Key Themes in Capitated Medicaid Managed Long-Term Services and Supports Waivers

Key Themes

Covered Populations and Services

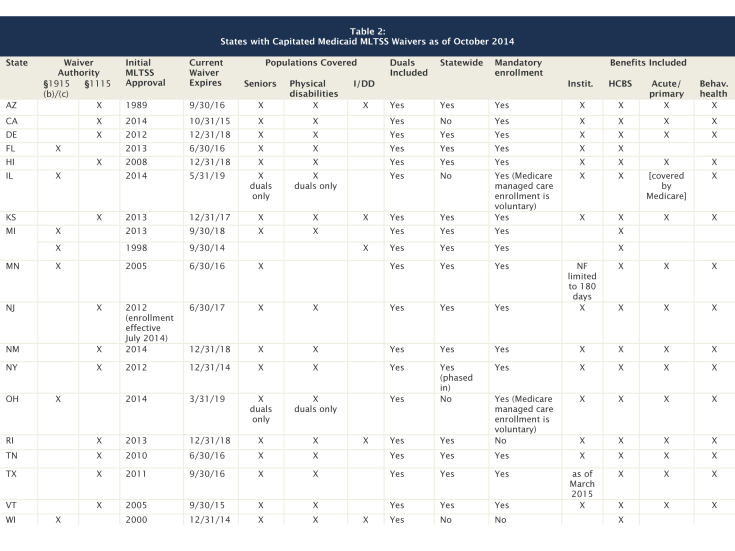

Given increased state interest and CMS’s 2013 guidance focused on § 1115 and § 1915(b) MLTSS waivers, this issue brief analyzes the special terms and conditions for 19 capitated MLTSS waivers approved to date. Basic features in these waivers are summarized in Table 2. Additional details about program features may be contained in the contracts between the state Medicaid agency and health plans or state regulations or policy guidance, which are not part of this analysis.

Key findings about the populations and services covered by current MLTSS waivers include the following:

- State interest in MLTSS is increasing, with over half (11 of 19) of these waivers approved in 2012, 2013, or 2014.1 By contrast, one state (AZ) has a long-standing MLTSS waiver, first approved in 1989.

- Twelve waivers use § 1115 demonstration authority for MLTSS, while seven waivers use combination § 1915(b)/(c) authority. (One state (KS) uses combination § 1115/1915(c) authority.) As noted above, while § 1915(b)/(c) waivers are focused on MLTSS, § 1115 MLTSS waivers often include additional features, such as other delivery system and financing reforms or eligibility or benefits provisions affecting other populations, as a result of the additional waiver and expenditure authorities available under § 1115.

- All 19 MLTSS waivers include seniors and non-elderly adults with physical disabilities, while five (AZ, KS, MI, RI, WI) include people with intellectual/developmental disabilities. All of the MLTSS waivers include dual eligible beneficiaries (for purposes of their Medicaid benefits), with two (IL and OH) limited exclusively to dual eligible beneficiaries. Six states (CA, IL, MI, NY, OH, TX) have concurrent § 1115A authority for financial alignment demonstrations that integrate Medicare and Medicaid benefits for dual eligible beneficiaries.

- Most (15 of 19) of the waivers are or will be providing MLTSS statewide. Four waivers (CA, IL, OH, WI) are limited to certain geographic areas in the state, and one state (NY) is in the process of phasing in statewide MLTSS.

- Most (17 of 19) of the MLTSS waivers (all except RI and WI) require beneficiaries to enroll in managed care to receive LTSS. This is accomplished primarily through passive enrollment in which beneficiaries are automatically assigned to a health plan if they do not affirmatively select one. For waivers that serve dual eligible beneficiaries and operate concurrently with § 1115A authority, enrollment in Medicare managed care (for primary care and other services for which Medicare is the primary payer) is voluntary.

- Most (14 of 19) of the waivers cover or will soon cover a comprehensive set of benefits, including nursing facility (NF) services, HCBS, acute and primary care, and behavioral health services. Minnesota’s waiver includes limited NF services, and Texas’ waiver will incorporate NF services as of March 2015. CMS’s 2013 guidance identifies a comprehensive integrated service package among MLTSS best practices and notes that including both institutional and HCBS in MCO capitation rates supports LTSS rebalancing.2 All of the comprehensive MLTSS waivers use private MCOs, with the exception of Vermont, in which the state operates as an MCO, and Illinois, which uses PIHPs. (IL’s waiver is limited to dual eligible beneficiaries, for whom Medicare is the primary payer for services such as acute and primary care.) One waiver (FL) uses PIHPs to cover only LTSS (NF and HCBS), with other services provided by other Medicaid managed care arrangements. Three waivers (2 in MI, WI) cover only HCBS through PIHPs or PAHPs.

Table 2 Notes and Sources

NOTES: Many of the § 1115 waivers include additional provisions not directly related to MLTSS.

California: MLTSS include in-home supportive services, community-based adult services, multipurpose senior services, and NF services but not other § 1915(c) waiver services.

Delaware: MLTSS also includes those with HIV/AIDS, TEFRA children, and working people with disabilities who buy-in to Medicaid; the managed care behavioral health benefit has a limited number of visits with the remainder covered FFS.

Kansas: § 1115 waiver operates concurrently with § 1915(c) waivers.

Hawaii: provides capitated acute and primary care services to people with I/DD, with ICF/IDD services and home and community-based waiver services provided FFS under separate § 1915(c) authority; MCOs provide standard behavioral health services, with specialized behavioral health services provided through a separate managed care carve out.

Illinois: § 1915(b)/(c) waiver does not include acute/primary care services but operates in conjunction with a § 1115A dual eligible financial alignment demonstration (in which Medicare managed care enrollment is voluntary). Also operates mandatory managed care for seniors and people with disabilities, including MLTSS, under § 1932 state plan authority.

Michigan: MLTSS waiver serving people with I/DD also includes people with serious mental illness.

New Jersey: also includes people with TBI and AIDS; LTSS for people with I/DD, those in the medication assisted treatment initiative, and children with SED at risk of institutionalization are FFS; beneficiaries in NFs as of July 1, 2014 will remain in FFS; anyone newly eligible for Medicaid and in a NF after July 1, 2014 will receive MLTSS.

New Mexico: transitioned its MLTSS program from a § 1915(b)/(c) waiver to a § 1115 waiver; also includes working people with disabilities eligible for buy-in, people with HIV/AIDS and those who are medically frail (initially for acute care only, with waiver services to be phased in from Jan. to July 2015); people receiving § 1915(c) I/DD waiver services are included in managed care for acute and behavioral health only.

New York: has a pending § 1115 waiver request seeking extension through December 2019; provides institutional and HCBS through mainstream Medicaid MCOs and MLTSS for beneficiaries who need more than 120 days of community-based LTSS (duals and NF eligible non-duals); pending waiver amendment to transition behavioral health state plan services to MCOs and include § 1915(i)-like services for people with significant behavioral health needs through specialized MCOs for those at risk of institutionalization.

Texas: transitioned its MLTSS program from a § 1915(b)/(c) waiver to a § 1115 waiver.

Vermont: pending waiver extension seeking to combine its MLTSS waiver with its §1115 managed care waiver in which the state serves as MCO and include all § 1915(c) waiver services, including I/DD. Under VT’s § 1115 waiver, which includes a global cap, the state’s primary care case management program operates as if it were a public sector risk-bearing MCO.

SOURCE: KCMU review of Section 1115 Demonstration Special Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/Waivers_faceted.html.

Provisions Aimed at Increasing Beneficiary Access to HCBS

As noted above, a number of states expect that incentives built into their MLTSS programs will increase beneficiary access to HCBS. Historically, the Medicaid program has had a structural bias toward institutional care because state Medicaid programs must cover NF services, while, as noted above, most HCBS are provided at state option. While states can choose to offer HCBS as Medicaid state plan benefits, the majority of HCBS are provided through waivers, which, unlike state plan benefits, can have enrollment caps, resulting in waiting lists when the number of people seeking services exceeds available funding.3 Over the last several decades, states have been working to rebalance their LTSS systems by devoting a greater proportion of spending to HCBS instead of institutional care, as a result of beneficiary preferences for HCBS, the fact that HCBS are typically less expensive than comparable institutional care, and states’ community integration obligations under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Olmstead decision. In addition, CMS’s 2013 guidance provides that MLTSS waivers should provide the “greatest opportunities for active community and workforce participation.”4

Table 3 summarizes MLTSS waiver provisions aimed at increasing beneficiary access to HCBS, including those that expand Medicaid financial eligibility criteria, provide HCBS to people at risk of institutional care, permit beneficiaries to include spouses as paid caregivers under the self-direction option, offer financial incentives for health plans to increase HCBS, and require health plans to implement certain features related to LTSS rebalancing.

Financial Eligibility Expansions

Four states use MLTSS waivers to increase access to HCBS by expanding Medicaid financial eligibility criteria:

- New Jersey streamlines financial eligibility for those who meet a NF level of care by using a projected spend-down that qualifies beneficiaries for Medicaid “home and community-based waiver-like services” if their monthly income exceeds annual average nursing facility costs.5 New Jersey’s waiver also eliminates the five year asset transfer look-back period for applicants seeking LTSS with income at or below 100% FPL ($11,670 per year for an individual in 2014).

- New York applies a special income standard when determining financial eligibility for people who are discharged from a nursing facility and would be eligible for HCBS via a spend down but for the spousal impoverishment rules. Specifically, New York determines financial eligibility for this population by subtracting 30% of the Medicaid income limit for an individual (considered to be available for housing costs) from the HUD average fair market rent for the geographic region.

- Rhode Island allows applicants who meet functional eligibility criteria and self-attest to financial eligibility criteria to receive a limited package of LTSS up to 90 days while a final financial eligibility determination is pending. The limited benefit package includes personal care/homemaker services up to 20 hours per week and/or adult day services up to 3 days per week and/or limited skilled NF services. Rhode Island’s waiver also increases the personal needs allowance by $400 for those in NFs for 90 days who are transitioning to the community and who would be unable to afford a community placement without the increased funds.

- Vermont increases the asset limit to $10,000 for single beneficiaries in the “highest” and “high” need groups who own and reside in their own homes and receive HCBS but are at risk of institutionalization. Vermont’s waiver also provides an entitlement to both nursing facility and HCBS to beneficiaries in the “highest” need group, with services available to all who meet the eligibility criteria, without a waiting list.

HCBS for People at Risk of Institutionalization

Seven states use or are seeking MLTSS waiver authority to provide HCBS to people at risk of institutionalization. (States also can provide HCBS to beneficiaries who meet functional criteria that are less strict than those required to meet an institutional level of care under § 1915(i) state plan authority.) NJ’s waiver also provides HCBS to at risk groups, although those beneficiaries are exempt from MLTSS enrollment.

- Arizona includes a “transitional program” that provides institutional services limited to 90 days per admission plus acute, behavioral health, HCBS, and case management services to beneficiaries who are not at “immediate risk” of institutionalization when eligibility is redetermined.

- Delaware provides HCBS to beneficiaries at risk of institutionalization for those with incomes below 250% of the Supplemental Security Income federal benefit rate (SSI FBR, $21,630 per year for an individual in 2014).

- New York is seeking a waiver amendment that would allow it to offer Medicaid state plan, health home, and § 1915(i)-like HCBS (such as behavioral supports in residential, day, and home settings) to adults with behavioral health diagnoses who meet certain risk factors and targeting and functional criteria.

- Rhode Island provides HCBS to beneficiaries at risk of institutionalization, including seniors and adults with dementia with income at or below 250% FPL ($29,175 per year for an individual in 2014) and adults with disabilities with income at or below 300% SSI FBR ($25,956 per year for an individual in 2014) who have income and/or assets otherwise above Medicaid eligibility limits.

- Hawaii, Tennessee, and Vermont also provide HCBS to beneficiaries at risk of institutionalization. Vermont offers a limited benefit package (including adult day, case management, and homemaker services) to beneficiaries in the “moderate need” group who do not yet meet a NF level of care; a pending waiver amendment would expand the “moderate need” benefit package.

Self-Direction Includes Spouses as Paid Caregivers

Two states (AZ and VT) use MLTSS waiver authority to allow beneficiaries to employ spouses as paid caregivers as part of their option to self-direct HCBS.

Financial Incentives for increased HCBS

Three states’ MLTSS waivers include financial incentives for health plans that provide increased HCBS. This is consistent with CMS’s guidance, which requires states to “employ financial incentives that achieve desired outcomes [according to the state’s MLTSS program goals] and/or impose penalties for non-compliance or poor performance.”6

- Hawaii and Ohio’s waivers authorize financial incentives and penalties related to HCBS capacity in MCO contracts. Specifically, Hawaii’s MCO contracts may contain financial incentives for expanded HCBS capacity, beyond annual thresholds established by the state, as well as sanctions penalizing MCOs that fail to expand community capacity at an appropriate pace. Hawaii MCOs that receive financial incentives for expanding HCBS capacity must share a portion with providers but may not pass along sanctions to providers. Ohio provides three months of incentive payments to MCOs equal to the difference between the “community well” and NF capitated rates for beneficiaries who transition from a NF or HCBS waiver that requires a NF level of care to a community placement with overall improved health outcomes such that the beneficiary no longer requires a NF level of care. Ohio MCO payments also are reduced, by the difference between the community well and NF capitated rates, for three months for each beneficiary entering a NF.

- Tennessee’s waiver allows MCOs to offer HCBS as a cost-effective alternative even if the enrollment target for HCBS has been met.7

Illinois’ concurrent § 1115A waiver provides similar financial incentives. Specifically, Illinois health plans receive an enhanced rate for three months after a beneficiary transitions from a NF to the community and a reduced rate for three months after a beneficiary transitions from the community to a NF.8

In addition, two states’ MLTSS waivers include provisions for increased HCBS funding.

- Kansas’ waiver provides that the state will designate a portion of the savings realized through managed care to increase the number of § 1915(c) HCBS waiver slots to serve beneficiaries on the waiting list, subject to state legislative appropriations.

- Vermont’s waiver provides that the state will add resources equivalent to at least 100 additional HCBS waiver slots per year over 10 years to further the demonstration’s goal of serving more beneficiaries by increasing HCBS relative to institutional services.

MCO Requirements for NF Transitions or Diversion

Three states’ waivers include requirements for MCOs regarding NF to community transitions or NF diversion. CMS’s MLTSS guidance provides that states “should ensure that their service packages include services to support participants as they transition between settings.”9

- Kansas MCOs must meet and report on annual Money Follows the Person (MFP) NF transition benchmarks.10 In the waiver terms and conditions, CMS encourages Kansas to consider policies to incentivize MCOs to help the state meet or exceed its MFP benchmarks or self-direction goals.

- New Jersey MCOs must have a NF diversion plan, approved by the state and CMS, for beneficiaries receiving HCBS and those at risk of NF placement, including short-term stays, and must monitor hospitalizations and short stay NF services for at risk beneficiaries. MCOs also are responsible for identifying beneficiaries in institutions who are appropriate for community transitions and developing, with state assistance, a NF transition plan for each beneficiary who has requested and can safely transition. New Jersey’s waiver also requires MCOs to emphasize services in home and community-based settings whenever possible. MCOs may refuse to offer HCBS if the cost exceeds institutional care, but the state can make individual exceptions, such as cases in which a beneficiary transitions from an institution to the community, when a beneficiary experiences a change in health condition expected to last no more than six months that involves additional significant cost, or special circumstances to accommodate unique beneficiary needs.

- New Mexico MCOs must develop and facilitate transition plans for beneficiaries who are candidates for NF to community moves.

Person-Centered Planning and Home and Community-Based Setting Requirements

A number of the MLTSS waivers require person-centered planning11 and/or the provision of services in home and community-based settings. These elements are now required across Medicaid HCBS authorities pursuant to CMS’s January 2014 regulations and apply to MLTSS waivers pursuant to CMS’s 2013 guidance.12 CMS’ guidance directs states to “require MCOs to offer services in the most integrated setting possible.”13 Some examples of MLTSS waiver terms and conditions regarding home and community-based settings that pre-date the 2014 regulations include:

- Florida requires health plan contracts to include residential providers’ responsibility to meet “home-like environment” and community inclusion goals.

- Hawaii and Kansas’ waivers require that the state either directly or through its MCO contracts ensure that beneficiaries’ engagement and community participation is supported and facilitated to the fullest extent. Hawaii also requires its MCOs to provide options counseling about institutional vs. home and community-based settings and to emphasize HCBS to prevent or delay institutionalization whenever possible when developing care plans. Kansas requires that beneficiaries receive appropriate services in the least restrictive environment and most integrated home and community-based setting and that MCOs record the alternative HCBS and settings considered by the beneficiary as part of the person-centered planning process.

- New Jersey and New Mexico require that beneficiaries have the option to receive HCBS in more than one residential setting appropriate to their needs.

| Table 3: Provisions Affecting HCBS Access in Capitated Medicaid MLTSS Waivers as of October 2014 |

|||||

| State | Financial Eligibility Expansions | Includes HCBS for Those at Risk of Institutional Care |

Self-Direction Includes Spouses as Paid Caregivers | Financial Incentives for MCOs to Increase HCBS |

MCO Requirements for NF Transition/ Diversion |

| AZ | X | X | |||

| DE | X | ||||

| HI | X | X | |||

| IL | (included in concurrent § 1115A demonstration) |

||||

| KS | (state to use portion of managed care savings to increase § 1915(c) HCBS waiver slots) |

X | |||

| NJ | X | (MLTSS exempt) | X | ||

| NM | X | ||||

| NY | X | amendment pending | |||

| OH | X | ||||

| RI | X | X | |||

| TN | X | X | |||

| VT | X | X | X |

(state to add equivalent of

at least 100 HCBS

waiver slots per

year over 10 years)

|

|

| SOURCE: KCMU review of Section 1115 Demonstration Special Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/Waivers_faceted.html. | |||||

Beneficiary protections

Beneficiaries who need HCBS often rely on those services to meet basic daily needs and support independent living in the community. They also may need a higher intensity of services than other Medicaid beneficiaries. These factors make them particularly vulnerable to potential service disruptions. The Medicaid program includes a basic set of beneficiary protections, such as the right to adequate notice and a fair hearing, grounded in the Due Process Clause of the U.S. Constitution.14 As noted above, the Medicaid managed care state plan authority at § 1932 and 42 C.F.R. Part 438 contain additional safeguards specific to managed care arrangements. In addition, CMS’s 2013 guidance provides that MLTSS waivers should include stakeholder engagement in MLTSS implementation and oversight and offer support for beneficiaries, including conflict-free choice counseling, independent advocacy or ombudsman services, and enhanced opportunities for disenrollment.

Table 4 summarizes MLTSS waiver provisions that provide beneficiary protections in the areas of independent enrollment counseling, ombudsman programs, health plan disenrollment, and managed care advisory groups.

Independent Enrollment Counseling

Eight states’ waivers include provisions for independent enrollment options counseling to assist beneficiaries with choosing a health plan. CMS’s MLTSS guidance requires states to provide beneficiaries with enrollment choice counseling that is independent of health plans, service providers, and entities making eligibility determinations.15

- Four states (CA, HI, NY, TX) use their ombudsman program to provide beneficiaries with independent health plan options counseling.

- Four states (FL, IL, KS, OH) use an enrollment broker to provide independent options counseling. Florida’s MLTSS waiver provides that enrollees will receive choice counseling either by phone or in-person. Kansas’ waiver requires independent options counseling for beneficiaries transitioning to MLTSS from § 1915(c) waivers. In addition, Illinois received funding available through its dual eligible financial alignment demonstration for SHIPs and/or ADRCs to provide options counseling.16

Ombudsman Programs

Eleven states’ waivers provide for an ombudsman program as part of their demonstrations. In general, these programs must function independently of health plans and the state Medicaid agency, be available to all beneficiaries or all those receiving MLTSS, be accessible by a variety of means (such as phone, email, in-person) and conduct outreach through a variety of methods (such as mail, phone, in-person). Ombudsman programs typically are charged with helping beneficiaries access covered services and tracking and assisting beneficiaries with complaints. CMS’s guidance requires states to “ensure an independent advocate or ombudsman program is available to assist participants in navigating the MLTSS landscape; understanding their rights, responsibilities, choices, and opportunities; and helping to resolve any problems that arise between the participant and their MCO.”17

- In nine states, the ombudsman program is specifically authorized to assist beneficiaries with the appeals process (CA, HI, IL, KS, MN, NM, NY, OH, TX). Hawaii’s waiver provides that the ombudsman can represent beneficiaries in appeals up to the administrative fair hearing level and assist, but not represent, beneficiaries at fair hearings. Kansas’s waiver provides that the ombudsman can assist beneficiaries with filing appeals and can mediate appeals but cannot represent beneficiaries. Minnesota’s waiver also provides that the ombudsman can resolve appeals through negotiation or mediation.

- Five states’ waivers (IL, KS, NM, NY, TX) contain additional detail about ombudsman functions and responsibilities, including that the ombudsman train health plans and providers; employ staff knowledgeable about Medicaid managed care and people with disabilities; provide services in a culturally competent manner and in a way that is accessible to people with disabilities and those with limited English proficiency; and regularly and publicly report on beneficiary complaints and appeals.

- Three states’ waivers (FL, IL, OH) identify the state long-term care ombudsman as the entity that will provide ombudsman services for beneficiaries receiving MLTSS.

- In Hawaii, the ombudsman may be a member of the care team at a beneficiary’s request.

Three states’ waivers (NJ, RI, VT) do not provide for an ombudsman program but instead require that beneficiaries have access to an independent advocate within the state, such as the state protection and advocacy agency for people with disabilities, a legal services agency, or the Area Agency on Aging.

Beneficiary Ability to Change MCOs if Provider Leaves Network

Six states’ MLTSS waivers include provisions that expand beneficiaries’ right to change MCOs for cause outside of open enrollment. CMS’s guidance requires states to allow beneficiaries to disenroll from their MCO “when the termination of a provider from their MLTSS network would result in a disruption in their residence or employment.”18

- Florida allows beneficiaries to request to change health plans if their provider leaves the network. The waiver specifies that such requests “would be considered for good cause.”

- Illinois allows beneficiaries to change health plans for cause if their LTSS provider leaves the network.

- Hawaii, Kansas, and New Mexico allow beneficiaries to change MCOs if their residential or employment supports provider leaves the network (limited to residential providers in Kansas).

- Kansas also permits enrollees with an existing LTSS service plan who are transitioning from FFS or another MCO to change MCOs within 30 days of the initial service assessment due to the beneficiary’s experience with the MCO’s service planning process. This option is limited to one change annually.

- Hawaii also allows beneficiaries on an HCBS waiting list to change MCOs if HCBS appear to be available through another MCO. Similarly, Tennessee allows beneficiaries to disenroll from their MCO if LTSS are needed and available through another MCO, and the current MCO cannot provide the services even on an out-of-network basis.

Managed Care Advisory Groups

Seven waivers (CA, IL, KS, NJ, NM, NY, TX) require the state to maintain a managed care advisory group, including beneficiaries and other stakeholders, to provide input on the MLTSS program, and six (KS, NJ, NM, OH, TX, WI) require MCOs to establish beneficiary advisory groups. CMS’s guidance requires that a state MLTSS advisory group must include “cross-disability representatives” and that beneficiaries “be offered supports to facilitate their participation, such as transportation assistance, interpreters, personal care assistants and other reasonable accommodations, including compensation, as appropriate.”19 CMS also “expects states to require MCOs to convene accessible local and regional member advisory committees to provide feedback on MLTSS operations, and to encourage participation, MCOs also must provide beneficiary supports and compensation as appropriate.20

Three waivers (KS, NM, TX) require MCOs to facilitate and support beneficiary involvement in the advisory group. Ohio’s waiver specifies that MCOs must have a process for the beneficiary advisory committee to provide input to the MCO’s governing board and that people with disabilities, including plan enrollees, must be included within the plan’s governance structure.

Continuity of Care During Delivery System Transition

Waivers that are implementing new MLTSS programs often include provisions designed to promote continuity of care during beneficiary transitions from FFS to managed care. These provisions ensure beneficiary access to previously authorized services and/or providers for a certain period of time after transition, often until the new health plan completes an assessment and either the beneficiary agrees to a new care plan or the care plan is resolved through the appeals process. CMS’s guidance “expects states to include contract language around continuity and coordination of care for the transition. . . [which] may include. . . maintaining existing provider-recipient relationships as well as honoring the amount and duration of an individual’s authorized services under an existing service plan.”21

Continuation of LTSS While Appeals Are Pending

“Because of the significant reliance participants have on receipt of LTSS and the potential harm resulting from abrupt termination of LTSS, CMS expects states to adopt policies that ensure authorized LTSS continue to be provided in the same amount, duration, and scope while a modification, reduction, or termination is on appeal.”22 Hawaii and Kansas’ waivers specifically require the state to ensure that LTSS continue while appeals are pending.

Disability Accessibility

California’s waiver is the only state to mention physical accessibility for people with disabilities. The waiver provides that the state will use a facility site review tool to ensure health plan accessibility or contingency plans.

| Table 4: Beneficiary Protections in Capitated Medicaid MLTSS Waivers as of October 2014 |

|||||||

| State | Independent Enrollment Choice Counseling Provided |

Ombudsman

Program

|

Beneficiary Able to Change MCOs if Certain HCBS Providers Leave Network | State Managed Care Advisory Group | MCO Beneficiary Advisory Group | ||

| By Ombudsman | By Enrollment Broker | ||||||

| CA | X | X | X | ||||

| FL | X | X | X | ||||

| HI | X | X | X (also can disenroll if on HCBS waiting list and services available in another MCO) | ||||

| IL | X | X | X | X | |||

| KS | X | X | X (also can disenroll due to dissatisfaction with MCO service planning experience) | X | X | ||

| MN | X | ||||||

| NJ | (beneficiaries must have access to independent advocate) | X | X | ||||

| NM | X | X | X | X | |||

| NY | X | X | X | ||||

| OH | X | X | X | ||||

| RI | (beneficiaries must have access to independent advocate) | ||||||

| TN | (can disenroll if needed LTSS available through another MCO) | ||||||

| TX | X | X | X | X | |||

| VT | (beneficiaries must have access to independent advocate) | ||||||

| WI | X | X | |||||

| SOURCE: KCMU review of Section 1115 Demonstration Special Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/Waivers_faceted.html. | |||||||

Quality Measures and Oversight

LTSS performance measures are not as well developed as those for care provided in clinical settings, and work is continuing in this area. CMS’s MLTSS guidance requires states to “have a quality strategy in place at the time of implementation of their new, expanded, or modified MLTSS program.”23 States must have a “comprehensive quality strategy. . . [that is] transparent and appropriately tailored to address the needs of the MLTSS population.”24 In 2014, CMS modified its § 1915(c) HCBS waiver quality measures, which include level of care determinations; service plan adequacy; provider qualifications; abuse, neglect and exploitation; financial accountability; and state oversight.25 CMS also has awarded Testing Experience and Functional Assessment Tools planning grants to states to use health information technology to develop HCBS quality measures.26

In addition, some state-specific LTSS quality measures are being used in the financial alignment demonstrations for dual eligible beneficiaries. For example, Massachusetts includes a measure of the percent of beneficiaries with LTSS needs who have an LTSS coordinator, and Virginia and South Carolina include multiple LTSS measures, such as those related to beneficiary use of self-direction, increases and decreases in authorizations of specific HCBS to movement between institutional and community-based care settings, and level of care assessments. Other financial alignment demonstration states indicate that they will monitor (unspecified) measures of community integration and beneficiary quality of life.27

Other recent initiatives focused on the development of measures such as quality of life and community integration include:

- The National Quality Forum (NQF) is undertaking a two year project to identify gaps and recommend priorities for HCBS measure development and use.28

- In 2014, the NQF’s Measure Application Partnership issued stakeholder recommendations for quality measures related to dual eligible beneficiaries, including strategies to measure quality of life.29

- The National Council on Disability’s 2013 report on Medicaid managed care for people disabilities includes recommendations to state and federal policymakers on quality measures.30

- The National Association of States United for Aging and Disabilities’ National Core Indicators initiative is piloting an annual in-person survey in Georgia, Minnesota, and Oregon to assess quality of life and outcomes for seniors and adults with physical disabilities.31

- A group of beneficiary advocacy organizations issued recommendations for measuring LTSS rebalancing in the dual eligible financial alignment demonstrations and MLTSS waivers.32

- In 2012, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality issued its Medicaid HCBS Measure Scan, which identifies existing measures related to HCBS program performance, client functioning and client satisfaction.33

- The President’s Committee for People with Intellectual Disabilities’ 2012 report to the President on MLTSS includes recommendations on the development of quality measures.34

- The National Core Indicators project, a collaboration between the National Association of State Directors of Developmental Disabilities Services and the Human Services Research Institute, gathers performance and outcome measures for the I/DD population, with a focus on employment, rights, service planning, community inclusion, choice, and health and safety.35

Quality of Life Measures

Eight MLTSS waivers mention quality of life measures, although generally little detail is provided in the waiver terms and conditions. CMS requires states and/or MCOs to “measure key experience and quality of life indicators for MLTSS participants” with survey results publicly available.36

- Wisconsin’s care managers and quality assessors use a validated interview tool to assess beneficiary and care team perceptions of quality of life and whether outcomes are being achieved in the areas of self-determination and choice, community integration, and health and safety. Wisconsin’s quality strategy also includes population-based health indicators, such as changes in functional status over time.

- Six other MLTSS waivers mention quality of life measures with no further detail provided or with specific measures still to be identified. These include:

- California, which must develop mandatory MCO reports (with specifics included in MCO contracts) and “measure key experience and quality of life indicators.”

- Kansas, which must submit performance measures to CMS within one year of MLTSS implementation, which should focus on the outcomes of person-centered goals, quality of life, effective processes (such as level of care determinations and person-centered planning), and community integration, and show consistency in reporting across HCBS waivers.

- New Jersey, whose HCBS quality strategy must include outcomes related to quality of life.

- New Mexico, which must submit its quality strategy to CMS within 90 days of demonstration approval; any revised performance measures should reflect stakeholder input and focus on outcomes, quality of life, effective processes and community integration for those receiving HCBS.

- New York, which should incorporate performance measures for outcomes related to quality of life and community integration.

- Tennessee, which must submit its quality improvement strategy to CMS and identify measures of process, health outcomes, functional status, quality of life, member choice, autonomy, satisfaction and system performance.

In addition, Illinois’ concurrent § 1115A waiver requires measurement of beneficiaries’ perception of quality of life.

Rebalancing and Community Integration Measures

Five MLTSS waivers require reporting on LTSS rebalancing and community integration measures.

- California MCOs must track the number of referrals to HCBS waivers and assessments completed by HCBS providers; the number of referrals and completed assessments for in-home services and supports; the number of referrals to HCBS programs for newly admitted NF residents without a discharge plan in place; the number and proportion of beneficiaries who transition from institutional to community settings who are not re-institutionalized within one year; the number and proportion of beneficiaries receiving HCBS; and the number and proportion of beneficiaries receiving institutional services.

- Kansas must report to CMS on the number of people in NF and ICF/DDs and on waiver waiting lists; the number of people who move off waiting lists and the reason; the number of people new to the waiting lists; and the number of people on a waiting list but receiving HCBS through managed care. Kansas’s demonstration evaluation must assess whether the demonstration reduces the percentage of beneficiaries in institutions by providing additional HCBS and improves service quality by integrating and coordinating physical, behavioral health, and LTSS, the impact of including LTSS in the capitated benefit with a subfocus on HCBS; and ombudsman’s assistance to beneficiaries.

- New York must report on MCO rebalancing efforts, including the total number of transitions in and out of NFs each quarter.

- Ohio MCOs must report on LTSS measures, with a subset used to determine the quality withhold. Further details about these measures are contained in Ohio’s concurrent § 1115A waiver. The measures include:

- Quality withhold measures related to LTSS:

- Number of beneficiaries who did not reside in a NF (>100 continuous days) as a proportion of the total number of beneficiaries in the MCO

- Number of beneficiaries who lived outside a NF during the current year as a proportion of the number of beneficiaries who lived outside a NF during the previous year (>100 continuous days)

- Quality measures related to LTSS:

- Percent of all long-stay NF residents whose need for help with late-loss ADLs increased when compared with previous assessment (bed mobility, transferring, eating, toileting)

- Number of beneficiaries who were discharged from NF to community setting and did not return to NF during the current year as a proportion of the number of beneficiaries who resided in a NF during the previous year

- Number of beneficiaries who were in a NF during the current year, previous year, or combination of both years who were discharged to a community setting for at least 9 months during the current year as a proportion of the number of enrollees who resided in a NF during the current year, previous year or combination of both years (>100 days)

- Quality withhold measures related to LTSS:

- Tennessee must report to CMS on the number of people receiving NF or HCBS at a point in time and over 12 months; HCBS and NF expenditures for 12 months, the average during 12 months and as a percent of total LTSS spending; the average length of stay in NF and HCBS in a 12 month period; the percent of new LTSS beneficiaries admitted to a NF in a 12 month period; and the number of transitions from NF to HCBS in a 12 month period.

In addition, Illinois’ concurrent § 1115A waiver includes the following LTSS performance measures:

- Quality withhold measure in demonstration years 2 and 3: number of beneficiaries moving from institutional to waiver services (excluding institutional stays of 90 days or less)

- Quality measure: number of beneficiaries moving from institutional to waiver services, community to waiver services, community to institutional care, and waiver to institutional care (excluding institutional stays of less than 90 days)

Beneficiary Satisfaction Surveys

Five MLTSS waivers provide for beneficiary satisfaction surveys. Four states (FL, IL, MN, OH) use the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey. In addition, Wisconsin health plans must participate in a program-wide beneficiary satisfaction survey. Vermont’s waiver provides that beneficiaries on a waiting list will be included in any surveys or evaluations.

Encounter Data

Four MLTSS waivers (CA, DE, HI, NY) require reporting of health plan encounter data. CMS’s MLTSS guidance requires states to collect and report person-level encounter data as part of quality oversight and monitoring.37

State Monitoring of Service Plan Decreases By MCOs

Three MLTSS waivers require state monitoring of service decreases proposed by health plans. CMS’s guidance requires states to provide “enhanced monitoring of any service reductions. . . during the transition to managed care.”38

- The Kansas state department of aging and disability services must review and approve all care plans for beneficiaries with I/DD in FY 2014 and 2015, in which a reduction, suspension, or termination of services is proposed. The process and criteria for these reviews and approvals or denials must be publicly available. In addition, in 2014, Kansas must ensure that beneficiaries who are receiving some but not all requested I/DD waiver services will have all of their assessed service needs met within six months of MLTSS implementation and will review capitation rates with MCOs once all I/DD service needs are identified. Kansas also must observe and assist in needs assessments and service planning by participating in ride-alongs with each MCO during the first six months of MLTSS for beneficiaries with I/DD.

- New Mexico must review and approve a sample of all proposed service plan reductions, prior to implementation, in the first six months of MLTSS. Thereafter, the state or managed care external quality review organization must review a sample of service plan reductions at least annually.

- New York MCOs must report monthly on notices issued and appeals received regarding reductions in split shift or live-in services or reductions of hours by 25% or more.

State Monitoring of Grievances and Appeals

Three waivers include provisions regarding state monitoring and reporting on grievances and appeals, in addition to ombudsman program reporting on grievances and appeals (discussed above). CMS’s guidance expects states to “intervene if [MCO] service authorization processes regularly result in participant appeals of service authorization reductions or expirations.”39

- New Mexico must review each MCO’s appeal logs monthly during the first six months of MLTSS implementation.

- Texas also must monitor grievances and appeals. Both New Mexico and Texas’ reviews are to focus on beneficiaries transitioning to MLTSS from a § 1915(c) HCBS waiver.

- New York must report to CMS on the total number of complaints, grievances, and appeals by type of issue.

Performance Improvement Projects and Care Quality Studies

CMS’s guidance provides that states “should establish systemic performance improvement projects specific to the common elements of MLTSS for all MCOs providing MLTSS (i.e. related to deinstitutionalization).”40

- Ohio MCOs must complete one clinical and one non-clinical performance improvement project, with potential topics to include LTSS, NF care and/or rebalancing, and NF diversion.

- Florida plans must perform at least two quality of care studies.

- Illinois will hire an independent evaluation for its MLTSS waiver and other care coordination initiatives.