Medicaid Beneficiaries Who Need Home and Community-Based Services: Supporting Independent Living and Community Integration

MaryBeth Musumeci and Erica L. Reaves

Published:

Introduction

Introduction

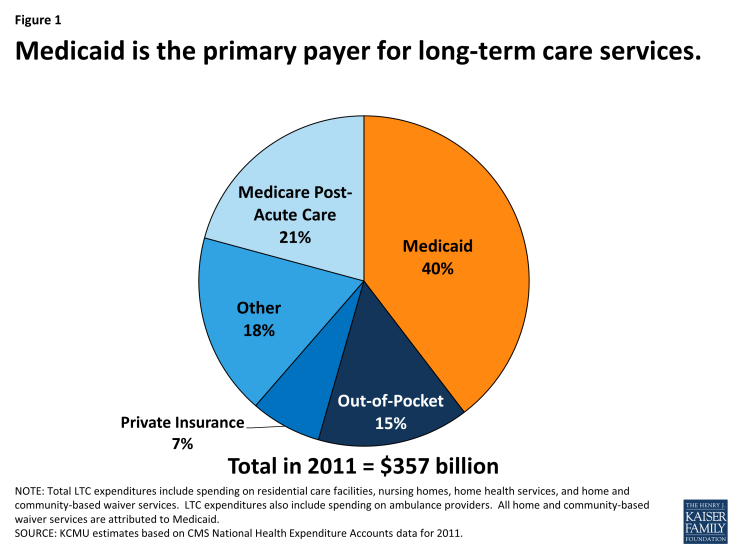

Medicaid is an important source of health insurance for seniors and people with disabilities. In addition to covering a variety of medical care, such as doctor visits, behavioral health services, and prescription drugs, Medicaid also is the primary payer for long-term services and supports (LTSS), including nursing facility care and home and community-based services (HCBS) (Figure 1).1 HCBS provide assistance with activities of daily living (such as eating, bathing, and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (such as preparing meals and housecleaning) for people with physical or cognitive functional limitations that result from age or disability. HCBS include a range of benefits, such as residential services, adult day health care programs, home health aide services, personal care services, and case management services, among others.2 HCBS may be delivered through a self-directed service model in which beneficiaries select, train, and dismiss their providers and/or control the allocation of funds among particular services in their individual budgets.3

To provide insight into the unique experiences of Medicaid beneficiaries who need HCBS, this report profiles nine seniors and people with disabilities residing in Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Tennessee.4 They include people with a range of developmental disabilities, such as autism and intellectual disabilities; physical disabilities, such as cerebral palsy and multiple sclerosis; multiple chronic health conditions; Alzheimer’s disease and aging-related dementia, and physical functional limitations associated with the aging process. Based on a series of telephone interviews conducted in 2013 by the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, these profiles illustrate how beneficiaries’ finances, employment status, relationships, well-being, independence, and ability to interact with the communities in which they live – in addition to their health care – are affected by their Medicaid coverage and the essential role of HCBS in their daily lives. We extend our appreciation to the beneficiaries and their families who so generously took the time to share their stories.

Background

Nearly 3.2 million people received Medicaid HCBS in 2010, with expenditures totaling $52.7 billion.5 Historically, the Medicaid program has had a structural bias toward institutional care because state Medicaid programs must cover nursing facility services, whereas most HCBS are provided at state option.6 While states can choose to offer HCBS as Medicaid state plan benefits, the majority of HCBS are provided through waivers.7 Unlike Medicaid state plan benefits, which must be available to all beneficiaries as medically necessary, waiver enrollment can be capped, resulting in waiting lists when the number of people seeking services exceeds the amount of available funding. In 2012, nearly 524,000 people were on HCBS wavier waiting lists nationally, with the average waiting time exceeding two years; waiting lists vary both across states and within states among waiver target populations.8

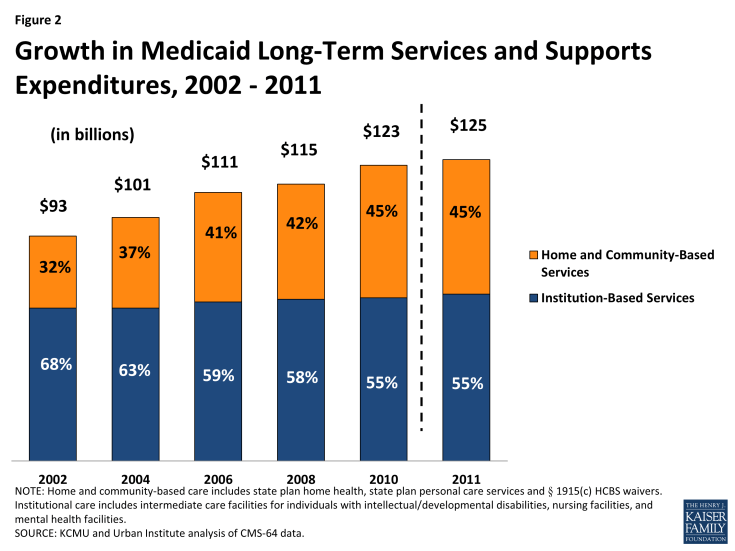

Over the last several decades, states have been working to rebalance their long-term care systems by devoting a greater proportion of spending to HCBS instead of institutional care. These efforts are driven by beneficiary preferences for HCBS, the increased population of seniors and people with disabilities who need HCBS, and the fact that HCBS typically are less expensive than comparable institutional care. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1999 Olmstead decision, finding that the unjustified institutionalization of people with disabilities violates the Americans with Disabilities Act, also has heightened the state and federal focus on community integration efforts.9 While the majority of Medicaid LTSS spending still goes toward institutional care, the proportion of Medicaid LTSS spending on HCBS continues to increase relative to spending on institutional services. In FY 2011, HCBS accounted for 45 percent of total Medicaid LTSS spending nationally, up from 32 percent in FY 2002 (Figure 2).

Key Themes

The nine Medicaid beneficiaries profiled in this report illustrate the diversity of medical conditions, personal circumstances, and needs for services and supports among seniors and people with disabilities who rely on HCBS. At the same time, their stories suggest some common themes underlying the important role of Medicaid HCBS in their lives:

- Medicaid HCBS increase independent living and community integration opportunities for seniors and people with disabilities. The beneficiaries profiled in this report uniformly express their desire to increase or maintain their independence to the maximum extent possible and emphasize the vital role of Medicaid HCBS in enabling them to do so. Mary B., a senior with dementia, was able to move from a facility to an apartment where Medicaid provides the home health aide services and medical supplies necessary to support her safely at home while her daughter is at work. Margot, a woman with cerebral palsy, and Mary A., a senior with physical functional limitations, both valued the increased independence they experienced when they were able to have their aides accompany them in the community to assist with grocery shopping and errands. Beneficiaries who have spent time waiting for services describe the transformative impact that receiving HCBS has had on their quality of life. Curtis, a young man with developmental disabilities, is now improving his independent living skills and participating in the community in an age-appropriate manner with the support of Medicaid attendant care services. Nicholas, an adult with multiple sclerosis, hopes to receive a car attachment to transport his power wheelchair as a Medicaid home and community-based waiver service, which will decrease the barriers he faces in physically accessing the community.

- Medicaid HCBS support people with disabilities who work. Several of the beneficiaries profiled in this report are working or are able and want to be employed, and Medicaid HCBS play an important role in supporting these efforts by ensuring that beneficiaries’ daily self-care and functional needs are met. Mark, a man with autism, is proud of his job as a grocery store courtesy clerk, a position that he has held for a dozen years; a group home placement would ensure that he will continue to have the necessary self-care supports that he needs to continue working as his aging parents become less able to provide for his daily needs. Margot, a woman with a master’s degree in social work, wants to be employed and could do so with sufficient home health aide hours to manage her daily physical needs as a result of functional limitations due to cerebral palsy. Aubrey, a teenager with autism, improved his social interaction and independent living skills with the help of Medicaid HCBS to the extent that he now is enrolled in college and majoring in mechanical drafting.

- Medicaid HCBS fill needs of seniors and people with disabilities that would otherwise go unmet due to beneficiaries’ limited financial resources. The profiles relate the struggles of people with low incomes trying to pay out-of-pocket for costly services while facing the competing demands of paying for housing, food, and other necessities. Patricia, a woman with multiple chronic conditions, and Mary A., a senior with physical functional limitations, both need assistance with cooking, cleaning, and grocery shopping so that they can continue to live independently in their homes. Patricia worries about her susceptibility to falling, and Mary A. needs help with bathing and dressing. At various points, both women have tried to pay out-of-pocket for services but have been unable to do so on a sustained basis on budgets limited to Social Security benefits and food stamps.

- Medicaid HCBS play a vital role in ensuring a safe stable source of care because beneficiaries’ needs often outstrip the assistance that family and friends can provide. The beneficiaries profiled in this report receive a range of informal assistance from relatives and friends, which may not be a sustainable solution for people who need long-term HCBS or those with intense care needs. Families often provide a great deal of care, and beneficiaries and their caregivers report stress in meeting on-going or deteriorating needs for services and supports. Irene’s daughter moved cross-country to provide full-time care, but as Irene’s Alzheimer’s disease progresses, her needs are becoming too great for her daughter to handle alone. Curtis and Mark are adults with developmental disabilities whose need for constant supervision and supports is likely to outlast their parents’ ability to provide that care.

- Medicaid HCBS are cost-effective as a less expensive alternative to institutional care and as preventive care to avoid more expensive deteriorations in health status. Beneficiaries emphasize their preference to live in the community instead of a nursing home not only because they feel that community living improves their quality of life and independence but also as a cost-saving measure. They also cite examples of the role of HCBS in avoiding more costly inpatient hospitalizations and emergency room visits. Nicholas, who required emergency room treatment for injuries sustained during a fall while transferring from his wheelchair to the bathroom, hopes that a Medicaid HCBS waiver will provide home modifications to make his apartment physically accessible so that he can remain living there safely. Margot believes that some of her inpatient hospitalizations were potentially avoidable if she received additional home health aide services to address functional and self-care limitations resulting from cerebral palsy.

The stories presented in this report illustrate the time, energy, dedication, and patience required to obtain and coordinate the services necessary to ensure independent safe community living for seniors and people with disabilities. As a result of their experiences accessing HCBS, these individuals offer concrete ideas about how the system can be improved for others, such as:

- Simplifying the application process, which beneficiaries can find confusing and at times difficult to navigate. Specifically, beneficiaries envision a streamlined system through which seniors and people with disabilities can learn about and sign up at once for all of the various services that may be needed, including Medicaid HCBS, self-directed service options, subsidized housing, and transportation.

- Minimizing the number of times that applicants must “tell their story” and provide the same information again when seeking services.

- Providing easily accessible, accurate, timely updates about beneficiaries’ status, such as through a website, while waiting for services.

- Offering additional supports to beneficiaries who move inter-state to help navigate delays and additional barriers in arranging for the medically necessary care they need to transition to their new communities.

Despite some challenges, these stories confirm the essential role of Medicaid HCBS in improving beneficiaries’ daily lives by providing the physical and social functional supports necessary to access and benefit from community living. As these profiles make clear, seniors and people with disabilities have unique contributions to offer the communities in which they live, and Medicaid HCBS facilitate their integration into community life. For the beneficiaries profiled in this report and the many others who receive HCBS, Medicaid is a true safety net as it is often the only available source of these essential services to support community living.

Report

Curtis, Age 20, Topeka, Kansas

Medicaid attendant care services help young man with developmental disabilities improve independent living skills.

Medicaid attendant care services help young man with developmental disabilities improve independent living skills.

Curtis lives with his mother and legal guardian, Rhonda. He is diagnosed with autism, intellectual disabilities, and sensory integration issues. Curtis functions on the level of a 2nd to 3rd grader and has recently started to read. While he has a very easy-going personality, he cannot be left alone and needs help with shaving, bathing, and taking medication.

Curtis started receiving attendant care services through a Medicaid HCBS waiver about two years ago. His attendant accompanies him to the library, to get his hair cut, to community events, and to the book store where his favorite activity is looking at picture books. His attendant also helps him with basic life skills at home, such as making his bed and dusting his room. Rhonda locates, trains, and schedules Curtis’ attendants.

There is a desperate need for services for adolescents so that they can develop independent living skills in age-appropriate settings with peers.”

-Curtis’ mother, Rhonda

Rhonda says that attendant care services have enabled Curtis to interact with the community in an age-appropriate way as a young adult. She believes that receiving services earlier during adolescence would have helped Curtis develop greater independence at that time with getting his own breakfast or an after-school snack and getting on and off the school bus. Curtis was on the Medicaid HCBS waiver waiting list for 12 years, from ages six to 18, when Rhonda says they were in “desperate need” of services. As a single parent, Rhonda was able to work only because she found childcare providers who would supervise Curtis when he was a teenager; however, this arrangement meant that Curtis was with infants at a childcare center rather than in an age-appropriate setting with peers. Rhonda paid out-of-pocket about $50 per week for before- and after-school care and whenever she needed to go to an appointment or meeting by herself. Rhonda says that respite care at $25 per hour was unaffordable for her.

Looking ahead, Rhonda says that Curtis wants to continue to live with her, but eventually he will have to transition to a residential placement because she “will not live forever,” and he needs constant supervision. She hopes that he can move into a group home around age 25. She also would like him to attend a day program after he finishes high school at age 21, although that involves another waiting list. Rhonda describes the waiting list system as “confusing” and “a lot of work to orchestrate.” She found it difficult to learn how to get Curtis’ name onto the HCBS waiver waiting list and was frustrated during the wait because “no one can tell you where you are on the list.” Rhonda suggests that the system could be improved if people could look up their place on the list on a website while they are waiting for services.

Margot, Age 38, Charlotte, North Carolina

Home health aide services would support woman with cerebral palsy with working and living independently in the community.

Home health aide services would support woman with cerebral palsy with working and living independently in the community.

Margot has her master’s degree in social work and wants to be employed. However, since relocating from New York to North Carolina to live closer to family after a divorce, she has been unable to find a job because attending to her living and health care situation has taken up so much of her time. Margot has cerebral palsy and spastic quadriplegia. She can feed herself but needs help with preparing meals and all other activities of daily living, especially her morning and evening routines. Margot is dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare.

Although Margot started researching services before moving, she still has run into barriers. Most home health agencies said that she had to move first rather than getting services in place before relocating, as her disability requires. If Margot had not found an agency that was willing to work with her, she would have been stuck in New York. That agency estimated Margot would spend about four months on the HCBS waiver waiting list, so she decided to move and rent a room in a friend’s house because her family and friend thought that they could “make things work” temporarily. However, Margot has been on the waiting list much longer than anticipated, since April 2012.

A nursing facility would be a terrible alternative for my quality of life and would cost more than providing care at home.”

-Margot, age 38

Margot now receives 80 home health aide hours per month through the Medicaid state plan benefits package, which is less than the 66 home health aide hours per week that she received before moving. Her current hours are insufficient to meet all of her needs. Her family is now physically unable to provide most of her care, and Margot’s friend’s work obligations leave her friend unable to provide all the care Margot needs. Since moving, Margot has been hospitalized at least six times, some of which might have been avoided if she received more aide hours. The HCBS waiver would provide additional hours, but she has learned that the waiver waiting list can be as long as 15 years. There is also a separate two year waiting list for the program to self-direct services. Before relocating, Margot lived in her own apartment and could take her aide out to assist her while shopping for groceries or clothing. Currently, Margot is not permitted to do errands with her aide, which restricts her independence. Margot prefers to live on her own and does not want to live in a nursing home.

Transportation also is a challenge. Because Margot does not live within ¾ of a mile of a bus stop, she is placed on “standby” and does not learn if she will be picked up until the night before a scheduled trip. This is not workable because, she says, “the way my disability is, I have to plan ahead.” Another challenge is housing. Even if she were receiving enough home health aide hours to live on her own, the waiting list for a subsidized apartment is two to three years long. Margot learned about services “piecemeal” so she did not get onto all of the different waiting lists at the same time. She recommends that there should be a single place to find out about all services at once.

Irene, Age 79, Valrico, Florida

Medicaid HCBS will help daughter continue to care for mother with Alzheimer’s disease at home.

Irene has Alzheimer’s disease, and her condition has worsened significantly over the last six to 12 months. Irene needs help with dressing, preparing meals, and using the bathroom at night. She cannot be left alone and wakes up at night confused and crying. Irene lives with her 45 year old daughter, Julia, in a single family house. Julia moved from Colorado to Florida to care for her mother about five years ago. Julia says that “she’s not my mom anymore mentally,” but physically, Irene is healthy. Irene always was very independent, raising four children as a single mother. She was athletic well into her 60s, engaging in swimming, diving, tennis, softball, and whitewater rafting.

At this point, anything helps. . . in retrospect, I would have applied for services earlier rather than later.”

-Irene’s daughter, Julia

Irene has Medicare and is about to receive Medicaid, including 10 hours per week of in-home care. For the last six months, Julia has paid out-of-pocket for a companion aide, four hours a day, three days a week, to help with Irene’s care. However, Julia has concerns about her ability to continue to afford the companion aide because she left her job in Colorado to care for her mother full-time.

Julia says that her family always had talked about having Irene remain at home instead of going into a nursing home when Irene got older. Initially, Julia thought that she could handle Irene’s care but says that it has been very stressful, and her own health has deteriorated as a result – she has gained weight and her blood pressure has gone up. Julia’s plan is to keep Irene at home “as long as possible” but says that a lot depends on her continued ability to provide Irene’s care. Julia says that this has become increasingly difficult as Irene’s disease has progressed, and there is a “time when you want to give up.”Julia also believes that her mother now needs more care than the companion aide can provide. For example, Julia worries that Irene may start falling because she has started to “shuffle” while walking and is “wobbly.” Irene also has started wandering from the house. Julia installed door alarms, but recently Irene got out of the house, climbed over a fence, fell, and rolled down a slope in the front yard. Julia now needs to ask a neighbor to watch her mother while Julia walks her dog.

Julia started applying for Medicaid home and community-based waiver services for Irene about a year ago, after learning about the program at a local Alzheimer’s support group. She suggests that the application process could be streamlined to avoid the “exact same interview with three different people.” Julia says that she initially was “nervous” about applying for services because she thought that there were “probably people worse off” but now thinks that she was “in denial” about how difficult it had become for her to handle Irene’s care. Now that Irene has been approved for Medicaid HCBS, her case worker is “trying to rush things” to get services in place.

Mark, Age 43, Nashville, Tennessee

A group home placement would increase independence for working man with autism and ease the burden on his elderly parents.

A group home placement would increase independence for working man with autism and ease the burden on his elderly parents.

Mark has autism and intellectual disabilities. He has lived with his parents for his entire life. Mark’s mother, Jackie, always has been his primary caregiver, but it is becoming increasingly difficult for his parents to care for him now that they are getting older and developing their own health issues.

Mark has worked as a grocery store courtesy clerk for 12 years and enjoys having a “real job” outside of a sheltered workshop. He is very rigid about his daily schedule and will not deviate from his routine, such as the time he goes to bed, which can be difficult and limiting for his family. Jackie thinks that Mark probably could be more independent than he is. For example, he might be able to learn to get his own breakfast and do his own laundry. He bathes and dresses himself but needs help with shaving because he will not look into a mirror. He also will not talk on the telephone so his parents never leave him alone because he would be unable to call for help in an emergency. Jackie says that Mark needs 24/7 supervision, and ideally, she would like him to live in a small group home. She would like Mark’s move to happen while she is able to assist with his adjustment during the transition.

Receiving waiver services would give us a lot of peace of mind… I don’t want to be at a crisis point to receive services… I want to be able to help with the transition…”

-Mark’s mother, Jackie

Mark wants to live on his own because he wants to be like other adults his age, and Jackie says that he used to perseverate about having his own place to live. On the day of his initial interview for Medicaid waiver services, he stood in the driveway for a long time waiting for the caseworker to arrive. Now, Jackie feels that Mark has “sort of given up,” probably because he has been waiting for so long: Mark has been on the HCBS waiver waiting list for 20 years.

Mark is dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, but he is not currently receiving any HCBS due to the waiver waiting list. Jackie says that she has “no hope” of ever receiving waiver services because Mark’s case is not considered “urgent.” She receives an annual letter from the state confirming that Mark is still on the waiting list and asking if he still wants waiver services. She no longer calls the office because she says she “never get[s] any answers” and instead is “passed around from person to person.” Jackie does not even know who Mark’s caseworker is at this point. Jackie never expected to have to wait this long for services. She is frustrated and says she “has just about given up.”

Jackie also wishes that Mark had a social outlet and friends his age. She believes that moving to a residential placement would help Mark with this aspect of his life as well. She says that Mark only has his job and his family for social interaction now. Receiving Medicaid home and community-based waiver services “would make all the difference in the world” for Mark and his family and provide peace of mind for his parents.

Nicholas, Age 33, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Medicaid HCBS will make apartment physically accessible for man with multiple sclerosis.

Medicaid HCBS will make apartment physically accessible for man with multiple sclerosis.

Nicholas was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) at age 29, and the disease is advancing. He uses a motorized wheelchair and cannot walk more than a few feet. His hearing and vision are impaired, and he wears hearing aids. He also has difficulty using his hands and holding things. He receives a monthly drug infusion that reduces some symptoms. He recently developed a new symptom, trigeminal neuralgia (a nerve condition that causes intense facial pain), which he describes as “blindingly painful,” and for which he is taking a new medication. Nicholas says that he is in “a lot of pain” daily and has been “dealing with pain forever” as a result of MS.

Nicholas’s mother provides a lot of his care. She helps him with getting into bed, administering his medications, and putting lotion on his legs. She also does his laundry, cooking, and grocery shopping, and provides his transportation.

I would have waited as long as it took to get services.”

-Nicholas, age 33

Nicholas lives in an apartment with his mother that is physically inaccessible. His wheelchair does not fit through the bathroom doorway so he must transition out of his wheelchair to enter the bathroom, and the shower also is inaccessible. In September 2013, Nicholas had to go to the emergency room after he fell while home alone and trying to transfer from the bathroom to his wheelchair. His leg bent the wrong way, and he became wedged against the wall. He was screaming for help, but none of his neighbors was home at the time. His mother found him when she returned. He did not break any bones but says he had a long painful recovery.

Nicholas recently learned that he is about to start receiving Medicaid home and community-based waiver services. Nicholas already receives Medicaid state plan benefits, which cover his medications, doctor visits, and power wheelchair. He expects that the waiver will offer additional services, such as making his shower accessible, maintaining his power wheelchair, providing home-delivered meals, and supplying a car hook-up for his power wheelchair so that he can go out more easily in the community. Currently, he has a manual wheelchair that fits into his mother’s car but which is difficult for him to use as he needs someone to push him. As a result, he only goes where he “really need[s] to go,” such as doctor appointments.

Nicholas found out about the waiver from a friend and some internet research. When he learned that enrollment was capped, he initially decided to “set it aside.” Then, his therapist explained that there is a waiting list. Nicholas was on the waiting list about seven months. He was told that the wait might be a year or more so he was “excited” that the list moved more quickly. He is happy with his waiver case plan and hopes that the waiver will “clue [him] in to other services that may be available.”

Oscar, Age 11, and Aubrey, Age 19, Dalton, Georgia

Teenager overcame deficits in social interaction skills due to autism with the help of Medicaid HCBS, while waiting lists and an interstate move have delayed services for his brother.

Teenager overcame deficits in social interaction skills due to autism with the help of Medicaid HCBS, while waiting lists and an interstate move have delayed services for his brother.

Aubrey and Oscar are brothers who are both diagnosed with autism. They lived together with their parents in Georgia until their father’s job was transferred to Kansas in 2008. Both boys were receiving Medicaid HCBS in Georgia at that time, and because Aubrey was doing so well, the family decided to have him remain in Georgia, living with a relative, so he could continue to receive services and avoid the Medicaid HCBS waiver waiting list in Kansas. Although this meant that the family had to be separated, which was a hardship, Aubrey’s mother Angelina says that Aubrey “blossomed” socially as a result of the services he received. Medicaid HCBS provided Aubrey with opportunities to model typical peers and learn social and independent living skills. Aubrey also received eight hours of respite care per month through the waiver, which Angelina believes helped to keep her marriage intact as a result of the stresses associated with caring for children with disabilities. Aubrey improved to the point that he no longer qualified for special education services by the time he was a high school senior, and he is now in college majoring in mechanical drafting.

My two sons are very similar in terms of their functional abilities… Aubrey’s progress has been fantastic as a result of the services he received, while Oscar has languished on the waiting list…”

-Aubrey and Oscar’s mother, Angelina

Due to his young age, Oscar moved with his parents to Kansas, where his mother says he waited 4 ½ years for HCBS. As a result, Oscar has not had as many opportunities to develop social interaction skills, and the family has not had respite care, which has been stressful. Angelina also believes that Oscar could benefit from anger management therapy because he has not yet learned how to self-regulate his emotions.

Recently, the boys’ father lost his job, and the family returned to Georgia, where Oscar must start over again at the bottom of the HCBS waiver waiting list. Oscar has not yet been able to get onto the list because the family must provide a letter from a doctor in Georgia for his application to be considered complete. However, Angelina is unable to take Oscar to a doctor in Georgia until his application for Medicaid state plan services is approved, which can take up to 45 days. Angelina says that families of children with disabilities should be prepared to wait multiple years for services and worries that Aubrey and Oscar will have very different outcomes due to the different amount of services they each have received.

Mary A., Age 79, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Medicaid HCBS help senior with physical functional limitations continue to live independently in her own apartment.

Mary lives alone in a subsidized apartment building for senior citizens. She has diabetes, atrial fibrillation, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and was hospitalized for four days in February 2013 due to congestive heart failure. She had surgery for breast cancer in 2010, and continues to have follow-up tests. She sometimes has to use oxygen during the day because she gets out of breath when she “tries to do too much,” and she uses oxygen connected to a continuous positive airway pressure machine at night to keep her airway open. She also takes “a whole list” of medications and has frequent doctor appointments. Mary is dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare and receives Social Security benefits and food stamps.

I almost gave up and learned to do without while I was waiting for waiver services and unable to do things for myself.”

-Mary, age 79

Mary currently receives certified nursing assistant (CNA) services for an hour and 45 minutes a day, five days a week, and she recently learned that she will start receiving additional Medicaid home and community-based waiver services in two to three weeks. Presently, the CNA comes in the afternoons to help Mary with bathing and dressing. If there is any extra time, the CNA will help make her bed if she was unable to do so in the morning and fix her something to eat, but Mary says there is not much time for cooking because the CNA is there such a short time.

Mary needs help cleaning her apartment because she can no longer do any heavy work or lifting. She used to pay someone to help with cleaning, but she can no longer afford it. It is difficult for her to reach up to get a can down from the top shelf in her kitchen, and she also needs help grocery shopping. She says that the CNA used to be able to take her out for an “errand day” once a week, but CNAs are no longer permitted to do so. It is hard for Mary to find someone to take her shopping; when she does, she needs to pay the person about $20 for gas, and she doesn’t have much more than that to spend on her groceries. All of her money goes to rent, utilities, and food, and she can hardly afford anything extra like haircuts.

Mary says that she does not fully understand the Medicaid HCBS waiver program. She was on the waiting list for one year and was “about to give up.” Mary does not want to live in an assisted living facility or a nursing home and says that receiving Medicaid home and community-based wavier services will “make a whole lot of difference” in her life.

Patricia, Age 57, Logansport, Louisiana

Medicaid home health aide services would ensure that woman with multiple chronic conditions can remain safely at home.

Patricia lives alone in a two bedroom house. She is very hard of hearing and has advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, type II diabetes, high blood pressure, a left rotator cuff injury, and dizziness. She uses oxygen 24 hours a day and takes multiple medications. Patricia has had problems with retaining fluid and recently experienced facial numbness and a skin problem that required medication. She uses a wheelchair and worries about falling. When she has fallen in the past, someone has had difficulty helping her to get up.

“I don’t understand why Medicaid will pay for nursing facility care when it would be cheaper to have care in my home.”

-Patricia, age 57

Patricia presently receives a home nurse visit every two weeks to check her vital signs. Her ex-husband helps her with yard work and home repairs, but she still needs help with cleaning, changing her sheets, cooking, and showering. Patricia cannot stand for long periods of time and says that cooking, sweeping, or mopping “takes a lot out of [her].” When Patricia is alone, she eats sandwiches or microwaved meals. She also needs transportation to get to doctor appointments and the grocery store because she is physically unable to drive. One of her doctor’s offices is over an hour away, and she must pay someone to drive her there. She also would like companionship because she is mostly by herself and has no one with whom she can talk.

Patricia receives Social Security benefits, food stamps, Medicare, and Medicaid only to help with her Medicare out-of-pocket costs. Patricia has paid out-of-pocket for home health aide services in the past, but she only can afford to pay $90 for 12 hours of help per week, which people tell her is not enough money, and she has difficulty finding people who can reliably help her. She has to find friends or friends of friends through word of mouth to help her, and they are not trained. She would prefer to have services from someone who is properly trained and would know what to do if she fell.

Patricia’s initial application for Medicaid home and community-based waiver services was denied because she was told that she did not qualify for a nursing home level of care. However, she had difficulty hearing what was said because the assessment was done by phone. She thinks that the assessment should have been done in person in her home. She appealed the denial but also had difficulty understanding what was said during the telephone hearing. Finally, she called an advocate for help, and since July 2013, she has been on the waiver waiting list. At that time, she was told that there is a three year wait for services, and she has not had any subsequent updates about her status. Patricia was told that she could receive HCBS if she first went into a nursing facility, but she does not think that would make sense financially. She also fears that, if she were to go into a nursing facility, she would “never come home again.”

Ideally, Patricia would like to have home health aide services for four to six hours per day, three to four days per week. She says that she sometimes is concerned about her ability to continue to live at home and having Medicaid home and community-based waiver services would change her life “greatly” and would “make a big difference to [her].”

Mary B., Age 72, Kernersville, North Carolina

Medicaid HCBS enable senior with dementia to return home.

When Mary was diagnosed with dementia a couple of years ago, she decided to move into an assisted living facility. Since then, her dementia has worsened. Mary can remember her name and birth date and recognizes her daughter, Karen. She sometimes remembers the current date and day of the week. Mary also has renal failure, diabetes, and a history of high blood pressure and strokes. Mary uses a wheelchair if she needs to do a lot of walking, and at other times, she uses a walker. Mary is dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, which pay for her doctor visits and medications.

Waiver services help me take care of my mother better and make her life as comfortable and easy as possible.”

-Mary’s daughter, Karen

Some time ago, Mary asked Karen if she could return home to live with her. Karen agreed, and Mary spent about a year on the Medicaid HCBS waiver waiting list because services needed to be in place before she could move. During the time that Mary was waiting for services, Karen says that Mary was eager to come home. Karen felt badly because Mary would ask whether she could come home yet, and Karen would have to say no. Karen describes the wait as “kind of stressful.”

About two weeks ago, everything “fell into place,” and Mary was able to move into Karen’s apartment. The waiver provides 47 hours of home health aide services per week for Mary while Karen is at work. The aide helps Mary with preparing breakfast and lunch, dressing, and bathing. The waiver also paid for Mary’s bedside commode, bath bench, and wheelchair and provides supplies, such as pull-ups. Mary is currently on a waiting list for home-delivered meals, and Karen was told that that wait will be about a month. Karen also is looking into a day program for Mary through the waiver.

Karen believes that Mary is receiving better care at home than she did in the assisted living facility. She feels that the home health aide provides Mary with “more one-on-one attention” and that Mary is “receiving the correct attention” at home. At the assisted living facility, Mary had some falls, including one resulting in a bad gash on her forehead, because no one was around to watch her or help her use the bathroom.

Karen takes Mary out to family dinners and trips to the zoo. They spend a lot of time sharing stories and jokes and doing crossword puzzles with each other and Mary’s aide. Besides the services provided by the waiver, Karen provides additional care for Mary. She takes her to the bathroom every two hours overnight, helps with her personal hygiene, prepares her dinner, and helps get her ready for the day. Karen says that she is happy to have her mother at home because she gets to spend more time with her, and having waiver services has made Mary’s return home possible.

Endnotes

Introduction

See generally Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Five Key Facts About the Delivery and Financing of Long-Term Services and Supports (Sept. 2013), available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/five-key-facts-about-the-delivery-and-financing-of-long-term-services-and-supports/.

For additional examples of HCBS, see Victoria Peebles and Alex Bohl, CMS/Mathematica Policy Research, The HCBS Taxonomy: A New Language for Classifying Home and Community-Based Services (Aug. 2013), available at http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/publications/PDFs/health/max_ib19.pdf?spMailingID=7043783&spUserID=MTg0ODk4MzU1MwS2&spJobID=90194295&spReportId=OTAxOTQyOTUS1.

See 42 U.S.C. § 1396n (j), (k).

Pseudonyms have been used at an individual’s request.

Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services Programs: 2010 Data Update (March, 2014), available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-home-and-community-based-service-programs/. These figures reflect enrollment and expenditures for Medicaid state plan home health and personal care services and § 1915(c) waivers. States also may provide Medicaid HCBS through § 1115 waivers, the Balancing Incentive Program, the Community First Choice state plan option, and § 1915(i).

For more information, see Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Long-Term Services and Supports: An Overview of Funding Authorities (Sept. 2013), available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/medicaid-long-term-services-and-supports-an-overview-of-funding-authorities/.

Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services Programs: 2010 Data Update (March, 2014), available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-home-and-community-based-service-programs/.

Id.

Olmstead v. L.C. 527 U.S. 581 (1999), available at http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/98-536.ZS.html.