web. 21 Mar. 2014. http://www.cbo.gov/publication/43471.

Lowry, Sean. "Itemized Tax Deductions for Individuals: Data Analysis." Congressional Research Service, Feb. 2014. Web. 21 Mar. 2014. https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43012.pdf.

"Internet TAXSIM Version 9.2." National Bureau of Economic Research. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Mar. 2014. http://users.nber.org/~taxsim/taxsim-calc9/index.html.

Subsidy Calculator: Premium Assistance for Coverage in Exchanges." Kaiser Family Foundation, n.d. Web. 21 Mar. 2014. https://www.kff.org/interactive/subsidy-calculator/.

Issue Brief

I. Federal and State Tax Exclusions for ESI

See 12 United States Code Chapter 21. In 2012 the federal government temporarily reduced the employee social security contribution from 6.2% to 4.2%. In 2013 Congress allowed this tax relief to expire. The results of the tax simulation model used here are adjusted to account for the 2014 employer social security rate.

Although employers pay one-half of the FICA tax amount, economists generally assume that the incidence of the tax falls on employees and not on employers (with an exception for employees earning the minimum wage and subject to the FICA Social Security earnings limit discussed below). Because employers know that they will have to pay a payroll tax of $.0765 for each dollar they pay to an employee, it is assumed that the employer will adjust the employee's pay downward to account for that expenditure. In other words, if the FICA tax did not exist, it is assumed that the employers would pay employees 7.65% more.

United States. US Code. 26 U.S. Code § 125 - Cafeteria Plans. n.d. Web. 03 Apr. 2014. http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/125.

"Employer Health Benefits Survey 2012." Kaiser Family Foundation, Sept. 2012. Web. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/8345-employer-health-benefits-annual-survey-section-14-0912.pdf. See exhibit 14.3 on page 203.

Note: Amounts may not sum to totals due to rounding effects.

Most states have an income tax. For more information on the rates in different states see: "State Individual Income Taxes." State Comparisons. Federation of Tax Administrators, n.d. Web. 03 Apr. 2014. http://www.taxadmin.org/fta/rate/tax_stru.html.

Taxable income means the amount of income that a taxpayer has after deductions and exemptions.

"OASDI and SSI Program Rates & Limits, 2014." U.S. Social Security Administration, n.d. Web. 23 Mar. 2014. http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/quickfacts/prog_highlights/RatesLimits2014.html. The 2014 maximum table earning was 117,000.

Between 2010 and 2012 the payroll tax for employees was reduced to 4.2%. "Payroll Tax Cut to Boost Take-Home Pay for Most Workers."2010/ IRS, n.d. Web. http://www.irs.gov/uac/Payroll-Tax-Cut-to-Boost-Take-Home-Pay-for-Most-Workers%3B-New-Withholding-Details-Now-Available-on-IRS.gov.

The effect of the exclusion from income tax operates based on total family taxable income, while the effect of the exclusion from payroll taxes operates only on earnings. For simplicity, we assumed that families have only wage income. For families with a mix of wage and other sources of income, their tax rates would vary, which would change the tax liabilities we show.

These are the wage amounts before the $2,500 contribution through the Section 125 plan, which has the effect of reducing adjusted gross income by $2,500.

"Publication 15: Employer’s Tax Guide." Internal Revenue Service, n.d. Web. 23 Mar. 2014. http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-prior/p15--2012.pdf.

II. Non-Group Coverage

Families in which either the head of household or his/her spouse is 65 or older can deduct medical expenses in excess of 7.5% of their adjusted income.

2012 Form 1040. IRS. http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-prior/f1040--2012.pdf

Lowry, Sean. "Itemized Tax Deduction for Individual Data Analysis". Congressional Research Service. February 12, 2014. https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43012.pdf

We note that the comparisons shown in Figure 3 were created to allow reasonable comparisons across the income scale, but are probably not very realistic in some regards. It is unlikely, for example, that families at these different income levels would choose to buy the same level of policy, or that many families with $40,000 of income could afford to pay for a mortgage with $10,000 of interest and for a health insurance policy costing $12,500. It is also unlikely that families with these different incomes would have the same mortgage interest.

For more information on the health premium tax credits see: "Explaining Health Care Reform: Questions About Health Insurance Subsidies." Kaiser Family Foundation, n.d. Web. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/7962-02.pdf.

As in Figure 3, we assumed a household had two income earners and a 10,000 mortgage interest deduction.

The Affordable Care Act limits the out of pocket spending on essential benefits to $6,350 for an individual plan and $12,700 for a family plan. Households may incur additional expenses in many ways including spending on non-covered services and going out of network.

III. Special Tax Deduction for Health Insurance Premiums for the Self-Employed

Hipple, Steven. "Self-employment in the United States." Bureau of Labor Statistics, n.d. Web. 12 May 2014. http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2010/09/art2full.pdf

The self-employment tax is the equivalent of the Social Security and Medicare taxes paid by workers. However, instead of the employee and the employer each paying equal shares of the tax, the self-employed pay the entire 15.3% payroll tax themselves. Half of the self-employment tax may be deducted when calculating adjusted gross income.

A self-employed health insurance deduction is available to individuals who are either: (1) self-employed with a net profit reported on Schedule C (Form 1040), Schedule C-EZ (Form 1040), or Schedule F (Form 1040); (2) a partner with net earnings from self-employment reported on Schedule K-1 (Form 1065); or (3) a shareholder owning more than 2% of the stock of an S corporation with wages from the corporation reported on Form W-2. See IRS Publication 535, available online at: www.irs.gov/publications/p535/.

We did not reduce the households modified adjusted gross income to account for qualified health spending. That is to say, the example household with 40,000 dollars of income, has 40,000 dollars of income after all deductions are accounted for. "Modified Adjusted Gross Income under the Affordable Care Act." Center for Labor Research and Education, University of California, Berkeley, n.d. Web. 13 May 2014. http://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/healthcare/MAGI_summary13.pdf.