How the ACA Changes Pathways to Insurance Coverage for People with HIV

There are multiple sources of insurance coverage and care for people with HIV in the United States. These include public programs, such as Medicaid and Medicare, and the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program, as well as private coverage through an employer or in the individual market. Medicaid, the nation’s principal safety-net health insurance program for low-income Americans, is estimated to cover the largest share of people with HIV. Fewer are covered by Medicare, the federal health insurance program for people age 65 and older and younger adults with permanent disabilities, or have private insurance, and a significant share is uninsured, relying primarily on Ryan White, the nation’s single largest federal grant program designed specifically for people with HIV who are uninsured or underinsured, and operating as the “payer of last resort.” Eligibility for these different coverage sources depends on numerous factors, including state of residence, income, employment and health status, age, and citizenship. As a result, the current system of coverage for people with HIV is a complex patchwork that leaves some outside the system and presents others with barriers to needed access.

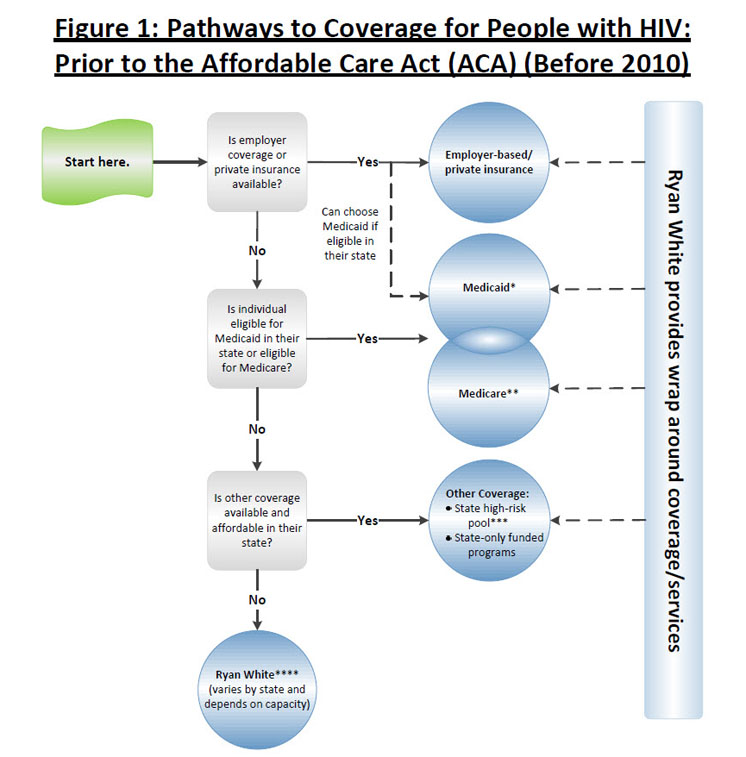

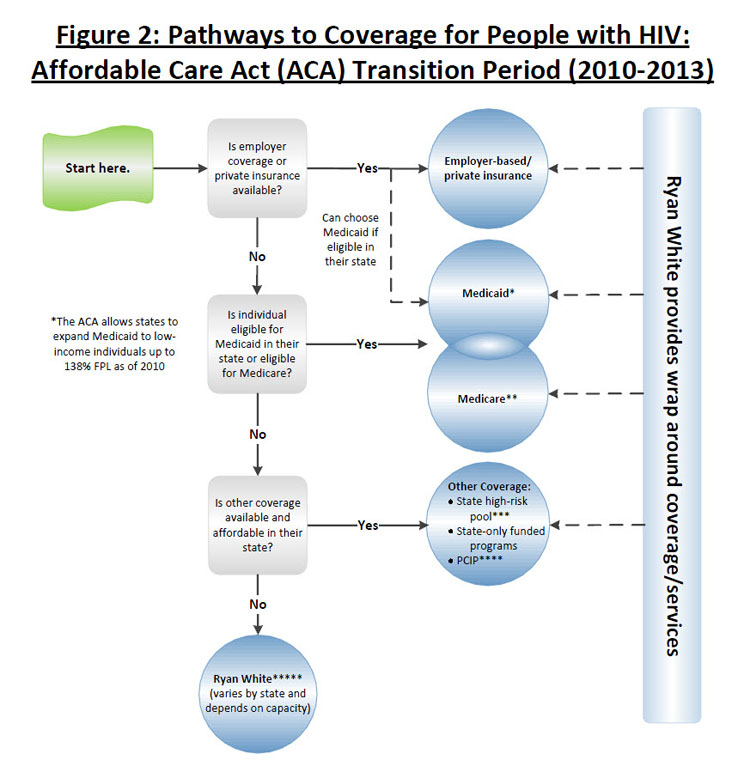

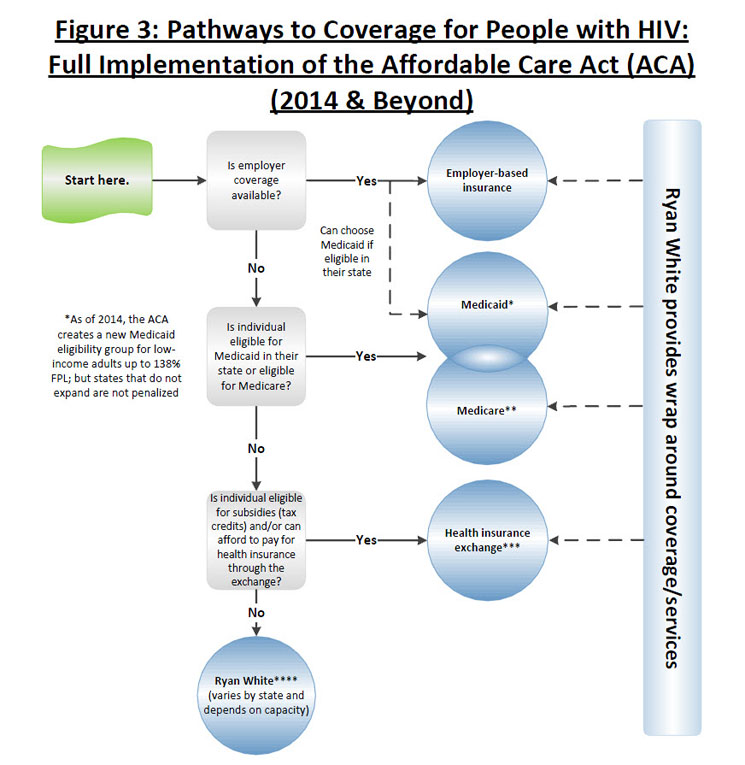

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), passed in 2010, will expand insurance coverage, and therefore access to care, for millions of people in the U.S., including people with HIV. Some of the ACA’s provisions went into effect soon after the law was passed; most that affect coverage will go into effect in 2014. Access to care, particularly antiretroviral treatment (ART), is not only critical for the health of people with HIV, it also carries important public health benefits with recent research demonstrating that ART significantly reduces the risk of HIV transmission from an HIV positive to negative individual. A new series of infographics developed by Kaiser depicts the pathways to insurance coverage for people with HIV, prior to the ACA, after the ACA was enacted but before 2014, and as of 2014 and beyond. As they indicate, coverage options have already expanded for people with HIV and are expected to expand further in 2014, although coverage will continue to vary across the country.

Prior to the ACA (before 2010)

Employer-sponsored coverage (ESI) is the primary way in which most people in the U.S. obtain health insurance coverage, although studies indicate that this is less so for people with HIV. Those without access to ESI could attempt to purchase coverage in the individual, non-group market. However, prior to the passage of the ACA, many people with HIV were effectively shut out of the individual market either because HIV was considered an uninsurable, pre-existing, condition by insurers or, if available, was often unaffordable. Medicaid, Medicare, and other public programs, therefore, were important pathways for people with HIV. To be eligible for Medicaid, an individual has to meet the income criteria in their state and belong to a group that was “categorically eligible” (children, parents with dependent children, pregnant women, and individuals with disabilities), and most people with HIV qualify on the basis of being both low-income and disabled. Prior to the ACA, federal law categorically excluded non-disabled adults without dependent children from Medicaid, unless a state obtained a waiver or used state-only dollars to cover them. This presented a barrier, and a “Catch-22,” to many low-income people with HIV who could not qualify for the program until they were disabled, despite the fact that Medicaid covers medications that stave off HIV-related disability and reduce mortality. To be eligible for Medicare, an individual has to be age 65 or older or, if under 65, permanently disabled. If not eligible for Medicare or Medicaid, a person with HIV might have access to state-funded coverage, such as a high risk pool, available in some states, but ultimately, would likely need to rely on the Ryan White program. In addition, Ryan White often “wrapped around” other forms of coverage, including Medicaid and Medicare, providing supplemental services where needed.

>>View full-size version and notes (.pdf)

ACA Transition Period (2010-2014)

The ACA provided additional coverage options in 2010. In the private insurance market, the ACA established a temporary program in every state to allow people with pre-existing medical conditions, such as HIV, who had been uninsured for six months or more and denied insurance coverage to purchase coverage through a Pre-Existing Condition Insurance Plan (PCIP). It also prohibited individual and group health plans from placing lifetime limits on coverage, thereby preventing people with very expensive illnesses from running out of coverage, and extended dependent coverage for adult children up to age 26 in all individual and group plans. In addition, the ACA created a new state Medicaid option for states to cover childless adults with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) in their Medicaid programs, which several states have already used. Still, even with these expanded options, people with HIV who remain ineligible for coverage, or face limits in their coverage (e.g., benefit limitations), continue to rely on Ryan White.

>>View full-size version and notes (.pdf)

Full Implementation of the ACA (2014 & Beyond)

Most of the ACA’s coverage expansions go into effect in 2014. As of 2014, the ACA requires U.S. citizens and legal residents to have qualifying health coverage, and provides additional insurance market protections, cost-sharing, and coverage options to facilitate coverage. Health insurers will no longer be able to deny coverage to people with pre-existing health conditions (and the temporary PCIPs will no longer be needed). They will also be prohibited from placing annual limits on coverage and be required to guarantee issue and renew health insurance regardless of health status. Individuals will be able to purchase coverage through state-based “Health Insurance Exchanges” and depending on income, people without access to affordable ESI will be eligible for premium and cost-sharing subsidies to purchase coverage in the exchange. Finally, as of 2014, the ACA establishes a new Medicaid eligibility category for citizens and legal residents with incomes up to 138% FPL (thereby removing the categorical eligibility requirement and basing Medicaid eligibility solely on income) and provides states with an enhanced federal matching rate for this population. While a new mandatory eligibility category was established under the law, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in June 2012 that states could not be penalized if they did not expand coverage to this new group, and it is therefore uncertain if all states will comply with this requirement.

>>View full-size version and notes (.pdf)

The ACA has already led to improvements in access to and quality of care for people living with HIV and, when fully implemented in 2014, is expected to significantly expand access even further. Still, there are several outstanding questions, including: Will states go forward with the Medicaid expansion and provide coverage to a significant number of people who are HIV positive? Will the benefits package available through Medicaid and the Exchange be sufficient for people with HIV? And, how might the Ryan White program be changed or restructured when it comes up for reauthorization next year, filling in gaps for those who are ineligible for other coverage or still face high cost-sharing for drugs and other health care services?