Integrating Physical and Behavioral Health Care: Promising Medicaid Models

Introduction

In 2006, a report issued by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors cited research showing that adults with serious mental illness (SMI) die, on average, 25 years earlier than the general population, and that the rates of illness and death in this population have been on the rise.1 Much of the excess mortality among people with SMI is explained by their disproportionately high rates of mortality from the same preventable conditions, including cardiovascular and pulmonary disease, that are among the leading causes of death in the general population. People with SMI also have higher rates of modifiable risk factors for these conditions, such as smoking and obesity; experience higher rates of homelessness, poverty, and other causes of vulnerability; and face symptoms associated with SMI, such as disorganized thought and decreased motivation, that impair compliance and self-care. Further, co-occurring substance use disorders are prevalent among individuals with SMI. But despite the high rate of substance abuse comorbidities among people with SMI, the mental health and substance abuse systems are often entirely separate, and both are segregated from the physical health system. This fragmentation of the health care system can lead to inappropriate care, disjointed care, gaps in care, and redundant care, and can result in increased health care costs.

Medicaid, the nation’s public health insurance program for low-income people, is the chief source of coverage for low-income individuals with disabilities, including many who have behavioral health needs. Mental illness is more than twice as prevalent among Medicaid beneficiaries as it is in the general population, and roughly 49% of Medicaid beneficiaries with disabilities have a psychiatric illness.2 As might be expected given its coverage role, Medicaid is also a major source of financing for mental health services. The Medicaid program finances more than one-quarter of the nation’s spending for behavioral health care and it is, by far, the largest single source of funding for public mental health services.3 Mental health care is an important driver of Medicaid costs. Among the highest-cost 5% of Medicaid-only* enrollees with disabilities, three of the five most prevalent disease pairs include psychiatric illness. The most common disease pair is cardiovascular disease and psychiatric illness, found in 40% of the Medicaid beneficiaries in this top spending group.4

Given the prevalence of mental illness in the Medicaid population, the high level of Medicaid spending on behavioral health care, and the adverse impact that uncoordinated care can have on the physical health of people with SMI and, thus, on total spending, it is not surprising that Medicaid directors consider initiatives to integrate physical and behavioral health care to be one of their top priorities. According to a 50-state Medicaid survey conducted by the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured in 2012, a large majority of states had initiatives underway in state fiscal year (FY) 2012 or planned for FY 2013 to better coordinate care between the two systems.5 The Affordable Care Act (ACA) also places a heavy emphasis on this issue, responding to shortcomings of the current fragmented systems of care, and setting forth expectations for better outcomes and reduced costs for those with comorbid conditions. In addition to increasing access to care by expanding Medicaid and private health coverage, the ACA specifically includes mental health and substance use disorder services as one of the ten categories of required “essential health benefits,” and the law requires parity between the mental and physical health benefits covered by health plans. The ACA also establishes new mechanisms and funding opportunities designed to promote coordinated and person-centered care, such as a new Medicaid option for health homes, a large trust fund dedicated to expanding health center services and capacity, and initiatives to develop Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs).

Interested in both improving care and controlling Medicaid costs, and aided by federal reforms and investment, states, health plans and provider systems are increasingly developing and implementing strategies to better integrate physical and behavioral health services. Efforts to date have taken a variety of forms, but two central themes emerge. One is the importance of identifying all of a patient’s health care needs regardless of why or through what door he or she entered the health care system. The other is the broad goal of person-centered care and the specific role of care coordination in achieving it. This brief examines several approaches that state Medicaid programs, health plans, and providers are pursuing, ranging from relatively modest steps to improve coordination between the physical and behavioral health systems, to more ambitious efforts to fully integrate them.

A Continuum of Approaches to Physical and Behavioral Health Care Integration

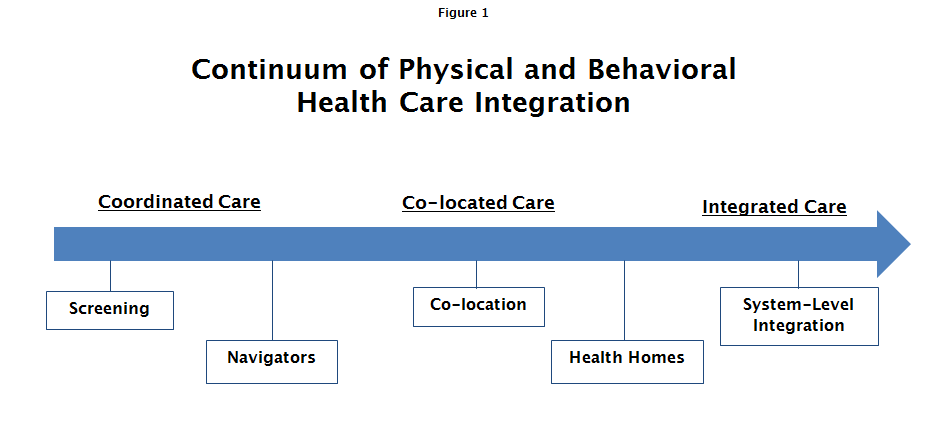

In a recent paper on integrated physical and behavioral health (PH/BH) care, the SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions (CIHS) outlined a continuum of collaboration/integration, ranging from separate systems and settings with little communication between them, to PH/BH co-location with some degree of collaboration in screening and treatment planning, to fully integrated care, manifested when behavioral and physical health care providers and other providers function as a true team in a shared practice and with a shared vision, and both providers and patients experience the operation as a single system treating the whole person.6 (Figure 1)

Considering different strategies as stages along an integration continuum can help states, health plans, and providers assess where they are currently and determine what next steps they might take to further integrate the care that Medicaid beneficiaries receive, even if full integration cannot be achieved.

Nationwide, many state agencies, plans and providers are implementing PH/BH integration strategies in Medicaid that can be mapped loosely to the different levels of collaboration/integration identified in the SAMHSA-HRSA framework. This brief highlights five strategies currently underway in Medicaid: universal screening; navigators; co-location; health homes; and system-level integration. These models may offer those seeking to advance PH/BH care integration in Medicaid promising directions for change.

1. Universal Screening

Box 1: Screening, Brief Intervention, Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) is a comprehensive approach to identifying persons with or at risk of substance use disorders who present at primary care centers, emergency departments, trauma centers, and other community settings. Screening at the time of intake to assess the severity of substance use and determine the appropriate level of treatment affords the opportunity for early intervention, before more serious consequences occur. Brief Intervention focuses on increasing the individual’s awareness of his or her substance use problem and his or her motivation to change the behavior. Referral to Treatment provides access to the needed specialty care. SAMHSA reports a growing body of evidence in support of SBIRT’s clinical and cost-effectiveness in identifying and treating risky alcohol and tobacco use.

The foundation of integrated care is a holistic view of the individual and personal health as complex, integrated systems, rather than a simple sum of independent body systems. It follows that integrated care begins with an assessment of patients for conditions and/or the risk of developing conditions in addition to the ones they present for. As a practical matter, this means the adoption by primary health care providers of tools to screen for behavioral health needs and, by the same token, the adoption by behavioral health providers of tools to screen for physical health needs. Today, it is more common for primary care providers (PCP) to screen for behavioral health needs than for behavioral health providers to screen for physical health needs.

Numerous studies have documented the effectiveness of screening for behavioral health disorders in primary care settings, and a number of evidence-based tools to screen for depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders are quick and easy to administer and are available in the public domain.7 Screening, Brief Intervention, Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), a method of screening for substance use disorders, represents one such evidenced-based practice that is reimbursable under many state Medicaid programs (see Box 1).8 Oregon is including an SBIRT benchmark and improvement target among the measures for which its ACO-like Medicaid Coordinated Care Organizations (CCOs) will be accountable. The CCOs will be eligible for incentive funds based on their performance on the SBIRT metric.9

Routine screening for common medical conditions among adults with behavioral health conditions is equally critical. Such screening can be accomplished by providing behavioral health practitioners with basic equipment like a scale, a blood pressure cuff, and a stethoscope, along with training in how to use them. The Small County Care Integration Quality Improvement Collaborative, established by the California Institute of Mental Health, takes this approach to assessing clients at the time of their intake at publicly funded behavioral health settings. County mental health centers participating in the Collaborative measure and record blood pressure, weight, and body mass index at each patient visit. When they identify a health concern, they refer patients for medical care as appropriate.

Screening for behavioral health problems is especially important as a prevention strategy for children and adolescents. According to the 2003 report from President George W. Bush’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, undetected and untreated “early childhood mental health disorders may persist and lead to a downward spiral of school failure, poor employment opportunities and poverty in adulthood.”10 Researchers have estimated that over 1 million children and adolescents experience problems suggestive of a pre-psychosis risk state.11 Early intervention may prevent the onset of psychosis among at-risk individuals, and also avert other adverse mental health outcomes associated with psychosis risk states, such as mood syndromes, substance use disorders, and functional decline.12 The earlier that depression is identified and treatment begins, the more effective the treatment is likely to be and the less likely recurrence becomes.

As with adults, physical health screens for children and adolescents with a behavioral health disorder or condition are as important as behavioral health screens for those who present for physical health reasons. For example, a child taking medication for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) may develop tachycardia and high blood pressure, and a child in active treatment for a behavioral health disorder may begin to experience symptoms of an emerging medical condition such as asthma. Routine medical screening by the principal behavioral health provider serves to foster identification of physical health conditions when they first appear and thereby prevent or mitigate their progression.

2. Navigators

Even when individuals with behavioral health problems get screened for other medical conditions and referred for care, obtaining the recommended follow-up services can be extremely challenging. People with serious behavioral health conditions often lack trust in professionals and agencies. Also, by the nature of their disorders, they may find the task of seeking medical care overwhelming or frightening. Further, people with chronic mental illness can be poor “historians” of their own health and unable to provide information that medical professionals need to diagnose their medical problems. For Medicaid beneficiaries and other low-income people with behavioral health conditions, these obstacles are compounded by poverty and other disadvantages. Recognizing the difficulties of navigating the health care system, professionals in both the physical and behavioral health spheres have affirmed the benefit of having an informed companion help patients with this challenge, and Medicaid programs are exploring opportunities to use a new cadre of “navigators” to serve in this role.

The navigator workforce in behavioral health settings includes professionals such as nurses and licensed clinical social workers as well as paraprofessionals. The role of navigators may be as simple as assisting individuals with behavioral health conditions in seeking medical help, or as sophisticated as directly interacting with medical professionals to advocate for a certain medical procedure or reconcile medications. Their role also involves promoting patient engagement to help achieve better-integrated, more holistic care. Whatever their formal credentials, effective navigators must have the ability to establish a trusting relationship with their clients. In addition, the relationships they establish with providers can foster a culture of coordination and integration between physical and behavioral health professionals. “Wellness Recovery Teams” offer an example of a clinical team-based navigator model that has improved access to and integration of primary care for patients with SMI (see Box 2).13 In another model, Medicaid programs in 30 states and the District of Columbia cover the services of “Certified Peer Specialists,”individuals who have personal experience with behavioral health needs and have completed training and certification to apply that experience to help their clients.14 Peer Specialists often interact with Medicaid beneficiaries outside of office-based settings, supporting them in their homes and communities. Evidence has shown that peer navigators are effective at improving “patient activation,” a construct that measures an individual’s self-management capacity, and at increasing the likelihood that a person with SMI will use primary care medical services.15

Box 2: Wellness Recovery Teams, piloted in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, represent a clinical team-based navigator model that includes Medicaid-funded navigators, a registered nurse (RN) with behavioral health training and experience, and a Master’s-prepared or licensed behavioral health professional. The Wellness Recovery Teams identify and engage with adults with SMI who also have at least one chronic medical condition. These navigator teams form a virtual multidisciplinary treatment team with each individual they serve by building relationships with professionals from all the agencies involved in their client’s care, including the PCP, medical specialists, social service providers, family members, Certified Peer Specialists, and other community-based service providers. Important functions of the RNs are to review clients’ medications and contact their PCPs to reconcile them if necessary, and to provide clinical insights and behavioral health consultation to the PCPs. The RNs also coach patients before their medical visits about what to expect and what kinds of information to share. Teaching clients self-advocacy and self-management is a priority.

In the first six months of the pilot, emergency department (ED) visits for medical care declined by 11% relative to the preceding six months, and psychiatric and medical inpatient admissions fell by 43% and 56%, respectively. All participating adults were connected with a PCP and 92% were connected to a medical specialist. Nearly 90% made progress toward recovery from substance abuse; 44% reported improved physical health. The pilot has produced other positive outcomes, too. Since working with the navigator teams, primary care practices have become more collaborative and willing partners in treating individuals with serious behavioral health disorders. ED physicians have also expressed strong support for the navigators, and at least one hospital developed a mental health rotation for its ED physicians following its experience with the teams.

3. Co-location

The physical distance between separate physical and behavioral health provider settings can itself pose a significant barrier to coordinated care. Especially for Medicaid beneficiaries and other low-income people, the child care and transportation costs associated with making trips to multiple locations can be prohibitive. Increasingly, an approach that is being used to address this problem is “co-location” – the provision of physical and behavioral health care at the same site.

The co-location trend is particularly visible in community health centers. In 2012, about 1,200 federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) operating in nearly 9,000 sites served more than 21 million patients in low-income communities; 41% of those served were Medicaid beneficiaries.16 The ACA established a dedicated five-year $11 billion trust fund for the health center program, primarily to increase health center capacity to meet expected increased demand for health care as coverage expands;17 this significant new investment has enabled many health centers to enhance the medical, oral, and behavioral health services they offer. The National Association of Community Health Centers’ (NACHC) reported that, in 2010, over 70% of health centers provided mental health services, 55% provided substance abuse treatment services, and 65% provided components of integrated care, such as a shared treatment plan.18 Health centers provide behavioral health services either by employing or contracting with licensed behavioral health practitioners, primarily to treat patients with mild to moderate behavioral health disorders. Some health centers provide a broader scope of behavioral health services and treat individuals with more serious and chronic mental health conditions. Golden Valley Health Centers in California is an example of a community health center that provides an array of behavioral health services to achieve integrated treatment for its patients (see Box 3).

Box 3: Golden Valley Health Centers, located in Merced and Stanislaus Counties, California, which serve a large number of Medicaid beneficiaries, have co-located behavioral and physical health services. They employ a psychologist, licensed clinical social workers, associate social workers, and psychiatrists to provide a full array of treatment for persons with SMI as well as milder depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and stress. The availability of physical and behavioral health services at the same site, an organizational culture of integration, and the use of an integrated care plan promote integrated care for Golden Valley patients with behavioral health conditions.

Changing the culture in provider settings is challenging and time-consuming. Clinicians in settings serving low-income populations and communities, in particular, face heavy caseloads and are stretched thin just to meet patients’ primary physical health care needs. Medical professionals may view initiatives that expand their work to encompass behavioral health issues as overwhelming, because identifying additional health needs and arranging for follow-up and referrals require more time and effort. The director of behavioral health services at Golden Valley reports that it took a few years for the medical staff, who ultimately did embrace integrated care, to recognize that the added time and effort up-front resulted in more effective and efficient care for their patients in the long run.

Medicaid’s system of prospective, cost-based payment for health centers supports the provision of behavioral health care in this setting because health centers can include the costs of licensed behavioral health practitioners in the calculation of their prospective rates. This integration of Medicaid funding for physical and behavioral services in the health center context contrasts with Medicaid fee-for-service payment, in which primary care and behavioral health providers are reimbursed separately for the specific services they deliver. Still, health centers may face other Medicaid payment barriers. For example, some states do not allow health centers to include the costs of multiple services provided to the same individual on the same day, such as a physical health and a behavioral health service. Other states prohibit same-day billing for certain combinations of behavioral health services.19 Also, although Medicaid covers the services and allows the costs of licensed behavioral health practitioners, many of the substance use treatment professionals employed by or under contract to health centers are not licensed; therefore, health centers must find other financing sources for these services. Finally, some states have not activated billing codes established specifically for Medicaid payment for SBIRT, hindering health centers from providing these particular services.

While co-location enables health centers to provide highly integrated care “within their walls,” this model has also been enhanced in some cases. For example, in Genesee County, Michigan, a pilot project involving a partnership between a health center and a community-based behavioral health provider located on the same campus has produced encouraging results (see Box 4).20 The pilot is a hybrid of co-location and navigator models that extends the reach of care integration by employing navigator teams to help clients gain access to specialty care and support services that are not available through either of the co-located entities.

Box 4: Genesee Health System health center and Hope Network. The Genesee Health System’s health center and Hope Network, a human services agency serving a predominantly Medicaid and low-income population, are located on a shared campus. Hope Network connects patients with PCPs in the health center, who share patient medical information and develop treatment plans collaboratively with Hope Network staff. The health center also provides pharmacy support, facilitating access to medication and educating patients about medication compliance. Hope Network employs Navigator Teams to monitor and support clients who are receiving primary care at the health center, locate needed specialty care that is not available through the health center, and connect patients with community-based services and supports. All needed services and supports are encompassed in a single integrated care plan that is coordinated by the Navigator Teams.

Hope Network reports that, for the small cohort of clients who received Navigator Team services and for whom longitudinal data were available, psychiatric inpatient admissions per person fell from an average of 1.95 in the year prior to receipt of navigator services, to .48 after receiving navigator services for one year.

4. Health Homes

“Health homes,” a new Medicaid state plan option established by the ACA, are designed to support comprehensive, coordinated care for Medicaid beneficiaries with complex health care needs. Medicaid health homes can be viewed as an outgrowth and enhancement of the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model, a care delivery approach designed to promote care that is patient-centered, coordinated across the health care spectrum, and provided by a team of professionals led by a patient’s personal physician.21 The ACA provides for a temporary 90% federal Medicaid matching rate for health home services provided to Medicaid beneficiaries who have two chronic conditions, or have one chronic condition and are at risk for another, or have one serious and persistent mental health condition.22 Health home services include comprehensive care management; care coordination and health promotion; comprehensive transitional care; patient and family support; referral to community and social support services; and the use of health information technology to support these services. The idea is that health home services connect, coordinate, and integrate the many services and supports, including primary health care, behavioral health care, acute and long-term services, and family and community-based services, that Medicaid beneficiaries with chronic and often complex conditions need.

In health home programs for Medicaid beneficiaries with serious mental health conditions, behavioral health agencies are a natural choice to be the designated health home providers. However, there are some challenges to overcome. First, behavioral health providers must be willing and able to provide the holistic and longitudinal care expected from the health home model, which may not have been their mode of practice previously. Second, state and federal laws intended to protect client confidentiality regarding the use of mental health and substance abuse treatment services have had the unintended consequence of preventing information-sharing that is essential to support integrated care for individuals with both physical and behavioral health needs. Third, both low Medicaid reimbursement rates for behavioral health services and fee-for-service payment have worked against a more integrated approach to care. In combination, these factors have contributed to a siloed system of behavioral health care, with limited incentives and capacity for coordination and collaboration aimed at producing more comprehensive and integrated care.

A growing number of states are using the health home option and its enhanced federal support to advance PH/BH integration for Medicaid beneficiaries. Missouri was the first state to adopt health homes specifically for individuals with SMI (see Box 5). Since then, four additional states (Rhode Island, Ohio, Iowa, and Maryland) have received approval for health home programs targeted to this population, and all but two of the 13 states with approved health home programs include SMI as one of the chronic conditions that can qualify Medicaid beneficiaries to enroll in health homes. The comprehensive nature of health home services and the holistic approach to care that health homes represent place health homes further “east” on the PH/BH integration continuum than the models discussed earlier.

Box 5: In Missouri’s health home program for people with behavioral health conditions, community mental health centers (CMHCs) certified by the state Department of Mental Health serve as designated providers, responsible for providing health home services as well as behavioral health treatment to participating Medicaid beneficiaries. In addition to meeting federal health home requirements, the CMHCs must also meet state-established criteria in order to provide health home services, including active use of the state’s electronic health record for care coordination and prescription monitoring; access standards; NCQA recognition as a PCMH; and improvement on state-specified clinical indicators.

Health home providers receive a per member per month fee that is based on the costs of establishing a clinical and administrative team to provide health home services, including a health home director responsible for leading practice transformation and day-to-day operation of the health home, and, at a minimum, nurse care managers with primary care backgrounds, primary care providers under contract to provide medical consultation and treatment, and administrative support staff. Since becoming designated health home providers, the CMHCs have provided extensive training to staff on topics such as patient engagement in treatment, support for patients with complex medical conditions, and team-based care. The CMHCs screen for medical concerns and use evidence-based practice guidelines to treat identified conditions, such as heart disease and diabetes. Additional strategies include comprehensive care management and care coordination, wellness education and self-care management, and integrated care plans, all of which are supported by the state’s electronic health record system for Medicaid enrollees.

Missouri has enrolled close to 19,000 Medicaid beneficiaries in CMHC-led health homes. Preliminary results reported by the state indicate that the percentage of beneficiaries in these health homes who had one hospitalization or more declined by 27% between 2011 and 2012. In addition, adults continuously enrolled since the inception of the program (approximately 2,800 individuals) showed marked improvement in key quality metrics related to management of diabetes, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels.23 These preliminary data suggest the potential that PH/BH integration through health homes might hold to improve outcomes, decrease unnecessary hospital utilization, and reduce costs for high-need Medicaid members.

5. System-Level Integration of Care

While the approaches described above involve efforts to coordinate physical and behavioral health care that sometimes extend well beyond the organizational boundaries of clinicians, practices, and agencies, each model stops short of fully integrated services and fiscal accountability, which underpin truly person-centered and holistic care. Such system-level or systemic integration represents the most advanced stage on the PH/BH integration continuum.

Box 6: In Maricopa County’s model, funding and accountability for care provided to county residents with SMI will rest with one managed care entity that is responsible for providing behavioral health care that encompasses recovery services for those with the most serious mental health and substance use disorders, and for providing physical as well as behavioral health services for Medicaid-covered adults with SMI. The managed care entity is expected to build on the use of SMI health homes, blending strengths of the PCMH model with best practices from the behavioral health system, including:

- Health education and health promotion;

- Primary prevention;

- Early identification and intervention that reduce the incidence and severity of serious physical and mental illness;

- Member-defined engagement, treatment planning, and service delivery;

- Peer and family members actively involved participants at all levels; and

- Implementation of SAMHSA evidence-based practices designed to promote and support Recovery for adults with SMI including Supported Employment, Permanent Supportive Housing and Assertive Community Treatment a multidisciplinary team approach that provides off-site treatment, rehabilitation and support to persons with serious and persistent mental illness.

Additionally, the managed care plan would have to meet specific benchmarks designed to measure the plan’s performance in improving care and the patient care experience and in reducing growth in aggregate physical and behavioral health care costs.

One model of system-level integration can be seen in the Medicaid managed care program in Maricopa County, Arizona (see Box 6). Many states with Medicaid managed care programs include limited behavioral health benefits in their contracts with managed care organizations (MCOs) – typically, a limited psychiatric inpatient benefit, outpatient therapy and, sometimes, inpatient detoxification. Behavioral health services for Medicaid enrollees who require more intensive treatment and rehabilitation services and supports have often been viewed as beyond the scope of Medicaid MCO contracts, and beneficiaries generally obtain these services on a fee-for-service basis, or through a separate Behavioral Health Organization (BHO), or through the local or state mental health and substance abuse authorities. In a departure from this model, Arizona recently issued a procurement for a contractor to serve as the Regional Behavioral Health Authority in Maricopa County, which would be responsible for providing all Medicaid and other publicly-funded behavioral health services for county residents and, in the case of adult Medicaid beneficiaries with SMI, for providing Medicaid-covered physical health services as well. In this way, Arizona is seeking a comprehensive, fully integrated health plan to provide the full complement of physical and behavioral health care for adult Medicaid enrollees with SMI, including coordination of Medicare and Medicaid benefits for dual eligible members. In addition to integrated PH/BH care for adults with SMI, the chosen vendor will also be responsible for behavioral health services for both children and other adults in Medicaid, and for non-Medicaid children and adults for whom the Arizona Department of Health Services’ Division of Behavioral Health Services receives funding. The state recently issued a Request for Information (RFI) exploring the feasibility of implementing a similar model statewide. An assessment of whether the approach – that is, holding a managed care entity accountable and at financial risk for the full spectrum of behavioral health and Medicaid-covered physical health services for the Medicaid SMI population – results in a high degree of PH/BH integration will be of wide interest to other state Medicaid programs. It may also help to inform federal initiatives to promote innovative models of coordinated and accountable care that are focused particularly on individuals and populations with the most complex and high-cost needs for care.

Conclusion

The rising human as well as economic costs of fragmented health care, especially for those with the most complex needs, have fueled interest in and demand for more patient-centered approaches to providing care to Medicaid beneficiaries. Because of the morbidity and mortality risk profile of those with behavioral health conditions, Medicaid’s large role in covering this population, and the fact that individuals with behavioral health comorbidities are among the program’s highest-cost beneficiaries, models that improve the integration of physical and behavioral health care are attracting keen attention and taking hold in many places. No single approach in Medicaid is likely to be a universal solution; rather, a diversity of promising strategies present options for states, health plans, and providers seeking to move further in the direction of integrating care. As different models emerge and evolve, it will be important to examine how they operate and what they require, and to evaluate their performance from the perspective of patient outcomes and experience and other Medicaid program goals.

This brief was prepared by Mike Nardone and Sherry Snyder of Health Management Associates and Julia Paradise of the Kaiser Family Foundation.