Medicaid in an Era of Health & Delivery System Reform: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2014 and 2015

Vernon K. Smith, Kathleen Gifford, Eileen Ellis, Robin Rudowitz, and Laura Snyder

Published:

Executive Summary

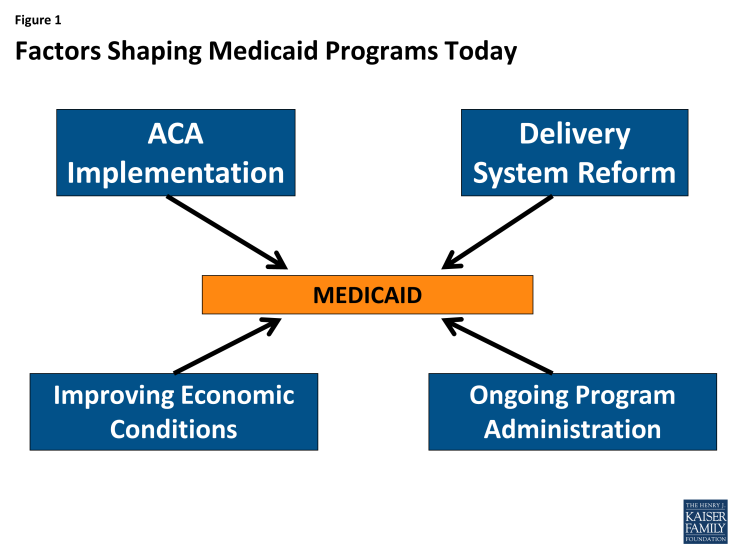

Medicaid has long-played an important role in the US healthcare system, accounting for one in every six dollars of all US health care spending while providing health and long-term services and supports coverage to over 66 million low-income Americans. However, the years 2014 and 2015 will stand out as a time of significant change and transformation. With the economy improving from the lingering effects of the Great Recession, Medicaid programs across the country were focused primarily on: implementing a myriad of changes included in the Affordable Care Act (ACA); pursuing innovative delivery and payment system reforms to help assure access, improve quality and achieve budget certainty, and continuing to administer this increasingly complex program. (Figure 1)This report provides an in depth examination of the changes taking place in state Medicaid programs across the country. The findings in this report are drawn from the 14th annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and Health Management Associates (HMA), with the support of the National Association of Medicaid Directors. This report highlights policy changes implemented in state Medicaid programs in FY 2014 and those planned for implementation in FY 2015 based on information provided by the nation’s state Medicaid Directors.

Key areas covered include changes in eligibility and enrollment, delivery systems, provider payments and taxes, benefits, pharmacy programs, program integrity and program administration.

In FY 2014 and FY 2015, states were implementing a host of ACA-related eligibility and enrollment changes in Medicaid.

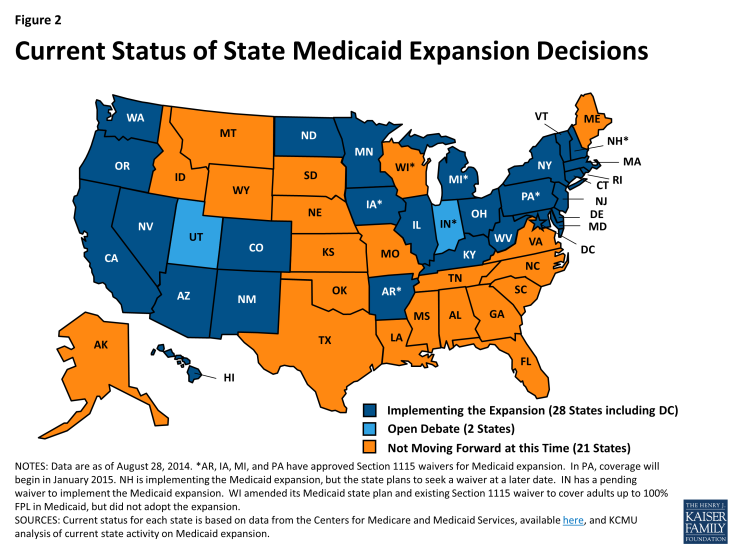

Many of the Affordable Care Act’s provisions affecting Medicaid eligibility and enrollment went into effect during FY 2014, most significantly the Medicaid expansion. Medicaid’s role, as enacted under the ACA, was broadened to become the foundation of coverage for nearly all low-income Americans with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL); however, the Supreme Court ruling on the ACA effectively made the decision to implement the Medicaid expansion an option for states. As of September 2014, 28 states (including DC) are implementing the Medicaid expansion. Regardless of the expansion decision, all states were required to streamline Medicaid enrollment and renewal processes, transition to a uniform income eligibility standard (Modified Adjusted Gross Income or MAGI) and coordinate with new Marketplaces.

In addition to changes required by the ACA in all states to streamline Medicaid eligibility and enrollment processes,31 states made eligibility expansions in FY 2014, the most common being implementation of the Medicaid expansion. Twenty-six states implemented the Medicaid expansion in FY 2014. New Hampshire implemented the Medicaid expansion in July 2014 (FY 2015) and Pennsylvania received approval in August 2014 to implement the expansion in January 2015, bringing the total number of states moving forward with the Medicaid expansion to 28 states as of September 2014. Medicaid expansion is under consideration in additional states, notably Indiana which has submitted a request to expand Medicaid under a waiver and Utah which has a request under development. Other states reported that there will be discussion of Medicaid expansion in their next legislative session. (Figure 2)

States reported a number of changes to better align new and pre-ACA coverage options. For example, some states that had previously expanded Medicaid coverage to adults with incomes above poverty are eliminating such coverage in light of new coverage options available through the Marketplaces. Four states reported Medicaid eligibility restrictions. Meanwhile, children’s coverage remains strong as maintenance of eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP children is in place through 2019.

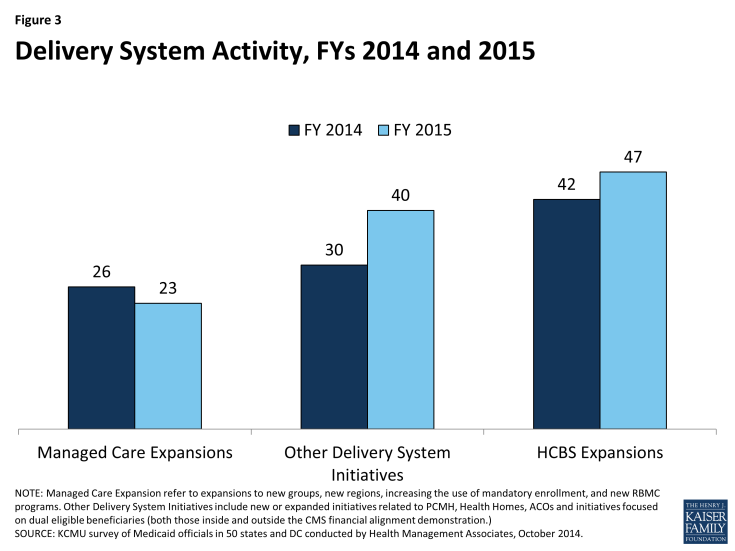

Focus on delivery system reforms in Medicaid programs continued to build in FY 2014 and FY 2015. (Figure 3)

Most Medicaid programs use managed care as a means to help assure access, improve quality and achieve budget certainty. As of July 2014, all states except three – Alaska, Connecticut and Wyoming – had in place some form of managed care including risk-based comprehensive managed care organizations (MCO), Primary Care Case Management (PCCM) programs or both. States continued to take actions to increase enrollment in managed care. Of the 39 states (including DC) with MCOs, over half in FY 2014 and FY 2015 reported specific policy changes to increase the number of enrollees in risk-based managed care by adding eligibility groups, making enrollment mandatory or expanding to new regions. In addition to expanding managed care, new quality improvement initiatives such as adding or enhancing pay-for-performance arrangements to their managed care contracts were implemented in 34 states in FYs 2014 or 2015.

Aside from managed care changes, well over half of states reported other delivery system reform initiatives underway (30 states in FY 2014 and 40 states in FY 2015.) Just over half the states (26) planned to implement or expand Medicaid health homes in FY 2015, up from 14 in FY 2014. Nearly half of states had patient centered medical homes in place in FY 2013; an additional 17 states in FY 2014 and 20 in FY 2015 were implementing or expanding such initiatives. Over a third of states (19) plan to implement initiatives focused on coordinating care for those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid in FY 2015, up from 10 states in FY 2014 and 5 states in FY 2013. A smaller number of states reported delivery system and payment reforms related to Accountable Care Organizations (ACO), episode of care initiatives, and hospital Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) programs.

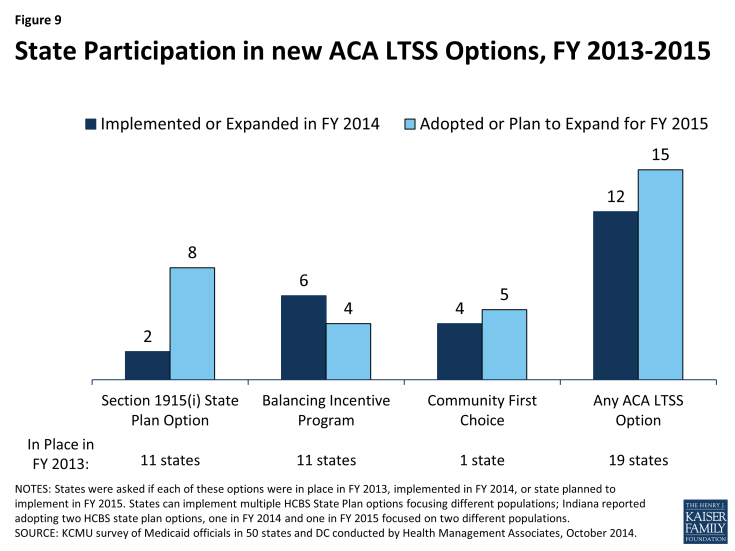

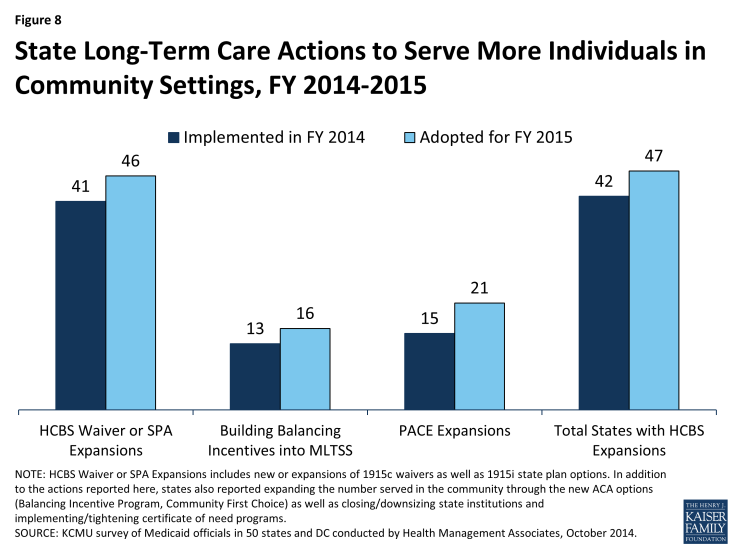

In FY 2014 and FY 2015, 42 and 47 states, respectively, took actions that expanded the number of persons served in a home and community-based services (HCBS) setting, notably higher than the number of states taking such action in FY 2012 (26) and FY 2013 (33). While most states reported using Section 1915(c) waiver authority to expand HCBS, a significant number of states (13 in FY 2014 and 16 in FY 2015) reported that the incentives built into their managed long-term services and support (LTSS) programs were expected to increase the number of people served in community settings. Nineteen states had at least one of the new ACA long-term services and supports options in place in FY 2013; an additional 12 states in FY 2014 and 15 states in FY 2014 plan to implement one or more of these options.

States also reported activity in other areas including provider rates and taxes, premiums and cost sharing, prescription drugs, and program integrity.

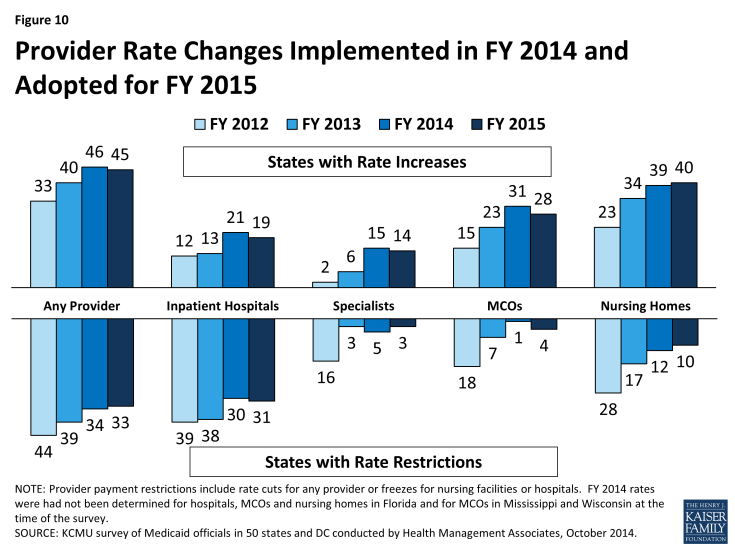

Provider Rates. As economic conditions have continued to improve, states have been able to implement program restorations or increases in provider rates. More states implemented provider rate increases across most major provider types (physicians, nursing homes and managed care) in FY 2014 and FY 2015, inpatient hospital rates being the exception. This survey also asked states about plans to extend the primary care physician fee increase beyond December 31, 2014 (at regular FMAP rates); 24 states indicated that they would not be continuing the rate increase while 15 states indicated that they will continue the higher rates at least partially. Some had not decided at the time of the survey. Other states have Medicaid physician rates that are already close to 100 percent of Medicare rates, making the issue less significant in these states.

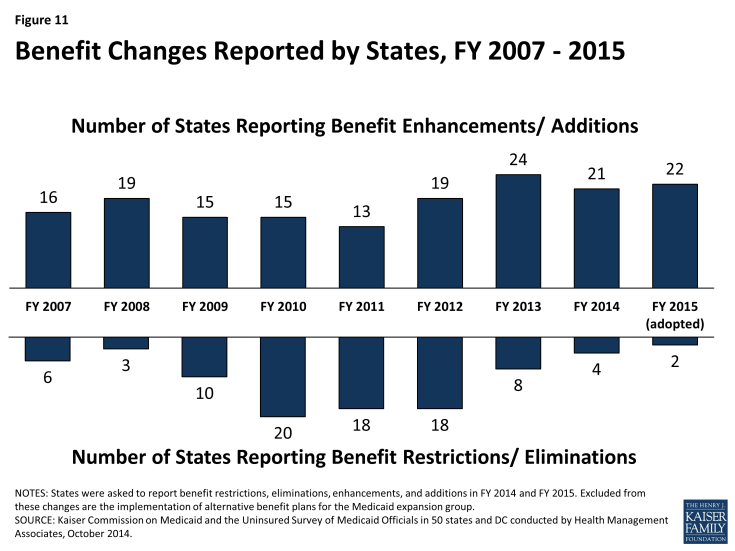

Benefits. The number of states reporting benefit cuts or restrictions – four in FY 2014 and two in FY 2015 – fell to the lowest level since 2008. A far larger number (21 states in FY 2014 and 22 in FY 2015), reported expanding benefits, most commonly behavioral health, dental and home and community-based services.

Pharmacy. A little over half of the states continue to take steps to refine their pharmacy programs, and almost all states are concerned about the potential future fiscal impact of new and emerging specialty drug therapies. Many states (22) reported that new clinical prior authorization criteria were already in place or under development to help address such concerns.

Cost-Sharing. There was a modest increase in the number states reporting actual or planned cost-sharing increases compared to earlier years. About half of these increases were for higher income expansion groups.

Program Integrity. States continue to implement new or enhanced program integrity initiatives including the use of advanced data analytics and predictive modeling, efforts focused on managed care, enhanced provider screening, and public/private data sharing initiatives.

Looking ahead, states plan to focus on implementing the ACA, putting into place innovative delivery system reforms and continuing to manage a complex program with limited staff and resources.

In the history of Medicaid, the years 2014 and 2015 will stand out as a time of significant change. For most states, implementation of the Medicaid changes under the ACA was transformative for Medicaid from policy, operations and systems perspectives. At the same time, Medicaid programs across states have continued to increase their focus on delivery system and payment reform with the goals of improving quality of care and controlling costs. States are expanding their reliance on managed care but also implementing new innovative delivery system and care coordination arrangements, some of which are new options made available by the ACA. In coordination with these efforts, Medicaid programs are also focused on better ways to deliver long-term care services and supports by expanding home and community-based service programs. More states have been able to implement provider rate increases as well as benefit increases as the economy has continued to slowly recovery. Most Directors reported staffing and resource constraints in the face of the magnitude of changes occurring in the program today. Despite these challenges, Medicaid continues to evolve to meet the needs of the growing number of people it serves and to play a larger role in the broader health care delivery system.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Medicaid directors and Medicaid staff in all 50 states and the District of Columbia who completed the survey on which this study is based. Especially in this time of limited resources and challenging workloads, we truly appreciate the time and effort provided by these public servants to complete the survey, to participate in structured interviews and to respond to our follow-up questions. It is their work that made this report possible.

We offer special thanks to two of our colleagues at Health Management Associates. Dennis Roberts developed and managed the database, and his work is invaluable to us. Jenna Walls assisted with writing the case studies and we thank her for her excellent work.

Report

Introduction

This report provides an in depth examination of the changes taking place in state Medicaid programs across the country. The findings in this report are drawn from the 14th annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and Health Management Associates (HMA), with the support of the National Association of Medicaid Directors. This was the fourteenth annual survey, conducted at the beginning of each state fiscal year from FY 2002 through FY 2015.

The KCMU/HMA Medicaid survey on which this report is based was conducted from June through August 2014. Medicaid directors and staff provided data for this report in response to a written survey and a follow-up telephone interview. All 50 states and DC completed surveys and participated in telephone interview discussions between June and August 2014. The survey asked state officials to describe policy changes that occurred in FY 2014 and those adopted for implementation for FY 2015 (which began for most states on July 1, 2014.1) The survey does not attempt to catalog all Medicaid policies. Experience has shown that adopted policies are sometimes delayed or not implemented, for reasons related to legal, fiscal, administrative, systems or political considerations, or due to delays in approval from CMS. Policy changes under consideration are not included in the survey. A copy of the survey instrument is located in the appendix of this report.

Key findings of this survey, along with 50-state tables providing more detailed information, are described in the following sections of this report:

- Eligibility and Enrollment

- Delivery System Reforms

- Managed Care

- Other Delivery System Reforms

- Balancing Institutional and Community-Based Long-Term Services and Supports

- Provider Rates and Taxes or Fees

- Benefits Changes

- Premiums and Cost-Sharing

- Prescription Drug Utilization and Cost Control Initiatives

- Program Integrity Initiatives

- Medicaid Administration and Priorities

Eligibility and Enrollment

The ACA included a number of significant changes for Medicaid eligibility and enrollment. One of the most significant changes extends Medicaid coverage to nearly all non-elderly low-income adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($16,104 per year for an individual in 2014), ending the Medicaid eligibility exclusion for adults without dependent children or childless adults regardless of their income. However, the June 2012 Supreme Court ruling on the ACA effectively made the decision to implement the Medicaid expansion optional for states. The ACA also required states to transition to the use of Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) to determine Medicaid financial eligibility for children, pregnant women, parents and low income adults; eliminate asset limits for these same groups; transition children with income between 100 and 133 percent FPL from the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) to Medicaid; and to use new streamlined application, enrollment, and renewal processes. In addition, Medicaid agencies were required to coordinate enrollment processes with the new Marketplaces. Altogether, the eligibility changes in 2014 represent historic program changes.

Eligibility Standards

A total of 31 states reported at least one eligibility expansion in FY 2014 and eight states reported planned eligibility expansions in FY 2015; the ACA Medicaid expansion was the most commonly reported change. In contrast, four states made eligibility restrictions in FY 2014; no states reported restrictions in FY 2015. However, many states (24 in FY 2014, 6 in FY 2015) made changes to existing Medicaid eligibility pathways due to the availability of new coverage through the Marketplace; these changes are not counted as restrictions or expansions in this report.

Adult Coverage Changes Under the ACA

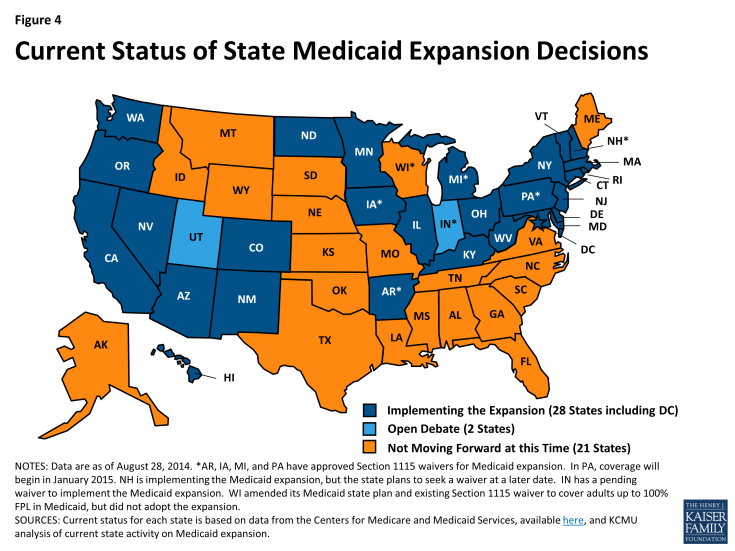

In FY 2014, 26 states including the District of Columbia expanded Medicaid for low-income adults, either under the direct provisions of the ACA or through waivers (Arkansas, Iowa, and Michigan). For FY 2015, New Hampshire implemented the Medicaid expansion in July 2014, and Pennsylvania received CMS approval of the Healthy Pennsylvania waiver that will expand Medicaid eligibility for low-income adults as of January 1, 2015. As of September 2014, the total number of states implementing the Medicaid expansion is 28 (including DC.) (Figure 4) Two states (Indiana and Utah) continue discussions about implementing the Medicaid expansion. Indiana has submitted a formal waiver application that is under review at CMS; elements of this waiver proposal are discussed throughout the report in relevant sections. Utah’s Governor continues to negotiate with CMS but has not yet made a formal submission. Medicaid officials in several states noted that expanding Medicaid to more low-income adults would be discussed in the next legislative session.

With more coverage options available across the income spectrum, some states made changes to existing Medicaid eligibility pathways to better conform to those options. These changes are included in Tables 1 and 2, but are not regarded as restrictions unless individuals previously covered through these pathways would not be expected to have access to coverage through these new options. States making these changes largely fall into three groups: 1) Medicaid expansion states changing Medicaid waiver coverage over 138 percent FPL; 2) States that have not adopted the expansion reducing Medicaid coverage over 100 percent FPL; and 3) States reducing or eliminating certain optional eligibility groups.

Medicaid expansion states changing Medicaid waiver coverage over 138 percent FPL

A few states had expanded eligibility to adults above 138 percent FPL prior to the ACA under waiver authority. With the availability of new coverage options in the Marketplace, seven states (California, Iowa, Massachusetts, New Mexico, New York, Rhode Island and Vermont) eliminated Medicaid coverage in their waivers for adults with incomes over 138 percent FPL. Three of these states (Massachusetts, New York and Vermont) have received or are seeking approval under a Medicaid waiver to use Medicaid funds to provide premium assistance that further subsidizes Marketplace coverage for individuals previously covered under their waiver.

In contrast, three states (Connecticut, DC and Minnesota) maintained coverage of adults with incomes over 138 percent FPL at the state’s regular match (FMAP.) Connecticut is maintaining its eligibility level for parents at 201 percent FPL.1 The District of Columbia is shifting its waiver for adults with income between 138 and 200 percent FPL to its state plan. Minnesota, which previously covered adults up to 275 percent FPL in MinnesotaCare, is maintaining waiver coverage for those up to 200 percent FPL and plans to shift this group to the new Basic Health Plan option in 2015.

| Basic Health Plan |

| At least two states, New York and Minnesota, plan to implement a Basic Health Plan (BHP.) Under the BHP provisions of the ACA, a state receives 95 percent of what the federal government would have spent on premium and cost-sharing subsidies in the Marketplace for the eligible population. The state then provides coverage through a state-managed BHP. While the BHP is not part of Medicaid, it could affect Medicaid in these states. For example, Minnesota currently provides Medicaid to adults with incomes between 138 and 200 percent FPL who would likely be eligible for Marketplace subsidies; the state plans to move these adults to a BHP in 2015. New York plans to implement a BHP starting with immigrants under 200 percent FPL that currently receive coverage funded solely by the state; the BHP would then expand to another 200,000 adults between 138 and 200 percent FPL. |

States that have not adopted the expansion reducing Medicaid coverage over 100 percent FPL

A few states that have not adopted the Medicaid expansion covered adults above 100 percent FPL before the ACA was enacted, largely through waivers. Some of these states made eligibility changes in response to the availability of new Marketplace coverage options in 2014. In states not adopting the Medicaid expansion in 2014, those with incomes above 100 percent FPL in most cases will be eligible for subsidies to purchase coverage in the Marketplace.

- Indiana2 and Oklahoma reduced existing adult eligibility from 200 to 100 percent FPL in waiver renewals.

- Wisconsin reduced eligibility levels for its existing waiver for adults from 200 to 100 percent FPL and expanded coverage to childless adults by eliminating the waiting list for coverage under its existing waiver.

- Maine reduced state plan coverage for parents and caretakers from 133 to 105 percent FPL.

States reducing or eliminating certain optional eligibility groups

The availability of subsidized Marketplace coverage and expanded Medicaid coverage (in 28 states) provides new options for states to reconsider coverage policies for certain optional, limited benefit eligibility groups, such as the family planning group, some spend-down programs, and the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment (BCCT) program.3 While most states reported no current plans to change these eligibility pathways; a few states did report eliminations or reductions:

- Nine states reported ending family-planning only coverage (Arizona, Arkansas, Delaware, Michigan, and Oklahoma in FY 2014; Illinois, Louisiana4, New Mexico and Pennsylvania in FY 2015.) Virginia also reduced eligibility for this group to 100 percent FPL in 2014 but plans to restore coverage to 200 percent FPL in 2015.

- Five states (Hawaii, Illinois, and North Dakota in FY 2014 and Kentucky and Pennsylvania in FY 2015) reduced or eliminated eligibility for their medically needy programs for non-elderly non-disabled adults. In contrast, Minnesota increased the medically needy income limit for parents, children, and pregnant women.

- Three states (Arkansas, Maryland in FY 2014; Kentucky in FY 2015) ended or plan to end the BCCT program.

Other Eligibility Changes for Adults

Two states made additional changes to Medicaid eligibility levels for adults aside from the changes made in response to the ACA. Montana increased the cap on enrollment in its Mental Health Services Plan (MHSP) waiver from 800 individuals to 2,000 individuals in FY 2014 and to 6,000 in FY 2015. Maine allowed its existing waiver that covered childless adults up to 100 percent FPL to expire, leaving most of the 9,000 individuals affected by this change without a coverage option, since eligibility for subsidies through the Marketplaces is limited to individuals with incomes above 100 percent FPL.

Eligibility Changes for Elderly Individuals and Those with Disabilities

Few states reported eligibility expansions or restrictions for this group. Two states (Florida in FY 2014 and New Jersey in FY 2015) reported expanding eligibility by increasing income and asset limits while two states (Arkansas and Louisiana) reported reducing or eliminating buy-in programs that allow working individuals with disabilities with higher amounts of income and assets than other elderly or disabled individuals to obtain Medicaid coverage. Two additional states reported more complex changes:

- Indiana’s spend-down program was eliminated as a result of changing its methods for determining disability for Medicaid coverage.5 The spend-down program allowed those that otherwise qualified except for their income/assets to qualify after taking into account their medical expenses. Some of the 31,500 individuals affected by this decision obtained coverage in the Marketplace but some lost coverage. Some of the 31,500 that lost coverage also got assistance from the Medicare Savings Program (which provides Medicaid assistance with Medicare premiums and cost-sharing); the state increased the income limit for this program. Indiana also implemented a 1915(i) HCBS state plan amendment that will result in full Medicaid coverage for those with income up to 300 percent FPL and severe mental health conditions which will also cover some of those that lost spend-down coverage.

- Louisiana eliminated optional coverage for aged and disabled individuals with incomes up to 100 percent FPL. Those that qualify for Supplemental Security Income (SSI, about 74 percent FPL) remain eligible for Medicaid, but approximately 8,000 Medicaid cases were closed as a result of the decision. The state also added an optional coverage group which will provide interim Medicaid-only benefits for those awaiting an SSI determination. Separately, the state implemented spend-down eligibility for four HCBS waivers.

Eligibility Changes for Pregnant Women and Children

Two states (Oklahoma and Louisiana) reduced eligibility for pregnant women to 138 percent FPL in FY 2014. Pregnant women losing eligibility in both states are likely eligible for coverage either through the Marketplace or CHIP in Louisiana. (As such, neither of these changes is counted here as a restriction.) Additionally, California and Rhode Island are working on initiatives to assist pregnant women with incomes above 138 percent FPL to purchase Marketplace coverage using Medicaid funding.

For children, the ACA implemented new policies across all states to help strengthen children’s coverage, such as providing Medicaid coverage to children aging out of foster care up to age 26 and requiring states to maintain eligibility thresholds for children that are at least equal to those in place at the time the ACA was enacted through September 30, 2019. In addition, the law established a minimum Medicaid eligibility level of 138 percent FPL for all children up to age 19. Prior to the ACA, the federal minimum eligibility levels for children varied by age, and the federal minimum for older children ages 6 to 18 was 100 percent FPL. As a result of the law, 21 states needed to transition children from CHIP to Medicaid in 2014; states still receive the enhanced CHIP federal matching rate for coverage of these children. (This change was not included in this report as an eligibility change since coverage for these children continues to be financed with Title XXI funds.)

See Tables 1 and 2 for more information on eligibility changes in FY 2014 and FY 2015.

Enrollment Procedures

In addition to changes in eligibility standards, some states were adopting options to further streamline application and renewal processes beyond those required by the ACA. States were also asked to report on implementation of hospital presumptive eligibility, efforts to coordinate with the Marketplaces, status of application backlogs, and plans for the next open enrollment period for Marketplace coverage.

Streamlining Options

Beyond changes required by the ACA, CMS offered states (in a letter dated May 17, 2013) the opportunity for expedited waivers for several new options that would further streamline application and renewal processes and facilitate enrollment. A majority of states implemented one of these options, namely to delay the annual Medicaid eligibility redeterminations that would normally have occurred during the first quarter of calendar 2014. For individuals scheduled for eligibility redetermination during this period, this waiver allowed Medicaid coverage to continue while staff were adjusting to the new MAGI income counting rules in all states and were focused on implementing the ACA Medicaid expansion in about half of states. Several states asked for and received extensions beyond March 31st that further delayed renewals for Medicaid enrollees. Also, as reported last year, about one third of states adopted an option to implement the MAGI rules before January 1, 2014. As of August 2014, CMS had approved the following states to use the remaining streamlining options:

- Seven states (Arkansas, California, Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey, Oregon, and West Virginia) were approved to facilitate enrollment into Medicaid through administrative data transfer using Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) data.

- Four states (California, New Jersey, Oregon, and West Virginia) were approved to enroll parents based on income data available from their children’s eligibility application.

- No state had an approved waiver to adopt 12 month continuous eligibility for adults under this option.

States were asked about their plans to adopt these options in FY 2015. Washington reported plans to adopt the administrative data transfer option, and Kansas planned to implement 12 month continuous eligibility for adults. Several states noted that they have adopted strategies (e.g. express lane eligibility) that use SNAP data to facilitate Medicaid enrollment or target outreach. New York also reported having adopted 12 month continuous eligibility for adults, but under their existing 1115 waiver.6

Hospital Presumptive Eligibility (HPE)

Starting in January 2014, the ACA allows qualified hospitals to make Medicaid presumptive eligibility determinations in accordance with an approved State Plan Amendment. CMS issued HPE rules governing the state implementation of HPE on January 24, 2014, which delayed adoption in many states.7 Only 11 states reported implementing HPE in January (with later CMS approval). At the time of the survey, an additional 18 states had implemented HPE and three other states with approved plans expected to implement in the fall. Another 17 states reported that they had submitted state plan amendments to CMS but had not yet received approval; these states were in various stages of discussions with CMS and were also developing training materials. Four states indicated that their HPE plans were still under development. States reported a great deal of variation in hospital participation levels and in the volume of applications received through HPE. Among states that implemented HPE early, hospital participation ranged from only a few in some states to the majority of Medicaid hospitals. Some states indicated that hospitals were not interested in participating because it was easy to enroll individuals in Medicaid using “real time” on-line eligibility systems.

| Other Key Enrollment Issues Related to the Marketplace |

|

Marketplace Interface. Almost all states experienced challenges in establishing a smooth interface between Medicaid and the Marketplace, whether the Marketplace was a Federally Facilitated Marketplace (FFM), State-Based Marketplace (SBM), or a Federal Partnership Marketplace (FPM). This interface required an unprecedented level of cooperation across agencies (within state government, and/or between states and federal agencies) and across IT systems. Medicaid programs with fully operational SBMs reported the fewest interface issues. In at least six states (Kentucky, Minnesota, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington) the eligibility system is shared by Medicaid and the Marketplace, resulting in an absence of file transfer issues. Most states that relied on healthcare.gov for Marketplace enrollment (including all FFM and FPM states, as well as two Federally-supported SBM states) indicated that initial file transfers, which were “flat files”, were unusable. Most of these states report that they began receiving usable account transfers (rather than the flat files) sometime between March and June of 2014 and most states have adopted system modifications or other solutions to process applications. At the time of the survey, a limited number of states reported that they were still unable to interface with the FFM. All but one of the SBM states indicated that the Medicaid agency was able to transfer files to the SBM and most of the states relying on the Federal Marketplace website (30 of the 36) also indicated that they were able to send files to the Marketplace. Others indicated that this functionality was being developed.

–

Application Processing Backlogs. The majority of states (31) reported that as of June 1, 2014 they had a backlog of Medicaid applications; the relative size of the backlog, while not collected across all states, varied substantially. States reported a variety of reasons for the backlogs including the sheer volume of applications; limited administrative capacity; large influx of applications from the FFM between March and June; pending verifications for income, citizenship and identity; incompatible data transferred from the FFM; and duplicate applications. Some states indicated that as of the date of the survey the backlog had been eliminated. Most states were seeing significant reductions in the backlogs and hoped to eliminate them with the exception of unresolved system or data issues. Thirteen states were asked by CMS to update their mitigation plans over the summer. As states worked through these backlogs, a number of them noted that a sizeable share of the applications yet to be processed were due to duplicate applications or applications from individuals who had started an application in one place but had completed a separate application in another way (e.g. started with an application at healthcare.gov but then applied again through the state Medicaid office.)

–

Preparation for Next Open Enrollment Period. States were asked to describe any issues on which they were focusing in preparation for the next Marketplace open enrollment period (beginning November 15, 2014, for coverage in January 2015). Many states have made or are making systems modifications to create a more seamless transition of applications from the Marketplace to the Medicaid agency. At least one state (North Dakota) changed from an assessment state to a “determination state” in which the Marketplace will make Medicaid eligibility determinations. Some states will be increasing staff resources and adding training for eligibility staff and for Marketplace navigators and other assisters. A few states are changing their Marketplace model: Nevada and Oregon are moving from SBMs to “Federally-supported SBMs” and will use healthcare.gov for Marketplace applications and enrollment; Idaho and New Mexico are working on efforts to move from Federally-supported SBMs to fully State-based Marketplaces; Idaho reported plans to make this transition for the next open enrollment period while New Mexico is planning to make this transition at a later date. A number of states mentioned developing policies and notices related to renewal (of Medicaid and Marketplace coverage) was also a focus; many states noted that this will be the first year handling both renewals and new enrollments since the ACA was implemented (as noted earlier, a number of states obtained waivers from CMS last year to delay renewals that would have otherwise occurred during the open enrollment period last year.) Several states were concerned about having adequate time to make the necessary adjustments to their systems, procedures or policies if the federal government makes changes.

|

TABLE 1: CHANGES TO ELIGIBILITY STANDARDS IN ALL 50 STATES AND DC, FY 2014 and 2015 |

||||||

| Eligibility Standard Changes | ||||||

| STATES | FY 2014 | FY 2015 | ||||

| (+) | (-) | (#) | (+) | (-) | (#) | |

| Alabama | ||||||

| Alaska | ||||||

| Arizona | X | X | ||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X | |||

| California | X | X | X | |||

| Colorado | X | X | ||||

| Connecticut | X | |||||

| Delaware | X | X | ||||

| DC | X | |||||

| Florida | X | |||||

| Georgia | ||||||

| Hawaii | X | X | ||||

| Idaho | ||||||

| Illinois | X | X | X | |||

| Indiana | X | X | X | |||

| Iowa | X | X | ||||

| Kansas | ||||||

| Kentucky | X | X | ||||

| Louisiana | X | X | X | X | ||

| Maine | X | X | ||||

| Maryland | X | X | ||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | ||||

| Michigan | X | X | ||||

| Minnesota | X | X | ||||

| Mississippi | ||||||

| Missouri | ||||||

| Montana | X | X | ||||

| Nebraska | ||||||

| Nevada | X | |||||

| New Hampshire | X | |||||

| New Jersey | X | X | ||||

| New Mexico | X | X | ||||

| New York | X | X | ||||

| North Carolina | ||||||

| North Dakota | X | X | ||||

| Ohio | X | |||||

| Oklahoma | X | |||||

| Oregon | X | X | ||||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | ||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | |||

| South Carolina | ||||||

| South Dakota | ||||||

| Tennessee | ||||||

| Texas | ||||||

| Utah | X | |||||

| Vermont | X | X | ||||

| Virginia | X | X | X | |||

| Washington | X | |||||

| West Virginia | X | |||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | ||||

| Wyoming | ||||||

| Totals | 31 | 4 | 24 | 8 | 0 | 6 |

|

NOTES: DC, HI, MA, and VT are counted as expanding coverage through the adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion even though these states had expanded full coverage to both adults and parents previously. |

||||||

Table 2: Eligibility Changes in the 50 States and the District of Columbia, FY 2014 and FY 20158 |

||

|

State |

Fiscal Year | Eligibility Changes |

| Alabama | 2014 | |

| 2015 | ||

| Alaska | 2014 | |

| 2015 | ||

| Arizona | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. As part of the expansion, the state lifted the enrollment cap for childless adults in its existing 1115 waiver program and transitioned this group to the new Medicaid expansion adult group. (affected 208,000 individuals) Adults (#): Eliminated Family Planning–only group in FY 2014. (affected 5,105 individuals) |

| 2015 | ||

| Arkansas | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented Medicaid expansion through an 1115 waiver as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. (affected 250,000 individuals) Elderly and Disabled Adults (-): Eliminated the Buy-in for Workers with Disabilities program December 31, 2013. Adults (#): Eliminated the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program in FY 2014. (affected 855 individuals) Adults (#): Eliminated Family Planning–only group in FY 2014. (affected 57,877 individuals) |

| 2015 | ||

| California | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning adults covered under its existing 1115 waiver program to the new Medicaid expansion adult group. Adults (#): Coverage of adults under the Health Care Coverage Initiative, a program that used Medicaid funds to cover adults with incomes between 133% and 200% FPL on a county-by-county basis under the state’s 1115 Bridge to Reform waiver, ended December 31, 2013. Children (+): Maintained eligibility for former foster care youth who age out of Medi-Cal at age 21 six months ahead of the ACA requirement. (affected approx. 166 individuals per month) |

| 2015 | Pregnant Women (+): Plan to implement a new affordability and benefit wrap program using Medicaid funding for pregnant women over 133% FPL. | |

| Colorado | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. This includes lifting the enrollment cap in their existing 1115 waiver and transitioning those covered under this program to the new Medicaid expansion adult group. Children (+): Implemented continuous eligibility for children. (affected 4,286 individuals) |

| 2015 | Children (+): Implement the option to eliminate the 5-year bar on eligibility for legally-residing immigrant children. (estimated to affect 1,699 individuals) | |

| Connecticut | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning adults covered under their Low-Income Adult waiver program to the new Medicaid expansion adult group. Adults (nc): Coverage for parents up to 201% FPL was maintained. |

| 2015 | ||

| Delaware | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning adults covered under their existing 1115 waiver to the new Medicaid expansion adult group. (affected 6,500 individuals) Adults (#): Eliminated Family Planning–only group. (affected 2,072 individuals) |

| 2015 | ||

| District of Columbia | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning adults covered under their existing early expansion state plan group to the new Medicaid expansion adult group. Adults (nc): Coverage for its existing 1115 waiver for adults above 138% FPL was maintained. Adults (nc): Implemented Medicaid enrollment suspension for incarcerated adults. |

| 2015 | Adults (nc): Plan to transition adults with incomes above 138% FPL from a Medicaid waiver to Medicaid state plan. (estimated to affect 6,258 individuals) | |

| Florida | 2014 | Elderly and Disabled (+): Increased the minimum monthly maintenance income allowance and excess standard for community spouses of institutionalized people. (The number of nursing home residents eligible for Medicaid is also affected by 2014 cost of living adjustments and increases in the average private pay nursing home rate.) |

| 2015 | ||

| Georgia | 2014 | |

| 2015 | ||

| Hawaii | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, for adults up to 138% FPL and transferred some existing waiver populations to Medicaid expansion. Adults (#): Eliminated Medically Needy Spend-down coverage for non-elderly non-disabled adults in FY 2014. |

| 2015 | ||

| Idaho | 2014 | |

| 2015 | ||

| Illinois | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. (affected 385,000 individuals) Adults (#): Medically Needy Spend-down coverage for parents was eliminated. (affected10,800 individuals) |

| 2015 | Adults (nc): Plan to transition The state’s existing 1115 waiver (Cook County Care) was extended through June 2014; adults will be transitioned to the new Medicaid expansion adult group July 2014. Adults (#): Illinois is in the final year of operating its Family Planning waiver, which is being phased out. (estimated to affect 65,000 individuals) |

|

| Indiana | 2014 | Adults (#): Reduced income levels for the state’s existing 1115 waiver (HIP), for adults from 200% to 100% FPL per waiver renewal. (affected 11,900 individuals) Adults (+): HIP enrollment cap for childless adults under the Healthy Indiana Plan was increased per waiver renewal. Elderly and Disabled (-): Converted from 209(b) to 1634 for aged, blind and disabled. As a result 209(b) related spend-down is no longer available. Some of these individuals with income above 100% FPL are expected to have other coverage options in the Marketplace, under Medicaid through the Medicare Savings Program, or under the new BPHC Medicaid program (described below), but some are expected to lose coverage. (affected 31,500 individuals) Elderly and Disabled (+): Increased the income eligibility level for the Medicare Savings Program. (affected 47,000 individuals) Elderly and Disabled (+): Implemented a new program, Behavioral and Primary Healthcare Coordination (BPHC) under a 1915i state plan option. Adults with serious mental illness with income up to 300% FPL that do not otherwise qualify for Medicaid coverage or other third party coverage will qualify for full Medicaid benefits. |

| 2015 | Adults (Proposed): The state has submitted a waiver proposal, HIP 2.0, which would use the state’s existing HIP program as a platform for an alternative Medicaid expansion, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. The waiver has not been approved by CMS at the time of this report. | |

| Iowa | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, through an 1115 waiver (Iowa Health and Wellness Plan), increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning adults covered under their existing 1115 waiver (IowaCare) to the new Medicaid expansion adult group. Adults (#): The state’s existing 1115 waiver (IowaCare) which covered adults up to 200% FPL expired December 31, 2013. |

| 2015 | ||

| Kansas | 2014 | |

| 2015 | ||

| Kentucky | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. |

| 2015 | Adults (#): Plan to eliminate Medically Needy Spend-down coverage for non-elderly non-disabled adults and optional Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program in Jan. 2015. (estimated to affect 4,400 individuals and 480 individuals respectively) | |

| Louisiana | 2014 | Elderly and Disabled (+): Implemented spend-down eligibility for four HCBS waivers (allows individuals to spend down to 300% federal SSI waiver eligibility level). Elderly and Disabled (-): No longer determine eligibility for the optional coverage of aged and disabled individuals under 100% FPL. They are referred to SSA for determination under our 1634 agreement. (Closed 8,000 cases) Elderly and Disabled (-): Reduced the income and resource standards for TWWIIA Basic coverage group (Medicaid Purchase Plan). Elderly and Disabled (+): Added optional coverage group to implement the State Provisional Medicaid Program which will provide interim Medicaid-only benefits to eligible individuals until such time that a decision has been rendered on their SSI cash assistance application pending with the Social Security Administration. Pregnant Women (#): Eliminated optional coverage of pregnant women with incomes between 133% and 200% FPL. Pregnant women over 133% moved to CHIP. |

| 2015 | Adults (#): Plan to eliminate Family Planning waiver for those over 138% FPL. Those with income below 133% FPL will move from waiver to state plan. (7,200 individuals) | |

| Maine | 2014 | Adults (#): Reduced parent/caretaker income levels from 133% to 100% FPL. (affected 14,000 individuals) Adults (-): Maine’s 1115 waiver that covered adults without dependent children up to 100% FPL expired. (affected 9,000 individuals) |

| 2015 | ||

| Maryland | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning adults covered under their existing 1115 waiver to the new Medicaid expansion coverage group. Adults (#): Eliminated Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program in FY 2014. |

| 2015 | ||

| Massachusetts | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, which covers adults up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning approximately 256,207 adults covered under their existing 1115 waiver program to the new adult expansion group. Adults (#): The state eliminated Medicaid waiver coverage for some adults with income over 138% FPL. Adults (+): The state is using Medicaid funds to provide premium assistance to those previously covered under the state’s Medicaid waiver with incomes between 138% FPL and 300% FPL using Medicaid dollars. Other (+): Cover adults 19 and 20 up to 150% FPL in MassHealth Standard. (27,300) |

| 2015 | ||

| Michigan | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of April 1, 2014, through an 1115 waiver, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning adults covered under an existing 1115 waiver program to the new adult expansion group. (350,000; 50,000 of whom were eligible for the state’s existing 1115 waiver) Adults (#): Eliminated Family Planning –only group in FY 2014. (30,000) |

| 2015 | ||

| Minnesota | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, which covers individuals up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning some individuals from their existing MinnesotaCare 1115 waiver program to the new adult expansion group as well as those covered by their early expansion Medicaid state plan option. Other (+): Medically needy income level for parents/caretakers, children and pregnant women increased to 133% FPL. Adults (nc): Waiver renewal maintains MinnesotaCare coverage for 138 to 200% FPL group. Adults (#): Reduced income level for MinnesotaCare adults from 275% to 200% FPL. |

| 2015 | Other (not Medicaid): Minnesota expects to transition to a Basic Health Plan for 2015. | |

| Mississippi | 2014 | |

| 2015 | ||

| Missouri | 2014 | |

| 2015 | ||

| Montana | 2014 | Other (+): Raised cap on 1115 MHSP waiver from 800 to 2000 adults with SMI. |

| 2015 | Other (+): Raised cap on 1115 MHSP waiver from 2000 to 6000 adults with SMI. | |

| Nebraska | 2014 | |

| 2015 | ||

| Nevada | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. (88,407 childless adults and 36,202 parents/caretakers) |

| 2015 | ||

| New Hampshire | 2014 | |

| 2015 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of July 1, 2014, through an 1115 waiver (New Hampshire Health Protection Program), increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. (estimated to affect 50,000 individuals) | |

| New Jersey | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning adults covered under their existing 1115 waiver to the new Medicaid expansion coverage group. (affected 100,000 individuals) |

| 2015 | Medically Needy (+): New Jersey will be implementing the “Miller Trust” option to enable additional individuals to qualify for community-based Long Term Supports and Services.9 | |

| New Mexico | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning some adults covered under their existing 1115 waiver (State Coverage Initiative) to the new Medicaid expansion coverage group. (affected 31,500 individuals) Adults (#): Eliminated 1115 waiver coverage (State Coverage Initiative) between 138% FPL and 200% FPL. |

| 2015 | Adults (#): Plan to eliminate Family Planning–only group in FY 2015. (estimated to affect 37,400 individuals) | |

| New York | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. As part of implementing the Medicaid expansion, the state transitioned some of adults covered under their existing 1115 waiver (Family Health Plus) to the new Medicaid expansion coverage group. Adults (#): Eliminated 1115 waiver coverage (Family Health Plus) for adults with incomes above 138% FPL. Adults (+): The state is pursuing waiver authority to establish the Qualified Health Plans Premium Assistance Program, which would provide premium assistance to those previously covered under the state’s Medicaid waiver with income between 138% FPL and 150% FPL using Medicaid dollars. (affected approx. 35,000 individuals) |

| 2015 | Other (Not Medicaid): Plans to start the Basic Health Plan with certain immigrants, who are currently paid for with state-only funds, with income up to 200% FPL. New York will then expand to an estimated 200,000 more people with incomes between 138% – 200% FPL. | |

| North Carolina | 2014 | |

| 2015 | ||

| North Dakota | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. (affected 10,000 individuals) Adults (#): Eliminated Medically Needy Spend-down coverage for non-elderly non-disabled adults in FY 2014. |

| 2015 | ||

| Ohio | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning some adults covered under their existing 1115 waiver (Cuyahoga County MetroHealth) to the new Medicaid expansion coverage group. |

| 2015 | ||

| Oklahoma | 2014 | Adults (#): As part of a one-year extension, eligibility for individuals under the Individual Plan will be reduced from 200% FPL to 100% FPL. (affected 8,000 individuals) Pregnant Women (#): Reduced eligibility level for pregnant women down to 138% FPL. (affected 4,731 individuals) Adults (#): Reduced family planning waiver from 185% to 138% FPL. (affected 8,762 individuals) |

| 2015 | ||

| Oregon | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. As part of implementing the Medicaid expansion, the state transitioned adults covered under their existing 1115 waiver to the new Medicaid expansion coverage group. (affected 60,000 individuals) Adults & Children (#): Eliminated Medicaid Premium Assistance programs for adults and children with incomes below 200% FPL. (affected 5000 adults and 12,400 children) |

| 2015 | ||

| Pennsylvania | 2014 | |

| 2015 | Adults (+): Implementing the Healthy PA Section 1115 waiver January 1, 2015,which increases Medicaid eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. (estimated to affect 600,000 individuals) Adults (#): Plan to eliminate Medically Needy Spend-down coverage for non-elderly non-disabled adults. (estimated to affect 3,119 individuals) Adults (#): Plan to eliminate Family Planning–only group. (estimated to affect 90,000 individuals) |

|

| Rhode Island | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning adults covered under their existing 1115 waiver to the new Medicaid expansion coverage group. (affected 50,000 individuals) Parents (#): Eliminated Medicaid coverage for parents from 138% to 175% FPL. (affected 4,000 individuals) |

| 2015 | Pregnant Women (+): State will be exploring a Premium Assistance Program for Pregnant women over 133% FPL who wish to enroll in a qualified health plan. | |

| South Carolina | 2014 | |

| 2015 | ||

| South Dakota | 2014 | |

| 2015 | ||

| Tennessee | 2014 | |

| 2015 | ||

| Texas | 2014 | |

| 2015 | ||

| Utah | 2014 | Adults (#): Reduced eligibility for the state’s existing 1115 waiver (PCN) from 150% to 100% FPL. Enrollment cap remains in place. |

| 2015 | ||

| Vermont | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, covering adults up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning some of the adults covered under their existing 1115 waiver to the new Medicaid expansion coverage group. Adults (#): Reduced Medicaid eligibility levels to 138% FPL. Adults (+): Implementing Vermont Premium Assistance which uses Medicaid funds to provide subsidies for Marketplace coverage in addition to marketplace subsidies. Also implementing the Vermont cost sharing reduction subsidies that reduce copays and deductibles for Marketplace products for individuals and families with incomes below 300% FPL.Children (nc); Increased income standard for children in Medicaid state plan to incorporate waiver expansion group. |

| 2015 | Other (nc): Submitted SPA to disregard asset tests for non-ABD medically needy. | |

| Virginia | 2014 | Adults (#): Reduced income eligibility for Family Planning waiver to 100% FPL. |

| 2015 | Adults (#): Plan to restore income eligibility for Family Planning waiver to 200% FPL.Adults (+): Plan to implement 1115 waiver with limited benefits to extend coverage to adults with incomes below 100% FPL with severe mental illness. | |

| Washington | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. This includes transitioning adults covered under their existing 1115 waiver to the new Medicaid expansion coverage group.(affected 390,000 individuals) |

| 2015 | ||

| West Virginia | 2014 | Adults (+): Implemented the Medicaid expansion as of Jan. 2014, increasing eligibility for adults up to 138% FPL. |

| 2015 | ||

| Wisconsin | 2014 | Adults (+): Eliminated the enrollment cap that was part of the previous waiver for Childless Adults up to 100% FPL. (affecting 93,000 individuals) Adults (#): Reduced the income limit for parents/caretakers and childless adults from 200% FPL to 100% FPL. (affecting 55,000 individuals) |

| 2015 | ||

| Wyoming | 2014 | |

| 2015 | ||

Delivery System Reforms

Use of Managed Care

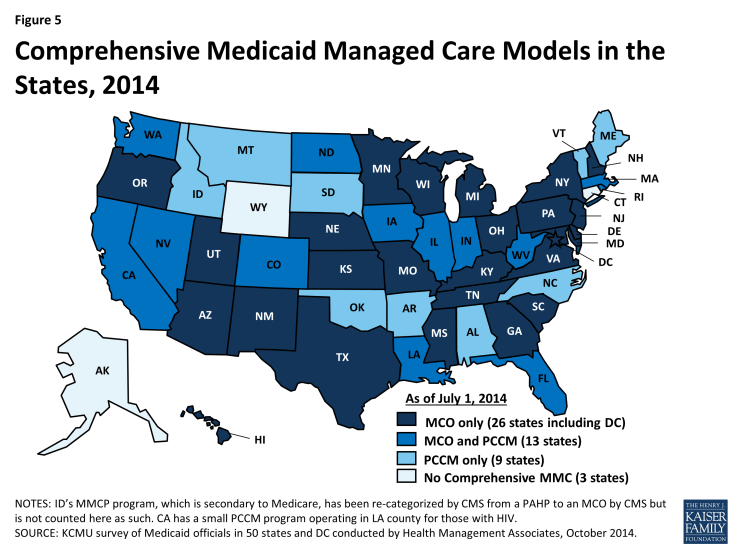

Managed care has become the main delivery system for Medicaid in most states, as Medicaid programs increasingly have turned to managed care as a means to help assure access, improve quality and achieve budget certainty. As of July 2014, all states except three – Alaska, Connecticut and Wyoming – had in place some form of managed care. Across the 48 states with some form of managed care, a total of 39 states including DC had contracts with comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs); 22 states administered a Primary Care Case Management (PCCM) program, a managed fee-for-service based system in which beneficiaries are enrolled with a primary care providers who are paid a small fee to provide case management services in addition to primary care. Of the 48 states that operate some form of managed care, a total of 13 states operate both MCOs and a PCCM program while 26 states (including DC) operate MCOs only and nine states operate PCCM programs only.1 (Figure 5) In addition, 20 states contracted with one or more limited-benefit risk-based prepaid health plans to provide behavioral health, dental care, maternity care, non-emergency medical transportation, or other benefits.

The share of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in MCOs, PCCM programs or remaining in fee-for-service varies widely by state. The share enrolled in MCOs, however, has steadily increased as states have expanded their managed care programs to new regions, to new populations and made MCO enrollment mandatory for additional eligibility groups. Among the 39 states (including DC) with MCOs, 16 states reported that over 75 percent of their beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs as of July 1, 2014.

Notable shifts to increase the use of risk-based managed care during FY 2014 and FY 2015 include two states (New Hampshire and North Dakota) that implemented new risk-based managed care programs. In addition, states like Florida and New Mexico, which have many years of experience with managed care, implemented new expansive statewide managed care programs in FY 2014. Six states (Florida, Indiana, Louisiana, Oregon, South Carolina, and Utah) have ended or plan to end their PCCM programs in FY 2014 or FY 2015 and are transitioning these groups to risk-based managed care organizations. However, not every state has moved in this direction. For example, Vermont currently operates an enhanced-PCCM program and is expanding its use of ACOs as part of its State Innovation Model (SIM) grant.2 Connecticut terminated its MCO contracts in 2012 and now operates its program on a fee-for-service basis using four administrative services only (ASO) entities to manage medical, behavioral health, dental and non-emergency transportation services. The ASOs are accountable for specific performance metrics common to managed care, but the state does not describe its system as managed care.

Risk Based Managed Care Expansions

In both FY 2014 and in FY 2015, states continued to take actions to increase enrollment in managed care. Of the 39 states (including DC) with MCOs, a total of 34 states indicated that they made specific policy changes to increase the number of enrollees in MCOs; no states with MCOs took any action designed to restrict MCO enrollment. The most common strategy was to expand voluntary or mandatory enrollment to additional eligibility groups (25 states in FY 2014 and 19 states in FY 2015.) The eligibility group most commonly added to MCOs was the newly eligible adult group in states adopting the ACA Medicaid expansion.

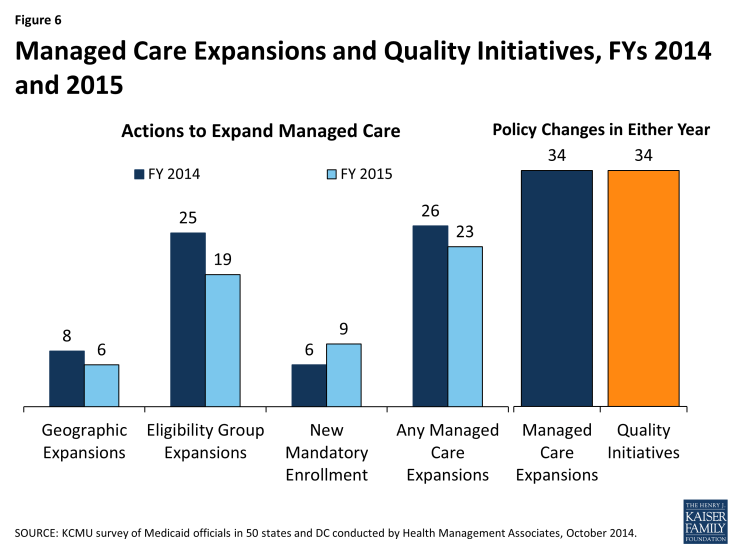

Other commonly noted eligibility groups added to managed care included children (such as those in foster care, adoption subsidy or juvenile justice systems in Florida, Georgia, Nebraska, Texas, and Virginia as well as other groups of children in California, Florida, and Mississippi); those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (California, Florida, Illinois, New York, Ohio, Rhode Island, South Carolina and Virginia); and other elderly individuals or those with disabilities (Indiana, Louisiana, Nebraska, New York, New Jersey, Ohio, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia). In addition, six states made enrollment mandatory for specific eligibility groups in FY 2014, and nine states are doing so in FY 2015. Geographic expansions for MCO service areas occurred in eight states in FY 2014, and in six states in FY 2015. (Figure 6)

Managed Care Quality. As states expand risk-based managed care, they continue to undertake efforts to improve managed care quality and outcomes. New quality improvement initiatives were implemented in 34 states in either FY 2014 or FY 2015. These initiatives include the use of new quality metrics focused on specific conditions (e.g., behavioral health conditions, childhood obesity, hypertension, asthma, and diabetes) and the addition or enhancement of pay-for-performance arrangements, including changes in amounts withheld from monthly capitation payments that are at risk based on each MCO’s performance on specified quality measures. In addition, some states are introducing or expanding public reporting of quality metrics.

Additional information on states that reported managed care changes implemented in FY 2014 or planned for FY 2015 can be found in Table 3.

Primary Care Case Management Programs

Of the 22 states with PCCM programs, six indicated they enacted policies to increase PCCM enrollment in FY 2014 or FY 2015. The state actions include: Arkansas implemented the Delta Pilot Program, an enhanced PCCM. Colorado and Rhode Island are expanding enrollment in their PCCM programs as part of integrated care initiatives for those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid; Rhode Island is also expanding enrollment in their PCCM program for other populations who are elderly or disabled. Iowa is using the PCCM for the expansion of the Wellness Plan, part of their ACA Medicaid expansion waiver. Nevada has launched a new PCCM model targeted to those currently in fee-for-service with co-morbid conditions (about 39,000 members.)

In contrast, eight states (Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Oregon, Utah and South Carolina) have taken actions that decreased enrollment in their PCCM programs.3 Six of these states (Florida, Indiana, Louisiana, Oregon, South Carolina, and Utah) have ended or plan to end their PCCM programs and transition PCCM enrollees to risk-based managed care. In June 2014, Illinois began transitioning 1.5 million PCCM enrollees to “managed care entities” in the five mandatory enrollment regions. In Oklahoma, effective July 2014 individuals with creditable primary coverage are no longer eligible for the SoonerCare Choice PCCM program.

| Managed Care Administrative Policies |

|

MCO Rate-Setting. Federal law requires that state Medicaid programs pay MCOs actuarially sound capitation rates. As the role of capitated managed care has increased, states have paid greater attention to the rate-setting process. States indicated a range of approaches to setting rates for MCOs to achieve actuarially sound rates, often involving a combination of strategies. As of July 2014, the 39 states with MCOs reported using one or more of the following methods in setting actuarially sound rates – administrative-rate setting (29 states), negotiation (12 states), competitive bidding with an actuarially defined range (11 states.) Increasingly, states are contracting with actuarial firms to assist in the rate-setting process as the state administratively sets, bids or negotiates the rates.–

–

Minimum Loss Ratios. For an MCO, the proportion of total per member per month capitation payments that is spent on clinical services and for quality improvement is known as the Medical Loss Ratio (MLR). Thus, the MLR represents the share of dollars that MCOs spend on providing and improving patient care compared to administrative costs, which include executive salaries, overhead, and marketing, and on profits. State insurance regulators commonly set a minimum MLR for commercial health plans, and the ACA mandates a minimum MLR for Medicare Advantage plans and for qualified health plans (QHPs) participating in the health insurance Marketplaces. State Medicaid programs are allowed to set a MLR for Medicaid health plans. As of July 2014, 27 of the 39 states that contracted with comprehensive risk-based MCOs specified a minimum MLR for all or some plans, and 12 states did not have an MLR requirement. Twenty-two of the 27 states with a MLR requirement always applied it and five states applied it on a limited basis (e.g., for the new ACA Medicaid expansion population.) State Medicaid MLRs vary, though most commonly are set at 85 percent. Some states noted that MLRs varied by type of plan or population.–

–

Auto-enrollment. Beneficiaries who are required to enroll in MCOs must be offered a choice of at least two plans. Those who do not select a plan are auto-enrolled in a plan. Of the 39 states with comprehensive risk-based MCOs, all except one required that some or all beneficiaries to enroll in an MCO. (The exception is North Dakota, which has only one health plan.) The proportion of beneficiaries who are auto-enrolled varies widely across states. Five states had auto-enrollment rates of 10 percent or less, while six states auto-enrolled between 70 percent and 80 percent of new MCO enrollees.4 State’s auto-enrollment algorithms also vary, with about half rotating enrollments randomly across plans, and others incorporating a range of factors, including previous connection of the beneficiary or family members to a primary care provider or total plan enrollment. Some states use or plan to use MCO performance on specified quality measures in auto-assigning new enrollees, with higher performing plans receiving some or all auto-enrollments.

|

TABLE 3: MANAGED CARE INITIATIVES TAKEN IN ALL 50 STATES AND DC, FY 2014 and 2015 |

||||||||||

| States | Geographic Expansions | Add Eligibility Groups | New Mandatory Enrollment | Expansions of Managed Care | Quality Initiatives in Managed Care | |||||

| 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | Either Year | Either Year | |

| Alabama | ||||||||||

| Alaska | ||||||||||

| Arizona | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Arkansas | ||||||||||

| California | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Colorado | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Connecticut | ||||||||||

| Delaware | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| DC | X | |||||||||

| Florida | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Georgia | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Hawaii | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Idaho | X | |||||||||

| Illinois | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Indiana | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Iowa | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Kansas | ||||||||||

| Kentucky | X | X | X | |||||||

| Louisiana | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Maine | ||||||||||

| Maryland | X | |||||||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Michigan | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Minnesota | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Mississippi | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Missouri | ||||||||||

| Montana | ||||||||||

| Nebraska | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Nevada | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| New Hampshire | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| New York | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| North Carolina | ||||||||||

| North Dakota | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Ohio | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Oklahoma | ||||||||||

| Oregon | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| South Carolina | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| South Dakota | ||||||||||

| Tennessee | X | |||||||||

| Texas | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Utah | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Vermont | ||||||||||

| Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Washington | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| West Virginia | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Wyoming | ||||||||||

| Totals | 8 | 6 | 25 | 19 | 6 | 9 | 26 | 23 | 34 | 34 |

| NOTES: States were asked if they expanded managed care (comprehensive risk-based managed care) to new regions, new populations, increasing the use of mandatory enrollment or the implementation of new managed care plans. States reported separately if they implemented new quality initiatives in managed care plans as well. SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2014. |

||||||||||

Other Delivery System and Payment Reform

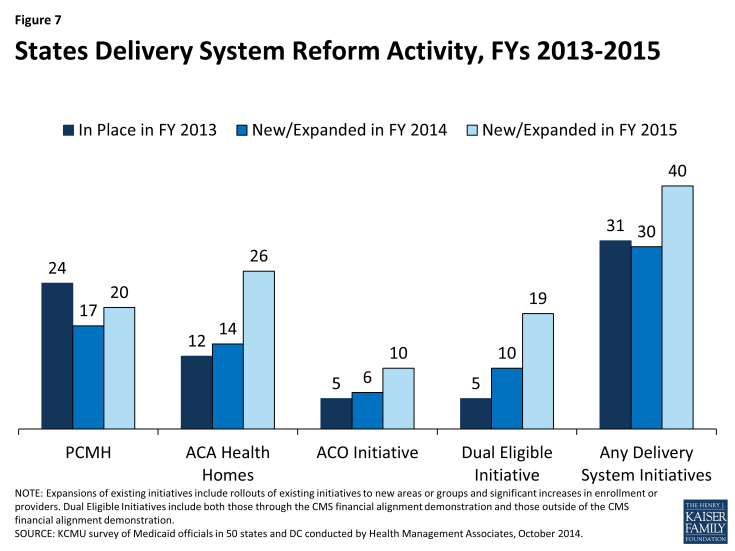

States are increasingly interested in new approaches that hold the promise of improving health outcomes and constraining costs by redesigning the way that care is delivered and paid for. These emerging models which seek to align payment and delivery systems to reward quality and promote more integrated care include initiatives to coordinate physical and behavioral health care, efforts to coordinate acute and long-term care and care management approaches that target persons with multiple chronic conditions. These delivery system and payment reform approaches are sometimes implemented outside of managed care and sometimes within it. This year’s survey asked states which delivery system and payment reform models were in place in FY 2013, or if they had adopted or were enhancing such models in FY 2014 or FY 2015. (Figure 7)

Patient-Centered Medicaid Homes (PCMH). In 2007, four leading physician groups released key principles that define a PCMH: (1) the personal physician leads a team that is collectively responsible for the patient’s ongoing care; (2) the physician is responsible for the whole person in all stages of life; (3) care is coordinated and/or integrated; (4) quality and safety are hallmarks of a medical home; (5) enhanced access to care is available through all systems; and (6) payment appropriately recognizes the added value to the patient. In addition, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) has issued specific standards to be recognized as a PCMH.5 In this survey, 24 states said that PCMHs were “in place” in FY 2013, 17 states reported having adopted or expanding PCMHs in FY 2014 and 20 states indicated plans to do so in FY 2015.

| Patient-Centered Medical Home Initiatives |

|

Connecticut PCMH Initiative: The Connecticut Department of Social Services is investing significant resources to help primary care practices obtain PCMH recognition from the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). Practices on the “glide path” toward recognition receive technical assistance from Community Health Network of Connecticut, Inc. (CHNCT). Practices that have received recognition are eligible for financial incentives including enhanced fee-for-service payments and retrospective payments for meeting benchmarks on identified quality measures; practices on the glide path receive prorated enhanced fee for service payments based upon their progress on the glide path but are not eligible for quality payments at this time. In this year’s survey, the state reported that approximately one-third of Connecticut’s Medicaid population was assigned to a PCMH with a plan to expand to all enrollees in the future.

–

Virginia’s PCMH Requirement for MCOs: Virginia modified its PCMH requirement in the FY 2014 Medallion II managed care contract (2013-2014) by implementing instead the Medallion Care Systems Partnership. This initiative allows MCOs opportunities to expand and test different methodologies of payment and incentives within the medical home model to advance quality and member outcomes while allowing for small scale pilots of innovative payment reform models.

|

Health Homes. Section 2703 of the ACA provides a new state plan option for Medicaid programs to establish “health homes,” designed to be person-centered systems of care that facilitate access to and coordination of the full array of primary and acute physical health services, behavioral health care, and community-based long-term services and supports, for beneficiaries who have at least two chronic conditions, or one and at risk of a second or a serious and persistent mental health condition. To implement a health home program, a state must obtain CMS approval of a state plan amendment (SPA). A 90 percent federal match rate is available for qualified expenditures for health home services for the first eight quarters of a state’s program.6 The ACA defines health home services to include: comprehensive care management; care coordination and health promotion; transitional care from inpatient to other settings; support for patients and families; referral to community and social support services; and use of Health Information Technology (HIT) to link services.7 In this survey, 12 states said that health homes were “in place” in FY 2013, 14 states reported having adopted or expanded health homes in FY 2014 and 26 states reported plans to do so in FY 2015. Many states noted that they were focusing their health home programs on populations with behavioral health conditions as well as populations with multiple chronic conditions.

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). An ACO is a provider-led group of health care providers that agree to share responsibility for the delivery of care to and health outcomes of a defined group of people and the cost of their care. The organizational structure of ACOs varies, but all ACOs include primary and specialty care physicians and at least one hospital. Providers in an ACO are expected to coordinate care for their shared patients to enhance quality and efficiency, and the ACO as an entity is accountable for that care. An ACO that meets quality performance standards that have been set by the payer and achieves savings relative to a benchmark can share savings with the payer and distribute them among its providers. Some states that are pursuing ACOs for Medicaid beneficiaries are building on existing care delivery programs (e.g., PCCM, medical homes, MCOs) which already involve some degree of coordination among providers and may have some of the infrastructure (e.g., electronic medical records) necessary to support coordination among ACO providers. States use different terms for their Medicaid ACO initiatives, such as Coordinated Care Organizations (CCOs) in Oregon and Accountable Care Collaboratives (ACCs) in Colorado.8

In this survey, five states reported that ACOs were “in place” in FY 2013, six states reported adopting or expanding ACOs in FY 2014 and ten states reported such activity in FY 2015. Some states have sought or are seeking to reorganize some or all of their Medicaid delivery system into ACOs (Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Oregon, Utah, and Vermont,) while ACO efforts in other states have been more provider-driven (California, New Jersey, and South Carolina.) Also, a number of states noted that their ACO initiatives are part of larger State Innovation Model (SIM) grants that involve multiple payers.

Care Coordination and Integration of Care for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries. Coordinating care for those dually-eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (dual eligible beneficiaries) is a significant issue for Medicaid programs. Dual eligible beneficiaries comprise just 14 percent of Medicaid enrollees but accounted for 36 percent of Medicaid spending in 2010. For Medicare, dual eligible beneficiaries accounted for 20 percent of all enrollees but 33 percent of all spending in 2009.9 About 65 percent of all spending for dual eligible individuals is for long-term services and supports, covered largely by Medicaid, and about 25 percent is for acute care services, primarily covered by Medicare.10 These individuals tend to have significant health needs, a high prevalence of chronic conditions and substantial use of long-term services and supports.

Prior to the ACA, coordination of care for individuals with dual enrollment in Medicaid and Medicare had been difficult to pursue for states in part because of misalignment between Medicare and Medicaid laws. In addition, when states did develop approaches to better coordinate care, any resulting savings from improvements in acute care (such as reduced inpatient admissions, re-admissions and emergency room visits) most often accrued to Medicare and were not shared with state Medicaid programs. Under Section 2602 of the ACA, CMS established the Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office (MMCO) and initiated financial alignment demonstrations with interested states seeking to coordinate and improve care and control costs for those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

In this survey, five states indicated that initiatives to coordinate care for dual eligible beneficiaries were in place in FY 2013; all of these initiatives were outside the CMS financial alignment demonstration and centered on enrolling this population in comprehensive MCOs or in managed long-term care plans. In FY 2014, ten states noted new or expanded initiatives for dual eligible beneficiaries, five of which related to the implementation of a financial alignment demonstration. In FY 2015, 19 states noted plans to implement an initiative focused on this population, of which 13 planned to implement a financial alignment demonstration.11 Initiatives outside of the financial alignment demonstrations included alignment of Medicare Advantage Special Needs Plans for dual eligible beneficiaries (D-SNPs) with Medicaid MCOs and enrollment of dual eligible beneficiaries in comprehensive Medicaid MCOs (for acute care services) or managed long-term care.

Additional information on states that reported delivery system and payment reform initiatives implemented in FY 2014 or planned for FY 2015 can be found in Table 4.

| Other Emerging Delivery System and Payment Reforms |

|

This year’s survey asked states about two emerging delivery system and payment reform initiatives: Episode of Care Payments and DSRIP programs, described below. Aside from these two initiatives, states also commonly mentioned payment reforms that focused on reducing preventable admissions and readmissions, hospital acquired conditions, and elective early deliveries.

–