THE UNINSURED A PRIMER 2013 – 5: WHAT ARE THE FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS OF LACK OF COVERAGE?

For many uninsured people, the costs of health insurance and medical care are weighed against equally essential needs. When people without health coverage do receive health care, they may be charged for the full cost of that care, which can strain family finances and lead to medical debt. Uninsured people are more likely to report problems with high medical bills than those with insurance. Low-income individuals, who comprise a large share of the uninsured population, were three times as likely as those with higher incomes to report having difficulty paying basic monthly expenses such as rent, food, and utilities.1

Most uninsured people do not receive health services for free or at reduced charge. Hospitals frequently charge uninsured patients two to four times what health insurers and public programs actually pay for hospital services.2 More than half of uninsured adults paid full price for their usual source of care, with 82% of uninsured adults who used any medical services in the previous year paying some amount out-of-pocket for health care.3

Uninsured people often must pay “up front” before services will be rendered. When people without health coverage are unable to pay the full medical bill in cash at the time of service, they can sometimes negotiate a payment schedule with a provider, pay with credit cards (typically with high interest rates), or can be turned away.4

People without health coverage spend less than half of what those with coverage spend on health care, but they pay for a much larger portion of their care out-of-pocket. In 2008, the average person who was uninsured for a full-year incurred $1,686 in total health care costs compared to $4,463 for the nonelderly with coverage.5 However, these averages are affected by the high number of uninsured individuals that do not seek health care at all.6 The uninsured pay for about a third of this care out-of-pocket, totaling $30 billion in 2008. This total included the health care costs for those uninsured all year and the costs incurred during the months the part-year uninsured have no health coverage.

The remaining costs of their care, the uncompensated costs for the uninsured, amounted to about $57 billion in 2008. About 75% of this total ($42.9 billion) was paid by federal, state, and local funds appropriated for care of the uninsured population.7 Nearly half of all funds for uncompensated care come from the federal government, with the majority of federal dollars flowing through Medicare and Medicaid. While substantial, these government dollars amount to a small slice (2%) of total health care spending in the U.S.

The burden of uncompensated care varies across providers. Hospitals incur 60% of the cost of uncompensated care because of the high cost of medical needs requiring hospitalization, despite the fact that physicians and community clinics see more uninsured patients.8 Most government funding of uncompensated care is paid to hospitals based indirectly on the share of uncompensated care they provide. The cost of uncompensated care provided by physicians is not directly or indirectly reimbursed by public dollars.

Safety net hospitals that serve a large number of uninsured individuals will receive a reduction in federal disproportionate share (DSH) payments beginning in 2014. DSH payments are federal Medicaid payments intended to cover the extra cost experienced by hospitals serving a large number of low-income and uninsured patients. Unlike other Medicaid payments, federal DSH funds are capped at a state’s annual allotted amount, determined by statutory formula, and states have two years to claim their allotments. DSH allotments currently vary considerably across states and total about $11 billion a year.9 In 2014, when many states will expand Medicaid eligibility to 138% of poverty, the ACA will begin reducing DSH payments, with total reductions by 2022 estimated to be more than $22 billion.10 However, some states may elect not to expand Medicaid eligibility, which would leave uninsured residents with few low-cost coverage options and the hospitals that serve these individuals with less federal DSH funding.

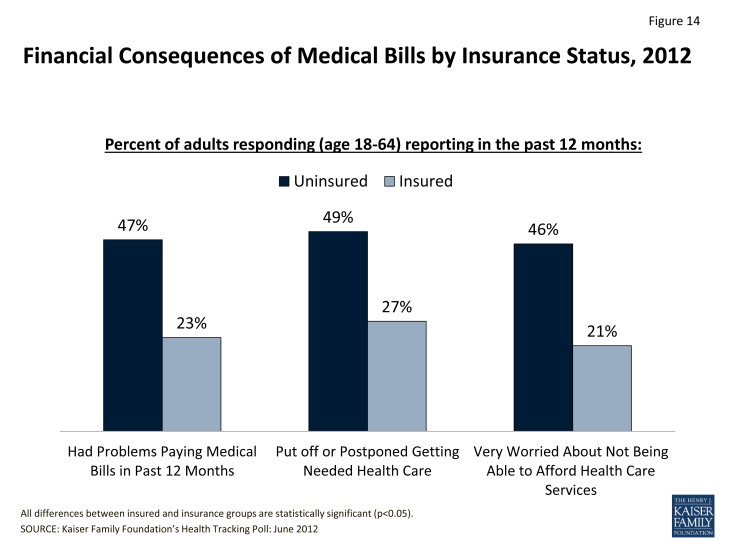

Being uninsured leaves individuals at an increased risk of amassing unaffordable medical bills. Uninsured people are almost twice as likely (47% versus 23%) as those with health insurance coverage to report having trouble paying medical bills (Figure 14). Medical bills may also force uninsured adults to exhaust their savings. In 2010, 27% of uninsured adults used up all or most of their savings paying medical bills, as compared with 7% of those with coverage.11

Most of uninsured people have few, if any, savings and assets they can easily use to pay health care costs. Half of uninsured families living below 200% of poverty have no savings at all,12 and the average uninsured household has no net assets.13 Uninsured people also have far fewer financial assets than those with insurance coverage. A recent survey found that almost half (46%) of uninsured people are not confident that they can pay for the health care services they think they need, compared to 21% of people with insurance (Figure 14).

Unprotected from medical costs and with few assets, uninsured people are at risk of being unable to pay off medical debt. Like any bill, when medical bills are not paid or paid off too slowly, they are turned over to a collection agency, and a person’s ability to get further credit is significantly limited. Almost one-quarter (23%) of uninsured nonelderly individuals have medical bills that they are unable to pay at all, compared to 6% of those with private insurance.14 Medical debts contribute to almost half of the bankruptcies in the United States, and uninsured people are more at risk of falling into medical bankruptcy than people with insurance.15

Endnotes

Collins et al. 2011

Anderson G. 2007. “From ‘Soak The Rich’ To ‘Soak The Poor’: Recent Trends In Hospital Pricing.” Health Affairs 26(4): 780-789.

Carrier E, Yee T, and Garfield R. 2011.

Asplin B, et al. 2005. “Insurance Status and Access to Urgent Ambulatory Care Follow-up Appointments.” JAMA 294(10):1248-54.

Hadley J, Holahan J, Coughlin T, and Miller D. 2008. “Covering the Uninsured in 2008: Current Costs, Sources of Payment, and Incremental Costs.” Health Affairs 27(5):w399-415.

Caswell K, O’Hara B. 2010. “Medical Out-of-Pocket Expenses, Poverty, and the Uninsured.” U.S. Census Bureau. Available at: http://www.census.gov/hhes/povmeas/methodology/supplemental/research/Caswell-OHara-SGE2011.pdf

Hadley J, et al. 2008.

Hadley J, et al. 2008.

“Federal Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Allotments,” Kaiser Family Foundation. http://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/federal-dsh-allotments/

Congressional Budget Office. July 2012. “Estimates for Insurance Coverage Provisions of the Affordable Care Act Updated for the Recent Supreme Court Decisions.” Available at:

http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/43472-07-24-2012-CoverageEstimates.pdf

Kaiser Family Foundation’s Health Tracking Poll: June 2010. Available at: http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/8082.cfm

Glied S and Kronick R, 2011. “The Value of Health Insurance: Few of the Uninsured Have Adequate Resources to Pay Potential Hospital Bills.” Office of Assistance Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/2011/ValueofInsurance/rb.pdf

Jacobs P and Claxton G. 2008. "Comparing the Assets of Uninsured Households to Cost Sharing Under High Deductible Health Plans," Health Affairs 27(3):w214

Cohen RA, et al. 2012. “Financial Burden of Medical Care: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January-June 2011.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/financial_burden_of_medical_care_032012.pdf

Himmelstein D, et al. 2009. “Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: results of a national study.” Am J Med. 122(8): 741-6. Available at: http://www.pnhp.org/new_bankruptcy_study/Bankruptcy-2009.pdf