Impact of Shifting Immigration Policy on Medicaid Enrollment and Utilization of Care among Health Center Patients

Introduction

Since taking office, the Trump Administration has implemented a range of policy changes focused on enhancing immigration enforcement and limiting immigration. Most recently, on August 14, 2019, the administration published a final rule to change “public charge” policies that govern how the use of public benefits may affect individuals’ ability to enter the U.S. or adjust to legal permanent resident (LPR) status (i.e., obtain a “green card”). The rule, which was proposed in October 2018, broadens the programs that the federal government will consider in public charge determinations to include previously excluded health, nutrition, and housing programs, including Medicaid coverage for non-pregnant adults for a wide range of health care needs. The rule will likely lead to decreased enrollment in Medicaid, CHIP, and other programs broadly among immigrant families, beyond individuals directly impacted by the rule. Prior to this final rule, there were growing reports of individuals disenrolling or choosing not to enroll themselves or their children in Medicaid and CHIP due to growing fears and uncertainty stemming from the shifting immigration policy environment.1 The final rule was scheduled to go into effect on October 15, 2019, but on October 11th a nationwide preliminary injunction was issued, blocking implementation.

Community health centers are often on the front lines of policy changes affecting Medicaid coverage. They serve a diverse, predominantly low-income patient population, including low-income immigrants in many communities, and nearly three-quarters of health center patients are covered by Medicaid or are uninsured. Given their role serving immigrant families, the experiences of health centers and their patients can provide early insight into the potential effects the public charge rule and other immigration policies are having on health coverage and use of services by immigrant patients.

To learn about these possible early effects, this brief draws on interviews and survey data to capture health center directors’ and staff’s perceptions of changes in coverage and service use among patients who are immigrants. It relies on interviews with 16 directors and senior staff at health centers in four states—California, Massachusetts, Missouri, and New York– conducted in September 2019, after the final public charge rule was issued. The interviews asked about perceived trends in health coverage of immigrant patients and their families as well as changes in utilization of health care and social services. It also includes results from the 2019 KFF/George Washington University Community Health Center Survey about perceived changes in Medicaid enrollment and health care use among immigrant patients and their families. The survey of staff from 511 health centers was fielded from May through July 2019, after the administration had released the proposed rule to make changes to public charge policy but prior to it being finalized.

Key Findings

Changes in Medicaid Enrollment

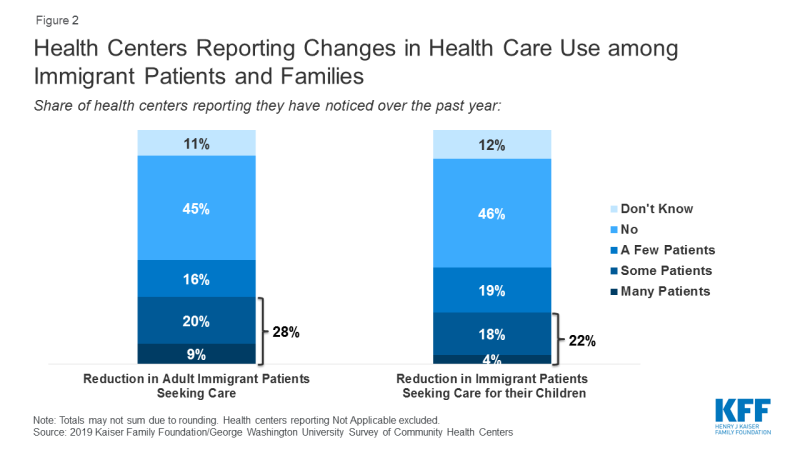

Based on findings from the health center survey, nearly half (47%) of health centers reported that many or some immigrant patients declined to enroll themselves in Medicaid in the past year (Figure 1). In addition, nearly one-third (32%) said that many or some immigrant patients disenrolled from or declined to renew Medicaid coverage. Health centers also report enrollment declines among children in immigrant families. More than a third of (38%) health centers reported that many or some immigrant patients were declining to enroll their children in Medicaid over the past year, while nearly three in ten (28%) reported many or some immigrant patients were disenrolling or deciding not to renew Medicaid coverage for their children.

Figure 1: Health Centers Reporting Changes in Medicaid Enrollment among Immigrant Patients and Families

Follow-up interviews with health center staff are consistent with these survey findings of declining Medicaid enrollment among immigrant patients and their families. Staff at all health centers reported that, in recent months, immigrant patients have declined to enroll or reenroll themselves and/or their children in Medicaid. Health centers do not collect data on immigration status of patients, so these observations (as well as the survey results) are based on health centers’ perceptions of who they believe to be immigrant families using available information. Immigrant families generally view health center staff as a trusted resource, and in turn, are willing to discuss their immigration status with these staff and clinicians. In addition, enrollment staff who assist patient in applying for Medicaid and other coverage have access to this information as part of the application process. At some health centers interviewed, these changes were widespread with many patients dropping Medicaid while at others, the changes were occurring among only a small number of patients. Health center directors at two health centers cited shifts in their payer mix data, with the share of uninsured health center patients increasing, as possible evidence of these changes. Others cited data and information reported by frontline enrollment staff. Even health center directors who noted few patients at their health centers were dropping coverage recounted conversations they had with patients who declined to enroll in Medicaid. Health centers serving smaller shares of immigrant patients were more likely to report that only a few patients were choosing not enroll in Medicaid.

Our patient navigation team which is multilingual and multiethnic used to work with upwards of 10 people a day to get them signed up for coverage… men, women, children, etc. Now they’re down to 2 to 3 clients a day if they’re lucky. (Health Center CEO, MO)

Our insurance companies… we have Healthfirst at all of our sites to enroll folks. And they’re seeing that folks aren’t re-enrolling. They’re actually coming up to our sites to do a public charge information session for all the folks because they’re seeing disenrollments. (Health Center President, NY)

We had one lady who came in and she said, ‘I’m going to apply for my children because they are citizens, but I’m not, so I am not going to apply.’ (Intake/Outreach Supervisor, MA)

According to health center interview respondents, immigrant patients are confused by the new rules and many are receiving misinformation. All respondents reported confusion among their immigrant patients over new the new rules. They said patients are asking questions of health center staff and noted that many patients are not sure which programs the new rules apply to and who is subject to them. Based on reports from patients and their own conversations with advocates and the legal community, several health center directors noted that some of the confusion stems from some immigration lawyers advising clients to avoid all public programs and services out of an abundance of caution. At the same time, they also said rumors and misinformation spread quickly through communities. For example, a health center director in California recounted how misinformation was quickly spread through WeChat, a social media and messaging app which is commonly used in the predominantly Asian immigrant community served by the health center.

What we have heard from our staff on the front line, the folks who interface with our patients around the enrollment, they are hearing that people are afraid around disclosing more information about their families who would not even be impacted, but because there’s a lot of misinformation out in the community… they’re not clear in terms of how that’s going to impact them. (Health Center Compliance Officer, CA)

Health center respondents reported that immigrant patients are increasingly afraid to disclose personal information. Interview respondents across all health centers reported that some immigrant patients have become reluctant to disclose any personal information out of fear that the health center would share that information with authorities. This information is necessary not only to assess eligibility for Medicaid and other federal programs, but also for state and local social services programs. According to respondents, the fear stems from multiple sources—fear of deportation among immigrants who lack legal status and fear that sharing any information could jeopardize their or a family member’s efforts to obtain a green card or citizenship.

The reason provided is fear and uncertainty related to immigration and customs enforcement agents potentially showing up and carting them away as they enter or leave the building or the federal government getting the information they provide us. (Health Center President, MO)

People are not generally going to feel comfortable providing their name and information, so we’re going to be thoughtful about how we collect that information from our patients, so that we’re not also making them afraid to give information about their own status – we’ll serve them regardless. (Health Center CEO, CA)

Health center interview respondents reported that the patients disenrolling or declining to enroll in Medicaid are a broader group of immigrants than those targeted by the public charge rule. Health center respondents reported that some patients declining to enroll in Medicaid already have Lawful Permanent Status (LPR), and therefore would not be subject to the new public charge rule. They noted these decisions may stem from fear that the patients will lose their current lawful status or that they may be barred from applying for citizenship if they receive any services. Another explanation offered is that these patients are concerned that they will jeopardize the safety or status of a family member. Respondents also reported that patients have expressed concerns that enrolling their children in these programs, even if their children were born in the United States, may jeopardize their status or the status of family members. In addition, although pregnant women are categorically eligible for Medicaid and would be unaffected by public charge if they enroll in Medicaid, health center respondents reported that pregnant women are declining to enroll in Medicaid or disenrolling, in some cases out of fear of risking future opportunities for residency or citizenship.

Approximately 10% of those foreign born women who were pregnant will tell us they do not intend to, they do not want to apply for Medicaid… because they are afraid. Their fears range from being deported, to future opportunities for residency or citizenship. It’s a wide range of things they are afraid of, but ultimately it’s jeopardizing their status. (Health Center Vice President, MO)

Fear of public charge implications extends beyond Medicaid to other health and social service programs, including some that are not included in the public charge rule. In addition to helping patients enroll in Medicaid and other health coverage programs, most health centers also assist patients with enrollment in a range of social service programs, including food and housing assistance programs, job training programs, and education programs. Based on this enrollment assistance experience, some interview respondents reported immigrants are avoiding housing and food assistance programs. While the public charge rule includes some housing assistance programs and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), it does not include other key nutrition programs such as WIC and school lunch. A major concern among respondents was data suggesting that immigrant pregnant women are refusing WIC services. Several respondents noted that their WIC caseloads are down and attributed the trend to public charge fears. Respondents in California and Missouri also noted that immigrant patients are declining to enroll in or accept referrals for state and local food assistance programs, even though these programs are not subject to public charge. A health center serving New York City reported that patients with HIV or AIDS are hesitating to enroll in or are disenrolling from the city-run HIV/AIDS Services Administration (HASA) program out of fear that the program’s services fall under the public charge rule.

We began to see a decline in people coming in for their basic health screenings, for nutrition services. Even if they were hungry, they were not telling us, so we had to change. As we saw the WIC numbers [decline]… we started asking questions as part of their visit. (Health Center President, MA)

Changes in Health Care utilization

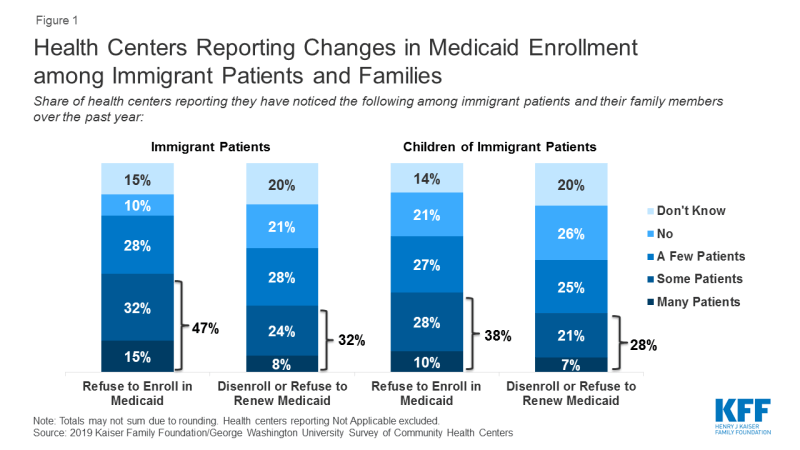

According to the survey, nearly three in ten (28%) health centers reported declines among many or some adult immigrant patients in seeking health care in the past year. Over one in five (22%) reported reductions in health care use among some or many children in immigrant families (Figure 2).

The findings from the interviews were consistent with findings from the health center survey about changing utilization among immigrant patients and their families. For example, health center directors in Massachusetts and Missouri described significant drops in utilization as evidenced by an increase in appointment cancellations and no shows by immigrant patients. Another health center director noted that, while their patient base remains strong, patient encounters have declined, so much so that their clinicians are working at only about 80% capacity. At the same time, other health center directors in Massachusetts and Missouri have observed little change in service use by their immigrant patients. A health center director in California said, while they are seeing utilization changes, it is too early to attribute those changes solely to the public charge rule and that other factors, including increased ICE enforcement activities, may be playing a role.

We are extremely worried about the trend we’ve noticed over the last 6-8 months, which is that people are afraid to keep their appointments, to sign up for appointments, to come into the buildings or the various clinical sites and fill out basic paperwork, or even provide their address or ID or other personal information. (Health Center President, MO)

Our overall number of patients we serve remains pretty steady. Our actual encounters have gone down… In the past, say 5 years ago, you couldn’t get an appointment because we were so packed. Now, I would say the majority doctors are 80 percent full. (Health Center President, CA)

Health center interview respondents reported that pregnant women are delaying prenatal care or seeking care less frequently. Nearly all respondents that provide obstetric care noted that immigrant pregnant women are initiating prenatal care later in their pregnancies. They indicated that efforts to educate pregnant women often are insufficient to overcome fears about enrollment and that many women continue to decline to enroll in Medicaid or access care even after being told they are exempt from the public charge rule. Respondents expressed particular concerns about the potential consequences of this trend on health outcomes, noting that it was eroding years of work and progress to encourage pregnant women to access prenatal care early in their pregnancies.

We have a seen a decline in our pregnant visits… insured or otherwise. When we drill down and actually talk to them – “Why did you wait until your sixth month to come in?” they say ,”Oh because I’m afraid.” (Health Center CEO, NY)

Health center directors reported that some of their patients with chronic conditions are foregoing care and others are not getting preventive care. In particular, respondents whose programs offer group sessions for diabetes patients noted a drop in participation in their Spanish-language group sessions. A health center in New York reported a decline in the use of PrEP among their immigrant patients at risk for exposure to HIV. Respondents also suggested that fear of using services may prevent patients with acute care needs from getting care. One respondent pointed out that, during the height of the flu season last winter, visits at an urgent care clinic in California dropped significantly and coincided with rumors related to the public charge rule spreading on social media.

One of the central tenets of diabetes care for example is that, in addition to managing the person’s medical condition, we do group education sessions for them to teach them how to shop healthy, eat healthy… that is critical to the health status outcomes to the diabetes patients. We have seen a steady drop in attendance and participation (Health Center CEO, MO)

This action [public charge] totally undermines the work that we’re trying to do around managing population health. I think when you’re really going to see it is around flu season. (Health Center CEO, CA)

Effects on health center patients, staff and operations

Health center interview respondents reported their staff are observing increased rates of anxiety and stress-related conditions among their immigrant patients. As a result, behavioral health counselors are getting more requests for counseling and therapy. Respondents also expressed significant worries about the effects on children, describing their pediatric patients as being traumatized by what is happening to their families and in their communities.

The children are terrified… One pediatrician relayed his conversation with a 7-year-old when the mother went outside to take a phone call. The child said, “Can you give something to my mother because she’s afraid all the time. She doesn’t want to let me out…” (Health Center CEO, NY)

Several respondents said they were implementing new protocols and services to ensure the highest need patients continue to receive care despite growing fears. A health center director in Massachusetts reported that case managers will contact the highest risk patients and will arrange for home visits and free delivery of medications if patients are too afraid to come to the clinic. A health center in New York serving a large migrant community sends staff out to farms in rural areas to deliver babies and treat injuries for patients who will not come to the health center or other providers out of fear of jeopardizing their ability to continue working in the US.

They had a person that was severely injured on the farm and they could not get him to go to the hospital because of the fear of going out there… (Health Center President, NY)

Nearly all health center interview respondents said they are training staff, starting with frontline staff, but working through the organization to include clinicians and others, to ensure they understand the new rules and can respond accurately to patient questions. Respondents operating large programs noted the difficulty associated with training all staff and worried about patients potentially getting conflicting information from different staff, which could possibly lead to an erosion of trust between the patient and the health center. At the same time, several respondents voiced concerns over the effect of the challenging environment facing immigrants on their staff, many of whom are immigrants themselves and live in the communities served by the health centers.

We can’t get information out fast enough to alleviate the fears. Just getting our own staff trained to understand all the nuances of this, it’s incredibly difficult. (Health Center President, CA)

Giving staff lists on what public benefits are impacted, frequently asked questions so they can orient both the patients and they can orient themselves on what they can tell our patients and not continue the fear and chill factor that we’re seeing. We’re also going to do trainings with our HSF folks, the frontline level staff so they feel comfortable responding to these questions. (Health Center Compliance Officer, CA)

Several health center interview respondents reported the decline in patients covered by Medicaid combined with an increase in the number of uninsured patients and an overall drop in patient visits has led to revenue losses. For some, the revenue declines have been manageable, but two respondents reported experiencing operating losses this year that they attribute to immigration policies. A respondent in Missouri noted that as patients drop Medicaid and move onto the sliding fee scale, they often struggle to make those payments, increasing financial pressures on the families and on the health center. Respondents were clear in noting that not all of these effects are attributable solely to the public charge and that there are multiple factors.

Because of what’s going on and the reluctance of people to sign up for Medicaid even when they are fully eligible… they are switching to self-pay. That means that percentage of self-pay is going up. That hits our bottom line. If the [percentage of] self-pay comes up to 50 percent, you know your health center is suffering financially… We’re not making enough to pay our own bills. (Health Center CEO, MO)

My revenue is down so significantly because… the lack of reenrollment for Medicaid benefits and uptick in uninsured visits is one-to-one. What we realized is that … patients are coming in, but they’re not coming in and using their Medicaid benefits. (Health Center CEO, NY)

Conclusion

Consistent with other recent research, these findings reporting the perceptions and experiences of community health centers suggest that shifting immigration policies are leading to decreased participation in Medicaid among some immigrant families and their children who use services at community health centers. Health center directors and staff reported that declines in Medicaid coverage are occurring broadly among immigrant patients and their children, beyond those targeted by the public charge rule and including those who are explicitly exempt, such as pregnant women. These findings also indicate that growing fear and uncertainty among immigrant families in response to shifting immigration policy are contributing to declines in health care use among some immigrant patients and their families, including among pregnant women. Decreased coverage and declines in health care use could have a negative impact on the health and well-being of families and children, and will likely have longer-term consequences. Moreover, these changes carry the potential for broader, community-wide implications as decreases in coverage increase financial strain on health centers, thereby adding to challenges to providing care.

|

Methods The findings in this brief are based on structured phone interviews with health center directors and senior staff conducted by Kaiser Family Foundation in four states: California, Massachusetts, Missouri, and New York. In total, we conducted interviews with 16 health centers across the four states—two each in California, Massachusetts, and Missouri, and ten in New York. Health centers were selected to represent a mix of characteristics, including location in urban vs. rural areas, size, and share of immigrant patients served. The health centers’ patient populations ranged in size from 15,000 – 91,000 total patients and estimates of immigrant patients served ranged from 10% to over 80%. The interviews were conducted in September 2019. The brief also reports findings from the 2019 Kaiser Family Foundation/George Washington University Survey of Community Health Centers. The survey was designed and analyzed by researchers at KFF and GWU, and conducted by the Geiger Gibson Program in Community Health Policy at GWU. It was fielded from May to July 2019 and was emailed to 1,342 CEOs of federally funded health centers in the 50 states and the District of Columbia identified in the 2017 Uniform Data System. The response rate was 38%, with 511 responses from 49 states and DC. Additional support for the survey was provided by the RCHN Community Health Foundation as part of its ongoing research collaborative with the Geiger Gibson Program. 2019 Survey of Community Health Centers (Questions 1-15 and 17-34 reserved for future release) Q16. Over the past year, has your health center noticed any of the following among your immigrant patients and their family members? Please indicate whether the following have been seen among many patients, some patients, a few patients, no patients, not applicable, or don’t know. Patients who refuse to enroll in Medicaid for themselves Patients who refuse to enroll in Medicaid for their children Patients who disenroll or refuse to renew their own Medicaid coverage Patients who disenroll or refuse to renew Medicaid coverage for their children A reduction in the number of adult patients seeking care from the health center A reduction in the number of patients seeking care for their children from the health center |