Medicaid Enrollment & Spending Growth: FY 2019 & 2020

States reported declines in Medicaid enrollment and modest growth in total Medicaid spending for state fiscal year (FY) 2019 and budgeted for nearly flat enrollment growth but a return to more typical rates of spending growth for FY 2020. These Medicaid changes fall against the backdrop of robust state economies marked by strong revenue growth and low unemployment. This brief analyzes Medicaid enrollment and spending trends for FY 2019 and FY 2020 based on interviews and data provided by state Medicaid directors as part of the 19th annual survey of Medicaid directors in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The methodology used to calculate enrollment and spending growth as well as additional information about Medicaid financing can be found at the end of the brief. Key findings are described below and in a companion report.

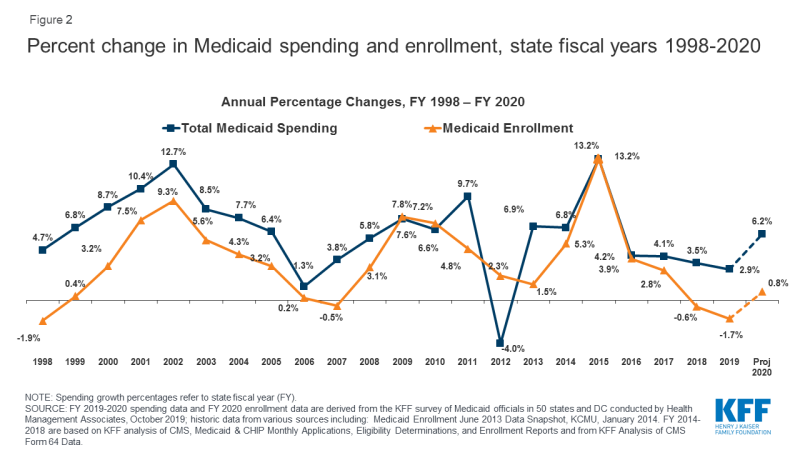

Enrollment: States largely attributed enrollment declines in FY 2019 (-1.7%) and relatively flat enrollment growth in FY 2020 (0.8%) to a stronger economy (Figure 1). A number of states, however, also pointed to changes in renewal processes, new functionality of upgraded eligibility systems, and enhanced verifications and data matching efforts as contributing to enrollment declines.

Figure 1: Medicaid enrollment and spending growth in state fiscal year 2019 and projected for FY 2020

Total Spending: Total spending growth slowed to 2.9% in FY 2019 primarily due to enrollment declines. For FY 2020, however, states adopted budgets with projected growth returning to more typical levels of 6.2% as higher costs for prescription drugs, provider rate increases, and costs for the elderly and people with disabilities (including increased utilization of long-term services and supports) are expected to put upward pressure on total Medicaid spending.

State Spending: Despite an increase in the state share of financing for the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) Medicaid expansion (from 6% in 2018 to 7% in 2019 and 10% in FY 2020 – midway through the state fiscal year), growth in the state share of Medicaid costs was lower than total spending growth in FY 2019 and budgeted to be similarly lower in FY 2020. Most expansion states reported relying on general fund support to finance the ACA Medicaid expansion, but a number of states also reported relying on provider taxes or other savings from the expansion.

Looking ahead: Looking ahead beyond FY 2020, economic conditions and the outcomes of federal and state elections in November 2020 are likely to have major implications for Medicaid, state budgets, and enrollees as debate about Medicaid expansion, demonstration waivers, the ACA, and broader health reform continue to be a major focus for candidates and voters.

Context

Medicaid (together with CHIP) provided coverage to about one in five Americans, or about 72 million people, as of July 2019.1 Total Medicaid spending was $593 billion in FY 2018 with 62.5% paid by the federal government and 37.5% financed by states.2 Medicaid accounts for one in six dollars spent in the health care system and more than half of spending on long-term services and supports.3 Since the end of the Great Recession, a steadily improving economy in most states has led to lower unemployment and improving state revenues. These trends can mitigate Medicaid enrollment growth while robust state revenue growth can support program expansions or enhancements such as benefit expansions or provider rate increases. According to the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), FY 2020 will likely mark the tenth straight year of state general fund spending increases following two years of decline in FY 2009 and FY 2010.4 Another key factor affecting Medicaid spending and enrollment is the implementation of the ACA’s coverage expansions beginning in 2014. As of October 2019, 37 states (including DC) have adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion with implementation expected in January 2020 in Idaho, in October 2020 in Nebraska (FY 2021) and in July 2020 in Utah if waiver options are not approved before then (also FY 2021).5

State revenue performance in FY 2019 was strong. NASBO reported that most states entered FY 2019 with budget surpluses from robust revenue growth in FY 2018. In its June report, NASBO estimated nominal general fund revenue growth of 7.0% in FY 2018 and 2.7% in FY 2019.6 Strong revenue growth allowed states to increase general fund spending by an average of 5.8% in FY 2019 and also bolster reserve funds.7

FY 2020 state budgets include increases for a variety of state priorities. By July 1, 2019, seven states (Massachusetts, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin) had not adopted a FY 2020 budget (compared to two states that had not adopted a FY 2019 budget at the same time last year). These budget impasses were primarily driven by policy disagreements rather than weak fiscal conditions.8,9 Across states, adopted budgets for FY 2020 increased spending for priority programs (early education, K-12 and higher education, and workforce development), provided one-time spending for infrastructure projects, and directed more dollars to build up state rainy day funds.10 Other areas for increased spending included Medicaid expansion (in a few states), child welfare services, behavioral health, affordable housing, corrections, expansion of broadband internet, water quality and clean energy initiatives, additional pension funding, and state employee pay raises and bonuses.11

Fiscal conditions vary across states but remain strong overall. Underneath national trends lies considerable state variation in fiscal conditions. For example, eight states reported flat or negative revenue growth in FY 2019 while 11 states experienced growth of 5% or more. Unemployment also varied across states with Alaska, Arizona, DC, Mississippi, and New Mexico reporting the highest state unemployment rates in August 2019, exceeding the national rate by one percentage point or more.12 Overall, the national unemployment rate remained steady at 3.7% in August 2019.13

Key Findings

Trends in Enrollment Growth FY 2019 and FY 2020

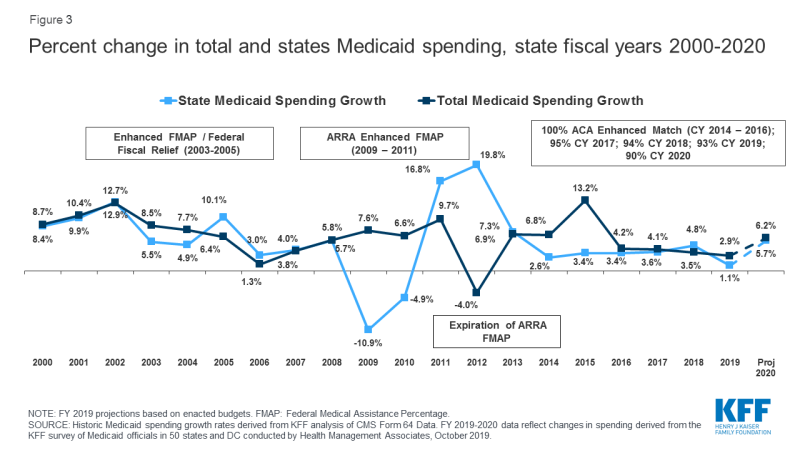

Medicaid enrollment declined in FY 2019 and is expected to be flat in FY 2020. Medicaid enrollment growth peaked in FY 2015 due to the implementation of the ACA and has tapered each year since, dropping to -0.6% in FY 2018 and -1.7% in FY 2019. For FY 2020, states project nearly flat enrollment growth of 0.8% overall (Figure 2) with fewer states (11 states) expecting enrollment declines compared to FY 2019 (35 states). States were more likely to report enrollment declines for children compared to other groups (expansion adults, seniors and people with disabilities, other adults) (data not shown).

States largely attribute Medicaid enrollment declines to improving economic conditions. Increased incomes generated by the strong economy may have resulted in Medicaid coverage losses for some low-income enrollees. However, recent Census Bureau data show an increase in the number of uninsured in the U.S., suggesting that some people losing Medicaid coverage may not gain access to employer-based health benefits and are not buying their own insurance.14 Some states also pointed to process and systems changes including changes to renewal processes, upgraded eligibility systems, and enhanced data matching efforts to verify eligibility as putting a downward pressure on enrollment.15 At least one state mentioned changes driven by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) guidance instructing states to tighten procedures related to verifying income changes as a cause of enrollment declines. In June 2019, CMS issued guidance to state Medicaid agencies outlining practices “to ensure that program resources are reserved for those who meet eligibility requirements.” The guidance spotlights use of periodic data matching between annual renewals to verify eligibility throughout the year.16 In line with other research,17 a few states also noted that the recently finalized public charge rule is expected to have a chilling effect on Medicaid enrollment of immigrant families, deterring eligible individuals from enrolling (or causing eligible individuals to disenroll).

Enrollment declines were mitigated by enrollment growth in some states. Eleven states reported enrollment growth in FY 2019 while 31 states are projecting enrollment growth in FY 2020, including a few states newly implementing or planning to implement the ACA Medicaid expansion in FY 2019 or FY 2020. Overall, states reported a higher median enrollment growth rate for the elderly and people with disabilities compared to other groups (expansion adults, other adults, and children) or as compared to the overall growth rate (data not shown). Higher enrollment growth for these high-cost enrollees contributes to a higher acuity case-mix, which will tend to increase spending per enrollee.

Trends in Spending Growth FY 2019 and FY 2020

Growth in total Medicaid spending slowed in FY 2019, but is expected to resume to more typical growth rates in budgets adopted for FY 2020. High rates of enrollment growth, tied first to the Great Recession and later to the implementation of the ACA, were the primary drivers of total Medicaid spending growth over the last decade. Similarly, declining enrollment driven by a strong economy was the primary driver identified by states for slow spending growth in FY 2019. While flat enrollment is projected to continue as a mitigating factor on spending in FY 2020, Medicaid officials identified increasing costs for prescription drugs (particularly for specialty drugs), rate increases (most often for managed care organizations, hospitals, and nursing facilities), as well as pressures from an aging population and a higher acuity case-mix as key upward pressures on total Medicaid spending. Some states noted that medical inflation, which trends higher than general inflation, results in higher Medicaid spending growth compared to other state programs. It is worth noting that actual spending growth for FY 2019 was lower than what was included in the FY 2019 budgets, so it is possible that actual spending for FY 2020 might be higher or lower than budgeted. During economic downturns, states may spend more than budgeted amounts and face shortfalls, requiring the need for supplemental funding.

Thirty states reported per enrollee growth was higher for certain groups, and about half of those pointed to higher growth for the elderly and people with disabilities (data not shown). A smaller number of states pointed to higher per enrollee growth for expansion adults. One of these states noted that broader enrollment declines in the expansion adult group resulted in a higher acuity level and higher per person cost for the remaining enrollees while another state commented that opioid treatment costs were especially high for expansion adults. The remaining states reporting higher growth in some groups were mixed with a few pointing to higher growth for children, pregnant women, or other more specific groups.

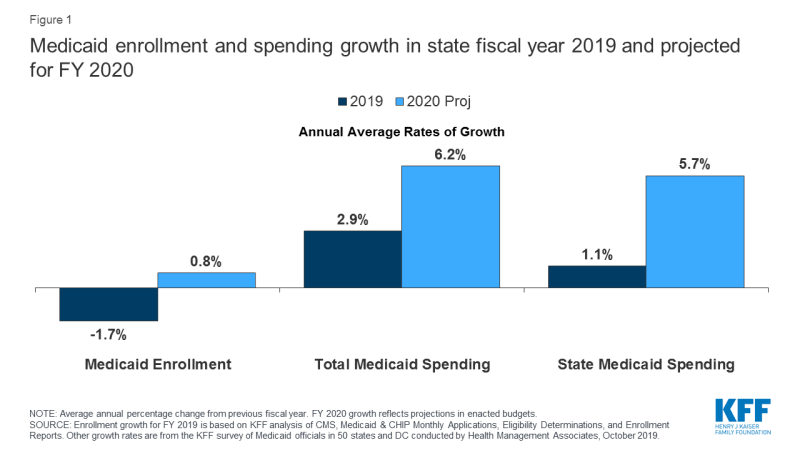

The state share of Medicaid spending typically grows at a similar rate to total Medicaid spending growth, unless there is a change in the federal matching rate. Following the implementation of the ACA, the enrollment of millions of expansion adults at a 100% federal match rate resulted in lower overall state spending growth compared to total spending growth. Mid-way through FY 2017, expansion states began paying 5% of the costs of the new group, and this amount increased to 6% in January 2018 and 7% in January 2019. In FY 2018, the first full state fiscal year states were responsible for paying for a share of the Medicaid expansion, state Medicaid spending growth slightly outpaced total Medicaid spending growth. This could be because the increase in 2017 was from 0% state share to 5% (comparatively larger than later, more incremental increases). In FY 2019, however, state spending growth was lower than total Medicaid spending growth (1.1% compared to 2.9%), despite the increase in the required state matching rate to 7%. In January 2020, the state share of costs for the expansion group will increase to 10% where it will stay in future years. Similar to FY 2019, states project that state spending growth will be slightly lower than total spending growth in FY 2020. Average state spending growth may be slower than total spending in FY 2019 and FY 2020 because of the marginally smaller increases in the state share of expansion costs (compared to the earlier jump from 0% to 5%); however, our survey data do not provide an explanation. In both FY 2019 and FY 2020, state Medicaid spending growth is moving in the same direction as total Medicaid spending growth (Figure 3).

In FY 2019, state spending growth for Medicaid was lower than overall general fund expenditure growth. State spending growth for Medicaid typically outpaces overall state general fund growth as medical costs have historically grown faster than inflation. During the first three years of ACA implementation (2014-2016), however, state spending for Medicaid grew at a slower pace compared to overall state general fund growth, likely due to the enhanced federal match rate for expansion adults that covered the full cost of the expansion in those years as well as slower growth in health costs generally, and the improving economy. While data in this report reflect state spending from general fund and other state sources, states reported estimated state Medicaid spending growth of only 1.1% in FY 2019 compared to 5.8% general fund expenditure growth (as reported by NASBO18). NASBO data also show state Medicaid general fund spending growing at a slower rate (3.6%) compared to total general fund spending (5.8%).

A number of states use provider taxes or savings from expansion to finance the state share of expansion costs. A large majority of states use general revenue to finance the state share of Medicaid expansion costs; however, 11 states use increases in existing or new provider taxes and seven states identified savings from expansion (e.g., in other state health programs) to finance these costs. Indiana and Louisiana reported using cigarette taxes or tobacco taxes to finance the expansion. Several expansion states reported multiple sources of financing.

Conclusion and Looking Ahead

A stronger economy as well as new enrollment systems and enhanced verifications contributed to declines in Medicaid enrollment in FY 2019 and flat growth projections for FY 2020. Enrollment declines accounted for low Medicaid spending growth in FY 2019, with state revenues increasing faster than state spending on Medicaid. Rising costs for prescription drugs, provider rate increases, and costs tied to the elderly and people with disabilities (including increased utilization of long-term services and supports) were cited as factors contributing to expected upward spending growth in FY 2020, even as enrollment growth is expected to remain flat. Looking ahead, the factors driving Medicaid spending growth are likely to continue and could be exacerbated in the event of a future economic downturn that would likely have significant effects on Medicaid enrollment and spending. As the debate heats up for the November 2020 elections, health care remains a key issue for candidates and voters at both the state and federal levels. At the state level, continued debates about Medicaid expansion, drug costs, and Section 1115 demonstration waivers will be important to watch. At the federal level, the health care debate is far-reaching. Democratic presidential candidates are proposing to further expand coverage while the Trump Administration continues to support policies that would eliminate the ACA and fundamentally restructure Medicaid with less federal funding. A strong economy and lower Medicaid enrollment growth relieve some fiscal pressure on states, but a future economic downturn as well as the outcomes of the elections could have significant implications for the Medicaid program, state budgets, and for Medicaid enrollees.