It Pays to Shop: Variation in Out-of-Pocket Costs for Medicare Part D Enrollees in 2016

Part D enrollees can expect to pay thousands of dollars out of pocket for a single specialty drug in 2016, even after their drug costs exceed the catastrophic coverage threshold

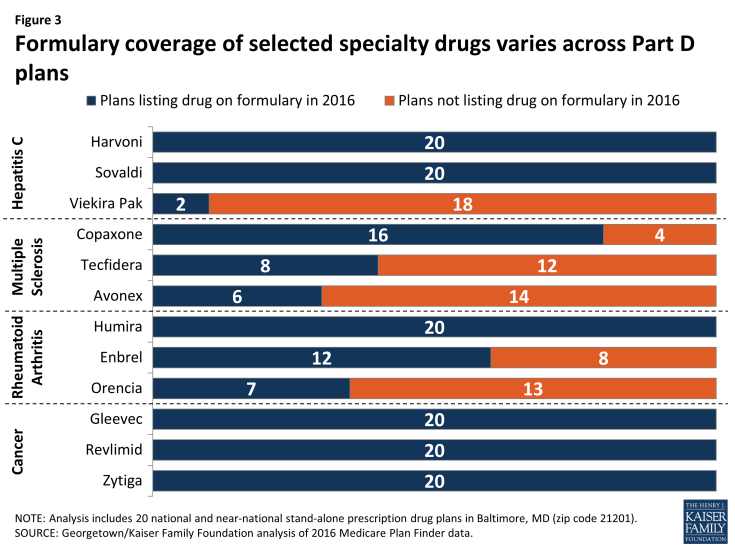

Specialty drugs, defined by Medicare as those that cost more than $600 per month, can contribute to high out-of-pocket costs for Part D enrollees. For 12 specialty drugs used to treat four health conditions —hepatitis C, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and cancer—Part D enrollees face at least $4,000 and as much as nearly $12,000 in annual out-of-pocket costs in 2016 for one drug alone (Figure 1). (See Appendix Table 1 for drug-specific cost information.)

Figure 1: Even with catastrophic coverage, Medicare Part D enrollees can pay thousands of dollars annually for specialty drugs

Among the studied 12 specialty drugs median out-of-pocket costs are lowest for the three drugs used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. But these costs still range from $4,413 to $4,872 for a year’s treatment. Median out-of-pocket costs for Medicare beneficiaries taking any one of three hepatitis C specialty drugs range from $6,516 to $7,153 in 2016. Some cancer drugs cost Part D enrollees even more. Revlimid, used to treat cancer of the blood, including multiple myeloma and a form of lymphoma, has a median out-of-pocket cost of $11,538, while Gleevec (for certain types of leukemia) has a median out-of-pocket cost of $8,503.

At least one-third of total out-of-pocket costs for each of these 12 specialty tier drugs are incurred by Part D enrollees after their spending reaches the catastrophic coverage phase of the Part D benefit. For seven of these drugs, enrollees pay more than half of their total out-of-pocket costs above the catastrophic threshold. For example, 58 percent of an enrollee’s out-of-pocket costs for Sovaldi (a treatment for hepatitis C) occur in the catastrophic coverage phase, which translates to $3,828 in costs in the catastrophic phase in 2016. For Revlimid, this share rises to 76 percent, or $8,758 in out-of-pocket costs in the catastrophic coverage phase. These examples assume that the particular specialty drug in question is the only drug taken by a Part D enrollee. In the likely event that they take other drugs, the share of costs in the catastrophic phase will be even greater.

Part D enrollees taking high-cost specialty tier drugs often incur significant costs beyond the catastrophic threshold because the threshold is not an absolute limit on out-of-pocket spending. By law, Part D enrollees pay 5 percent of drug costs after exceeding the catastrophic threshold (equivalent to $7,515 in total drug costs in 2016 under the standard benefit).1 Therefore, despite having catastrophic coverage, Part D enrollees can face thousands of dollars in annual out-of-pocket costs if they take expensive drugs (or, as described later, if they take multiple high-cost brand-name drugs).

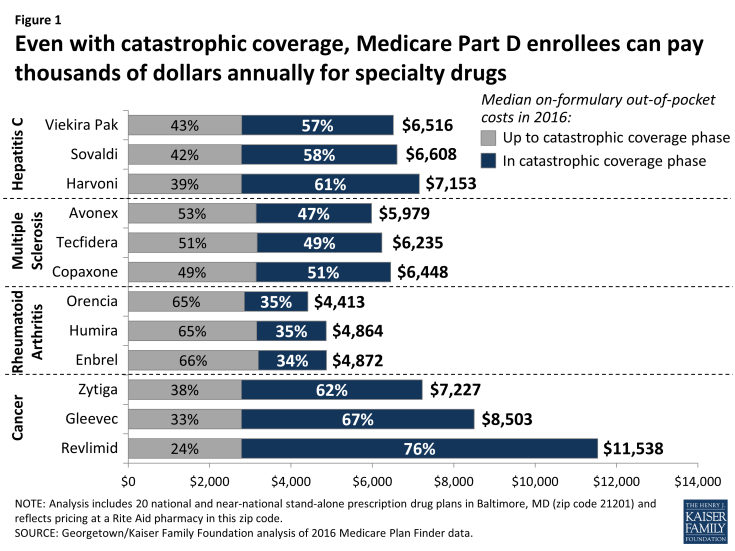

Part D enrollees who take specialty drugs face especially high costs at the start of the year (Figure 2). To illustrate, beneficiaries enrolled in the SilverScript Choice PDP face out-of-pocket costs of $6,221 in 2016 for Copaxone, a drug used to treat multiple sclerosis with a full cost of about $74,000. But they are liable for $2,404—over a third of the full year’s cost—in January. In this example, costs drop to $704 in February and then to $311 per month for the rest of the year. Similar patterns of front-loaded spending occur in other PDPs and for other high-cost specialty drugs. For enrollees who take specialty drugs over multiple years, the pattern repeats.

Figure 2: Part D enrollees’ out-of-pocket costs for many specialty drugs are substantial at the start of the year, and continue even after spending exceeds the catastrophic coverage threshold

This pattern occurs because the Part D benefit includes an initial coverage period during which enrollees pay from 25 percent to 33 percent (and, for two-thirds of plans, a deductible). The monthly cost of many specialty drugs is greater than the initial coverage limit ($3,310 in 2016), so enrollees shift quickly into the gap phase, during which enrollees pay 45 percent of the drug’s cost by statute (in 2016). Once the catastrophic threshold ($7,515 in total drug costs in 2016) is passed, enrollees pay 5 percent of the drug’s cost for the rest of the year.

Out-of-pocket costs are substantially higher—often ten times higher or more—for specialty drugs when they are not listed on formulary by a Part D plan

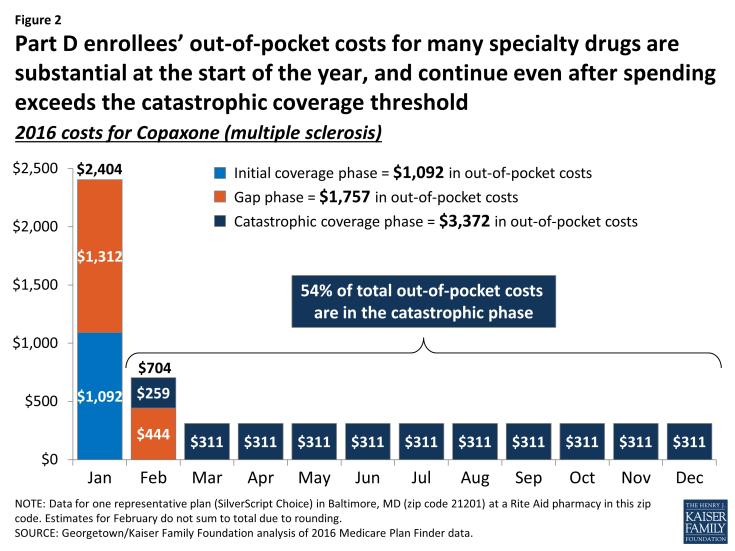

The most significant driver of out-of-pocket costs for a specialty drug, given the extraordinarily high cost of these drugs, is whether or not the drug is on formulary. Six of the 12 specialty drugs included in this study are on formulary in all plans—including two of the three hepatitis C drugs and all three of the cancer drugs (Figure 3). Cancer drugs are required to be on formulary by CMS guidance as one of six protected classes. Plans are also required to include at least two drugs on formulary in every category or class. Although the drugs in this study are not the only drugs in their drug classes, this requirement is a key factor in formulary design decisions.

The other six specialty drugs in this study are off formulary in at least four PDPs, including all three of the drugs used to treat multiple sclerosis (MS). Although all 20 PDPs include at least one of the three studied MS drugs on formulary (there are other treatments for MS as well), 14 PDPs include just one of the three MS drugs. Plans omit drugs from their formularies for a variety of reasons, and they must use their pharmacy and therapeutics committee to incorporate clinical considerations in their decisions. A key reason for exclusion is price negotiation: plans reportedly get the deepest discounts from a manufacturer when competing drugs are excluded from the plan’s formulary.

The cost to the beneficiary when a specialty drug is off formulary is nearly ten times higher—or more—than the median cost when on formulary (Table 1). This represents an added out-of-pocket cost, from nearly $40,000 (for Orencia or Enbrel) to nearly $90,000 (for Viekira Pak).

| Table 1: Part D enrollees’ out-of-pocket costs for specialty drugs vary significantly depending on their formulary coverage status | ||

| Drug | Median cost when listed on formulary in 2016 | Median cost when not listed on formulary in 2016 |

| Viekira Pak (hepatitis C) | $6,516 (n=2) | $95,818 (n=18) |

| Avonex (multiple sclerosis) | $5,979 (n=6) | $73,645 (n=14) |

| Copaxone (multiple sclerosis) | $6,448 (n=16) | $84,337 (n=4) |

| Tecfidera (multiple sclerosis) | $6,235 (n=8) | $79,886 (n=12) |

| Orencia (rheumatoid arthritis) | $4,413 (n=7) | $44,218 (n=13) |

| Enbrel (rheumatoid arthritis) | $4,872 (n=12) | $48,298 (n=8) |

| NOTE: Analysis includes 20 national and near-national stand-alone prescription drug plans in Baltimore, MD (zip code 21201) and reflects pricing at a Rite Aid pharmacy in this zip code. ‘n’ indicates number of plans listing or not listing each drug on formulary. Six other specialty drugs in this analysis not shown because they are on formulary in all plans (n=20).

SOURCE: Georgetown/Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2016 Medicare Plan Finder data. |

||

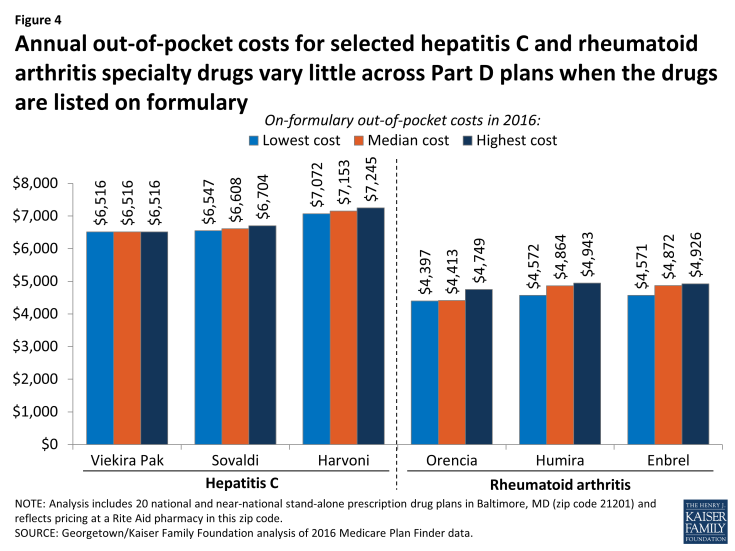

Out-of-pocket costs for specialty drugs tend to be similar across Part D plans, when on formulary, and are typically subject to prior authorization

For these 12 specialty drugs, the maximum out-of-pocket cost in PDPs listing the drug on formulary is never more than 10 percent higher than the minimum out-of-pocket cost. The out-of-pocket cost for Harvoni, the most common treatment for hepatitis C, ranges from $7,072 to $7,245, a difference of only 2 percent (Figure 4). The cost of Enbrel, the most commonly prescribed treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, ranges from $4,571 to $4,926 when on formulary, a difference of 8 percent. The pattern for the two drug classes shown in Figure 4 is comparable to the other two drug classes in this study.

Figure 4: Annual out-of-pocket costs for selected hepatitis C and rheumatoid arthritis specialty drugs vary little across Part D plans when the drugs are listed on formulary

While plans differ in setting specialty-tier coinsurance in the initial coverage phase at rates ranging from 25 percent to 33 percent, the vast majority of total costs to the consumers taking specialty drugs is established by law and does not vary by much across plans. This is because the different coinsurance rates apply only in the initial coverage period, and the majority of costs incurred by consumers occur in the coverage gap and catastrophic phases where cost sharing is set by law.2

When included on plans’ formularies, 11 of the 12 specialty drugs included in this analysis are always covered on the specialty tier. One of the 12 drugs—Orencia, for rheumatoid arthritis—is covered on a non-preferred brand tier by the two PDPs offered by UnitedHealth. This placement results in higher enrollee cost sharing in the initial coverage period than if the drugs were on the specialty tier, because the coinsurance for non-preferred brand drugs in these two plans is higher than for specialty drugs: 40 percent in the AARP MedicareRx Saver Plus PDP and 50 percent in the AARP MedicareRx Preferred PDP (in pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing, these amounts are 30 percent and 40 percent, respectively).

Specialty drugs are regularly subject to prior authorization and quantity limits. For eight of the 12 specialty drugs studied, all plans that list these drugs on formulary also require prior authorization, and most plans do the same for the other four drugs (Copaxone, Orencia, Enbrel, and Zytiga). In only two cases do plans require step therapy for these specialty drugs: one plan for Orencia and another plan for Tecfidera. (See Appendix Table 2 for drug-specific tier placement and utilization management information.)

Monthly out-of-pocket costs for commonly used brand and generic drugs tend to vary widely across Part D plans, even when included on plan formularies; for five of ten top brands, monthly costs vary by as much as $100 across plans

Top Brand Drugs

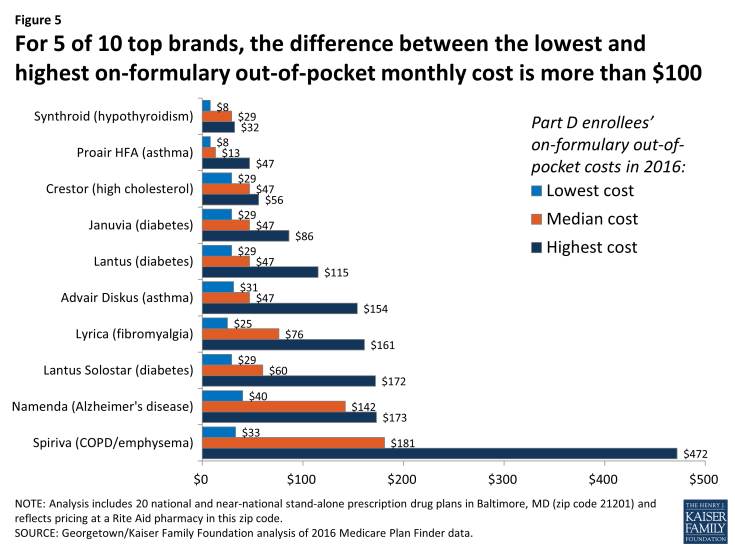

Cost sharing for a 30-day supply of ten commonly prescribed brand drugs can be anywhere from two to 14 times higher in one PDP versus another (Figure 5). For example, Namenda (a drug used by people with Alzheimer’s disease with a typical price of $345) has median monthly cost sharing of $142 in 2016, but an enrollee in Aetna Medicare Rx Saver PDP or First Health Part D Value Plus PDP pays only $40, whereas an enrollee in WellCare Classic PDP pays $173. (See Appendix Table 1 for drug-specific cost information.)

Figure 5: For 5 of 10 top brands, the difference between the lowest and highest on-formulary out-of-pocket monthly cost is more than $100

Compared to specialty drugs, total out-of-pocket costs are more heavily driven by how plans structure their benefits and formularies. Differences across plans in out-of-pocket costs for enrollees are driven by three factors: (1) tier placement (typically, two tiers for generics and two tiers for brands), (2) cost-sharing amounts assigned to the tiers by plans, and (3) whether cost sharing is structured as copayments or coinsurance (mostly coinsurance for non-preferred brands, mixed for preferred brands). Most brand drugs not on the specialty tier are not costly enough by themselves to force the beneficiary into the catastrophic coverage phase.

The impact of benefit design variations is illustrated by the drug with the greatest range in cost sharing (including only PDPs where the drug is on formulary). The cost to the consumer of Spiriva, a drug used to treat emphysema or COPD with a typical price of $950, ranges from $33 to $472 per month in 2016. The highest cost sharing for this drug ($472) is for a PDP that places the drug on a non-preferred brand tier with 50 percent coinsurance. The lowest cost sharing ($33) is for a PDP with a flat copayment amount for a preferred brand tier. In PDPs that place Spiriva on a preferred brand tier with coinsurance for a preferred brand tier, the cost to the consumer is also high, ranging from $153 to $245 depending mostly on variations in the coinsurance percentage, but also in the retail price of the drug.

By contrast, the smallest range in cost sharing ($29 to $56) is for Crestor (for high cholesterol), a drug with a price of about $220 per month. The small range in cost sharing for Crestor partially reflects pricing at a level where coinsurance typically matches the copayments. In general, any brand drug priced higher than $200 per month has higher out-of-pocket costs in PDPs that use coinsurance rather than a copayment. Thus, copayments for Crestor range from $29 to $47 and PDPs with coinsurance charge from $35 to $56.

For a less expensive brand drug such as ProAir (a treatment for asthma priced just over $50), consumers face lower costs when plans use coinsurance. Based on the relatively low price of this drug, PDPs with coinsurance charge their enrollees from $8 to $13 per month, while PDPs with copays charge from $33 to $47.

In most cases, plan enrollees pay more when the drug is on a non-preferred tier as opposed to a preferred tier. But there are exceptions. Synthroid (for hypothyroidism) is typically priced at about $32 per month. For five PDPs that place the drug on a non-preferred brand tier with coinsurance, enrollees pay between $14 and $17 per month in 2016. By contrast, seven PDPs with preferred brand tier use copayments that exceed the price of this drug; thus, the enrollee pays the entire cost of the drug—about $32.

Top Generic Drugs

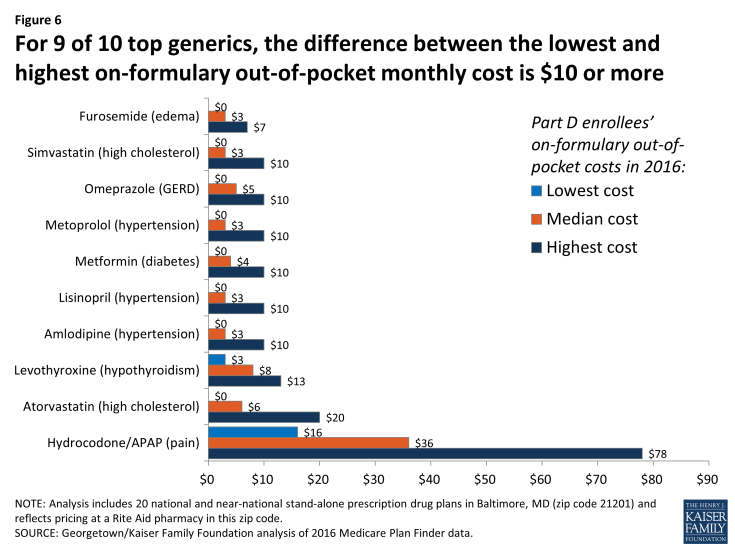

The range in out-of-pocket costs across Part D plans for a 30-day supply for ten top generic drugs tends to be much narrower than for brands (Figure 6). Most Part D enrollees who use the ten top generic drugs pay no more than $10 per month in cost sharing in 2016. The median cost sharing for all but one of these ten generics is between $3 and $8. Four of the top generics (furosemide, lisinopril, metformin, and metoprolol) are preferred generics for all 20 PDPs with a median copay of $3 or $4 and can be obtained for a zero copayment in some PDPs.

Figure 6: For 9 of 10 top generics, the difference between the lowest and highest on-formulary out-of-pocket monthly cost is $10 or more

However, in some cases, the differences in costs across plans are greater. Among the ten generic drugs included in this analysis, hydrocodone/APAP, an opioid used for pain relief, is covered by most plans as if it were a brand drug, which leads to higher costs for enrollees. Hydrocodone/APAP is placed on a brand tier for eight of the ten PDPs that have it on formulary. As a result, cost sharing in these ten PDPs is much higher than other generics, varying from $16 to $78 in 2016. (The full price for a month’s supply of hydrocodone/APAP also varies, ranging from $94 to $184 for the PDPs that have it on formulary.)

The two generic statins used to treat high cholesterol are treated somewhat differently. Atorvastatin has a median monthly copayment of $7 as result of being on the non-preferred generic tier on 12 of 20 PDPs (and on the non-preferred brand tier for 1 PDP). Simvastatin is a preferred generic for 17 of 20 PDPs and has a median copayment of $4. But, regardless of the PDP selected, either one of these generic drugs is less expensive for beneficiaries than the brand statin (Crestor), which has cost sharing of $29 to $56.

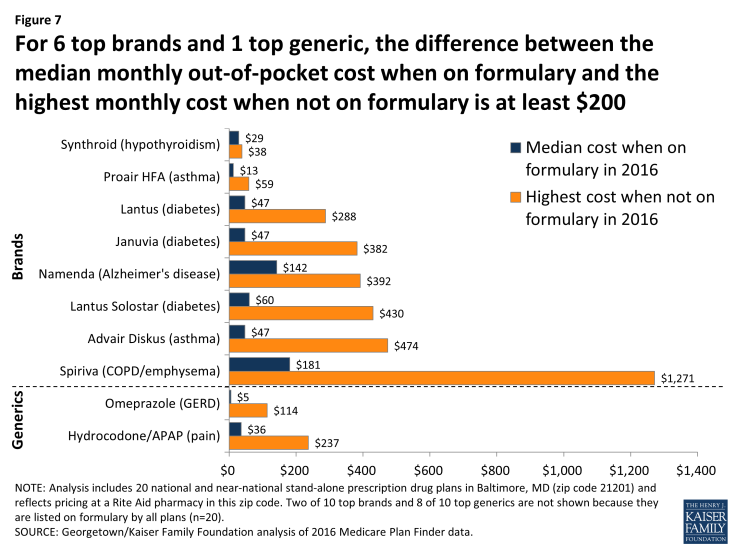

Out-of-pocket costs for commonly used brand and generic drugs are often significantly higher when they are off formulary than when they are on formulary; for six top brands and one top generic drug, costs are at least $200 more per month when off formulary than the median cost on formulary

Most (but not all) generics are on formulary for all PDPs, whereas many brand drugs are off formulary for a subset of PDPs. Eight of the ten top generic drugs in this study are always on formulary in 2016; hydrocodone/APAP is off formulary for 10 of 20 PDPs, and omeprazole is off formulary for 1 PDP. Just two of the ten top brands in this study are always on formulary. The remaining eight brands are off formulary for as few as 3 PDPs and as many as 7 PDPs of the 20 PDPs in this study.

Beneficiaries can face considerable costs for brands and for some generics when their drug is not listed on the plan’s formulary. For six of the top brands and one generic, the difference between median out-of-pocket cost when a drug is on formulary and the highest off-formulary cost is at least $200 per month in 2016 (Figure 7). A beneficiary with Alzheimer’s disease who takes Namenda will pay $392 per month in the five PDPs that leave this drug off formulary, compared to median cost sharing of $142. A beneficiary using Januvia to treat diabetes will see out-of-pocket costs increasing from $47 to $382.

Figure 7: For 6 top brands and 1 top generic, the difference between the median monthly out-of-pocket cost when on formulary and the highest monthly cost when not on formulary is at least $200

Even generic drugs can be expensive when off formulary. Beneficiaries may pay up to $114 for a month’s supply of omeprazole, compared to a monthly copayment of $5. Similarly, the price of hydrocodone/APAP is as high as $237 instead of a typical monthly copayment of $36.

Access to some drugs may be further influenced by utilization management restrictions, although these restrictions are applied less frequently for brands and generics than for specialty drugs. Two of the ten top brands in this study have prior authorization requirements in 2016. Six PDPs apply prior authorization to Lyrica, a treatment for nerve and muscular pain, and 13 PDPs have prior authorization requirements for Namenda, a drug used for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Several drugs also have step therapy requirements: Lyrica (one PDP), Januvia (two PDPs), and both versions of Lantus (one PDP). In addition, one PDP has a step therapy requirement for two generic drugs (atorvastatin and hydrocodone/APAP). (See Appendix Table 2 for drug-specific tier placement and utilization management information.)

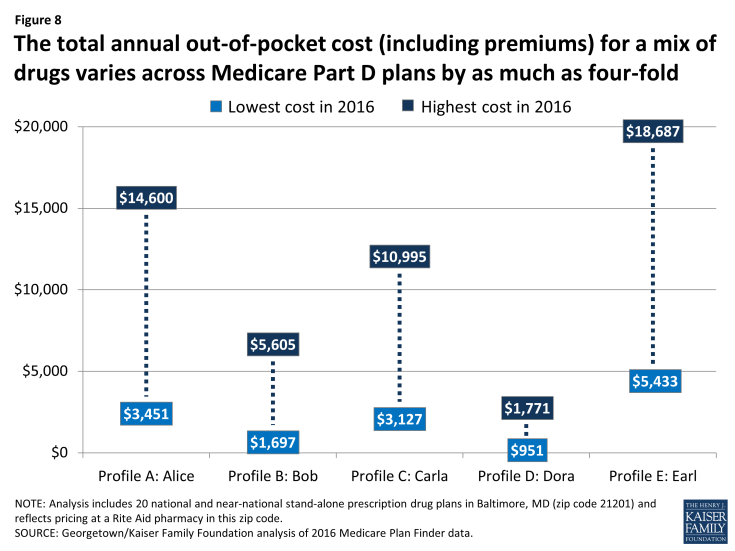

Based on five hypothetical beneficiaries taking a mix of medications for multiple conditions, total out-of-pocket costs vary by as much as four-fold across Part D plans, taking into account the number and type of drugs they take, whether or not their drugs are on formulary, cost-sharing amounts, and monthly premiums

Few Medicare beneficiaries take only one drug, and for those who use the Medicare Plan Finder, the total out-of-pocket costs displayed reflect costs for the full array of drugs they take throughout the year along with plan premiums and deductibles, if applicable. Total out-of-pocket costs—cost sharing for all drugs and premiums—for five hypothetical beneficiaries who take at least five medications for various health conditions differ by at least $800 across 20 PDPs available in a given area in 2016 (Figure 8). Alice (Profile A), who takes six drugs for conditions that include asthma and diabetes, would spend $3,451 out of pocket if she enrolls in the SilverScript Choice PDP, whereas it would cost her $14,600 if she enrolls in Transamerica MedicareRx Classic PDP. The contrast is considerably less for Dora (Profile D) who takes five generic drugs for diabetes, hypertension, and three other conditions. Her annual costs would be $951 in the AARP Medicare Rx Saver Plus PDP, compared to $1,771 in the Humana Enhanced PDP.

Figure 8: The total annual out-of-pocket cost (including premiums) for a mix of drugs varies across Medicare Part D plans by as much as four-fold

The wide variation in out-of-pocket costs across Part D plans is due to several factors, including whether the beneficiary’s drugs are on or off formulary, each drug’s placement on a cost-sharing tier, the different cost-sharing amounts associated with each tier, whether cost sharing is structured as coinsurance or copayments, and plan premium amounts. Total costs vary less for Dora because her five generic drugs are all on formulary for the 20 PDPs in this study. For a beneficiary such as Alice who takes drugs that are not always on formulary (in her case, two of six drugs are off formulary in some PDPs), total costs are as much as $10,000 higher.

But even when all of their drugs are on formulary, total out-of-pocket costs across all PDPs can still vary substantially (Table 2). Bob (Profile B) takes five drugs for Alzheimer’s disease and other conditions. His drugs are all on formulary for 19 of 20 PDPs; yet his costs for those plans range from $1,697 (AARP Medicare Rx Saver Plus PDP) to $3,349 (SilverScript Plus PDP). Premium differences ($34 versus $87 in this example) tend to be a greater factor in cost differences when comparing plans that have all drugs on formulary.

Earl (Profile E) has multiple chronic conditions for which he takes 13 drugs, including 9 brand drugs (but no specialty-tier drugs). His out-of-pocket costs add up to $5,433 even in the least expensive plan for his situation (Humana Enhanced PDP), but can be as much as $18,687 in a plan (Transamerica MedicareRx Classic PDP) where four of his drugs off formulary. Notably, the least expensive plan for Earl is the most expensive plan for Dora, illustrating how much costs can vary based on individual needs. Earl’s costs, even in the least expensive plan for him, put him over the catastrophic threshold. Like beneficiaries who take a single specialty drug, a large share (37 percent) of Earl’s total out-of-pocket drug costs occur while he is in the catastrophic phase.

| Table 2: The total annual out-of-pocket cost for Part D enrollees taking a varying mix of medications to treat multiple conditions ranges up to four-fold in 2016 | |||||

| Profile A: Alice | Profile B: Bob | Profile C: Carla | Profile D: Dora | Profile E: Earl | |

| Conditions | Asthma

Diabetes High cholesterol Hypertension |

Alzheimer’s

Edema High cholesterol Overactive bladder |

Hypertension

Hypothyroidism Insomnia Migraines Pain |

Diabetes

High cholesterol Hypertension Hypothyroidism Osteoporosis |

Alzheimer’s

Asthma Diabetes High cholesterol Hypertension Hypothyroidism Insomnia Overactive bladder Pain Schizophrenia |

| Medications | n=6:

Advair Diskus Amlodipine Crestor Januvia Lantus Solostar Metformin |

n=5:

Atorvastatin Donepezil Furosemide Namenda XR Oxybutynin |

n=5:

Eszopiclone Lyrica Sumatriptan SPR Synthroid Valsartan/HCTZ |

n=5:

Atorvastatin Levothyroxine Metformin Metoprolol Succinate ER Raloxifene |

n=13:

Crestor Eszopiclone Januvia Lantus Solostar Latuda Lyrica Metformin Metoprolol Succinate ER Namenda XR Rivastigmine Symbicort Synthroid Vesicare |

| Brand/generic mix | 4 brands

2 generics |

1 brands

4 generics |

2 brands

3 generics |

0 brands

5 generics |

9 brands

4 generics |

| Number of plans: | |||||

|

13 | 19 | 3 | 20 | 2 |

|

4 | 1 | 12 | N/A | 5 |

|

3 | N/A | 5 | N/A | 13 |

| Range in out-of-pocket costs: | |||||

|

Low: $3,451

High: $4,157 |

Low: $1,697

High: $3,349 |

Low: $3,12

High: $4,195 |

Low: $951

High: $1,771 |

Low: $5,433

High: $5,529 |

|

Low: $7,846

High: $9,154 |

$5,605 | Low: $6,826

High: $8,025 |

N/A | Low: $5,475

High: $9,828 |

|

Low: $13,629

High: $14,600 |

N/A | Low: $7,645

High: $10,995 |

N/A | Low: $9,363

High: $18,687 |

| NOTE: Analysis includes 20 national and near-national stand-alone prescription drug plans in Baltimore, MD (zip code 21201) and reflects standard pharmacy pricing at a Rite Aid pharmacy in this zip code. Total out-of-pocket costs include medication costs and monthly plan premiums. ‘n’ indicates total number of drugs in each profile. ‘N/A’ indicates not applicable.

SOURCE: Georgetown/Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2016 Medicare Plan Finder data. |

|||||

Pharmacy choice can affect total out-of-pocket costs, and pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing can provide savings, but the magnitude of savings varies by plan, pharmacy, and the mix of drugs

There is some variation in out-of-pocket costs by pharmacy—driven by plans’ use of tiered pharmacy networks, by pricing differences across pharmacies, and by the availability of mail order. The recent trend toward greater use of tiered pharmacy networks has raised the issue of pharmacy choice as another factor for enrollees to consider in comparing plans. Under these arrangements, plans make preferred cost sharing available at a limited number of network pharmacies and higher (standard) cost sharing at other network pharmacies.

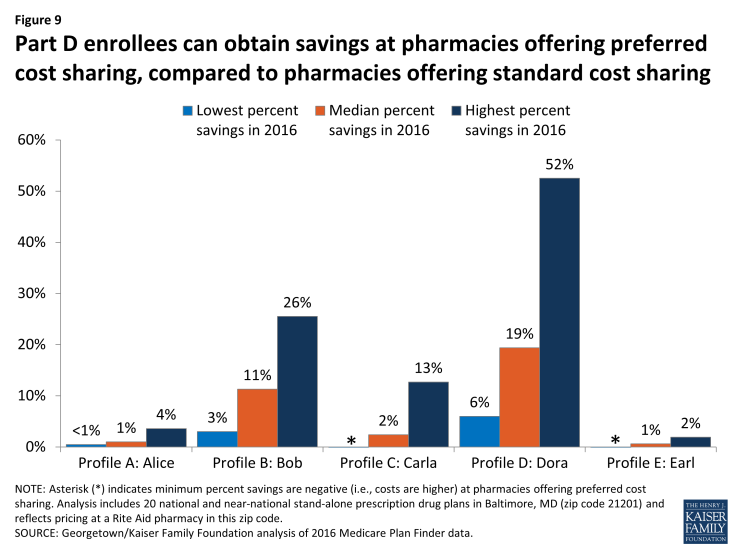

For three of our five hypothetical beneficiaries (Alice, Carla, and Earl), the typical (median) savings achieved by using a pharmacy with preferred cost sharing is less than 3 percent in 2016—measured across 13 PDPs with a nearby pharmacy that offers preferred cost sharing (Figure 9). For the other two hypothetical beneficiaries, the median savings for using a pharmacy with preferred cost sharing is greater: 11 percent for Bob and 19 percent for Dora.

Figure 9: Part D enrollees can obtain savings at pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing, compared to pharmacies offering standard cost sharing

Savings from pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing can be substantial, especially for drug profiles that are more heavily reliant on generics, but can be quite modest when most drugs are brands. This is because plans that use tiered pharmacy networks typically reduce cost-sharing amounts more for generic drugs than for brands, perhaps because pharmacies have more leverage over discounts for generic drugs.3 For example, cost sharing for generics can drop from $10 down to $1 or even $0 at pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing.

Alice and Earl have the highest overall out-of-pocket costs for the drugs they take—largely because they are more reliant on brand drugs than the three other hypothetical beneficiaries. But they have the smallest rate of savings from using a pharmacy with preferred cost sharing (Table 3). In dollar terms, they have the potential to save less than $200 based on their chosen pharmacy in 2016—a small amount for a set of drugs that cost them at least $3,000 out of pocket. From a beneficiary’s perspective, the selection of a pharmacy or the selection of a plan based on the pharmacy they typically use is more important, in terms of savings, if they take a lot of generic drugs.

| Table 3: Total annual out-of-pocket costs for Part D enrollees taking a varying mix of medications to treat multiple conditions are modestly lower in pharmacies offering preferred cost sharing in 2016 | |||||

| Profile A: Alice | Profile B: Bob | Profile C: Carla | Profile D: Dora | Profile E: Earl | |

| Brand/generic mix | 4 brands

2 generics |

1 brands

4 generics |

2 brands

3 generics |

0 brands

5 generics |

9 brands

4 generics |

| Range in out-of-pocket costs: | |||||

|

Low: $3,575

High: $14,600 |

Low: $1,697

High: $5,605 |

Low: $3,127

High: $8,025 |

Low: $951

High: $1,771 |

Low: $5,433

High: $18,687 |

|

Low: $3,445

High: $14,442 |

Low: $1,457

High: $5,438 |

Low: $3,028

High: $7,748 |

Low: $533

High: $1,564 |

Low: $5,438

High: $18,581 |

| NOTE: Analysis includes 13 national and near-national stand-alone prescription drug plans in Baltimore, MD (zip code 21201) where a pharmacy with preferred cost sharing is available in this zip code. Total out-of-pocket costs include medication costs and monthly plan premiums.

SOURCE: Georgetown/Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2016 Medicare Plan Finder data. |

|||||

Mail order can also offer some savings to enrollees, compared to retail pharmacies, but not for all PDPs. Mail order savings are greater when compared to pharmacies with standard cost sharing (versus preferred cost sharing); all five of our hypothetical beneficiaries save money using mail order compared to retail for most PDPs when the chosen retail pharmacy is one that uses standard cost sharing (Table 4). In many cases, however, the savings are less than 10 percent. Out-of-pocket costs for mail order are closer to costs at retail pharmacies with preferred cost sharing. In fact, for some PDPs, out-of-pocket costs are higher for mail order than for a retail pharmacy with preferred cost sharing.

| Table 4: Some Part D plans offer savings for drugs purchased through mail order rather than retail pharmacies | ||||

| Profile | Pricing for mail order compared to retail pharmacies with standard cost sharing | Pricing for mail order compared to retail pharmacies with preferred cost sharing | ||

| Number of plans where mail order pricing is less expensive in 2016 | Number of plans where mail order pricing is more expensive in 2016 | Number of plans where mail order pricing is less expensive in 2016 | Number of plans where mail order pricing is more expensive in 2016 | |

| Profile A: Alice | 20 | 0 | 10 | 3 |

| Profile B: Bob | 16 | 4 | 9 | 4 |

| Profile C: Carla | 17 | 3 | 7 | 6 |

| Profile D: Dora | 19 | 1 | 8 | 5 |

| Profile E: Earl | 20 | 0 | 13 | 0 |

| NOTE: Analysis includes 20 national and near-national stand-alone prescription drug plans in Baltimore, MD (zip code 21201) and reflects pricing at a Rite Aid pharmacy in this zip code.

SOURCE: Georgetown/Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 2016 Medicare Plan Finder data. |

||||

Discussion

This analysis shows that out-of-pocket costs can exceed thousands of dollars for beneficiaries who take just one specialty drug or a large number of less costly brands and generics. In 2014, 2 percent of Part D enrollees used specialty tier drugs, though not all enrollees who use these drugs will face out-of-pocket costs as high as those identified in this analysis.4 Out-of-pocket costs would be lower for enrollees who receive the Low-Income Subsidy and for enrollees who take specialty drugs that are less expensive than the drugs we analyzed.

Even with catastrophic coverage, Part D enrollees are exposed to high costs because the catastrophic coverage threshold is not a hard cap on out-of-pocket costs. In extreme situations, enrollees pay more money after reaching the catastrophic phase of the benefit than before it. Policymakers could strengthen financial protections for beneficiaries with significant drug costs by making the current catastrophic coverage threshold an absolute limit.

The highest costs occur when a prescribed drug is off formulary. Beneficiaries in this situation have the option to consult with their prescriber about therapeutic alternatives and get a different prescription if appropriate, or request an exception. Or they can try to obtain the drug through a source such as a manufacturer’s patient assistance program. Such programs, however, may require meeting income eligibility standards, and they must operate independently of the Part D program.

If the need for a new drug can wait until the first of the following year, after the open enrollment period, the high cost of specialty drugs, and even some brands, creates a strong incentive to enroll in a plan that has their drug on formulary. When a new drug is prescribed midyear, however, this delay may come with serious clinical consequences. Neither a new prescription for a drug that is off formulary nor a newly diagnosed health condition creates the basis for a midyear special enrollment period.

With median income among Medicare beneficiaries at about $24,000 per person, the cost of off-formulary specialty and other high-priced drugs is beyond the reach of many Part D enrollees.5 Some might be able to pay directly for off-formulary drugs out of pocket, but if they do, their costs will not count towards reaching their benefit phases, including the catastrophic threshold. Individual purchasers do not benefit from the manufacturer discounts that are available to plan purchasers in the form of post-invoice rebates paid by manufacturers to plans and kept confidential.

The Medicare Plan Finder can be a powerful tool to allow enrollees to predict total annual out-of-pocket costs across plans in their area, based on the drugs they take. Even so, the Plan Finder has inherent limitations. Beneficiaries can use the Plan Finder to search for plans based on drugs they are currently taking, but they cannot factor in their search the cost of a new prescription that comes after the enrollment period has ended. Nor can the Plan Finder easily show the beneficiary others ways to obtain a drug or what therapeutic alternatives are available. Furthermore, when a drug is off formulary, the price displayed may not reflect the actual price a beneficiary sees at the pharmacy.

Choice of plans matters in Part D. Beneficiaries’ health conditions and medication needs continually change, and plans often make changes in their formularies and cost sharing from one year to the next. The Plan Finder allows beneficiaries to compare plans during the open enrollment period, taking into account their current drugs and plan benefit designs for the coming year. A concise and personalized notice to enrollees describing how plan changes will affect them in the coming year might be one way to convince more to shop during the open enrollment period.

Our analysis shows that Part D enrollees can benefit from careful plan comparisons, looking not just at premiums, but also at formulary coverage and tier placement of their drugs, and at how their pharmacy is treated by plans. Yet while it pays to shop, most people do not switch plans during the open enrollment period.6,7 As a result, many Part D enrollees leave money on the table—sometimes thousands of dollars.