Changing Rules for Workplace Wellness Programs: Implications for Sensitive Health Conditions

Legislation pending in Congress, HR 1313, would substantially change federal rules governing workplace wellness programs. Today several federal laws apply to workplace wellness programs. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) sets standards for a certain type of wellness program, called health contingent programs, used by 8% of large firms (200 or more workers) that offered health benefits in 2016. Health contingent wellness programs vary health plan premiums or cost sharing based on whether a person achieves a biometric target, such as for blood pressure. The ACA limits penalties that can be applied under such programs. However, it does not address personal health information collection practices under health contingent wellness programs. Nor does it limit incentives or set standards for any other types of workplace wellness programs, except to require that programs must be offered to all similarly situated individuals.

Two other laws – the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) – govern all workplace wellness programs that ask workers and their family members to disclose health information, including genetic information. Today, the vast majority (71%) of large firms have wellness programs that collect personal health information. The ADA and GINA prohibit employment discrimination based on health status or genetic information. As part of that protection, ADA prohibits medical examinations and inquiries that are not job related, and GINA prohibits requests for genetic information, though both laws make exceptions for voluntary wellness programs. Rules under ADA and GINA limit financial incentives to provide personal health information and submit to medical examinations. GINA also generally prohibits penalties for refusing to disclose genetic information, or health information about children, and both laws set other standards for the collection and use of personal health and genetic information by wellness programs.

Under HR 1313, any wellness program in compliance with ACA requirements would be deemed compliant with ADA and GINA wellness program standards. As a result, for the vast majority of workplace wellness programs today, there would be no limit on inducements that could be used to encourage workers and their family members to provide personal health information, including genetic information; and other ADA and GINA wellness standards would no longer apply to any workplace wellness programs.

This brief reviews findings from the 2016 Kaiser Family Foundation/HRET Employer Health Benefits Survey related to wellness programs and financial incentives. It also reviews findings from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) related to the incidence of certain sensitive or potentially stigmatized health conditions among adults covered under employer-sponsored health plans.

Collection of Personal Health Information by Workplace Wellness Programs, 2016

Nearly all large firms (90%) that offer health benefits (“offering firms”) offer some type of wellness program, though the term “wellness program” encompasses a range of measures from health screening to more targeted health interventions. About half (47%) of all offering firms and 83% of large offering firms offered classes, coaching, or other activities to help employees stop smoking, lose weight, or adopt healthier lifestyles.

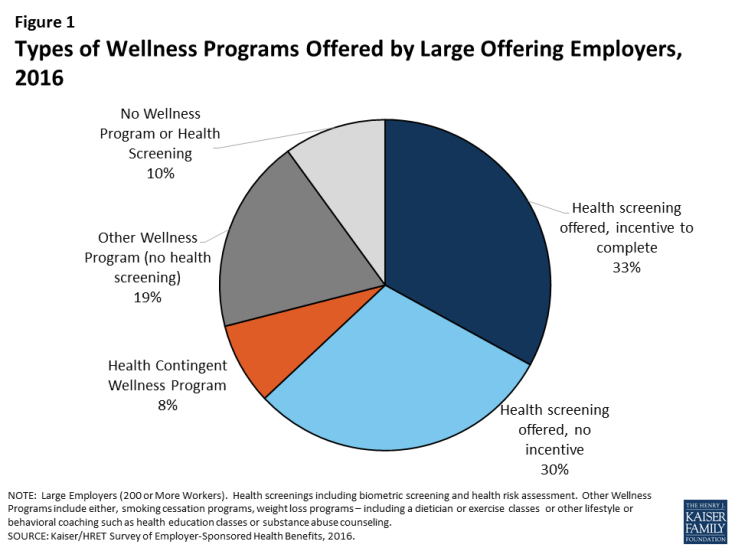

Health contingent wellness programs – Health contingent wellness programs are offered by 8% of large offering firms. (Figure 1) Such programs must meet ACA standards in order to vary participants’ health plan premiums and cost sharing based on meeting a biometric target such as for BMI or blood glucose levels.

The ACA limits financial incentives under health contingent wellness programs to no more than 30% of the total health plan premium, though the Secretary has authority to raise this cap to 50%.1 For an average cost group health plan in 2016 ($6,435 for self only coverage, $18,142 for family coverage), the average maximum incentive would be $1,930/$5,442. Among health contingent wellness programs offered by large firms in 2016, 56% set the maximum incentive at greater than $500, 27% set the maximum incentive at greater than $1,000. Other standards also apply to health contingent programs under the ACA, including requirements to offer alternative standards or accommodations to people who do not meet biometric targets. The ACA does not address information collection practices of wellness programs. (Table 1)

For wellness programs that are not health contingent programs, the only requirement under the ACA is that programs must be offered to all similarly situated individuals, regardless of health status.2

| Table 1: ACA Workplace Wellness Program Standards | |||

| Health Contingent Programs | Other Worksite Wellness Programs | ||

| Limits on Incentives |

|

|

|

| Standards for Program Design |

|

|

|

| Eligibility |

|

|

|

| Standards for information collection |

|

|

|

| Confidentiality * |

|

|

|

| * The ACA did not address confidentiality. However, HIPAA privacy rules apply to information collected by workplace wellness programs that are offered in conjunction with group health plans. Employer-sponsored health plans are covered entities, subject to HIPAA, but not the employers that sponsor the plans. | |||

Health screening wellness programs – Seven in ten large offering firms offer health screening tools to gather information about workers’ health and risk status (71% in 2016). Screening tools include health risk assessments (HRA) – questionnaires that ask workers to self-report on their health status, medical history, behaviors and attitudes – and biometric screenings – physical exams by a health professional to gather current health data, often including body mass index, blood pressure, blood cholesterol, and blood sugar levels. In 2016, 59% of large offering employers offered an HRA and 53% offered biometric screening. By definition, health contingent wellness programs include a health screening component, although 93% of large firm workplace wellness programs that offer health screening are not health contingent programs – that is, they do not also vary participants’ health plan premium or cost sharing based on the results of health screening. In 9% of large firm programs with screening, screening is the main component with no other offer of wellness activities included in the KFF/HRET survey.3

Incentives to complete wellness program health screening – In 2016, most (56%) large firms offering wellness screening tools offered incentives to complete them. Some incentives were nominal, such as gift cards or prizes. However, over half of firms with incentives for biometric screening (52%) and health risk assessment (51%), require employees that do not complete the screening pay higher premiums and/or cost sharing, compared to those that do.

Under the ADA and GINA, federal requirements apply to workplace wellness programs that collect workers’ health information and genetic information. Such information can only be collected through voluntary worksite wellness programs. Recent regulations issued by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) re-defined “voluntary” under both laws to permit financial inducements as great as 30% of the cost of self-only health coverage – on average, $1,930 in 2016, or twice that amount if spouses can also participate. Recent GINA rules also require that individuals generally cannot be penalized for refusing to submit genetic information to a wellness program and prohibit incentives to disclose health information about employees’ children. The laws also set other standards for voluntary workplace wellness programs. (Table 2)

| Table 2: ADA and GINA Standards for Workplace Wellness Programs that Request Personal Health or Genetic Information | ||

| ADA | GINA | |

| Limits on Incentives |

|

In addition:

|

| Standards for Program Design |

|

In addition:

|

| Standards for information collection |

|

|

| Confidentiality |

|

In addition:

|

Wellness programs and sensitive health conditions

Among large firms with an incentive for completing a health risk assessment, 50% of workers complete the assessment compared to 31% at firms with no incentive. Overall in 2016, 41% of workers at large firms that offer an HRA actually participated in the screening, in 2016. One commonly cited reason is concern for the privacy of personal health information. Wellness program HRAs typically include questions about health risks or conditions which people may consider sensitive, especially in a workplace context. For example, HRAs commonly ask whether and to what extent individuals feel stress, anxiety or depression, whether and how frequently individuals consume alcohol or use illicit drugs, information about current prescription drug use and other medical treatments, and, for women, whether they are pregnant or contemplate pregnancy in the coming year. Biometric screenings involve physical examinations, often including blood tests.

In general, many Americans are concerned for the privacy of their health information. Concern may increase when it comes to health conditions that could trigger social stigma (including perceived blame for having the condition) and discrimination. The medical literature identifies a number of stigmatized conditions, including mental health disorders, alcohol and substance use disorders, HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases, and diabetes.5 People with stigmatized conditions may sometimes take drastic measures to guard their privacy. For example, according to the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA), 8 percent of adults who perceived that they needed mental health treatment and did not receive treatment said they did not seek care because of concerns about confidentiality.6

The 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) collects data on the incidence of a range of health conditions and on the health insurance status and sources of coverage of individuals. We analyzed NSDUH data on seven potentially stigmatized health conditions to learn the number of adults with job-based health coverage who were affected. Almost three in ten of such adults in 2015, or nearly 39 million, reported having one or more of these health conditions. (Table 3) It is not possible to know from NSDUH data how many of these adults were covered through employers that also offer wellness programs.

| Table 3: Incidence of Stigmatized Health Conditions Among Adult with Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance (ESI), 2015 | ||

| Condition | Percent Adults with ESI | Number of Adults with ESI |

| Sexually Transmitted Disease (past year) | 1.9% | 2,515,067 |

| Diabetes | 9.0% | 11,671,723 |

| Mental health disorder | 15.5% | 20,213,894 |

| HIV/AIDS | 0.1% | 148,278 |

| Hepatitis B or C | 1.0% | 1,236,408 |

| Pregnant | 0.8% | 1,052,807 |

| Alcohol or substance use disorder (past year) | 7.5% | 9,690,737 |

| Any of these conditions | 29.8% | 38,819,350 |

| SOURCE: KFF Analysis of 2015 NSDUH Survey NOTE: For adults, NSDUH defines mental illness as “having any mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder in the past year that met DSM-IV criteria (excluding developmental disorders and SUDs)” |

||

Discussion

While many individuals may have privacy and discrimination concerns about their employers collecting biometric and health information, those with a stigmatized health conditions may have even stronger concerns. Even in the face of financial penalties, including higher health insurance premiums, most people offered the opportunity to participate in workplace wellness health screening programs decline to do so. Current federal law (the ADA and GINA) limit inducements employers can use to encourage workers and their family members to disclose information to wellness programs.

Legislation pending in Congress, HR 1313, would alter the legal landscape. Under this bill, workplace wellness programs would be deemed in compliance with the ADA and GINA if they comply with the ACA – which limits incentives only for health-contingent wellness programs, and which does not address other practices governed by the ADA and GINA. Nearly 90% of workplace wellness programs that ask for personal health information are not health contingent programs. As a result, under most programs, there would be no limit on penalties that could be applied to workers, spouses, and dependent children who decline to provide sensitive personal health and genetic information, and other rules on information collection practices would no longer apply. In addition, HR 1313 specifies that the “insurance safe harbor” provision of ADA applies to workplace wellness programs, notwithstanding any other provision of law. When ADA was enacted in 1990, the safe harbor had allowed insurers and employer health plan sponsors to use information, including actuarial data, about risks posed by certain health conditions to make decisions about insurability and about the cost of insurance. This meant certain practices – such as excluding pre-existing conditions or charging people more based on health status – were not considered to violate the ADA ban on discrimination. After the Affordable Care Act prohibited such practices, EEOC rules clarified that the insurance safe harbor does not apply to workplace wellness programs, even if they are offered as part of a group health plan. HR 1313 would reverse that decision.

The potential for workplace wellness programs to improve health and save costs continues to hold great appeal for employers and policymakers, alike. The challenge is to balance this potential with protections to ensure programs do not discriminate against people with health problems or compel disclosure of health information people want to keep private. As new federal standards for wellness programs are considered, it remains to be seen how these goals will be balanced.