Children’s Health and Well Being During the Coronavirus Pandemic

Summary

The debate over school openings has highlighted the implications of the coronavirus pandemic for children and their families. While experts continue to gather data on children’s risk for contracting and transmitting coronavirus, current research suggests that though children are more likely to be asymptomatic and less likely to experience severe disease than adults, they are capable of transmitting to both other children and adults. In addition to the risk of disease and illness, COVID-19 has led to changes in schooling, health services delivery, and other disruptions of normal routines that will likely affect children’s health and well-being, regardless of whether they are infected.

This brief examines how a range of economic and societal disruptions stemming from COVID-19 may affect the health and well-being of children and families. It draws on published literature as well as pre-pandemic data from the National Survey of Children’s Health and the National School-Based Health Care Census, recent survey data on experiences during the pandemic, data tracking the number of cases resulting from school openings, and preliminary reports based on claims data evaluating service utilization among Medicaid and CHIP child beneficiaries. It finds that school openings/closures, social distancing, loss of health coverage, and disruptions in medical care could negatively impact the health and well-being children in the US (Figure 1).1 Key findings include:

- Students who attend in person school face direct risks of contracting coronavirus, with early tracking documenting nearly 12,400 cases across 3,900 schools. Risks due to school attendance may be higher for low-income children or children of color, whose families may be less likely to afford alternative schooling arrangements or private transportation to school. A July KFF poll found that parents of color were significantly more likely than White parents to say they were worried about their child contracting coronavirus due to school attendance and that their school lacked adequate resources to safely reopen.

- Students who do not attend school in person also face health risks, including difficulty accessing health care services typically provided through school, social isolation, and limited physical activity. Millions of children access health services through school-based health clinics, school screening and early intervention programs, and on-site counseling, and these services may be suspended in schools that are not open for in person instruction. Children also may be missing opportunities for social connections or exercise, as three-quarters of school-age children take part in a sport, club, or other organized activity or lesson, many of which may be suspended. A quarter of children do not live in a neighborhood with access to sidewalks or walking paths, which could limit physical activity. KFF polls show high rates (67%) of parent concern for their children’s social and emotional health due to school closures.

- Both students attending and not attending in-person school may face emotional or behavioral challenges due to disruptions to routines as well as increases in parent stress and family hardship. Early research has documented high rates of rates of clinginess, distraction, irritability, and fear among children, particularly younger children, as well as increases in some substance use among adolescents, and one survey found that nearly a third of parents said their child had experienced harm to their emotional or mental health. Parent stress due to childcare, schooling, lost income, or other pandemic-related pressures can negatively affect children’s emotional and mental health, harm the parent-child bond and have long-term behavioral implications, and have serious implications for children at risk of abuse or neglect. Exposure to adverse childhood experiences have documented effects of lifelong physical and mental health problems.

- Children are also experiencing consequences of the economic fallout of the pandemic, with at least 20 million children living in a household in which someone lost a job. Though the large majority of children who lose access to employer-sponsored insurance due to job loss are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP, some parents may not enroll children in coverage due to challenges completing the application, lack of knowledge or understanding of eligibility, or other reasons. Many families experiencing loss of income, food insufficiency, or problems paying rent since the pandemic have children, and school closures may make it challenging for the 20 million students who receive free or reduced price lunch to access those meals.

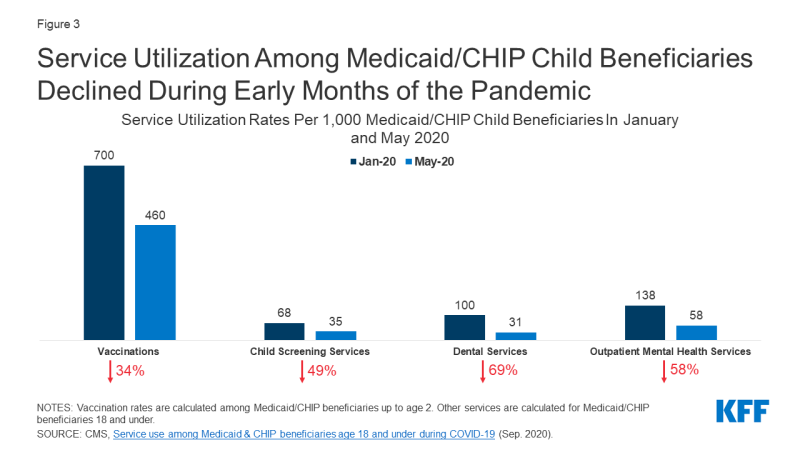

- Parents may be delaying preventative and ongoing care for their children due to social distancing policies as well as concerns about exposure. Reports based on health care claims show declines in rates of vaccinations, child screenings, dental services, and outpatient mental health services among Medicaid/CHIP child beneficiaries (Figure 3). Other administrative data show declines in vaccine orders and administration, particularly among children older than 24 months. It is likely that parents may be delaying care due to concerns about contracting illness or cost concerns, and providers may have limited capacity due to changes in operations to safely treat patients. These delays in care may disproportionately impact the 13 million children with special health care needs who require ongoing care to address their complex needs.

Children’s lower risk of serious illness due to COVID-19 has led most discussion and policy debate over the pandemic to focus on adults at high risk, though the recent debate over school openings has shifted focus to children’s health and well being. Many children are currently facing substantial access barriers, emotional strain, and financial hardship that could have long-term repercussions for their lives. Policies to ensure access to needed health services, particularly behavioral health services, as well as facilitate access to social services to support families with children, can help address some of the consequences children are currently facing.

Introduction

The debate over school openings has highlighted the implications of the coronavirus pandemic for the nation’s 76 million children and their families. Experts continue to gather data on the children’s risk for contracting and transmitting coronavirus, but current research suggests that though children are more likely to be asymptomatic and less likely to experience severe disease than adults, they are capable of transmitting to both children and adults. As of September 17th, 2020, state data indicated that there were over half a million COVID-19 cases among children nationwide, accounting for just over 10% of all cases (children make up about a quarter of the population in the US); however, new cases among children in the period September 3rd through September 17th represented a 15% increase over the prior two week period. In addition, social distancing policies and the economic downturn have important implications for the health and well-being of children, particularly low-income children and children of color. These groups faced increased health, social, and economic challenges prior to the pandemic, and research shows that, like adults, minority and socioeconomically disadvantaged children have a higher risk of contracting coronavirus. This brief provides analysis of the potential implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for children’s mental and physical health, well-being, and access to and use of health care.

Health Risks due to School Openings/Closures and Social Distancing Policies

States and school districts have made varying decisions about how to conduct school in the 2020-21 academic year. As of September 23rd, only Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia had statewide school closures in effect, with five additional states having regional mandatory closures, while four states ordered in-person instruction to be available full or part time. The remaining states have left school operations decisions to localities or are using a hybrid (in-person and on-line) approach to school openings. Most states have given child care facilities, which serve younger children up to Pre-K, the option to open, sometimes with restrictions on class size or other operations.

Students who attend in person school face direct risks of contracting coronavirus, with early tracking documenting nearly 12,400 cases across 3,900 schools. A KFF review found that evidence is mixed about whether children are less likely than adults to become infected when exposed, and while disease severity is significantly less in children, a small subset become quite sick. It further found that though school openings in many other countries have not led to outbreaks among students, the US has much higher rates of community transmission and lower testing and contact tracing capacity and may fare differently. In addition, experience from other countries as well as child care centers in the US shows that school-associated outbreaks do occur, and children do transmit the virus. KFF polling data from July 2020 showed high rates of parent concern over health risks due to school re-opening, with 70% of parents of a child age 5-17 saying they were somewhat or very worried about their child getting sick from coronavirus due to school attendance; parents of color were more likely to express this concern (91% versus 55% of White parents) and also more likely to say their child’s school lacks the resources to safely reopen (82% versus 54% of White parents). As of September 22nd, The National Education Association has confirmed nearly 12,400 cases in Pre-K to high school students across the country. Given the lack of universal testing among students in school and higher likelihood of children being asymptomatic, the number of cases is likely higher than what is reported. Children who contract coronavirus may also pose a risk beyond their school community, as 3.3 million adults age 65 or older live in a household with a school-age child.

The risks of contracting coronavirus due to school may be greater for low-income or minority students due to differences in school structure and commuting patterns. Risks due to schooling and parent decisions about the school year have exposed and exacerbated inequities in the education system. Children in lower-income families are less likely to have access to a “learning pod” that supports in-home instruction and are less likely to have adequate computing resources at home for distance learning and thus may be less likely to opt out of in-person instruction. In addition to higher risk due to in-person attendance, minority or low-income children may be at higher risk from transportation to and from school, as students from low-income households may lack alternatives to school transportation or live in neighborhoods without safe walking routes to school. Data from the 2017 National Household Travel Survey indicates that a higher share of low-income students ride a school bus compared to non-low-income students (60% vs. 45%). Furthermore, Black students travel farther than White and Hispanic students to school. Longer commute times on school busses and other forms of public transportation may put students at higher risk for contracting the virus due to the increased time spent in an enclosed and crowded space.

Students who do not attend school in person may face difficulty accessing health care services typically provided through school. School based health clinics (SBHCs) provide primary care and behavioral health services to nearly 6.3 million students across over 10,600 public schools in the US, accounting for nearly 13% of students nationwide. These clinics are primarily located in schools that serve high concentrations of low-income students and predominantly serve students in grades 6 and above. Additionally, only a small share (just over 10%) of SBHCs are telehealth clinics, with the remainder offering all or most services in person. While some SBHCs may remain open if they serve the broader community, with schools closing, many other SBHCs have likely also shut down, eliminating a source of care for students that rely on them. Outside of SBHCs, schools also provide screening, early intervention, and other health care to their students. In 2016-2018, nearly 1 in 4 students between the ages of 5 and 17 had their vision tested at school (23%), and nearly 10% of children between the ages of 3 and 17 with Autism Spectrum Disorder were first diagnosed by a school psychologist or counselor. About 200,000 students across the US between the ages of 10 and 17 reported using the nurse’s office or athletic trainer’s office as their usual source of care,2 and pre-pandemic, 58% of adolescents who used mental health services received these services in an educational setting, with higher rates among low-income, minority students.

Social distancing policies may result in reduced social connections and physical activity for children. Over three-quarters of older children between the ages of 6 and 17 take part in sports after school or on weekends, are a member of club or organization after school or on weekends, or take part in another form of organized activity or lesson, such as music, dance, language, or other arts.3 Many of these activities are likely cancelled or curtailed due to social distancing policies (even if schools open), leaving many children without social or physical engagement. Parents report high rates of concern about limited social interaction, with data from a July KFF Tracking Poll finding that 67% of parents are worried their children will fall behind socially and emotionally if schools do not reopen. Additionally, as recreational facilities remain closed, opportunities to exercise or spend time outdoors may be limited. Over 1 in 4 families do not live in a neighborhood with sidewalks or walking paths, which could limit children’s ability to spend time outdoors and maintain health.4

Both students attending and not attending in-person school may face emotional or behavioral challenges due to disruptions to routines. There have been widespread reports of the challenges that the disruptions and stress due to pandemic pose to children’s mental health or behavior. Early research reported high rates of clinginess, distraction, irritability, and fear among children, with younger children being more likely to exhibit these behaviors. In a June 2020 survey, 29% of parents reported that their child had already experienced harm to their emotional or mental health. Children with pre-existing mental or behavioral health problems may be at particularly high risk; prior to the pandemic, more than one in ten adolescents ages 12 to 17 had depression or anxiety. Pre-pandemic rates of mental illness were higher among children of color, and these children were also less likely to receive treatment for their mental or emotional problems. Substance use is also a concern, and research has found increases in solitary substance use among adolescents during the pandemic, which is associated with poorer mental health and coping. Behavioral health treatments involve frequent contact with therapists and regular follow-up that may be compromised with limited access to services or school closures during the pandemic. Research has documented long-term effects of adverse childhood experiences, including lifelong physical and mental health problems.

Increases in parent stress may also negatively affect children’s health. With long-term closures of schools and childcare centers, many parents are experiencing new challenges in childcare, homeschooling, and disruption to normal routines. Prior to the pandemic, over half (52%) of all children between the ages of 0-5 received at least 10 hours of care per week from someone other than their parent or guardian, including day care centers, preschools, or Head Start programs.5 During the pandemic, nearly all adults in households with children in school reported a disruption to normal schooling. With many sources of care unavailable, parents who are still working (either in person or via telework) are having to balance childcare or schooling with work. KFF Tracking Polls conducted following widespread shelter-in-place orders found that over half of women and just under half of men with children under the age of 18 have reported negative impacts to their mental health due to worry and stress from the coronavirus.6 Parent stress in coping with the pandemic can negatively affect children’s emotional and mental health, harm the parent-child bond and have long-term behavioral implications, and have serious implications for children at risk of abuse or neglect. A survey conducted in late March 2020 found that a majority of parents (61%) shouted, yelled or screamed at their children at least once in the past 2 weeks and 20% spanked or slapped their child at least once in the past 2 weeks. Social distancing may mean that children have less access to support systems outside members of the household.

Health Risks due to Loss of Family Income

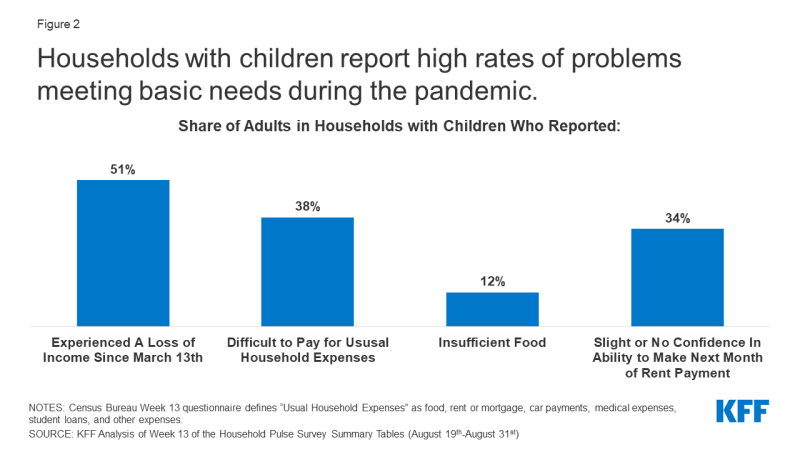

COVID-19 has led to a surge in unemployment and income declines for many families with children. Social distancing policies required to address the crisis have led many businesses to cut hours, cease operations, or close altogether. KFF estimates of job loss between March 1st and May 2nd, 2020 find that over 20 million children are in a family in which someone lost a job. Job losses have continued since that date, and a greater number of children may be in a family in which someone retained their job but has experienced some loss of income. Data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey show that as of August 31st, just over half of adults who have children in the household experienced some loss of employment income since March 13th, 2020, a higher rate than adults without children (42%), and over 30% of adults with children expected a loss of income in the next four weeks (Figure 2).

Job loss may lead to disruptions in children’s health coverage, though most children in families losing employer-sponsored health insurance are likely eligible for coverage under the ACA. KFF analysis of job loss and potential loss of employer coverage as of early May found that millions of people who lost their job as of May 2 were at risk of losing their employer health benefits, and over 6 million people at risk of losing ESI and becoming uninsured are children. The vast majority of these children are eligible for coverage through Medicaid or CHIP, but it is unclear whether they will be enrolled in coverage. Between 2016 and 2018, over one-third of families who had a gap in insurance coverage attributed that gap to unaffordable insurance, health insurance cancellation due to overdue premiums, or a change in employer or employment status. Coverage losses among children will negatively affect their ability to access needed care.7,8,9,10

Loss of family income also affects parents’ ability to provide for children’s basic needs. Data from the August 19-31 Household Pulse Survey shows that 38% of adults in households with children said it was somewhat or very difficult to pay for usual household expenses during the pandemic, a higher share than among adults without children (26%) (Figure 2). The share of households with children who sometimes or often did not have sufficient food to eat increased during the pandemic, with 10% of these households reporting insufficient food prior to March 13th, as compared to 12% as of August 31st. Food insufficiency is particularly pronounced for Black (20%) and Latino (16%) households with children when compared to White (9%) households. Additionally, over one third (34%) of adults in households with children reported only slight or no confidence in their ability to make the next month of rent payment (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Households with children report high rates of problems meeting basic needs during the pandemic.

School closures may further limit low-income children’s ability to access food through free- and reduced-price school meal programs. Just over 1 in 3 students between the ages of 5 and 17 qualifies for a free or reduced cost meal.11 Given that these students often depend on school for two meals a day, school closures may limit their ability to eat regularly and access nutritious food. States and localities are working to continue school meal programs under waivers from the US Department of Agriculture that enable them to provide meals under the Summer Food Service Program or Seamless Summer Option and through new authority to expand the availability of these programs. However, research indicates that only a small share (15%) of the nearly 30 million children who received meals through the program prior to the pandemic continue to do so.

Health Risks due to Disruptions in Health and Social Services

Preliminary reports based on claims data show significant declines in service utilization among Medicaid/CHIP beneficiaries under the age of 18 between January and May 2020, which may be due to social distancing policies as well as concerns about exposure (Figure 3). Prior to the pandemic, utilization of preventive and primary care was generally high among children: In 2018, the large majority (96%) of children had a regular source of health care, nearly 90% had received a well-child visit in the past year, and only a small share (2.5%) delayed care due to cost. However, early analysis of claims data by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) shows substantial declines in use of regular and preventive care. Among Medicaid and CHIP beneficiaries under the age of 2, vaccination rates dropped nearly 34% between January and May 2020. Other services, such as child screening services, dental services, and outpatient mental health services, dropped 50% or more between January and May 2020 for Medicaid and CHIP beneficiaries 18 or younger (Figure 3). Other administrative data across payers show substantial declines in vaccine orders and administration, particularly among children older than 24 months, with cumulative doses of noninfluenza vaccines ordered dropping by more than 3 million by mid-April 2020 compared to the same time in 2019. Parents may be delaying care due to concerns about contracting illness or, for those with private insurance, cost, and providers may have limited capacity due to changes in operations to safely treat patients.

Figure 3: Service Utilization Among Medicaid/CHIP Child Beneficiaries Declined During Early Months of the Pandemic

Though some data shows increases in use of telehealth services among children during the pandemic, it has not offset declines in in-person visits. A July 2020 study found that, prior to the pandemic, only 15% of pediatricians reporting using telemedicine, and many pediatric practices have had to quickly adapt to provide telehealth services during the pandemic. Medicaid, which provides health coverage for nearly 40% of children in the US, is allowing the use of telehealth for Medicaid-funded well-child visits and services, but as of July 23, only 15 states had issued telehealth guidance for child well-care and EPSDT visits and 16 states had issued guidance to providers to allow for telehealth or remote care delivery for early childhood intervention services. Preliminary reports by CMS based on Medicaid claims data shows that delivery of any services via telehealth to children increased by over 2,500% from February to April 2020, but these increases did not offset declines in in-person visits and utilization still declined substantially across many services.

Challenges accessing health services are particularly problematic for the 13 million children with special health care needs (CSHCN). Children with special health care needs require ongoing care and specialized services due to intellectual/developmental disabilities, physical disabilities, and/or mental health disabilities. These disabilities may include asthma, cerebral palsy, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, muscular dystrophy, brain injury, or epilepsy. Many of these children rely on continual care, especially those who have ongoing complications or who have recently had procedures. However, due to social distancing rules and risk of exposure in health care settings, CSHCN may forgo necessary care. Additionally, CSHCN and their families rely on home-based medical caregiving to supplement other sources of care. These include children with particularly complex care needs who may rely on nursing care to live safely at home with a tracheotomy or feeding tube. However, given staffing shortages and other complications brought on by the pandemic, home nursing and aide services may no longer be an option for many families.

The pandemic has led to many services in child welfare systems being cut back or postponed, leading to concerns of both increased child abuse and decreased reporting. Many child welfare agencies have cut back on in-person inspections of homes, which puts vulnerable children at even greater risk for abuse and neglect. Child welfare professionals also report concern that the pandemic will fuel a rise in child abuse and neglect, given the increasing stress on families and working parents. There are also concerns of decreased reporting of child abuse and neglect that may stem from social distancing policies. States including Wisconsin, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Illinois saw reports of child abuse fall between 20% and 70% in the month of March, likely due to children being kept away from locations where there are professionals who are trained to identity and report scenarios of child abuse and neglect. The pandemic may also lead to an increased need for child welfare services, as increased financial pressures on families negatively impact parents’ relationships with their children. This additional need could remain unmet as the child welfare system struggles to handle its current caseload and families in need with the additional complications presented by COVID-19.

Looking Ahead

The coronavirus pandemic is an unprecedented event in most people’s lifetimes, leading to extraordinary high risk to health and well-being. Children’s lower risk of serious illness due to COVID-19 has led most discussion and policy debate over the pandemic to focus on adults at high risk, though the recent debate over school openings has shifted focus to children’s health and well-being. With many schools re-opening, tracking cases and serious illness among children and understanding who is at highest risk can help policymakers design education and support systems to minimize exposure, risk, and illness. In addition, many children are already facing substantial access barriers, emotional strain, and financial hardship that could have long-term repercussions for their lives. This analysis underscores the importance of pursuing safe approaches to opening schools to balance physical and emotional health. Policies to facilitate enrollment in health coverage, ensure access to health services, particularly behavioral health services, as well as facilitate access to social services to support families with children, can help address some of the consequences children are currently facing.