Medical Debt Among Insured Consumers: The Role of Cost Sharing, Transparency, and Consumer Assistance

A recent report issued by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) finds that medical debts account for a majority (52%) of debt collections actions that appear on consumer credit reports. This report offers yet another reminder that a broader view of health insurance – not just at how many have coverage, but also the effectiveness of coverage – is warranted. An earlier Kaiser Family Foundation report found that 1 in 3 Americans struggle to pay medical bills, and that 70% who do so are insured.

The CFPB report confirms that medical debt frequently occurs among people with no other history of credit problems. When it does, it can have serious and long range financial consequences. Referral of medical debts to collections damages a person’s credit rating significantly and for many years, limiting access to mortgages, car loans, and other consumer credit. Health consequences are also possible; as the Kaiser report observed, once in debt, people may delay or forego other needed care to avoid incurring further unaffordable medical bills.

Medical debt and high cost sharing

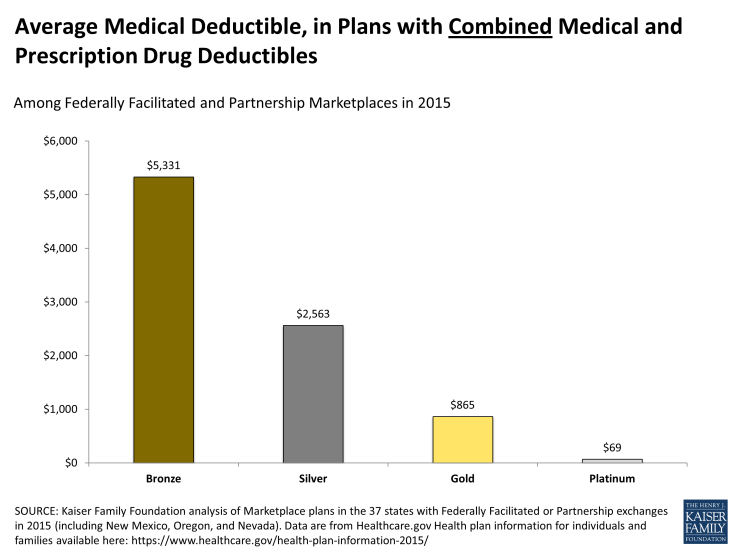

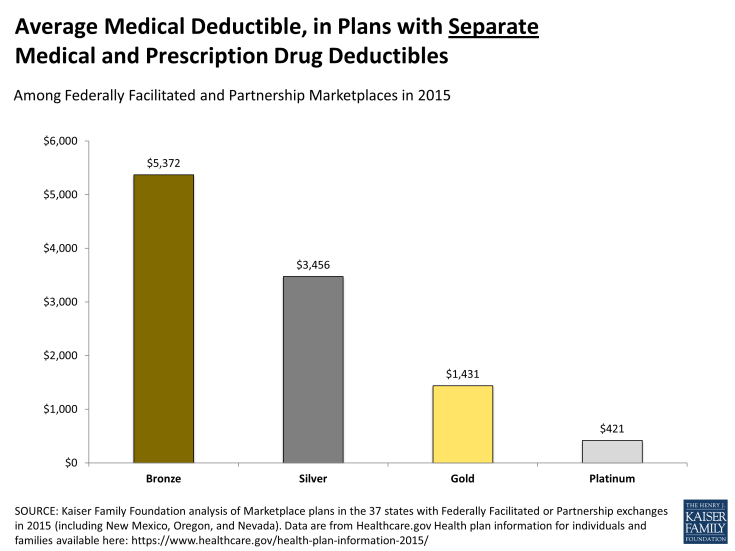

How is it that medical debt can be so prevalent among the insured? The Kaiser report observed that cost sharing is one primary contributor. Cost sharing levels under many health plans now exceed the resources that most families have on hand. In its most recent report on the economic well-being of US households, the Federal Reserve found that only 48 percent of Americans would be able to completely cover a hypothetical emergency expense costing $400 without selling something or borrowing money. Unforeseen medical expenses could trigger such an emergency – though under most health plans today, consumer’s cost liability could be much greater than $400. The average annual deductible – the amount a patient must pay out of pocket before health insurance reimbursement begins – under job-based health plans exceeded $1,200 for an individual in 2014. For non-group health plans sold on new health insurance marketplaces, deductibles are even higher. For silver plans (the most popular plan type in 2014) offered in federally administered marketplaces, the average annual medical deductible in 2015 is $2,563 for plans with a combined medical/prescription drug deductible; in silver plans with separate medical and drug deductibles, the average annual medical deductible is $3,456. (In the 37 federally facilitated and partnership marketplaces in 2015, 55% of silver plans feature a combined annual deductible while 45% of silver plans apply separate annual deductibles for medical and prescription drug expenses.) For less expensive bronze plans, the average annual deductible exceeds $5,300 in 2015. Some policymakers have discussed the option of making available so-called copper plans, which would have even higher cost sharing. Under the ACA, cost sharing subsidies are available to low income consumers up to 250% of the federal poverty level.

Out of pocket medical spending can exceed the amount of the deductible in a year for insured consumers who have a major health event, such as surgery. Additional copays and coinsurance can apply after the deductible, up to an annual out-of-pocket limit. That limit was $6,350 ($12,700 for family coverage) in 2014, increased to $6,600/$13,200 in 2015 and proposed to increase to $6,850/$13,700 in 2016. This limit applies to all non-grandfathered health plans, including those offered by employers. However, guidance issued earlier this year by the U.S. Department of Labor suggested that employers may have flexibility to define which covered benefits are subject to the out of pocket limit, leaving consumer cost sharing for other covered, in-network benefits to apply without limit.

The Kaiser report noted other reasons why insured consumers accrue medical debt, including receipt of care from providers outside the health plan network. The ACA sets network adequacy requirements for Marketplace plans.

Medical debt and complexity/lack of transparency

The CFPB report also noted that the problem of medical debt and collections may be exacerbated by complexity and lack of transparency:

“In particular, the complexity of medical billing and the third-party reimbursement processes faced by most patients and their families is a potential source of confusion or misunderstanding between patient, medical provider, and insurer. That complexity could lead some consumers to be unaware of when, to whom, or for what amount they owe a medical bill or even whether payment was the responsibility of the consumer rather than an insurance company.”

A recurring theme observed in the Kaiser report was that consumers were often surprised to learn how much they owed for care they thought would be covered by insurance.

The ACA provides for development of new tools to make health insurance coverage more understandable and transparent for consumers. One such tool is the summary of benefits and coverage (SBC) – a short, standardized summary of what a health plan covers and how cost sharing applies to each major benefit. All non-grandfathered health plans are required to provide an SBC to all enrollees and make it available to prospective enrollees. The SBC is to be written in plain language with no fine print. It must also include standardized scenarios to illustrate how the plan would cover common medical events and what out of pocket expenses might be left for consumers. By comparing these “coverage illustrations,” consumers can discern differences in the relative comprehensiveness of coverage under plan choices. A 2011 Kaiser survey found the SBC to be the single most popular provision under the ACA. To date, however, implementation of this requirement has been incomplete. Insurers are currently required to provide only two of the six coverage illustrations provided for under the implementing regulation; a recent proposed amendment to the regulation would add a third illustration. In addition, to generate SBC coverage illustrations, insurers and health plans have been permitted to use a short cut calculator that doesn’t take into account potentially important plan features (such as brand vs. generic cost sharing differences) that could impact a patient’s relative cost sharing responsibility under different plans. An analysis of the calculator’s results observed that over-simplifying the process can mask important plan differences for consumers and cloud transparency. Initially insurers were allowed to use the short cut for one year, but that flexibility has since been extended indefinitely.

Initial regulations to implement new appeal rights under the ACA also established new standards for the explanation of benefits (EOB) statement that summarizes what claims have been paid or denied. The initial regulation required that specific information about each claim, including billing codes, should be included to help consumers identify the service in question. An amendment to the appeals regulation subsequently removed this requirement in favor of a more general claims description.

The ACA also requires other transparency reporting by all non-grandfathered health plans, including those sponsored by employers. Plans are to periodically report data on enrollment, disenrollment, claims payment practices, claims denials, out of network claims and associated consumer expenses, and any other information deemed appropriate by the Secretary. Data are to be used to facilitate oversight and enforcement and to develop plan rating tools to inform consumers. This broad data reporting authority could also be used to make billing and payment practices more transparent. To date, implementation of this ACA transparency provision has not been initiated.

Medical Debt and Consumer Assistance

Finally, the Kaiser report observed how consumers can be confused and overwhelmed by jargon and the sheer volume of medical bills and insurance statements, particularly when they are sick. The ACA authorizes funding for ombudsman or consumer assistance programs (CAPs) to be established in each state. CAPs are required to serve all state residents – those in group health plans, non-group plans, and the uninsured. CAPs are to help consumers answer questions about their coverage, resolve disputes, and file appeals. CAPs also are to help consumers explore coverage options for which they are eligible and apply for subsidies. And, CAPs are to collect data on consumer experiences with health plans and report it to the Secretary who, in turn, is to use CAP data to inform oversight and strengthen enforcement. During the first year of implementation (2010-2011), 38 state CAPs provided assistance to more than 200,000 individuals and helped them recover more than $18 million in benefit payment. Since then, no new CAP appropriations have been legislated and the number of active programs has declined. Insurers and group health plans are required by the ACA to include notice about CAP assistance on all denial letters. Group plans must provide such notice to participants living in states listed on a DOL web site.

Conclusion

Increasing deductibles and other cost sharing have helped to make insurance premiums more affordable, but the flip side has been to expose even people with insurance to risk of medical debt. When cost-sharing under health insurance exceeds the ability of consumers to pay their medical bills, cases of health-related bankruptcy and credit problems are inevitable. Greater transparency in the details of health insurance plans cannot eliminate medical debt, but they can help consumers distinguish plan differences to make more informed choices and to plan ahead financially. Greater transparency, as well as consumer assistance, can also help consumers use their coverage more effectively and resolve billing questions and disputes when they arise.