The U.S. Response to Ebola: Status of the FY2015 Emergency Ebola Appropriation

Overview

The Ebola outbreak of 2014 was a global wake-up call regarding the ongoing threat of emerging infectious diseases. After a slow initial response by the global community, including the U.S. government, the U.S. mounted what has become the largest effort by a single donor government to respond to Ebola. This includes an emergency appropriation of $5.4 billion by Congress as part of its final FY 2015 spending package, a funding amount significantly larger than previous emergency response efforts to address emerging infectious disease outbreaks such as SARS and avian influenza.1,2 Since this funding was designated by Congress as an emergency funding measure, it did not count toward existing budget caps on discretionary spending.

Today, a year later, as Ebola case numbers have dropped and countries have been declared Ebola-free, the emergency response has been winding down and a transition period toward more sustained support for health systems in the region and other vulnerable areas has begun. Given the large U.S. investments for Ebola, including approximately $2.0 billion that has been obligated by the U.S. for the international response effort, now is an opportune time to examine where the U.S. response stands.3,4 What specifically was funding provided for and what is its current status? How is U.S. funding being used to address the outbreak and its aftermath, and prepare for future health threats? How available and transparent is information about these activities? This issue brief seeks to shed light on some of these issues, focusing on the $5.4 billion emergency Ebola funding and providing an overview of its international activities, the agencies carrying out these activities, and the status of funding to date.

Introduction

The West African Ebola outbreak in 2014 caught most of the world by surprise. Although the first cases were identified as far back as March 2014,5,6 the initial response to these early cases was slow and inadequate, and over the summer and fall of 2014 case numbers rose dramatically in the three most affected countries of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. By the summer of 2014 the region was experiencing devastating rates of transmission, as high as a thousand new cases every week.6,7 Since that time, transmission of the disease has been almost entirely interrupted. Overall, there have been over 28,000 cases and 11,000 deaths in this outbreak, making it by far the deadliest Ebola outbreak ever.6

As case numbers began to rise in West Africa last year, the United States response was initially delayed and slow to ramp up, but by August 2014 the U.S. government had begun to mount what has become the largest effort by a single donor government to respond to Ebola, a response that has included marshalling financial resources, personnel, and technical expertise. Notably, this included an emergency funding request by the Obama Administration in November 2014 for $6.2 billion.8 Eventually Congress appropriated $5.4 billion in emergency Ebola funding in December 2014, most of which was to be directed to international activities.1 This was significantly larger than previous emergency response funding provided by Congress to address an emerging disease outbreak such as SARS and avian influenza.2

As Ebola case numbers have dropped and countries have been declared Ebola-free, the emergency response is now transitioning toward more sustained support for health systems in the region, including a planned five-year effort through the Global Health Security Agenda to bolster the capacity of countries across sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere to prevent, detect, and respond to future outbreaks and other emerging health threats.9

Given the large U.S. investments for Ebola in the region, this brief reviews where the U.S. response stands. What specifically was funding provided for and what is its current status? How is U.S. funding being used to address the outbreak and its aftermath, and prepare for future health threats? How available and transparent is information about these activities? This issue brief seeks to shed light on some of these issues, focusing on the $5.4 billion emergency Ebola funding and providing an overview of its international activities, the agencies carrying out these activities, and the status of funding to date.

Background

U.S. efforts to respond to emerging and infectious diseases (EIDs), such as Ebola, are conducted through multiple departments and agencies that oversee both ongoing and emergency programs in both domestic and international settings. Ongoing programs receive funding each year from Congress through the annual appropriations process and primarily support efforts to detect and prevent outbreaks, although, this funding may also be used for emergency response efforts should an outbreak occur. Separately, Congress also provides annual funding for emergency and disaster assistance efforts that can be utilized to respond to emergencies, including health emergencies, such as the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. In addition to these ongoing programs and the support for emergency situations, the USG provides funding for EID-related research activities through the National Institutes of Health (NIH).10

During the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, U.S. government activities to combat the growing epidemic were initially funded using regular appropriations already available at the civilian agencies, particularly the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), for ongoing EID programs and emergency and disaster response efforts. The U.S. military was also involved in the response, and the Department of Defense (DoD) initially funded its Ebola response activities through existing appropriations, but eventually sought and received permission from Congress to transfer funding from its Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) account to support its West Africa operations as its engagement grew in scope.11

It is estimated that initial response funding from U.S. agencies totaled more than $770 million prior to passage of the emergency Ebola appropriation, most of which was provided by USAID.12 As the outbreak worsened and it became apparent that a larger response was necessary to both control further spread and recover from its impacts, the President sent an emergency funding request to Congress.8

Emergency Ebola Funding

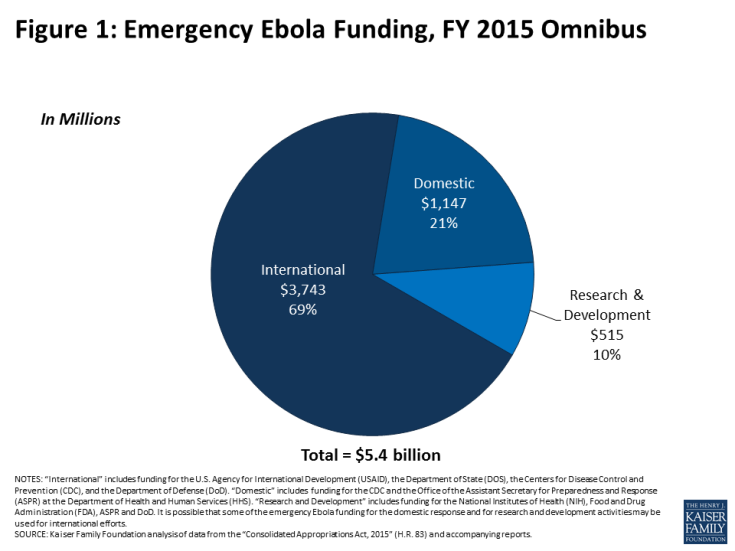

On November 5, 2014, President Obama sent an emergency funding request to Congress for $6.2 billion to support the Ebola response and recovery effort.8 When Congress finalized appropriations for FY 2015 in December 2014, it included $5.4 billion, almost the entire amount, in emergency Ebola funding (see Table 1).1,13,14 Of the $5.4 billion Congress provided, approximately $3.7 billion, or more than two thirds (69%), was designated for international efforts, $1.1 billion (21%) for the domestic response, and $515 million (10%) for research and development activities (see Figure 1). The research and development funding could be used in either domestic or international settings. Additionally, it is possible that some of the domestic funding could be used for international efforts.

| Table 1: Emergency Ebola Funding – FY15 Omnibus (millions) | ||

| Agency / Department / Account | Total Funding | Expenditure Period |

| International Response | ||

| Department of State | $41.7 | – |

| Diplomatic & Consular Programs | $36.4 | “to remain available until September 30, 2016” |

| International Security Assistance | $5.3 | “to remain available until September 30, 2016” |

| USAID | $2,484.7 | – |

| Operating Expenses | $19.0 | “to remain available until September 30, 2016” |

| Office of Inspector General | $5.6 | “to remain available until expended” |

| Global Health Programs (GHP) account | $312.0 | “to remain available until expended” |

| International Disaster Assistance (IDA) account | $1,436.3 | “to remain available until expended” |

| Economic Support Fund (ESF) account | $711.7 | “to remain available until September 30, 2016” |

| Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) | $1,200.0 | “to remain available until September 30, 2019” |

| Department of Defense (DoD) | $17.0 | – |

| Equipment Procurement | $17.0 | “to remain available until September 30, 2017” |

| Total International Response | $3,743.4 | – |

| Research and Development | ||

| Health and Human Services (HHS) | $420.0 | – |

| National Institutes of Health (NIH) | $238.0 | “to remain available until September 30, 2016” |

| Biomedical Advanced Research and Development (BARDA) | $157.0 | “to remain available until September 30, 2019” |

| Food & Drug Administration (FDA) | $25.0 | “to remain available until expended” |

| Department of Defense (DoD) | $95.0 | – |

| Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) | $45.0 | “to remain available until September 30, 2016” |

| Chemical and Biological Defense Program (CBDP) | $50.0 | “to remain available until September 30, 2016” |

| Total Research and Development | $515.0 | – |

| Domestic Response | ||

| Health and Human Services (HHS) | $1,147.0 | – |

| Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) | $571.0 | “to remain available until September 30, 2019” |

| Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) | $576.0 | “to remain available until September 30, 2019” |

| Total Domestic Response | $1,147.0 | – |

| Total Ebola Funding | $5,405.4 | – |

| NOTES: The emergency funding for Ebola does not count towards overall budget caps. Research and development funding may be used for either domestic or international efforts. It is also possible that some of the $1.1 billion for the domestic response may be used for international efforts. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the “Consolidated and Further Appropriations Act, 2015” (P.L. 113-235) and associated explanatory statements. |

||

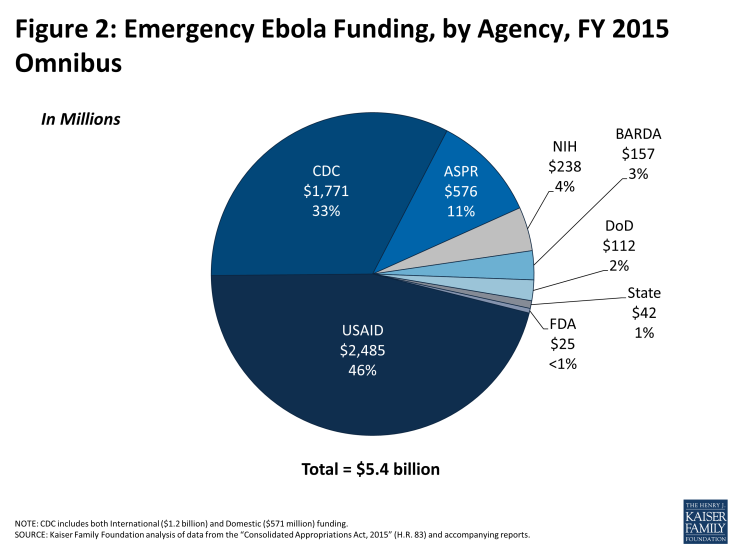

The majority of the $3.7 billion specified for the international response effort was provided to USAID ($2.5 billion), followed by the CDC ($1.2 billion, of which $597 million is designated to support national public health institutes and global health security), the State Department ($42 million), and DoD ($17 million).15 Of the $1.1 billion that was designated for domestic purposes, $576 million was provided to the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and $571 million was provided to the CDC (it is possible that some of the domestic funding could be used for international purposes). Of the $515 million in research and development funding, which could be used in either domestic or international settings, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) ($238 million) accounted for the largest amount, followed by the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development (BARDA) program at HHS ($157 million), DoD ($95 million), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ($25 million) (see Figure 2).

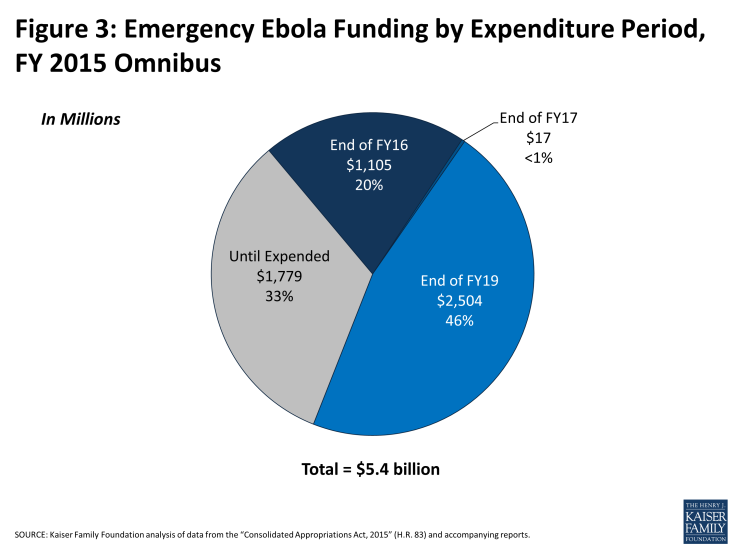

In the appropriations bill, Congress stipulated that the emergency Ebola funding could be used to reimburse previous expenditures/accounts. According to USAID, all of the funding they had already spent to respond to Ebola in 2014 was “back-filled” by the emergency Ebola appropriation; it is not yet known whether other departments and agencies involved in the response also used the emergency appropriation to reimburse prior activities. In addition, the bill specified that funding could be disbursed over a multi-year period, although the periods vary by agency and account. For instance, Congress specified that the funding provided to the CDC ($1.8 billion, of which $1.2 billion is for international efforts) would remain available through FY19, while the majority of the $2.5 billion provided to USAID would “remain available until expended” (see Figure 3). Overall, $1.1 billion (20%) was provided as two-year funding, $17 million (less than 1%) as three-year funding, $2.5 billion (46%) as five-year funding, and $1.8 billion (33%) until expended. Congress also included specific reporting requirements on how the emergency funding was being utilized. For instance, USAID is required to report monthly, while HHS is required to report quarterly. These reports, however, are not publicly available at this time.

International Activities Supported by the Emergency Ebola Funding

The overarching goals for the emergency funding, as described in the President’s request to Congress, were to “fortify domestic public health systems, contain and mitigate the epidemic in West Africa, speed the procurement and testing of vaccines and therapeutics, and…enhancing capacity for vulnerable countries to prevent disease outbreaks, detect them early, and swiftly respond before they become epidemics that threaten our national security.”8 When it approved the emergency Ebola appropriation, Congress provided direction to each agency receiving funding as to the kinds of activities to be supported with this funding as follows (see Table 2):

- USAID was named the lead agency for the Ebola response, and Congress directed emergency funding to the agency to support a variety of activities including immediate disaster assistance and humanitarian response needs in the highly affected countries. Such activities ranged from the establishment of Ebola treatment units and community care facilities; provision of supplies such as personal protective equipment; community outreach, communication and mobilization efforts; and logistics support. USAID was also directed to use the funding to address the secondary economic and social impacts of the outbreak, from food insecurity to economic stabilization and security.

- The Department of State was provided funding to assist countries to “prevent, prepare for, and respond” to Ebola, and to “promote biosecurity practices” and “mitigate the risk of illicit acquisition of the Ebola virus.”

- CDC was named the medical lead for the international response, and directed by Congress to use the funding to help countries prevent, prepare for, and respond to the Ebola outbreak through activities such as infection control, contact tracing and laboratory surveillance and training; building up emergency operation centers; and providing education and outreach. CDC has also been involved in the conduct of clinical trials in affected countries to assess the safety and efficacy of vaccine and treatment candidates.

Likewise, Congress identified some funding to go to agencies for the purpose of research and development of vaccines, treatments, and other medical technologies for addressing Ebola.

- NIH received funding to help advance clinical trials on the safety and efficacy of Ebola vaccines and therapeutics.

- BARDA was directed to use its funding to develop medical countermeasures such as vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, and medical supplies.

- The Department of Defense was provided emergency funding for clinical trials for vaccines and treatments, and for Ebola diagnostic development.16

- The FDA was provided funding to help develop these countermeasures and provide oversight during review of the products and the post-market surveillance of these products.

Many of these activities remain in progress and in some cases have not yet even begun, as some agencies have multiple-year time frames to utilize the funds. As mentioned above, while Congress required reports from agencies detailing progress on these activities and the funds that have been expended to date, these reports have not yet been made public. Therefore, a clear and comprehensive accounting of what has been spent, and for which activities, is not yet available. This includes a lack of information about which activities supported the initial response and which are supporting ongoing transition and recovery efforts as well as more general health system strengthening.

| Table 2: Activities Supported by the Emergency Ebola Funding | |

| Agency / Department / Account | Total Funding |

| International Response | |

| Department of State | – |

| Diplomatic & Consular Programs | To prevent, prepare for, and respond to the Ebola outbreak |

| International Security Assistance | Mitigate the risk of illicit acquisition of the Ebola virus and to promote biosecurity practices associated with Ebola |

| USAID | – |

| Operating Expenses | To prevent, prepare for, and respond to the Ebola outbreak |

| Office of Inspector General | Oversight of Ebola activities |

| Global Health Programs (GHP) account | To prevent, prepare for, and respond to the Ebola outbreak in countries directly affected by, or at risk of being effected by, Ebola |

| International Disaster Assistance (IDA) account | Assistance for countries affected by, or at risk of being affected by, Ebola |

| Economic Support Fund (ESF) account | To prevent, prepare for, and respond to the Ebola outbreak and to address economic and stabilization requirements resulting from an outbreak |

| Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) | To prevent, prepare for, and respond to the Ebola outbreak internationally |

| Department of Defense (DoD) | – |

| Equipment Procurement | Equipment for detection and diagnostic systems, mortuary supplies, and isolation transport units |

| Research and Development | |

| Health and Human Services (HHS) | – |

| National Institutes of Health (NIH) | To prevent, prepare for, and respond to Ebola domestically and internationally |

| Biomedical Advanced Research and Development (BARDA) | To prevent, prepare for, and respond to Ebola domestically and internationally, and to develop necessary medical countermeasures and vaccines including the development and purchase of vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics, and necessary medical supplies and administrative activities |

| Food & Drug Administration (FDA) | For an additional amount for “Salaries and Expenses”, to prevent, prepare for, and respond to the Ebola virus domestically and internationally, and to develop necessary medical countermeasures and vaccines, including the review, regulations, post market surveillance of vaccines and therapies, and administrative activities |

| Department of Defense (DoD) | – |

| Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) | Clinical trials for vaccines and treatments for Ebola |

| Chemical and Biological Defense Program (CBDP) | Develop vaccines, treatments, and diagnostic systems for Ebola |

| Domestic Response | |

| Health and Human Services (HHS) | – |

| Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) | To prevent, prepare for, and respond to the Ebola outbreak domestically |

| Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) | For the renovation and alteration of privately owned facilities to improve preparedness and response capabilities and to reimburse domestic transportation and treatment costs for individuals treated in the US. |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the “Consolidated and Further Appropriations Act, 2015” (P.L. 113-235) and associated explanatory statements. | |

Status of Ebola Funding

Data on the status of the emergency Ebola funding are limited. Some data are available from USAID, which has released regularly updated factsheets providing information on the international response effort and funding amounts obligated by USAID, CDC, and DoD, and from the Office of Inspector General (OIG) at USAID, which has released Congressionally mandated quarterly reports on the U.S. government’s international Ebola response and preparedness efforts. To date, the Department of State (DOS), USAID, CDC, and DoD report that they had obligated approximately $2.0 billion in total international funding towards the Ebola outbreak (see Table 3).3,4 USAID accounted for the largest amount ($1.2 billion), followed by the DoD ($474 million), CDC ($364 million), and the DOS ($32 million). An additional $523 million ($365 million through HHS and $158 million through DoD) has been obligated for research and development activities, but this funding could not be disaggregated by international or domestic purposes. In addition, the status of domestic funding is not currently known.

| Table 3: Total U.S. Ebola Funding for the International Response (FY 2014 – FY 2016)3,4 | |

| Agency | Total Funding (in millions) |

| International Response | |

| Department of State (DOS) | $32.1 |

| Diplomatic & Consular Programs | $22.1 |

| International Security Assistance | $5.0 |

| Economic Support Fund (ESF) | $5.0 |

| U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) | $1,158.8 |

| Operating Expenses | $3.0 |

| Office of the Inspector General (OIG) | $1.9 |

| Global Health Programs (GHP) | $159.2 |

| International Disaster Assistance (IDA) | $869.8 |

| Economic Support Fund (ESF) | $124.8 |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) | $364.5 |

| Department of Defense (DoD) | $473.8 |

| Equipment Procurement | $14.3 |

| Overseas, Humanitarian, Disaster Assistance, & Civic Aid | $406.4 |

| Cooperative Threat Reduction | $53.0 |

| Operations & Maintenance | <$0.1 |

| Total | $2,029.2 |

| NOTES: Includes funding provided prior to and since passage of the emergency Ebola appropriation. The CDC total includes approximately $50 million in funding provided during the FY 2015 Continuing Resolution (CR) period; this funding could not be disaggregated by international and domestic purposes. Funding for Research & Development (R&D) activities, which totaled $533 million ($364.6 million at HHS and $158 million at DoD) as of September 30, 2015, is not included as this funding could not be disaggregated by international and domestic purposes. SOURCES: Funding obligations as detailed in USAID OIG “Lead Inspector General Quarterly Progress Report on U.S. Government Activities: International Ebola Response and Preparedness, September 30, 2015” and USAID “West Africa – Ebola Outbreak, Fact Sheet #5, Fiscal Year (FY) 2016” released on December 4, 2015. |

|

Of the $1.2 billion that USAID has obligated to the response effort, the majority is provided through the International Disaster Assistance (IDA) account ($870 million), followed by the Global Health Programs (GHP) account ($159 million), and the Economic Support Fund (ESF) account ($125 million). According to USAID, the agency’s emergency funding reimbursed all expenditures incurred prior to passage of the emergency Ebola appropriation.17 As such, the entire funding amount that has been obligated to date by USAID would therefore be attributed to the emergency funding provided by Congress, which would leave approximately $1.3 billion in funding that remains to be obligated.

It is not known whether or not the CDC and DoD emergency Ebola funding was used to reimburse prior activities as was done at USAID. As such, the status of CDC’s $1.2 billion in international funding and DoD’s $112 million in the emergency Ebola funding is not yet known. However, if the CDC’s emergency Ebola funding was used to replace prior obligations, as was done with USAID, then $836 million of the $1.2 billion emergency appropriation would remain for international efforts. DoD has obligated more than $600 million towards its Ebola activities ($474 for the international response and $158 million for research and development activities) using a combination of existing funding, which includes prior appropriations supporting the Overseas Contingency Operations account (OCO), and the $112 million in emergency Ebola funding, of which $17 million was for the international effort and $95 million was for research and development activities.11 It is not known how much of the DoD’s $112 million in emergency Ebola funding has been obligated to date.

Conclusion and Looking Ahead

The Ebola outbreak of 2014 was a global wake-up call regarding the ongoing threat of emerging infectious diseases. After a slow initial response, the U.S. mounted what has become the largest effort by a single donor government to respond to Ebola, including $5.4 billion in emergency funding, the greatest amount of emergency funding ever provided by Congress for an international health emergency. Most of this funding (more than two thirds, or $3.7 billion) was directed toward international activities, both for the initial response as well as ongoing recovery and rebuilding efforts, and is channeled through multiple agencies including USAID, State, CDC and DoD. Agencies report that approximately $2.0 billion has been obligated so far, indicating a significant amount of the emergency Ebola funding remains for ongoing and future activities. Congress made most funding available to agencies for at least a five-year period or available until expended, in recognition of the longer term nature of the challenges ahead and the need to transition to broader support for health systems and public health capacities in the affected countries and beyond.

While we have some general information about how the U.S. has spent and plans to spend the Emergency Ebola funding, many questions remain. At the current time, only limited information is publicly available as to the specific activities funded through the emergency funding. With the exception of USAID, information on the approximately $2.0 billion that has been obligated on the Ebola response thus far is not currently available. Data are also not available to indicate what share of this funding is part of the emergency Ebola appropriation and what is from other funding lines. It is also unclear how much will be directed to longer-term rebuilding and health systems strengthening activities, and exactly what form those activities take. Given that the Ebola response represents a historically large expenditure and is a key humanitarian and health security priority for the U.S. government, understanding how the funds were used and their impact is critical to inform how to respond in future global crises and help to build efforts to address future outbreaks of infectious disease.