Olmstead’s Role in Community Integration for People with Disabilities Under Medicaid: 15 Years After the Supreme Court’s Olmstead Decision

The Olmstead Case

The Plaintiffs

The Olmstead case was brought by Lois Curtis and Elaine Wilson, two women with cognitive and mental health disabilities who were institutionalized in Georgia.1 Ms. Curtis had first been institutionalized at age 13.2 In 1992, she was again admitted for inpatient psychiatric treatment. Although her treatment team determined in 1993 that her needs could be met in the community, she remained institutionalized and was not discharged to a community-based treatment program until 1996.3 Similarly, Ms. Wilson was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit in 1995. At one point, the hospital proposed discharging her to a homeless shelter, which she successfully challenged. In 1996, Ms. Wilson’s treating doctor determined that she could be served in the community, but she was not discharged from the institution until 1997.4 Both women sued, arguing that the state’s failure to provide community-based services, as recommended by their treating professionals, violated the ADA. While both women were receiving community-based treatment services when the Supreme Court heard their case, the Court recognized that the nature of their disabilities and their treatment history made it likely that they would again experience institutionalization.5

The ADA’s Community Integration Mandate

In Olmstead, the SupremeCourt noted that Congress enacted the ADA to counteract the historical isolation and segregation of people with disabilities. To address this “serious and pervasive social problem,” the ADA “provide[s] a clear and comprehensive national mandate for the elimination of discrimination against individuals with disabilities.”6 Olmstead involves Title II of the ADA, which prohibits disability-based discrimination by state and local governments. Specifically, Title II provides that people with disabilities may not be excluded from participating in, or denied the benefits of, governmental services, programs, or activities.7

The ADA’s implementing regulations contain its community integration mandate, which requires state and local governments to “administer services, programs, and activities in the most integrated setting appropriate” to the needs of people with disabilities.8 The preamble to the regulations explains that such a setting “enables individuals with disabilities to interact with non-disabled persons to the fullest extent possible.”9 The regulations also require state and local governments to make reasonable modifications to policies, practices, and procedures to avoid disability-based discrimination, unless such modifications would fundamentally alter the nature of the service, program or activity.10 These concepts – most integrated setting, reasonable modification, and fundamental alternation – are the fundamental elements used to analyze an Olmstead claim.

The Court’s Decision

In Olmstead, the Supreme Court considered whether people with disabilities must receive services in the community rather than in institutions. Writing for the majority, Justice Ginsburg answered this question with “a qualified yes.”11 The Court found that community-based services must be offered if appropriate, if a person with a disability does not oppose moving from an institution to the community, and if the community placement can be reasonably accommodated, considering the state’s resources and the needs of other people with disabilities.12 Although Olmstead involved plaintiffs with mental disabilities, subsequent guidance confirms that its principles apply to people with all types of disabilities.13

The Olmstead Court concluded that the “[u]justified institutional isolation of persons with disabilities is a form of discrimination.”14 The Court based its conclusion on two judgments made by Congress in enacting the ADA. First, Congress recognized that the “institutional placement of persons who can handle and benefit from community settings perpetuates unwarranted assumptions that persons so isolated are incapable or unworthy of participating in community life.”15 Second, Congress found that “confinement in an institution severely diminishes the everyday life activities of individuals, including family relations, social contacts, work options, economic independence, educational advancement, and cultural enrichment.”16 In enacting the ADA, Congress sought to eliminate disability-based discrimination and promote the integration of people with disabilities in the community.

The Olmstead Court also suggested a standard to determine whether state governments are avoiding disability-based discrimination and complying with the ADA’s community integration mandate. Specifically, the Court observed that if a state “demonstrat[ed] that it had a comprehensive, effectively working plan for placing qualified persons with mental disabilities in less restrictive settings, and a waiting list that moved at a reasonable pace not controlled by the State’s endeavors to keep its institutions fully populated, the reasonable modifications standard would be met.”17

The Intersection of Medicaid and Olmstead

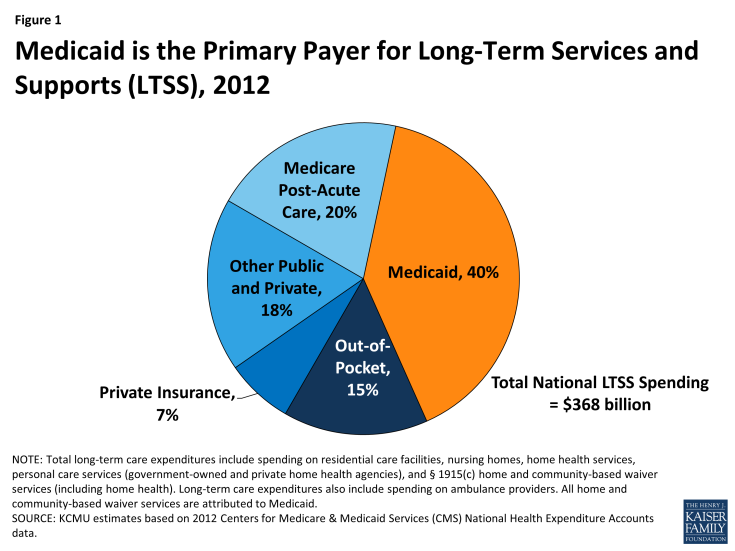

The Olmstead decision focused on the setting in which people with disabilities receive health care and related services. The illegal discrimination in Olmstead arose because “[i]n order to receive needed medical services, persons with mental disabilities must, because of those disabilities, relinquish participation in community life they could enjoy given reasonable accommodations, while persons without mental disabilities can receive the medical services they need without similar sacrifice.”18 While Olmstead does not change or interpret federal Medicaid law, the Medicaid program plays a key role in community integration as the major payer for long-term services and supports (LTSS), including the home and community-based services (HCBS) on which people with disabilities rely to live independently in the community (Figure 1). In 2010, nearly 3.2 million people received Medicaid HCBS, with expenditures totaling $52.7 billion.19

Historically, however, the Medicaid program has had a structural bias toward institutional care because state Medicaid programs must cover nursing facility services, whereas most HCBS are provided at state option.20 While states can choose to offer HCBS as Medicaid state plan benefits, the majority of HCBS are provided through waivers.21 Unlike Medicaid state plan benefits, which must be available to all beneficiaries as medically necessary, waiver enrollment can be capped, resulting in waiting lists when the number of people seeking services exceeds the amount of available funding. In 2012, nearly 524,000 people were on HCBS wavier waiting lists nationally, with the average waiting time exceeding two years; waiting lists vary both across states and within states among waiver target populations.22

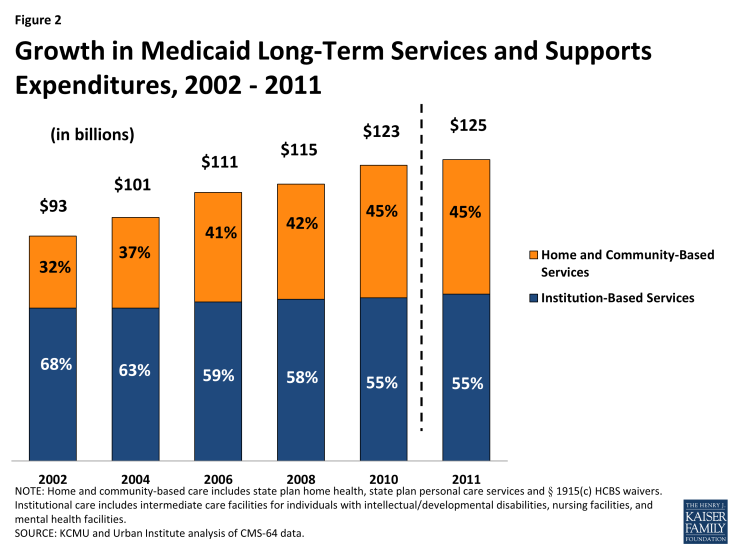

Over the last several decades, states have been working to rebalance their long-term care systems by devoting a greater proportion of spending to HCBS instead of institutional care. These efforts are driven by beneficiary preferences for HCBS, the increased population of seniors and people with disabilities who need HCBS, and the fact that HCBS typically are less expensive than comparable institutional care. In the last 15 years, the Olmstead decision has brought increased focus to state efforts in this area. While the majority of Medicaid LTSS spending still goes toward institutional care, the proportion of Medicaid LTSS spending on HCBS continues to increase relative to spending on institutional services. In FY 2011, HCBS accounted for 45 percent of total Medicaid LTSS spending nationally, up from 32 percent in FY 2002 (Figure 2).

Olmstead Implementation and Enforcement

There have been a number of developments in Olmstead implementation in the last five years, with Medicaid continuing to play a primary role in facilitating and advancing community integration for people with disabilities. In June 2009, President Obama announced the “Year of Community Living” in recognition of the 10th anniversary of the Olmstead decision and the work remaining to be done to eliminate disability-based discrimination. The President’s initiative included over $140 million in funding for independent living centers and new coordination between the Departments of Health and Human Services and Housing and Urban Development to support and promote opportunities for community integration, including increased access to community-based housing through federal housing subsidies.23

At the same time, pursuant to the President’s directive, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) initiated what it describes as an “aggressive effort to enforce” Olmstead and the ADA’s community integration mandate across the country.24 From 2009 to 2012, DOJ’s Civil Rights Division was involved in more than 40 Olmstead cases in 25 states,25 and DOJ’s Olmstead enforcement efforts continue today. DOJ’s Olmstead work takes several forms. It may file a “statement of interest” in an existing lawsuit in which the federal government is not a party but wishes to provide information about the ADA’s legal requirements to the court. DOJ also investigates allegations of Olmstead violations, which can result in a letter of findings and a settlement agreement. DOJ also may initiate litigation to enforce the ADA’s community integration mandate or seek to intervene in an existing case.26 In 2011, DOJ issued a technical assistance guide explaining the rights of people with disabilities and the obligations of state and local governments under the ADA’s community integration mandate.27

The ADA’s community integration mandate also can be enforced by individuals with disabilities, as the Olmstead plaintiffs did with the assistance of legal aid attorneys. Cases can be resolved by negotiating with the state or local governmental entity, without resorting to litigation. Individuals may file an administrative complaint with the Department of Justice or with the Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights (OCR), which is responsible for enforcing state and local government compliance with Olmstead. From August 1, 1999 through September 30, 2010, OCR resolved 850 Olmstead complaints (32 percent after intake and review, 42 percent with corrective action, and 26 percent with no civil rights violations found) and conducted 581 Olmstead investigations, 61 percent of which resulted in corrective action.28 If necessary, individuals also may file a lawsuit seeking relief under the ADA.

Medicaid’s Role in Key Olmstead Implementation Issues

Recent Olmstead cases center around a number of major themes, described below. The cases included are meant to be illustrative and are not an exhaustive list of all Olmstead litigation.29 In each area, Medicaid plays a key role in advancing community integration, as explained below and illustrated by the following short profiles of Medicaid beneficiaries receiving services to support independent living in their communities. While the profiles are not drawn from formal Olmstead cases, they are examples of seniors and younger people with disabilities who benefit from the legacy of Olmstead.

Providing Community Services Instead of Institutionalization

Olmstead cases continue to involve claims similar to those of Lois Curtis and Elaine Wilson, in which people with disabilities seek access to services in the community rather than in institutions. Recent Olmstead cases have involved people with mental illness, intellectual and developmental disabilities, and physical disabilities who are institutionalized.

Court Case Examples

- In 2014, a federal court approved a settlement on behalf of a class of thousands of people with mental illness living in a state-operated psychiatric hospital and nursing facility in New Hampshire. Under the settlement terms, the state agreed to provide expanded community mental health, mobile crisis, and supported employment services and additional scattered site supported housing units.30 DOJ investigated and then intervened in support of the plaintiffs in this case.

- In 2013, an interim settlement agreement was reached on behalf of over 600 people with developmental disabilities living in nursing facilities in Texas. The settlement terms include expanded home and community-based waiver services, person-centered service and transition plans, and an assessment of nursing facility residents to identify those with developmental disabilities. DOJ filed a statement of interest and then intervened in the case on behalf of the plaintiffs.31

- In 2013, DOJ filed a lawsuit in Florida, alleging that children with significant medical needs are unnecessarily institutionalized in nursing facilities when they could be served in the community. The case is currently pending.32

- In 2011, DOJ filed a lawsuit and simultaneous settlement agreement in Delaware on behalf of adults in the state psychiatric hospital. The settlement terms involve the state’s provision of intensive community-based treatment and crisis services, supported employment services, and subsidized housing vouchers to facilitate community transitions. Implementation of the settlement is overseen by an independent court monitor.33

Medicaid’s Role in Deinstitutionalization

Medicaid plays a notable role in deinstitutionalization cases because, as noted above, it is the major source of financing for LTSS, including the HCBS that support people with disabilities in independent community living (Figure 1). In addition to long-standing Medicaid HCBS authorities, such as home health services, personal care services, and § 1915(c) waiver services, Congress created the Money Follows the Person (MFP) demonstration grant program, which provides enhanced federal funding for Medicaid services for beneficiaries who transition from institutions to the community.34 The Affordable Care Act (ACA) extended MFP and also establishes two new Medicaid authorities, Community First Choice attendant services and supports and the Balancing Incentive Program, both of which offer states enhanced federal funding and new options to expand HCBS as they continue efforts to transition people with disabilities from institutional to community-based settings.35

Medicaid Supports Senior’s Move from Nursing Facility to Community Housing

Medicaid Supports Senior’s Move from Nursing Facility to Community Housing

Wanda, age 78

Tulsa, Oklahoma

Wanda was raised in California during the Great Depression and later moved to Oklahoma, where she helped to run her family’s farm. She worked past age 65, but had to retire when she needed hip surgery. Wanda also has degenerative joint disease in her lower back and poor circulation in her lower legs and takes thyroid and blood pressure medications.

Wanda spent nearly two years in a nursing facility after her hip surgery, but Medicaid HCBS made it possible for her to move to a senior living community, where she has resided for more than four years. Medicaid provides the key supports she needs to live at home, including a case manager who coordinates her services, an in-home aide who visits four times a week, home-delivered groceries, and transportation for medical appointments. Wanda says that she enjoys living in a real “community” and is grateful that Medicaid has made it possible for her to live on her own.

Providing Services in the Most Integrated Setting

In addition to deinstitutionalization, some recent Olmstead cases focus more specifically on the type of community setting in which people with disabilities receive services. These cases emphasize the ADA’s requirement that people with disabilities receive services in the most integrated setting, which “enables individuals with disabilities to interact with non-disabled peers to the fullest extent possible.”36

Court Case Examples

- In 2013, DOJ reached a settlement in a New York case on behalf of people with mental illness seeking scattered-site supportive housing in apartments instead of large adult care homes with over 120 residents. The settlement requires that within five years, the state will assess current adult care home residents and transition them to supported housing if appropriate and also provide supported employment and community mental health services, such as care coordination, psychiatric rehabilitation, assistance with medications, home health and personal assistance services, assertive community treatment, and crisis stabilization. The terms of the settlement presume that supported housing is the most appropriate setting for beneficiaries, unless certain exceptions are met.37

- In 2010, a settlement agreement was reached between DOJ and North Carolina, which expands access to community-based supportive housing for thousands of adults with mental illness living in large adult care homes. The settlement requires the provision of community-based mental health treatment and crisis services and supportive employment services for beneficiaries living in their own apartments.38

Medicaid’s Role in Providing Services in the Most Integrated Community Setting

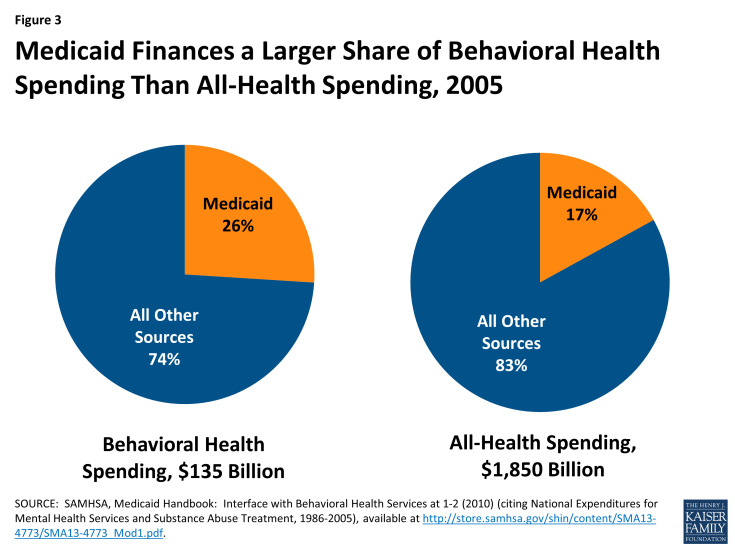

In addition to the long-standing authority to provide home and community-based waiver services, the Medicaid rehabilitative services state plan option also provides states with the flexibility to offer an array of community-based mental health services. Medicaid finances a larger share of behavioral health spending than all-health spending compared to other payers (Figure 3). The Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded the § 1915(i) HCBS state plan option so that states now can provide any HCBS waiver service through state plan authority. Section 1915(i) allows states to target HCBS to specific populations, such as people with mental illness.39 The ACA also established a new health homes state plan option, through which states can receive enhanced federal funding for care coordination services for beneficiaries with chronic conditions, including serious and persistent mental illness.40

Figure 3: Medicaid Finances a Larger Share of Behavioral Health Spending Than All-Health Spending, 2005

Medicaid Enables Man with Developmental Disabilities to Leave a Group Home to Live in His Own Apartment

Medicaid Enables Man with Developmental Disabilities to Leave a Group Home to Live in His Own Apartment

Don, age 41

Owosso, Michigan

Don was born with developmental disabilities. After his mother became too ill to continue caring for him, he lived in a series of group homes, where his sister, Mary, who is his legal guardian, observed that “he wasn’t very happy.” About 10 years ago, Mary was able to help Don put together an array of Medicaid services and supports to help him live safely and independently in his own apartment, which increased his autonomy and enabled him to participate more fully in his community. Don now self-directs his services, which allows him to choose how to allocate his Medicaid dollars among the approved services that he needs to support his living arrangement. Don uses most of his service budget to hire his own caregivers because having caregivers whom he trusts has greatly improved his quality of life.

Preventing Institutionalization for People at Risk

Another theme in recent Olmstead cases is the application of the ADA’s community integration mandate to people with disabilities who are at risk of institutionalization due to a lack of community-based services.

Court Case Examples

- In 2013, the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that a change in eligibility rules that established more restrictive criteria to qualify for Medicaid personal care services in a beneficiary’s own home than in an adult care home created a significant risk of institutionalization. North Carolina was requiring beneficiaries to have a limitation in one out of seven activities of daily living to receive services in an adult care home but two out of five activities of daily living to qualify for services in their own home.41

- In 2012, a case challenging Louisiana’s reduction of the maximum number of personal care services per week that beneficiaries could receive was settled, with the state agreeing to increase its number of Medicaid HCBS waiver slots to expand capacity. DOJ filed a statement of interest supporting the beneficiaries’ claim that the reduction in service hours placed them at risk of institutionalization in violation of Olmstead.42 DOJ filed a statement of interest in support of the beneficiaries.

- In another 2012 case involving personal care services, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals held that across-the-board service reductions could place over 45,000 children with mental illness at serious risk of institutionalization in Washington. The settlement agreement provides for intensive wrap-around services, including care coordination, mobile crisis, and community-based treatment, as well as a process to identify at-risk children.43 DOJ filed a statement of interest on behalf of the beneficiaries.

- In 2011, a federal court in Missouri ruled that Medicaid beneficiaries were at risk of institutionalization as a result of the state’s decision to cover adult diapers as medical supplies for people in institutions but not in the community. DOJ filed a statement of interest supporting the beneficiaries.44

Medicaid’s Role in Providing Services for People at Risk of Institutionalization

Section 1915(i) is unique among the Medicaid HCBS authorities in that it allows states to provide HCBS as a preventive measure for people who do not yet require an institutional level of care. Established by the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, and expanded by the ACA, § 1915(i) permits states to offer HCBS as Medicaid state plan services and requires that beneficiaries meet functional needs-based eligibility criteria that are less stringent than the state’s criteria to qualify for an institutional level of care.45 In addition to the other Medicaid authorities that enable states to provide HCBS to beneficiaries who would otherwise require an institutional level of care, § 1915(i) allows states to provide services proactively to maintain beneficiaries in the community and prevent the need for more costly future services if their medical conditions deteriorated.

Medicaid Provides In-Home Supports That Allow Senior to Avoid Institutionalization

Mary, age 79

Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Mary lives alone in a subsidized apartment building for senior citizens. She has diabetes, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and a history of congestive heart failure and breast cancer. She takes multiple medications and uses oxygen at night and sometimes during the day when she “tries to do too much.” Medicaid provides certified nursing assistant services to help Mary with bathing and dressing, and she is about to start receiving additional Medicaid home and community-based waiver services which she hopes will help with tasks like grocery shopping and cleaning because she can no longer do any heavy work or lifting. She also has difficulty reaching up to get a can down from the top shelf in her kitchen and sometimes needs help making her bed and preparing a meal if she is not feeling well. Mary receives Social Security benefits and food stamps and does not have any extra money to pay for the help she needs after she covers her rent, utilities, and food. She does not want to live in an assisted living or nursing facility and says that receiving Medicaid services will “make a whole lot of difference” in her life.

Replacing Sheltered Workshops with Supported Employment

Another emerging theme among recent Olmstead cases involves greater integration for people with disabilities in community-based employment instead of in segregated settings.

Court Case Examples

- In 2014, DOJ entered into a settlement agreement with Rhode Island on behalf of over 3,000 people with developmental disabilities to resolve DOJ’s findings that the state over-relied on segregated settings such as sheltered workshops at the expense of integrated settings such as supported employment.46

- In 2012, DOJ intervened in an Oregon case in which beneficiaries with developmental disabilities alleged that the state failed to provide them with supported employment services in an integrated setting. At the time, 61 percent of people with developmental disabilities were employed in sheltered workshops, while only 16 percent received supported employment services in the community.47

Medicaid’s Role in Supporting Working People with Disabilities

The Medicaid authorities to provide rehabilitative services and home and community-based services are an important source of supports for working people with disabilities. States elect to provide a range of community behavioral health services under the rehabilitative services option, such as peer support and counseling, basic life and social skills training, community residential services, and supported employment, among others.48 In addition, states can offer HCBS, such as homemaker, home health aide, personal care, and habilitation, through § 1915(c) and/or § 1915(i) to help people with disabilities accomplish the activities of daily living necessary to get ready for the work day. States also can use these authorities to offer supported employment services.

Medicaid Provides Necessary Supports to Enable Man with Disabilities to Work in the Community

Medicaid Provides Necessary Supports to Enable Man with Disabilities to Work in the Community

Mark, age 43

Nashville, Tennessee

Mark has worked as a grocery store courtesy clerk for 12 years and enjoys having a “real job” outside of a sheltered workshop. He has autism and intellectual disabilities. He is very rigid about his daily schedule and will not deviate from his routine. He bathes and dresses himself but needs help with shaving because he will not look into a mirror. When he first started at the grocery store, he received job coaching services, but he has since mastered his work tasks and no longer requires regular on-the-job supports. In addition to his wages, his job provides him with the opportunity for social interaction in the community.

Mark has long been on a Medicaid HCBS waiver waiting list for a community-based residential placement. He has lived with his parents for his entire life, but it is becoming increasingly difficult for his parents to provide his care now that they are getting older and developing their own health issues. Mark’s mother would like him to live in a small group home and to move while she is able to assist with his adjustment during the transition. Receiving Medicaid waiver services for a community-based residential placement would support Mark’s continued employment and provide peace of mind for his aging parents.

Eliminating Disability-Based Discrimination within the Medicaid Program

Another theme emerging from Olmstead cases involves modifying Medicaid rules, such as service hour and/or cost caps, to reasonably accommodate the needs of people with significant disabilities pursuant to the ADA.

Court Case Examples

- In 2010, a Texas federal court ruled that the state Medicaid program’s cost cap on nursing services should be modified to prevent the institutionalization of a man with multiple disabilities. Under Medicaid’s Early, Periodic, Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit for people up to age 21, this man had received 18 to 20 hours of nursing services per day. However, when he aged out of EPSDT, the state applied a cost cap to nursing services for adults that prevented him from receiving enough services to remain in the community.49

- In 2004, the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals held that the ADA required Illinois to waive its cap on private duty nursing hours for adults. In that case, the Medicaid beneficiary seeking services had received 16 hours per day under EPSDT, but qualified for only 5 hours per day as an adult, which was insufficient for him to remain safely at home. The court applied Olmstead and concluded that waiving the service hour cap would not fundamentally alter the state’s Medicaid program because so few people had such extensive care needs. The court also noted that providing HCBS was less expensive than comparable institutional care.50

Medicaid’s Role in Eliminating Disability-Based Discrimination

Cases that grant reasonable modifications to Medicaid policies that would otherwise result in the institutionalization of beneficiaries underscore the fact that states’ obligations to people with disabilities under the ADA are independent of the requirements that states must meet under the Medicaid program. CMS notes that states must administer their Medicaid programs in a way that does not discriminate against people with disabilities in keeping with the ADA. In addition to typically being less expensive and in line with beneficiary preferences, providing community-based services enables states to meet their ADA obligations.

Developing Issues in Olmstead Implementation

While advancements such as those described above have been made, work remains to be done to achieve full community integration for people with disabilities. In these areas, Medicaid continues to offer the means to facilitate solutions that implement the ADA’s integration mandate. Issues to watch as Olmstead implementation proceeds include:

- Whether LTSS spending is rebalanced toward HBCS in a way that affords the opportunity for community integration for people with disabilities. A 2013 U.S. Senate Committee report notes that increased HCBS access for people with developmental disabilities has outpaced that for seniors and people with physical disabilities, and according to CMS, over 200,000 people remaining in nursing facilities in 2012, or nearly 16 percent, are under age 65.51 Through initiatives such as the Balancing Incentive Program, CMS and states are working to develop and expand no wrong door/single entry point systems and core standardized assessments to achieve greater equity among different populations receiving Medicaid HCBS.

- Whether states’ Olmstead plans contribute to continued progress toward community integration. While the Supreme Court suggested that states can use such plans as tools to comply with their ADA obligations, the 2013 Senate Committee report notes that these “planning efforts vary considerably, ranging from simple lists of recommendations to more comprehensive action plans” with many “lack[ing] detailed enforceable benchmarks.”52 The new and expanded Medicaid authorities to provide HCBS, such as MFP, Community First Choice, § 1915(i), and the Balancing Incentive Program, afford states additional options and flexibility to rebalance their LTSS spending which could be incorporated into state Olmstead plans. Exploring ways to streamline the various Medicaid HCBS authorities may facilitate state adoption and expansion of HCBS.

- Whether community-based settings provide the fullest extent of integration possible for people with disabilities, consistent with the ADA. The 2013 U.S. Senate Committee report notes that states are making progress in increasing the number of people receiving HCBS and the amount spent on HCBS, but are not always providing services to people “in their own homes,” even though this is the most integrated setting for virtually all beneficiaries.53 CMS’s recent finalization of regulations that define a “home and community-based setting” for services across Medicaid HCBS authorities presents an opportunity for states, beneficiaries, providers, and other stakeholders to focus on this aspect of community integration.54

- How Olmstead’s principles are integrated into care delivery system reforms. States are increasingly interested in delivery system reforms, such as moving to capitated or managed fee-for-service managed care models, within their Medicaid programs and/or as a way of integrating and coordinating Medicare and Medicaid services for dually eligible beneficiaries. These initiatives are increasingly encompassing people with disabilities and LTSS. CMS’s 2013 guidance specifies that states implementing Medicaid managed LTSS must administer these programs consistent with Olmstead and the ADA’s community integration mandate.55 While these models offer the opportunity for increased access to HCBS, they also could involve potential risks of disrupting established services for the most vulnerable beneficiaries.