Policy Options to Sustain Medicare for the Future

.

Preface

Policymakers are engaged in an historic effort to stimulate economic growth and reduce the Federal budget deficit and debt. Medicare, the nation’s health insurance program for adults ages 65 and over and non-elderly people with permanent disabilities, is a key part of these discussions, principally because the program accounts for 15 percent of the Federal budget and program spending is rising as a share of the budget and the nation’s gross domestic product. President Obama, Congressional leaders in both parties, and other policymakers and stakeholders have proposed changes to Medicare as part of comprehensive approaches to deficit reduction. Important differences are reflected in the various proposals in terms of the magnitude and scope of proposed changes and how program savings would be achieved. Over the next decade, Medicare is projected to grow more slowly than private health care spending on a per capita basis, but the retirement of the Baby Boom generation and rising health care costs pose fiscal challenges for the nation. How these challenges are addressed has important implications for the Federal budget, the nation’s health care system, health care providers, taxpayers, and people with Medicare.

To inform ongoing and future policy discussions, this report presents a compendium of policy ideas that have the potential to produce Medicare savings. The report discusses a wide range of options and lays out the possible implications of these options for Medicare beneficiaries, health care providers, and others, as well as estimates of potential savings, when available. Of note, this report does not attempt—nor is it intended—to endorse or recommend a specific set of Medicare program changes or reach a specific target for savings. The report also does not include options that would be likely to require additional Federal spending, such as improving benefits or strengthening financial protections for beneficiaries with low incomes. And while it is clear that health care costs in the public and private sector are interrelated and that changes in each sector directly affect spending in the other, the report does not include options to address health care costs more broadly, including public health improvement efforts that would undoubtedly affect Medicare spending, such as reducing obesity.

There are many potential pathways and policy options that could be considered to sustain Medicare for the future. For example, one approach would leave the current program structure largely intact but make modifications to features of it, for example, by adjusting existing payment rules for providers and plans or raising beneficiary cost-sharing requirements for specific services. Another approach would attempt to leverage Medicare’s significant role in the health care marketplace to create stronger incentives to promote value over volume, for example, by accelerating the implementation of delivery system reforms, promoting models of care that improve the management of care for high-cost, high-need beneficiaries, and introducing new mechanisms to constrain excess payments and utilization. And yet another approach would change the fundamental structure of Medicare from a defined benefit program to one that instead provides an entitlement to a government contribution for the purchase of coverage. Each of these pathways could accommodate some specific savings and revenue options for Medicare that have been discussed, including raising the age of eligibility, increasing the payroll tax or raising other revenues, and capping annual program spending.

To produce this report, The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation spent several months in 2012 consulting some of the nation’s top experts in Medicare and health care policy, including individuals with a wide variety of perspectives who have served in senior positions on Capitol Hill and in the Executive Branch, academia, and the health care industry. We asked for their input on defining the problem, as well as their suggestions for options, pathways, and priorities.

These experts were very generous with their thoughts, ideas, and time, for which we are extremely thankful. A list of these experts and their affiliations at the time of the interview on page iii, with the exception of a few people who requested that they not be listed. The inclusion or exclusion of specific policy options and the related discussion in this report cannot and should not be attributed to any of these experts individually or collectively.

We also conducted an extensive review of existing literature to identify potential options to sustain Medicare for the future. The report includes many options described or endorsed by the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform (the Simpson-Bowles commission), the Bipartisan Policy Center Task Force on Deficit Reduction, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), and many others. We also worked with a team of seasoned policy experts who fleshed out these concepts and ideas for inclusion in this report to present a thorough explanation of the context, impacts, and, when available, potential savings. In particular, we would like to acknowledge Robert Berenson for making significant contributions to several parts of this report, and Leslie Aronovitz, Randall Brown, Judy Feder, Jessie Gruman, Jack Hoadley, Andy Schneider, and Shoshanna Sofaer for their contributions to specific topic areas. We also would like to acknowledge Chad Boult, Susan Bartlett Foote, Richard Frank, Joanne Lynn, Robert Mechanic, Diane Meier, Peter Neumann, Joseph Ouslander, Earl Steinberg, George Taler, and Sean Tunis for their participation in small-group discussions related to specific topics covered in this report, and Actuarial Research Corporation (ARC) for providing cost estimates and distributional analysis of several options. Technical support in the preparation of this report was provided by Health Policy Alternatives, Inc. We are indebted to Richard Sorian for bringing to this project his keen policy insight and skillful editorial assistance.

This report would not have been written were it not for a few exceptionally talented and dedicated staff of the Kaiser Family Foundation. In particular, Zachary Levinson worked tirelessly and enthusiastically on nearly every aspect of this project, and Rachel Duguay helped get the project up and running. Gretchen Jacobson was instrumental in developing several areas of the report, and Jennifer Huang lent her creative talents to the exhibits and production process. We also would like to thank Carene Clark, Anne Jankiewicz, and Evonne Young for their work on the report design and layout. Lastly, we would like to acknowledge The Atlantic Philanthropies for financial support for this project.

We hope this report provides valuable information in ongoing efforts to sustain Medicare for the future.

Sincerely,

Patricia Neuman, Sc.D

Senior Vice President

Director, Program on Medicare Policy

Director, Kaiser Project on Medicare’s Future

Kaiser Family Foundation

Juliette Cubanski, Ph.D.

Associate Director

Program on Medicare Policy

Kaiser Family Foundation

.

Experts Interviewed for this Project

Joseph Antos

American Enterprise Institute

Scott Armstrong

Group Health Cooperative

Katherine Baicker

Harvard University

Donald Berwick

Center for American Progress

Jonathan Blum

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

David Blumenthal

Partners HealthCare

Sheila Burke

Baker, Donelson, Bearman, Caldwell & Berkowitz, PC

Christine Cassel

American Board of Internal Medicine

Michael Chernew

Harvard University

David Cutler

Harvard University

Duane Davis

Geisinger Insurance Operations

Karen Davis

The Commonwealth Fund

Ezekiel Emanuel

University of Pennsylvania

Judith Feder

Georgetown University

Elliot Fisher

Dartmouth College

Patricia Gabow

Denver Health and Hospital Authority

Richard Gilfillan

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation

Sherry Glied

Columbia University

Thomas Graf

Geisinger Health System

Jonathan Gruber

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Karen Ignagni

America’s Health Insurance Plans

Mark McClellan

The Brookings Institution

Marilyn Moon

American Institutes for Research

Joseph Newhouse

Harvard University

Len Nichols

George Mason University

Robert Reischauer

The Urban Institute

John Rother

National Coalition on Health Care

John Rowe

Columbia University

Earl Steinberg

Geisinger Health System

Glenn Steele

Geisinger Health System

Simon Stevens

UnitedHealth Group

Janet Tomcavage

Geisinger Health Plan

Bruce Vladeck

Nexera, Inc.

Gail Wilensky

Project HOPE

.

Introduction

Medicare’s History of Coverage and Care for Seniors and People with Disabilities

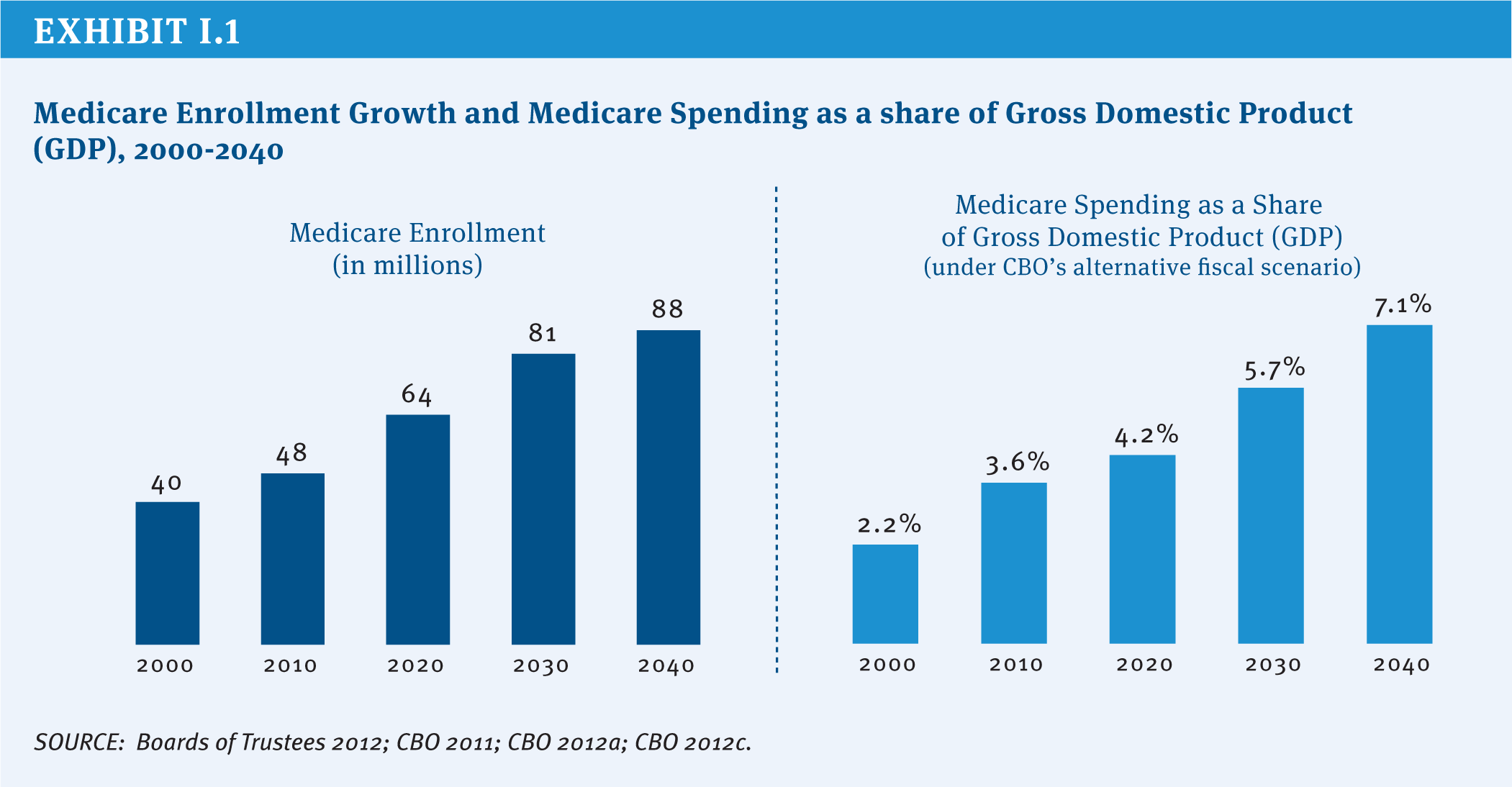

Medicare was signed into law July 30, 1965, and went into effect one year later. Since then, Medicare has provided health insurance coverage for more than 130 million Americans, including adults ages 65 and over and younger people living with permanent disabilities (HHS 2012). Medicare is a Federal entitlement program that provides a guaranteed set of benefits to all Americans who meet the basic eligibility requirements, without regard to medical history, income, or assets. In 2012, Medicare provided health insurance coverage to 50 million people. With total Medicare expenditures estimated to rise as a share of the Federal budget and the nation’s economy, Medicare is once again at the forefront of policy discussions (Exhibit I.1).

Medicare has made a significant contribution to the lives of older Americans and people with disabilities by bolstering their economic and health security and helping to lift millions of older Americans out of poverty. Prior to Medicare, more than half of all Americans over age 65 were uninsured (De Lew 2000), and nearly a third of seniors were in poverty; today virtually all seniors have Medicare coverage and the official poverty rate among those ages 65 and older is just under 9 percent (U.S. Bureau of the Census 2012). For younger people living with disabilities, Medicare has provided life-saving and life-sustaining access to care and treatment that would otherwise be out of reach for many and has allowed millions to stay in their homes rather than be institutionalized.

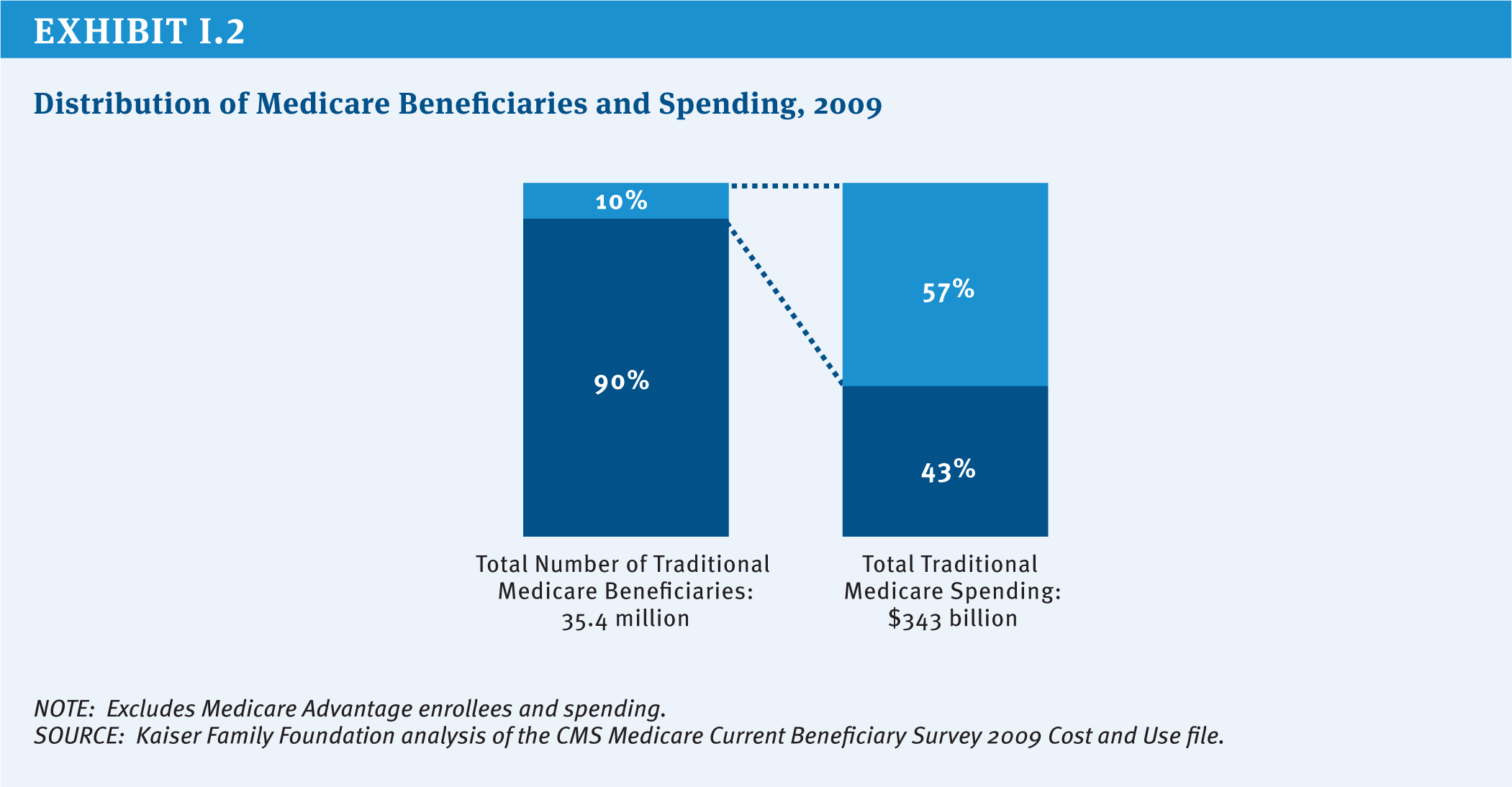

Health insurance coverage is important to people of all ages, but especially important for seniors and adults with disabilities who are significantly more likely than others to need costly medical care. Medicare pays for health care services, including, but not limited to, hospitalizations, physician services, medical devices, and prescription drugs. Each year, more than three-quarters of people with Medicare have at least one physician office visit; more than one in four go to an emergency department one or more times; nearly one in five beneficiaries are admitted to a hospital; and nearly one in 10 have at least one home health visit. In 2013, average per capita Medicare spending is projected to exceed $12,000 (Boards of Trustees 2012). While most people with Medicare use some amount of medical care in any given year, a majority of spending is concentrated among a relatively small share of beneficiaries with significant needs and medical expenses (Exhibit I.2).

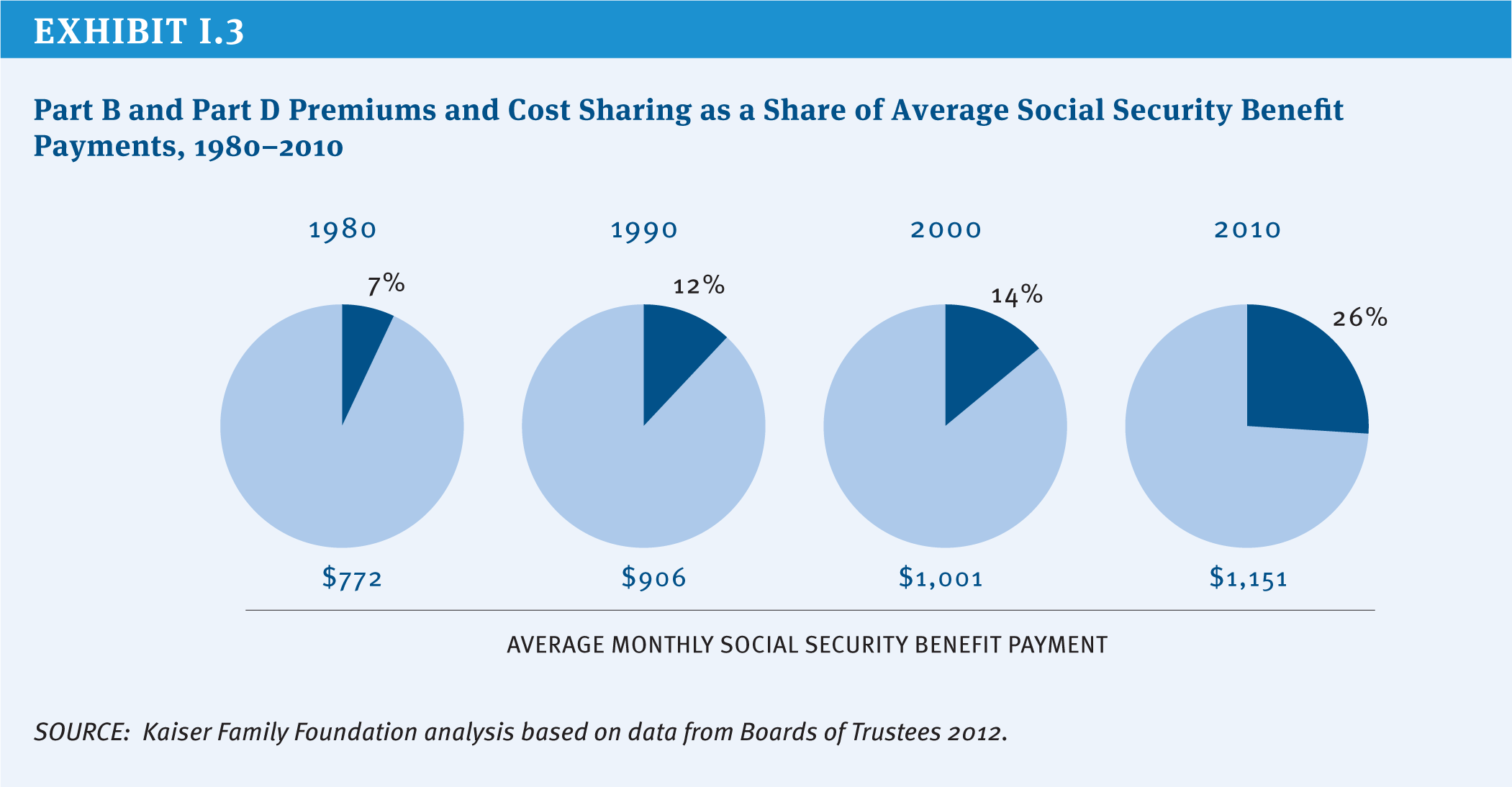

Despite the important role that Medicare plays in providing health and economic security for beneficiaries of the program, it does not cover all the costs of health care. Medicare cost sharing is relatively high and, unlike most private health insurance policies, Medicare does not place an annual limit on the costs that people with Medicare pay out of their own pockets. Many Medicare beneficiaries have supplemental coverage to help pay for these costs, but with half of beneficiaries having an annual income of $22,500 or less in 2012, out-of-pocket spending represents a considerable financial burden for many people with Medicare. Cost sharing and premiums for Part B and Part D have consumed a larger share of average Social Security benefits over time, rising from 7 percent of the average monthly benefit in 1980 to 26 percent in 2010 (Exhibit I.3). Medicare beneficiaries spend roughly 15 percent of their household budgets on health expenses, including premiums, three times the share that younger households spend on health care costs. Finally, Medicare does not cover costly services that seniors and people with disabilities are likely to need, most notably, long-term services and supports and dental services.

Medicare’s Future Challenges

Persistently high rates of growth in health care spending combined with demographic trends pose a serious challenge to the financing of Medicare in the 21st century. The number of people eligible for Medicare is projected to rise sharply from 50 million today to nearly 90 million by 2040, with a particularly high rate of growth in enrollment between now and 2030 (Exhibit I.1). According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the aging of the population is expected to account for 60 percent of the growth in Federal health spending over the next 25 years, while “excess cost growth”1 accounts for 40 percent (CBO 2012a). As such, the long-run fate of Medicare depends on solving the larger problem of rising health care costs, which pose a similar challenge to all payers, including employers, individuals, and other government programs.

The aging of the Baby Boom generation not only makes millions of Americans newly eligible for Medicare, it also reduces the number of workers paying the Medicare payroll tax, a primary source of revenue for the Medicare Part A Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund. The HI trust fund currently is projected to be solvent through 2024, but will have insufficient funds to pay full benefits beyond that point (Boards of Trustees 2012). In the past, Congress has taken steps to maintain and extend the solvency of the HI trust fund by restraining growth in Medicare spending and increasing payroll tax revenue, and will need to take action to extend the life of the trust fund at some point in the future to fully fund current benefits.

Over the course of the past five decades, Congress has made changes to Medicare on numerous occasions to address emergent issues, benefit gaps, financing challenges, spending growth, and policy priorities (See Textbox “Major Amendments to Medicare” beginning on page xi). For example, Medicare’s benefit package has been updated to include hospice benefits, outpatient prescription drugs, and more comprehensive coverage of preventive services. Medicare also has expanded the role of private entities, not only the contractors that help administer the program and process claims, but also the private health plans that provide benefits under Medicare Advantage and Part D (prescription drug coverage). Medicare payment systems have evolved over time, shifting from cost-based fee-for-service reimbursement systems to prospective and bundled payments to providers, a shift that has helped to constrain the growth in program spending.

The most recent sweeping changes to Medicare were enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010. While the ACA retained Medicare’s structure as an entitlement to a set of defined benefits, the law contains several provisions designed to reduce provider payment growth, increase revenues, improve certain benefits, reduce fraud and abuse, and invest in research and development to identify alternative provider payment mechanisms, health care delivery system reforms, and other changes intended to improve the quality of health care and reduce Medicare spending. According to CBO, these changes reduced projected Medicare spending by $716 billion over 10 years (2013–2022) (Elmendorf 2012).

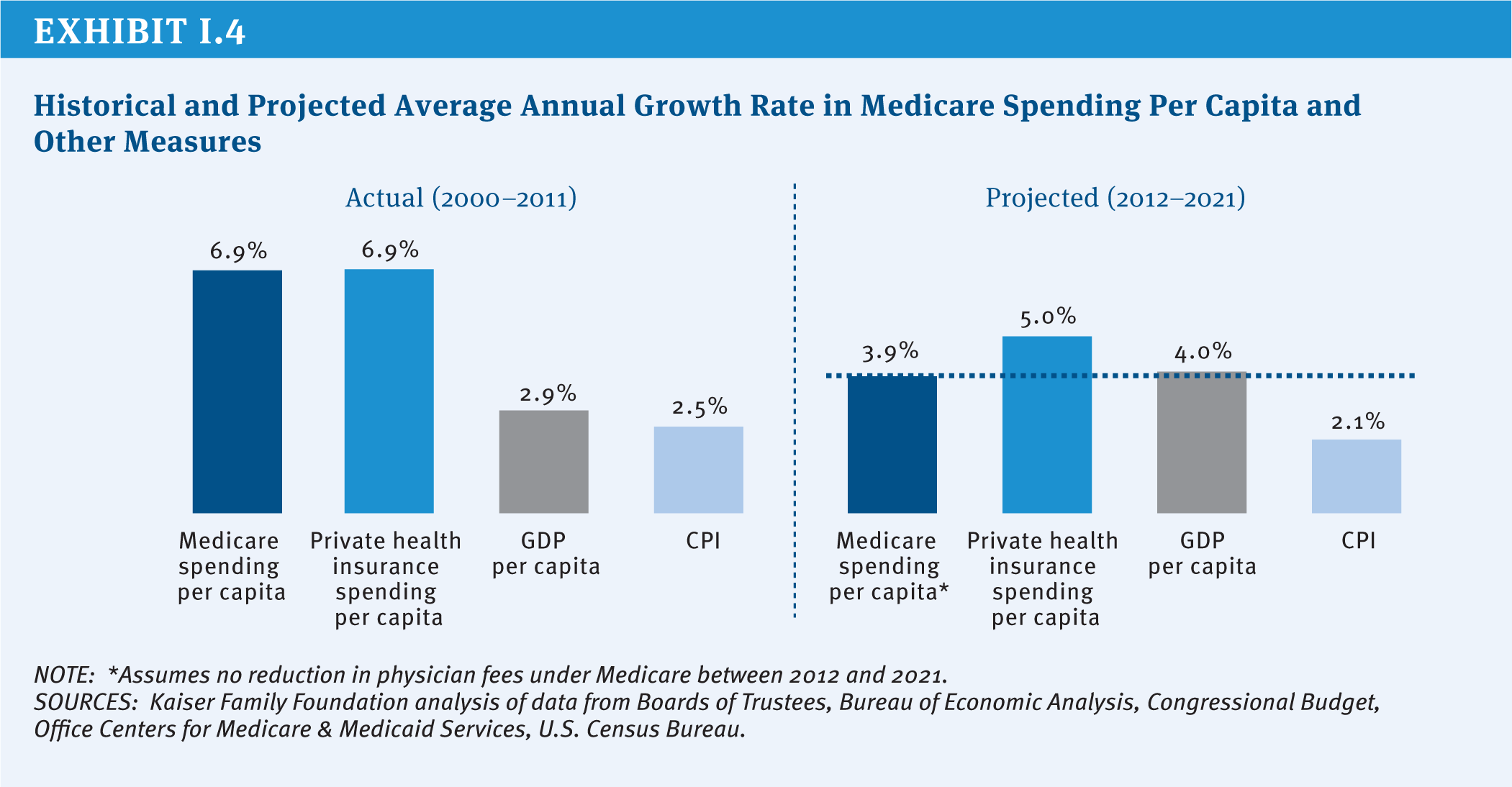

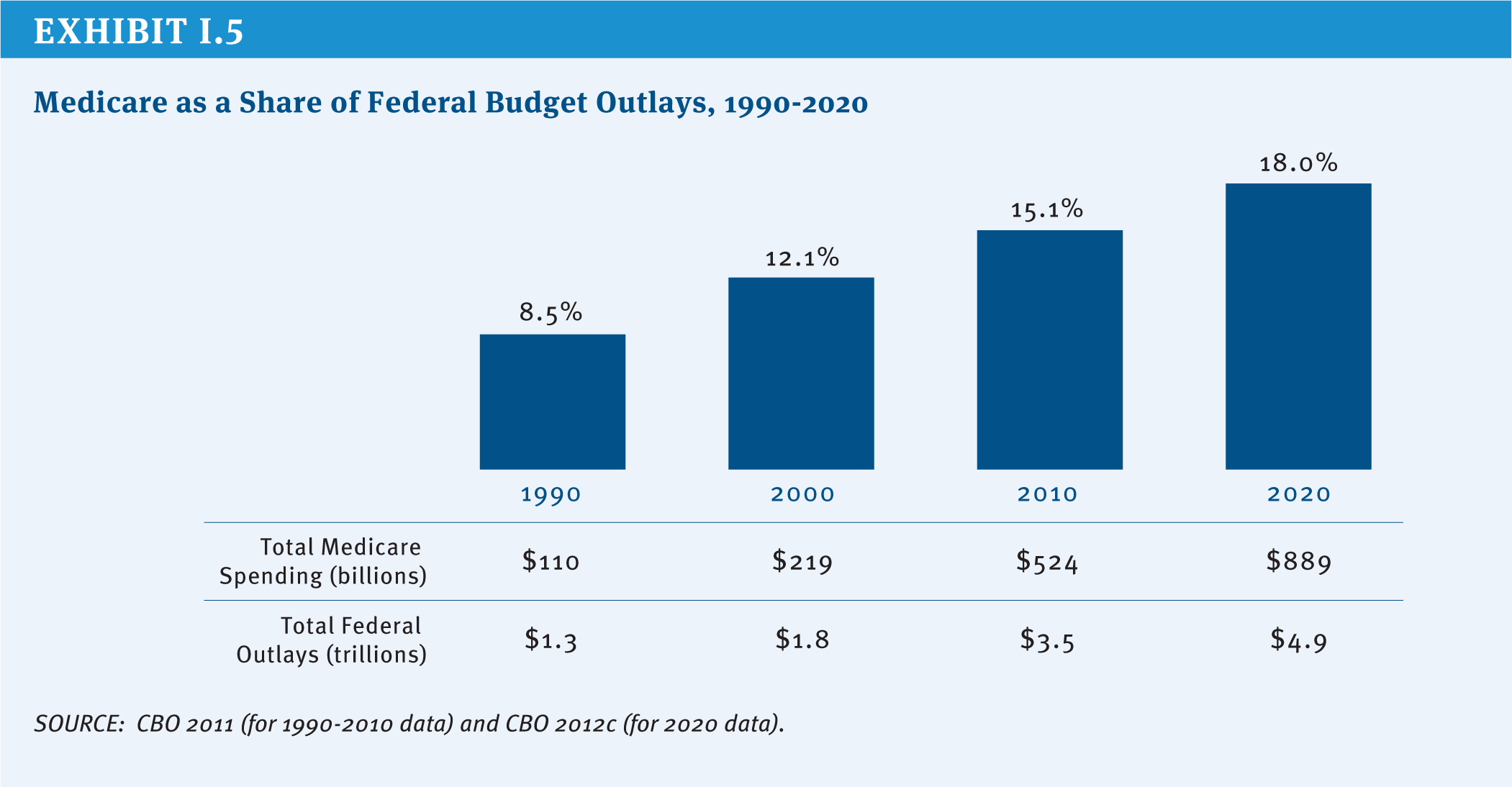

Partly as a result of payment changes enacted in the ACA, Medicare per capita spending is now projected to grow by 3.9 percent annually between 2012 and 2021, compared with 5.0 percent average annual per capita growth projected for private health insurance spending2 (Exhibit I.4). Even with the relatively low Medicare per capita growth rate projected for the next decade, policymakers face an ongoing challenge in finding ways to reduce long-term spending growth and continue to finance care for an aging population. And with Medicare spending accounting for a growing share of the Federal budget and the gross domestic product (GDP), Medicare’s challenges will be inextricably linked to ongoing deliberations over how to reduce annual Federal deficits and the national debt (Exhibit I.5).

Looking to the future, Medicare faces a number of challenges, including:

» A mismatch between projected revenues and spending that is projected to result in insufficient funds to support services that are paid for by the Hospital Insurance trust fund beginning in 2024;

» An outdated benefit design, with relatively high deductibles and cost-sharing requirements, no limit on out-of-pocket spending, and benefit gaps, that encourages beneficiaries to seek supplemental insurance and contributes to relatively high out-of-pocket spending;

» Several provider payment systems that reward volume, rather than value or patient outcomes, without adequate incentives to encourage providers to coordinate and manage patient care, particularly for high-need, high-cost beneficiaries;

» A physician payment formula, known as the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR), that aims to constrain the growth in expenditures associated with physician services, but has led to frequent Congressional intervention to avoid sudden and severe reductions in doctors’ fees; and

» An ongoing struggle to constrain the growth in health care spending, while providing fair payments to providers and plans and high-quality, affordable medical care for beneficiaries.

Given these challenges, the debate about Medicare’s future is likely to revolve around several key questions:

- How much can Medicare absorb in additional savings, and over what period of time, without negatively affecting patient care?

- How should efforts to sustain Medicare be distributed among providers, plans, beneficiaries, and taxpayers?

- What are the most promising strategies for reducing inefficiencies and promoting high-quality care: accelerated delivery system reforms; greater competition among plans and providers; value-based purchasing strategies; stronger financial incentives to encourage care management?

- Should Medicare’s basic entitlement be changed from a program that guarantees a defined set of benefits to one that provides a defined contribution for the purchase of insurance?

- Should reform efforts focus specifically on Medicare or be broadened to address the growth in health care spending across all payers?

Since the enactment of Medicare, policymakers have been challenged to balance the interests of Medicare beneficiaries, taxpayers, health care providers, health plans, and manufacturers. Today’s national economic and fiscal constraints make this task more difficult than ever. The nature of the options presented in this report underscores the scale of changes that may be in store for Medicare in the future, and the potential effects of these changes on beneficiaries and providers of care mean that debating them will be contentious. Notwithstanding the difficult choices that lie ahead in coming to consensus on Medicare program changes, the effort to sustain Medicare for the future is a vital endeavor.

Report Outline

This report presents a compendium of policy ideas that have the potential to produce Medicare savings or generate revenue, while also laying out the possible implications of these options for beneficiaries, health care providers, and others, as well as estimates of potential savings, when available. This report does not attempt—nor is it intended—to endorse or recommend a specific set of Medicare policy options or reach a specific target for savings.

The report is divided into five sections, each of which presents options within several main topic areas. Topic areas are cross-referenced where options and ideas overlap. The five sections describe options related to:

» Medicare eligibility, beneficiary costs, and program financing;

» Medicare payments to providers and plans;

» Delivery system reform and options that focus on Medicare beneficiaries with high needs;

» The basic structure of the Medicare program; and

» Medicare program administration and governance, including program integrity.

We generally rely on cost estimates from official and publicly available government sources, including CBO, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG), MedPAC, and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). For many options, no cost estimate is available from one of these sources. In a few cases, estimates from other sources are presented and noted accordingly. For a complete list of options included in this report and budget effects, see Appendix p. 197, Table of Medicare Options and Budget Effects.

References

Click to expand/collapse

Boards of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds. 2012. 2012 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds, April 23, 2012.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2011. The Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2011 to 2021, January 2011.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2012a. The 2012 Long-Term Budget Outlook, June 4, 2012.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2012b. Monthly Budget Review, Fiscal Year 2012, October 5, 2012.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2012c. An Update to The Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2012 to 2022, August 2012.

Nancy De Lew. 2000. “Medicare: 35 Years of Service,” Health Care Financing Review, 2000.

Douglas W. Elmendorf. 2012. Letter to the Honorable John Boehner, Speaker of the House, July 24, 2012.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. 2012. Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements, Historical Poverty Tables, Table 3. Poverty Status of People, by Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 1959 to 2011, 2012.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). 2012. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, unpublished estimate, 2012.

Major Amendments to Medicare

Since it was enacted in 1965, Medicare frequently has been amended in legislation to either add benefits, control costs, or both. Some of the major revisions include:

1972

Under the Social Security Amendments of 1972, Medicare eligibility is expanded to include people under age 65 with long-term disabilities (who received Social Security Disability Insurance payments for 24 months) and individuals suffering from end stage renal disease (ESRD) who require maintenance dialysis or a kidney transplant. The law also authorizes Medicare to contract with health maintenance organizations (HMOs), through either cost reimbursement or risk contracts.

1980

The Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1980 eliminates the prior hospitalization requirement for home health services, removes the 100 home health visit limitations under Part A and Part B, and requires all home health visits to be paid by Part A unless the beneficiary is only enrolled in Part B.

1982

Medicare is expanded to include a new hospice benefit under the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982. Part B premiums are set to cover 25 percent of program costs, Federal employees are required to pay the Medicare payroll tax, and HMOs are now paid based on 95 percent of the adjusted average per capita cost (AAPCC) of caring for beneficiaries under fee-for-service Medicare.

1983

As part of the Social Security Amendments of 1983, Medicare adopts a new a prospective payment system (PPS) for inpatient hospital services that pays a predetermined amount for each discharge depending on the patient’s condition. Separate rates are set for diagnosis related groups (DRGs).

1985

The Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 establishes the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), requiring hospitals in the U.S. to stabilize patients before transferring them to other facilities. COBRA also makes the Medicare hospice benefit permanent.

1987

In response to concerns raised about the quality of care in nursing homes, the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 sets new quality standards for Medicare and Medicaid certified nursing facilities while also modifying provider payments to reduce growth. Also that year, the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Reaffirmation Act of 1987 freezes Medicare payment rates in an attempt to slow Medicare spending.

1988

Congress adopts, and, in 1989, repeals key provisions of the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act that would have capped beneficiaries’ out of pocket costs and added an outpatient prescription drug benefit to Medicare financed through premiums paid by beneficiaries including means-tested payments by upper-income seniors. Provisions expanding financial protections for low-income beneficiaries in Medicare and Medicaid remain in place, however.

1989

Under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989, Medicare physician payments begin to be determined based on a resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS) based on the amount of work required to perform a service, replacing a system in which physicians were paid based on their own charges. A new “volume performance standard” is created to guard against sharp increases in the number of services provided to beneficiaries.

1990

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 sets new standards for Medigap policies, including standard benefit designs to facilitate comparisons across plans, curtails the use of preexisting condition limitations and requires new medical loss ratio requirements. Medicare benefits are expanded to include mammography screening.

1993

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 includes reductions in payments to providers as part of deficit reduction legislation. Congress also eliminates the cap on earnings subject to the Medicare payroll tax.

1997

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 makes significant changes to Medicare resulting in savings by tightening Medicare payments to providers, increasing beneficiary premiums, and other provisions. The law establishes prospective fee schedules for all part B services except hospital outpatient services and expands the types of private plans participating in a newly named Medicare+Choice program. The law replaces Medicare’s volume performance standard (VPS) with a new formula—known as the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR)—designed to guard against volume increases.

2000

The Benefits Improvement and Protection Act (BIPA) expands coverage of preventive care and increases Medicare payments to plans and certain providers. The law modifies payments to Medicare+Choice plans, increasing payments in certain rural and urban counties. It also provides Medicare coverage for people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) by waiving the 24-month waiting period.

2003

The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) adds a voluntary outpatient prescription drug program to be administered by stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) or Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug Plans (MA-PDs) financing by general revenues, beneficiary premiums, and a “clawback” of savings from the States. MMA also increases Part B premiums for higher income beneficiaries and raises payments to private health plans participating in what is now called “Medicare Advantage.”

2008

The Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008 (MIPPA) expands protection of low-income beneficiaries, adds more coverage of preventive care (including a “Welcome to Medicare” physical), and reduces the growth in payments to and imposes new restrictions and requirements on Medicare Advantage plans.

2010

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) reduces the growth in Medicare spending for Medicare Advantage plans, hospitals, and other health care providers; sets a limit on the growth in spending to be enforced through the Independent Payment Advisory Board; improves benefits by gradually closing the Part D coverage gap; expands coverage of preventive services; creates a new Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation to test and implement payment and delivery system reforms to curb costs and improve quality; increases Part B and D premiums for higher-income beneficiaries; raises the Medicare payroll tax on earnings of high-income workers; and establishes fees on manufacturers of branded prescription drugs and medical devices.

2011

The Budget Control Act of 2011 provides for reductions in Medicare spending in the event Congress cannot agree on a long-term deficit and debt reduction plan. Beginning in 2013, Medicare spending will be subject to automatic, across-the-board reductions, known as “sequestration,” that would reduce Medicare payments to plans and providers by up to 2 percent.

2013

The American Taxpayer Relief Act includes provisions to avert a reduction in Medicare physician fees for one year and extends provisions that would have expired under current law and offsets the cost by reducing payments to hospitals and Medicare Advantage plans. The law delays the sequestration of Federal payments to Medicare plans and providers for two months, repeals the Community Living Assistance Services and Supports (CLASS) program authorized under the ACA, and establishes a new Commission on Long-Term Care.