Trends in Workplace Wellness Programs and Evolving Federal Standards

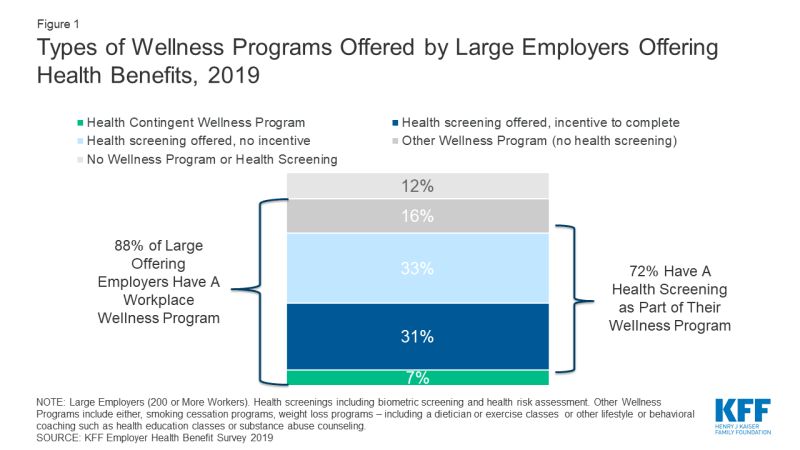

In 2019, 84% of large employers (200 or more workers) offering health benefits offered a workplace wellness program, such as those to help people lose weight, stop smoking, or provide lifestyle and behavioral coaching; in addition 4% of large offering firms have programs that exclusively do health screening, meaning in total almost 9 in 10 firms have some sort of workplace wellness program (88%). An estimated 63 million covered employees, including 59 million at large employers work for firms which offer health benefits and one of these workplace wellness programs.1 The Employer Health Benefit Survey (EHBS) has tracked the growth in workplace wellness programs from 2008 when about 70% of large employers (with 41 million covered employees) offered them. Overtime EHBS has changed the way it asks employers about their wellness and health screening offerings, for a detailed explanation see the Appendix.

Increasingly workplace wellness programs ask workers to disclose health information

Most large employers ask employees to disclose extensive personal health information via a questionnaire, known as a health risk assessment (HRA), or through biometric screening (such as a physical examination or lab test), or both. In 2019, 72% of large firms that offer health benefits, employing 48 million covered employees, offered the opportunity to complete either an HRA, biometric screening, or both. (Figure 1)

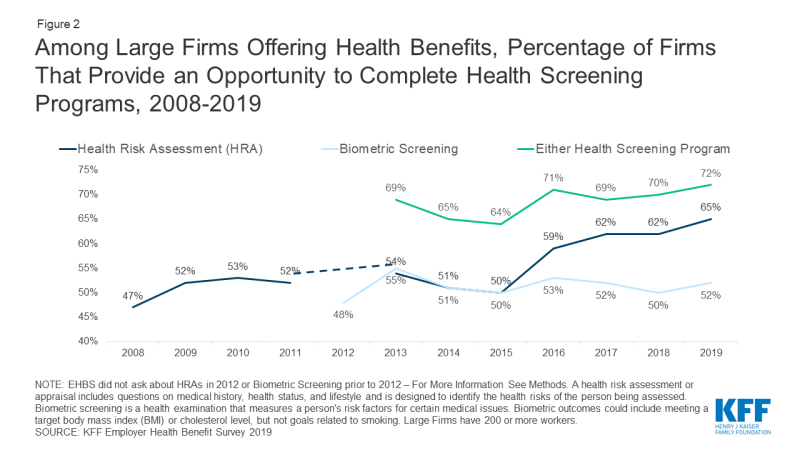

Use of HRAs has increased among large employers offering health benefits – from 47% in 2008 to 65% in 2019. (Figure 2) In 2012, the first year the EHBS asked about biometric screening 48% of large firms offered a biometric screening program similar to 52% in 2019. In addition, large employers and their health plans collect information through wearable technologies (18% in 2019). In total, 42 million covered employees worked at a large employer who had one of these screening programs that involves disclosure of personal health information.

Figure 2: Among Large Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Firms That Provide an Opportunity to Complete Health Screening Programs, 2008-2019

Financial incentives to complete health screenings

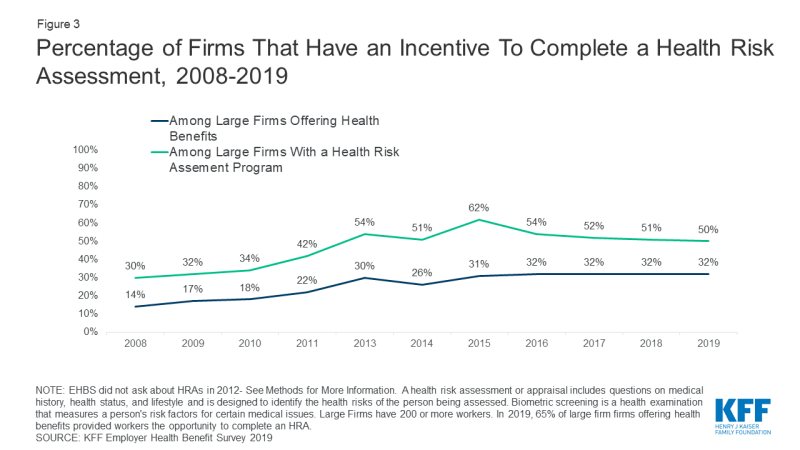

Employers that offer health risk assessments in their wellness programs increasingly use financial incentives to encourage workers to disclose health information. (Figure 3) In 2019, almost a third (32%) of large firms offering health benefits offered incentives to complete a HRA, compared to 14% in 2008.

Figure 3: Percentage of Firms That Have an Incentive To Complete a Health Risk Assessment, 2008-2019

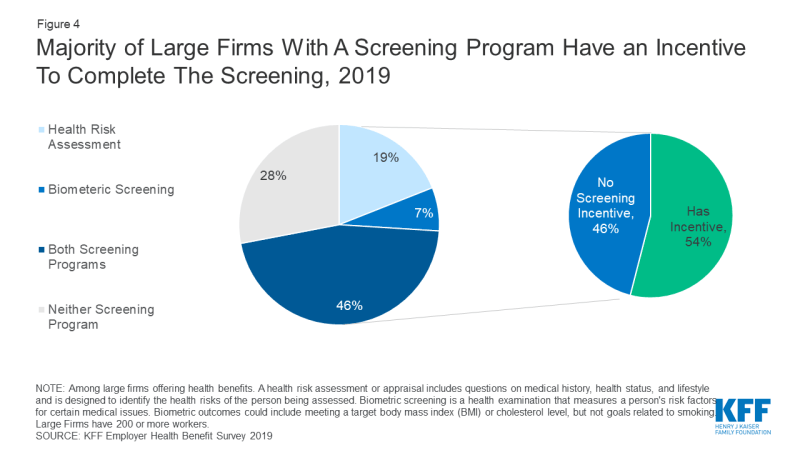

A small percent of large offering employers (7%) offer incentives to not only disclose health information but also to achieve biometric outcomes such as a target BMI or cholesterol level. These so-called health contingent wellness programs were authorized by federal regulation in 2006, and later by the Affordable Care Act (see timeline). The share of large employers offering so-called health contingent wellness programs has remained about the same since 2012.

Overall, among large employer wellness programs with health screening, including health-contingent programs, a majority (54%) apply financial incentives for participants to complete the health screening and disclose health information. (Figure 4) Nearly 28 million covered workers are in these firms. In some cases, these incentives or penalties may also apply to workers not enrolled in the health plan (34%) or an enrolled worker’s spouse (49%).

Figure 4: Majority of Large Firms With A Screening Program Have an Incentive To Complete The Screening, 2019

Size and effectiveness of financial incentives

In 2019, 20% of large firms with a wellness or health screening incentive had a maximum incentive of more than a $1,000. On average, the maximum value of the incentive was $783. Firms may provide incentives in a variety formats, including discounts or surcharges to the employee’s health premium contribution, cash, or merchandise. Incentives may reward or penalize workers for combination of activities.

We can get a sense of the size of these incentives/penalties by comparing the average premium contribution for single coverage to the average maximum reward. At firms with a wellness program incentive, covered workers’ pay $1,357 per year for single coverage premiums, not quite twice as much the maximum average penalty or incentive of $783. There is tremendous variation in employer incentives, but at some firms wellness penalties can be a significant cost for covered workers.

Participation in wellness screening programs is not high, even with incentives. A previous analysis of the 2016 Employer Health Benefit Survey, found that at large firms with an incentive for completing a health risk assessment, 50% of workers complete the assessment compared to 31% at firms with no incentive. Most large employers (61%) say either that financial incentives are either “not at all effective” or only “somewhat effective” in encouraging employee participation in wellness programs, or they don’t know if incentives are effective.

Workers may opt not to participate in wellness programs to protect the privacy of their health information, because they don’t find the program convenient, and/or for other reasons. To the extent wellness program incentives trigger financial penalties for non-participation, workers may find them burdensome, as a recent legal challenge demonstrates.

Yale University Health Expectation Program (HEP)

In 2017, Yale University implemented a new employee wellness program for its unionized clerical, technical, food service, and maintenance staff and their spouses. Employees and spouses covered by Yale medical plans are automatically enrolled in HEP, and then must follow screening recommendations. Those diagnosed with or having risk factors for certain conditions (such as diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia) can also be required to participate in a health coaching program. Trestle Tree is the wellness vendor that administers the health coaching program in partnership with a second vendor, HealthMine, which receives all health data on workers covered by the program. In addition to data collected through screening, health insurance claims data, including pharmacy claims, for all health plan enrollees is regularly transferred to HealthMine, regardless of whether enrollees participate in HEP.

Members may opt out of participating in HEP if they pay a weekly fee of $25, or $1,300 for the entire year, which is deducted from their paycheck. The average annual salary for a Yale food service worker is reportedly less than $37,000. HEP participants who don’t comply with the program are also subject to the $25 weekly fee. In one reported case, a campus cook and breast cancer survivor who had undergone bilateral mastectomy was nonetheless told she would be fined $25/week unless she had a mammogram.

In 2019, this employee and several others brought a class action suit against Yale University, arguing that it coerces employees and their spouses to turn over health information in violation of the ADA and GINA, federal laws that permit collection of personal health information by employers only through voluntary wellness programs.

In response, Yale points out this wellness program was agreed to by the union as part of its collectively bargained health benefits package. Under the agreement, the HEP took effect in 2017, when EEOC regulations permitting wellness financial incentives were still in effect. Yale also argues the wellness program financial incentive is modest and does not render the choice to participate as involuntary.

Federal rules applicable to wellness program incentives

Questions about the permissibility of these workplace wellness incentives under federal law are ongoing. Two federal employment nondiscrimination laws – the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA) – prohibit employers from making inquiries about employee health information or genetic information with limited exceptions, including through voluntary workplace wellness programs. Initially, regulations and enforcement guidance defined “voluntary” wellness programs to be those that neither require participation nor penalize employees for nonparticipation. In 2016, new federal regulations issued by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) re-defined voluntary wellness programs to include those that impose financial incentives up to 30% of the cost of self-only coverage (or more than $2,100, based on the average cost of self-only group health plan coverage in 2019). The agency asserted that it did so to permit wellness program incentives consistent with those permitted under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) [see box], but that nonetheless “prevent economic coercion that could render provision of medical information involuntary.” However, a federal district court found that EEOC did not provide sufficient justification for its wellness program incentives limits, and ruled this change in the definition of “voluntariness” to be arbitrary and capricious. EEOC repealed the financial incentive provisions of its ADA and GINA wellness rules in December 2018. The Agency’s regulatory agenda indicates further rulemaking on wellness is planned.

Meanwhile, other provisions of the ADA and GINA wellness rules remain in effect for all workplace wellness programs that make disability-related inquiries or conduct medical examinations. Such programs must be “reasonably designed.” Among other requirements, reasonably designed programs must provide employees with advanced notice clearly explaining what medical information will be obtained, how the medical information will be used, who will receive the medical information, the restrictions on its disclosure, and methods the employer/wellness program uses to prevent improper disclosure of medical information. In addition, programs must be reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease.

HIPAA, ACA, and Workplace Wellness Incentives

Since enactment of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), group health plans have been prohibited from discriminating (varying eligibility or premium contribution) based on health status. HIPAA permitted an exception to the nondiscrimination requirement: group health plans can vary premiums or cost sharing through workplace wellness programs. Regulations in 2006 permitted employers to offer so-called health-contingent wellness programs that vary premium contributions on the ability of employees to meet biometric targets, such as normal weight or blood sugar, as long as wellness programs meet other standards, including limits on the amount of financial incentives. The regulation did not limit other incentives to participate that were not tied to meeting health outcomes.

In 2010, the Affordable Care Act codified the 2006 regulations and specified that incentives under health-contingent workplace wellness programs could be as much as 30% of the cost of the group health plan (employer plus employee share). Final regulations implementing the 2010 workplace wellness provisions were published in 2013. Again, regulations did not limit other wellness program incentives to participate that were not tied to meeting heath outcomes, but did specify that compliance with ACA wellness program requirements does not mean the program complies with other federal employment nondiscrimination laws, including the ADA and GINA.

Since these statutory and regulatory changes permitting health-contingent wellness program incentives, few employers have adopted this type of wellness program. In 2019, 7% of large employers offered health contingent wellness programs.

Health information collected through reasonably designed wellness programs can be used to provide meaningful feedback or advice to employees about their health or risk status; health information collected through wellness programs can also be used, in aggregated form, to design effective disease management programs or treatments. However, the EEOC regulations specify that a wellness program is not reasonably designed if it exists mainly to shift costs from the employer to targeted employees based on their health, or to simply give an employer information to estimate future health care costs.

Among large firms with a screening program in 2018, 62% report using information from their screening programs to target health promotion programs or communications, 53% use information to design new programs, 43% use information to measure health plan costs, 67% use information to understand employee health risks, and 24% use information as the basis for an incentive program

Discussion

Despite the prevalence of workplace wellness programs, numerous studies find limited evidence of their effectiveness in promoting health or preventing disease. There are considerable challenges with measuring the impacts of workplace wellness program. First, healthier individuals are more likely to participate in wellness programs, making it hard to determine if differences in health outcomes reflect program effectiveness or the people who elect to participate. Secondly, workplace programs come in many shapes and sizes, with many programs focusing more on health screening than health promotion programs.

Recently two randomized controlled trials found limited improvements in health outcomes from employer wellness programs. The first trial, conducted at the University of Illinois, found that implementing a $200 incentive increased participation in the health screening from 46.9% to 62.5% of employees. Employees completing screening were able to participate in health coaching, disease management and wellness classes. After a year, the program did not find any impacts on medical spending, absenteeism, and health outcomes between participants and the control group. Individuals who participated in the program were more likely to complete a health screening and say that management cared about their health and wellbeing. One consequence of the programs was that lower wage workers were more likely to be penalized, exacerbating concerns about affordability.

A second trial, involving 20 worksites for a large US warehouse retail company did not find improvements in health outcomes, spending, or utilization over an 18-month period. The intervention did find an 8% percentage point increase in the share of employees who regularly exercised and their self-reported health status. Workers were eligible for up to $250 dollars in rewards if they participated in a wellness vendor’s programs, including nutrition and exercise classes.

Federal law permits collection of health information from workers through voluntary workplace wellness programs, and the EEOC has given notice it will revisit the issue of incentives in future rulemaking. How federal standards for wellness incentives evolve remains to be seen. Even as standards evolve, though, most large employer wellness programs continue to collect personal health information, and most of these screening programs incentivize workers to provide it. When incentives are applied to the premium contribution for group health benefits, failure to participate in wellness programs can substantially increase the cost workers would otherwise pay for their health coverage.

Methods

The KFF Employer Health Benefits Survey is an annual, nationally representative sample of non-federal public and private employers with three or more employees. The survey asks extensive questions about the firm characteristic and the benefits they offer. In 2019, 2,012 firms completed the full survey, including 1,133 firms with 200 or more employees. While less than 2% of firms have 200 or more employees, 73% of covered workers work at these firms. Therefore, the smallest firms dominate any statistics weighted by the number of employers. For this reason, most statistics are reported for just larger firms. For more information on the Employer Health Benefit Survey see here.

Every year we review and revise the questions asked in the employer health benefit survey. Questions are adapted to changes in the marketplace, to improve the clarity and ease for respondents, or to reduce the overall burden of the survey. Given the rapidly changing landscape of employer wellness and health screening programs, these questions saw several revisions over the last decade, with a major revision in 2014. Changes to question wording can have an effect on estimates. In this analysis we reported trends of comparable questions over time, the exact question wording are provided here. In some years we elected not to ask a question in order to make space for other topics. In addition, interviewers are provided notes to address common questions for respondents, the notes provided for any given question are available on request. These notes typically have minor changes every year and are infrequently read to respondents.

Health Risk Assessment

- Between 2008 and 2011: “Does your firm give its employees the option to complete a health risk appraisal or health risk assessment? A health risk assessment or appraisal includes questions on medical history, health status, and lifestyle and is designed to identify the health risks of the person being assessed.”

- 2013 and 2014: “Does your firm provide the opportunity for employees to complete a health risk appraisal or health risk assessment? A health risk assessment or appraisal includes questions on medical history, health status, and lifestyle and is designed to identify the health risks of the person being assessed.”

- Since2015: “A health risk assessment includes questions on medical history and lifestyle and is designed to identify a person’s health risks. Does your firm or insurer provide an opportunity to complete a health risk appraisal or assessment?

Biometric Screening

- Between 2013 and 2014: Which of the following wellness or health promotion programs does your firm or any of your health plans offer to at least some employees: Biometric Screening?

- Biometric screening is an in-person health examination conducted by a health professional to 2015: measure an employee’s risk factors such as cholesterol, blood pressure, and body mass index. Does your firm or insurer provide an opportunity, or ask employees, to complete biometric screening to identify health issues that the employee may have?

- Since 2016: Biometric screening is an in-person health examination conducted by a health professional to measure an employee’s risk factors such as cholesterol, blood pressure, and body mass index. Does your firm or insurer provide an opportunity for employees to complete a biometric screening?

Incentives for Health Risk Assessments

- Between 2008 and 2009: Does your firm offer financial incentives to employees that complete a health risk appraisal or health risk assessment?

- Between 2010 and 2014: Does your firm offer financial incentives to employees that complete a health risk appraisal or health risk assessment, anything from premium discounts to cash?

- Since 2015: Does your firm use incentives or penalties to encourage employees to complete a health risk assessment?

Incentives for Biometric Screening Programs

- Between 2013 and 2014: Are employees rewarded or penalized financially based on whether they meet specified biometric outcomes such as meeting a target body mass index (or BMI) or cholesterol level? Please do NOT include incentives or penalties related to smoking or tobacco use in answering this question.

- Since 2015: Does your firm use incentives or penalties that encourage employees to complete biometric screening?

Wellness and Health Promotion Programs

- Since 2015: Which of the following wellness or health promotion activities does your firm, any of your health plans, or 3rd party vendors offer to at least some employees? Please select all that apply.

- a. Programs to help employees stop smoking or using tobacco

- b. Programs to help employees lose weight, including monitored exercise programs, nutrition counseling or an on – site dietician (Note: Online programs count only if the program is interactive. Walking clubs count if they are structured.)

- c. Other lifestyle or behavioral coaching, such as health education classes, stress – management or substance abuse counseling (If needed: Including for opioids.)

- Between 2012 and 2014: Which of the following wellness or health promotion programs does your firm or any of your health plans offer to at least some employees?

- a. Weight loss program

- c. Smoking cessation program

- d. Lifestyle or behavioral coaching (other than smoking cessation)

- f. Classes in nutrition or healthy living

- Between 2008 and 2011: Which of the following wellness programs or benefits does your firm or any of your health plans offer to at least some employees?

- a. weight loss programs

- c. smoking cessation program

- d. personal health coaching

- e. classes in nutrition or healthy living

- Between 2005 and 2006: Does your firm offer any of the following wellness programs to your employees?

- a. fitness programs or on-site health club facilities

- b. smoking cessation

- d. weight loss