While there is currently no standard, agreed-upon definition of global health, the National Academy of Medicine (formerly Institute of Medicine) defines global health as having “the goal of improving health for all people in all nations by promoting wellness and eliminating avoidable diseases, disabilities, and deaths.” A key dimension of global health is an emphasis on addressing inequities in health status between rich and poor countries and also for those who are most marginalized within countries, as well as a recognition that the health of people around the world is highly interconnected, with domestic and foreign health inextricably linked.

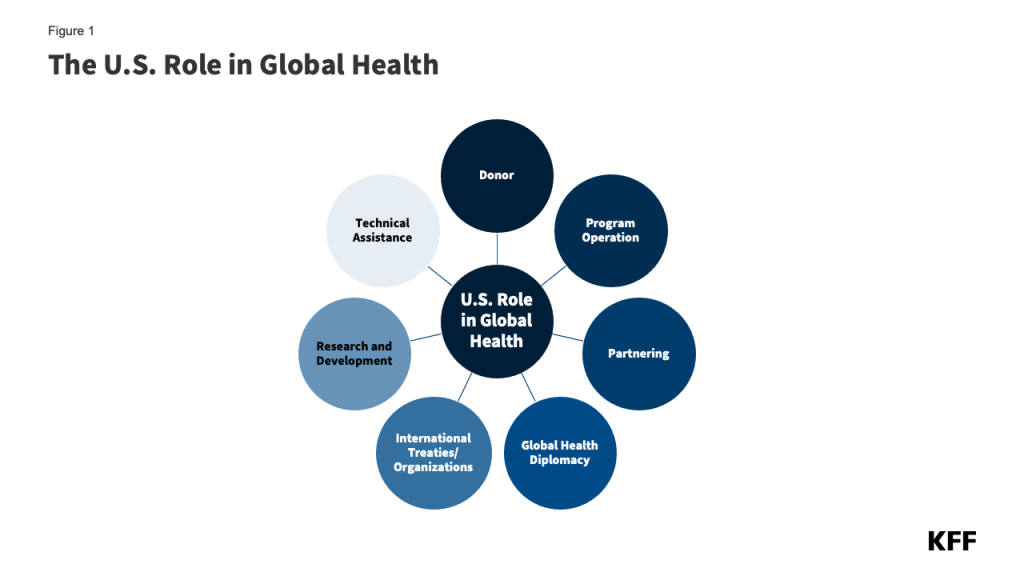

The U.S. government has long been the largest donor to and implementer of global health programs in the world. These efforts have aimed to help improve the health of people in low- and middle-income countries while also contributing to broader U.S. global development goals, foreign policy priorities, and national security concerns, including helping safeguard the health of Americans. These efforts began decades ago and saw major expansion in the early part of the current century with the creation of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and other programs. Since the beginning of the second Trump administration, however, the U.S. global health response has undergone significant change, disruption, and retraction, and the global health landscape has been altered in fundamental ways. This has included, as part of a major review of U.S. foreign aid, the dissolution of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the main implementing agency for U.S. global health programs, the elimination of numerous programs and projects, and the transition of remaining programs to the State Department. As part of its review, the administration is seeking to assess whether U.S. foreign aid programs are aligned with U.S. national interests.

Stephanie Oum

Stephanie Oum  Kellie Moss

Kellie Moss  Jennifer Kates

Jennifer Kates