Health and Financial Risks for Noncitizen Immigrants due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a disproportionate toll on some groups of individuals, including lower income individuals and people of color. One group who faces risks and challenges associated with the pandemic is the nearly 22 million noncitizen immigrants living in the U.S. today. Non-citizen immigrants were already facing a range of challenges prior to the pandemic, including increased fear and uncertainty due to shifting immigration policy that was leading some to turn away from accessing programs and services. As virus hotspots have risen in the Southern and Western regions of the country, with reports of increases in towns along the U.S.-Mexico border, understanding the risks and challenges facing noncitizen immigrants is of increasing importance. This brief analyzes key characteristics of noncitizen immigrants to examine the health and economic risks they face amid the pandemic. It finds:

- Noncitizen immigrants are more likely to live in large households and in urban areas compared to citizens. Overall, 33% of noncitizen immigrants live in a household with more than four people compared to 21% of citizens. Noncitizens also are more likely than citizens are to live in an urban area (96% vs. 86%).

- There are nearly 13 million noncitizen immigrant workers who make up 8% of the overall workforce and are concentrated in jobs that cannot be done virtually. Nearly one in four (23%) noncitizen workers are in the construction and restaurant and food services industries. Occupations that employ the largest numbers of noncitizen workers include construction laborers, cooks, janitors and building cleaners, agricultural workers, and maids and housekeepers, where they also account for a high share of all workers.

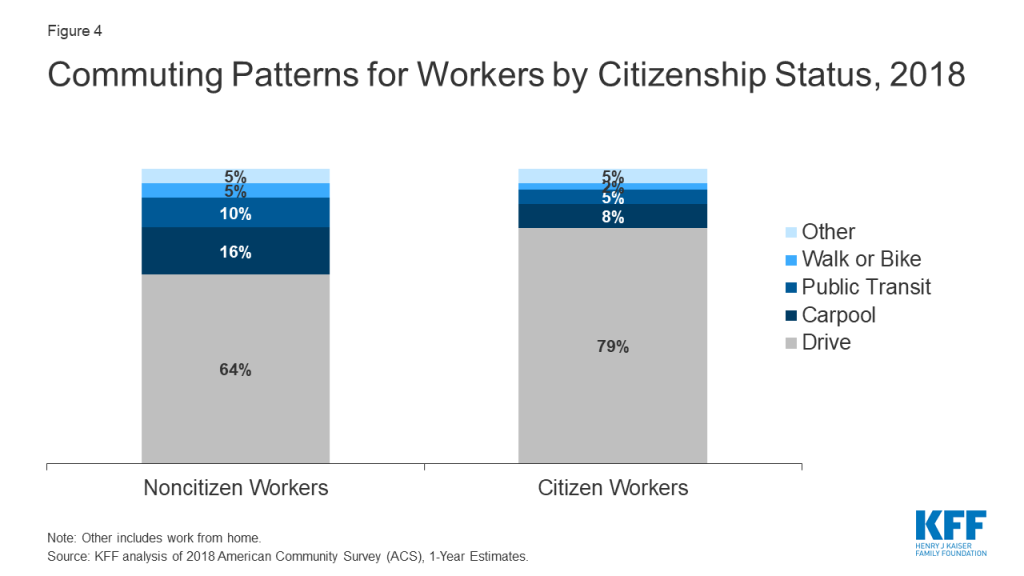

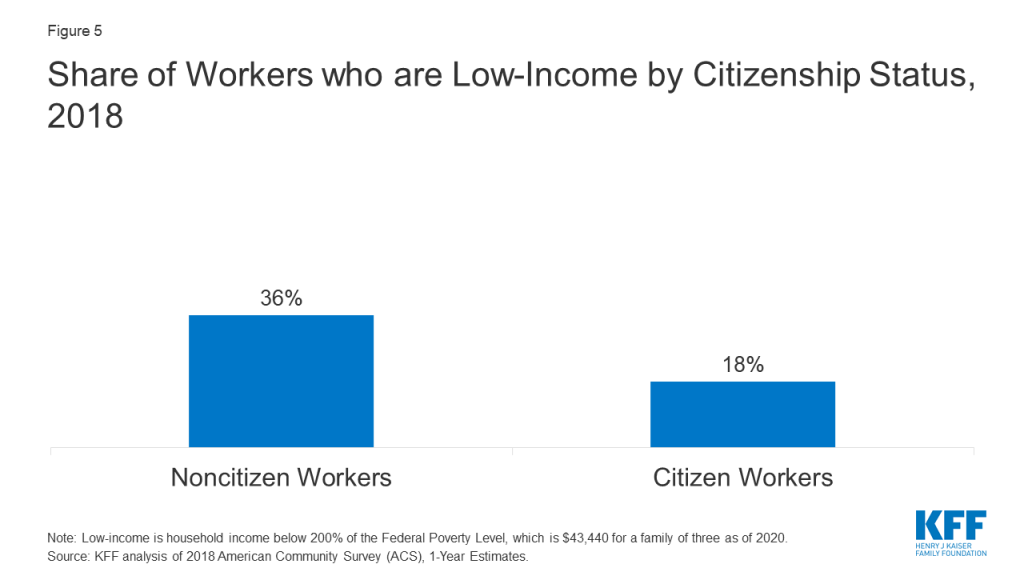

- Noncitizen workers are more likely to rely on public transportation to commute to their job and to be low-income compared to their citizen counterparts. Nearly one in four (24%) noncitizen workers rely on public transportation or carpools to commute to their job compared to 12% of citizen workers. They also are twice as likely live in a low-income household compared to citizen workers (36% vs. 18%).

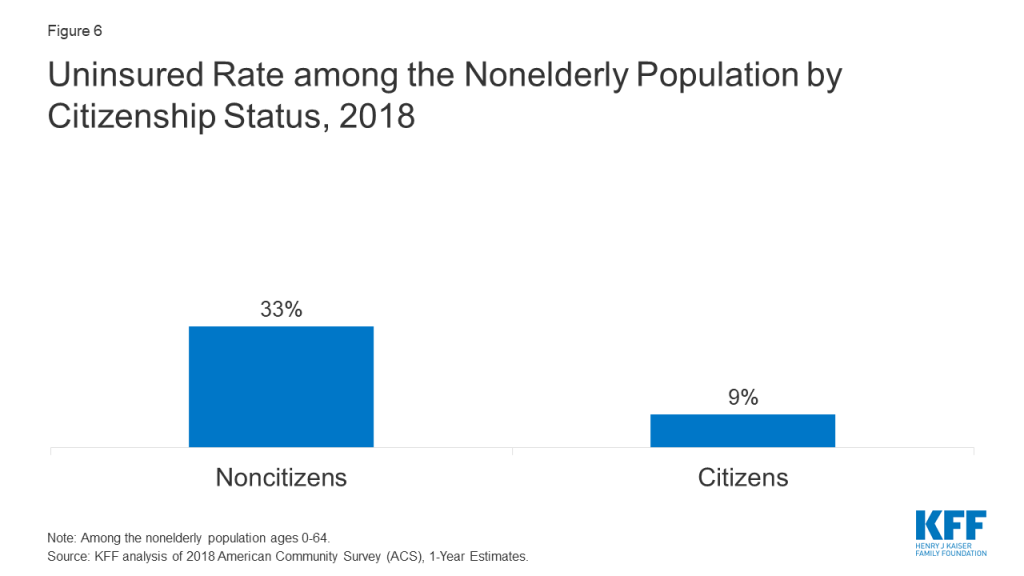

- Noncitizen immigrants are significantly more likely to be uninsured than citizens. Among the nonelderly population, 33% of noncitizen immigrants are uninsured compared to 9% of citizens.

Taken together, noncitizen immigrants’ living, working, and commuting situations increase their risk for exposure to coronavirus. They are more likely to live in larger households in densely populated areas that make social distancing challenging. Moreover, because many noncitizens workers are employed in jobs that cannot be done from home and have lower incomes, many cannot afford to stay home to limit risk of exposure and/or if they are sick. Their lower incomes and work in service industries that have experienced cutbacks amid the pandemic also increase their risks of experiencing financial hardship. Noncitizen immigrants also may have difficulty accessing testing and treatment due to their higher uninsured rate and immigration-related fears. Although noncitizen immigrants face increased risks associated with the pandemic, restrictions limit immigrants’ eligibility for federal health and financial relief provided in response to COVID-19. Further, those who are eligible for assistance may be reluctant to access services or supports due to immigration-related fears. The extent to which COVID-19 response efforts address challenges facing immigrant families has implications for immigrant families as well as the health and economic stability of the broader population, particularly given the role immigrants play in the nation’s workforce.

Issue Brief

Overview of Noncitizen Immigrants

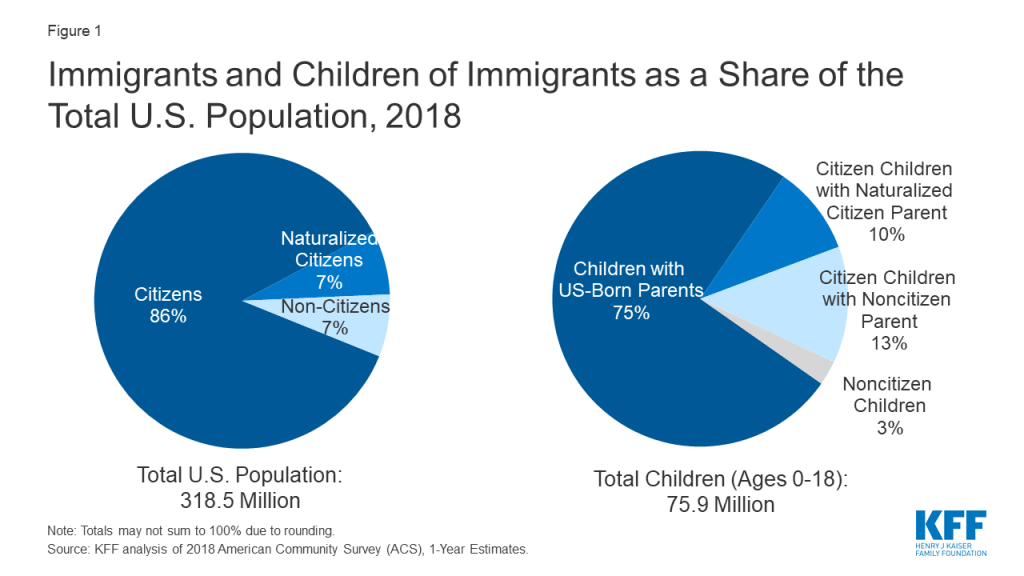

As of 2018, there were nearly 22 million noncitizen immigrants living in the United States, making up roughly 7% of the total population (Figure 1). Noncitizens include lawfully present and undocumented immigrants. Many individuals live in mixed status families that may include lawfully present immigrants, undocumented immigrants, and/or citizens. Over two-thirds (67%) of noncitizens lived in a household (which may include their family or unrelated household members) with a citizen. While there are few noncitizen children overall, about 10 million or nearly 13% of citizen children have a noncitizen parent.

Key Characteristics of Noncitizen Immigrants

This analysis presents data on the living situations, employment and commuting patterns, income, and health insurance for noncitizen immigrants prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is based on KFF analysis of 2018 American Community Survey data (see Methods for more details.) Although these data show characteristics of noncitizen immigrants prior to the pandemic, they provide insight into the health and financial risks they face associated with the pandemic.

Living Situations

Non-citizen immigrants are more likely than citizens to live in larger households and urban areas, potentially increasing their risk of exposure to the virus. Overall, 33% of noncitizen immigrants live in a household with more than four people compared to 21% of citizens, and 8% nonelderly noncitizen immigrants live with someone aged 65 or over. Noncitizens also are more likely than citizens are to live in an urban area (96% vs. 86%).

Employment, Commuting, and Income

The nearly 13 million noncitizen workers, who make up 8% of the overall workforce, are concentrated in jobs that generally cannot be done virtually. Nearly one in four (23%) noncitizen workers are in the construction and restaurant and food services industries (Figure 2).

Occupations that employ the largest numbers of noncitizen workers include construction laborers, cooks, janitors and building cleaners, agricultural workers, and maids and housekeepers, where they also account for a high share of all workers. For example, they account for over four in ten agricultural workers (42%), 30% of maids and housekeepers, one in five (20%) cooks, and 16% of janitors and building cleaners (Figure 3). Noncitizen workers also contribute to the health care workforce. They make up 5% of workers in the health care industry and up to 10% of all aides and personal care workers and direct contact support workers in home health care and nursing and residential care facilities.

Prior to the pandemic, noncitizen workers were more likely than citizen workers to rely on public transportation or carpools to commute to their job (Figure 4). Noncitizens were less likely to drive alone to work compared to citizen workers (64% vs 79%) and were twice as likely as their citizen counterparts were to carpool (16% vs. 8%) and use public transit (10% vs. 5%).

Noncitizen workers twice as likely to be low-income (household income below 200% of the federal poverty level or $43,400 for a family of three as of 2020) compared to their citizen counterparts (36% vs. 18%) (Figure 5).

Health Insurance

Noncitizen immigrants are significantly more likely than citizens to be uninsured. Among the nonelderly population, 33% of noncitizen immigrants are uninsured compared to 9% of citizens (Figure 6).

Implications

Taken together, noncitizen immigrants’ living, working, and commuting situations make them more likely to be at risk for exposure to coronavirus. They are more likely to live in larger households in densely populated areas that make social distancing challenging. Moreover, because many noncitizens workers are employed in jobs that cannot be done from home and have lower incomes, many may put themselves at risk of exposure to coronavirus because they cannot afford to stay home and miss work. Noncitizen workers may also face increased risk of exposure due to their reliance on public transportation and carpools. Although data on infections and deaths among immigrants are limited, there have been outbreaks among workers in meatpacking plants and farmworkers, which include high shares of immigrant workers. Moreover, reports indicate that outbreaks are spiking along the U.S.-Mexico border, where large numbers of immigrants live.

Noncitizen immigrants also face increased risks of financial difficulties due to economic impacts of the pandemic. Noncitizen workers are at risk for job cutbacks because many are working in service industries, such as restaurants and food services. Other analysis finds that initial job losses amid the pandemic have been particularly high among immigrants. Given their low incomes, job loss could lead to significant financial pressures for them and their families, including increased difficulty paying for basic needs. Analysis has found that Hispanic adults in families with noncitizens are experiencing higher rates of negative employment impacts because of the pandemic than families where all members are citizens, and that they were more likely to report experiencing hardships such as food insecurity or not being able to pay their full rent or mortgage on time.

Noncitizens immigrants may face increased barriers to accessing testing or treatment due to higher uninsured rates. Immigrants are on average younger and healthier compared to citizens, meaning they face relatively lower risk of experiencing serious illness if infected with coronavirus. However, because they face increased barriers accessing health care, they may have greater challenges accessing testing and treatment that could lead them to delay or forgo seeking care. Research shows that uninsured individuals are less likely to have a usual source of care and more likely to delay or go without care compared to those with insurance. The number of uninsured individuals, including immigrants, is expected to increase as people lose jobs and job-based health coverage due to the pandemic.

Although noncitizen immigrants face increased risks associated with the pandemic, restrictions limit immigrants’ eligibility for federal health and financial relief provided in response to COVID-19.

- Health coverage and testing and treatment. Under existing rules, eligibility for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) is generally limited to lawfully present immigrants who have had lawful status for at least five years, meaning that many recent lawfully present immigrants are ineligible to enroll. Lawfully present immigrants are eligible for Marketplace coverage regardless of their length of time in the country. Undocumented immigrants are not eligible to enroll in Medicaid or CHIP or to purchase coverage through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplaces. The Families First Act as amended by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) provides a new optional Medicaid category that states can adopt to provide free coronavirus testing to uninsured individuals. However, it does not change the existing immigrant eligibility restrictions for Medicaid, and, as such, does not extend to recent lawfully present and undocumented immigrants. A portion of the $100 billion in federal funding directed to providers under the CARES Act will go to hospitals for treating uninsured patients regardless of immigration status, but how this may affect immigrant access will depend on how the funding is allocated.

- Financial assistance. The CARES Act provides financial assistance to individuals through a recovery rebate, but it is limited to people filing taxes with Social Security Numbers. Both an individual filer and his or her spouse must have a valid Social Security Number if filing jointly. Other analysis estimates that this requirement excludes 15.4 million people from receiving the rebate. Immigrants generally may qualify for regular unemployment insurance if they are work-authorized at the time they file for unemployment insurance and remain authorized during the period they receive unemployment. However, that leaves undocumented immigrants without access to unemployment support even if they were employed.

- Some states and localities have taken steps to fill in the gaps in assistance available to immigrant families. For example, as of August 12, 2020, 13 states have expanded Emergency Medicaid to cover COVID-related testing or treatment. Emergency Medicaid provides payments to states for emergency services made on behalf of individuals who are otherwise eligible for Medicaid but for their immigration status. In addition, some states and localities have established financial relief funds to assist immigrants who do not qualify for federal resources.

Growing fear and uncertainty among individuals in immigrant families may also lead to some individuals avoiding accessing services or assistance even if they are eligible for them. Immigration policy changes and enhanced immigration enforcement efforts over the past several years have led to growing fear and uncertainty among immigrant families that are leading some to avoid seeking services, including health care, and/or enrolling in public programs, including health coverage through Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). These include recent changes to public charge policy that would prevent individuals from obtaining a green card or entry into the U.S. if they are determined likely to use certain public programs, including Medicaid. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) posted an alert clarifying that it will not consider testing, treatment, or preventive care (including vaccines if a vaccine becomes available) related to COVID-19 as part of public charge determinations. In addition, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has reiterated that, consistent with its existing sensitive locations policy, it will not carry out enforcement operations at or near health care facilities, except in the most extraordinary circumstances. However, families may still be fearful of accessing services or assistance if they are uncertain about current policies.

In sum, noncitizen immigrants face an array of risks and challenges associated with the pandemic. However, they have more limited access to federal support and assistance. The extent to which COVID-19 response efforts address challenges facing immigrant families has implications for immigrant families as well as the health and economic stability of the broader population, particularly given the role immigrants play in the nation’s workforce.

Methods

This analysis is based on a KFF analysis of the 2018 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-year file. The ACS includes a 1% sample of the US population, the subset used here includes over 160,000 non-citizen observations. Industry and Occupation definitions are defined within ACS using the 2018 SOC and the 2017 NAICS – for more information see here. We define workers as adults (18+) who earned at least $1,000 during the year. Metro and non-metro areas are defined by the USDA Economic Research Service.

The ACS asks respondents about their health insurance coverage at the time of the survey. Respondents may report having more than one type of coverage; however, individuals are sorted into only one category of insurance coverage.